- Home

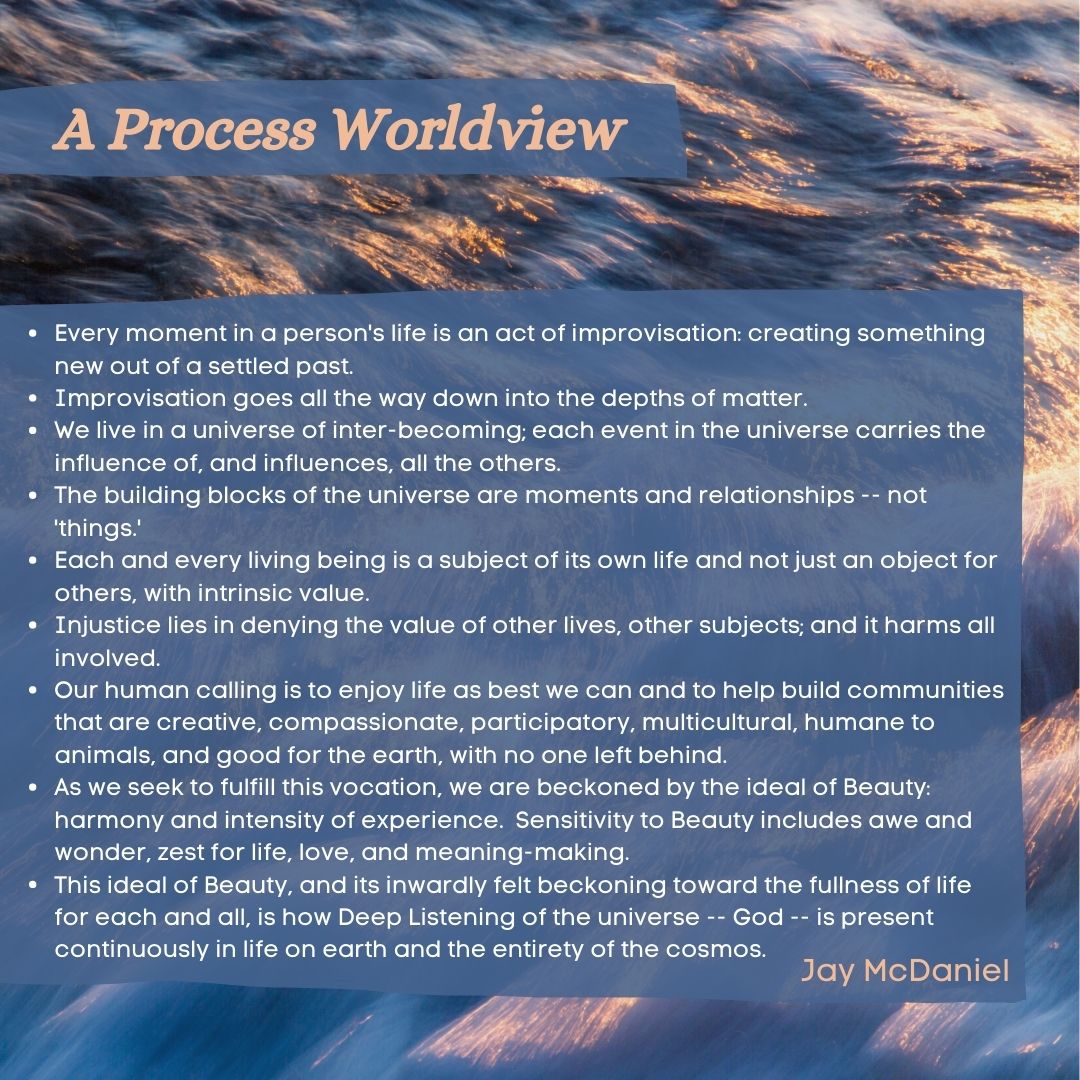

- Process Worldview

- Community

- Art and Music

- Whitehead and Process Thinking

- Podcasts

- Spirituality

- Ecological Civilization

- Education

- Contact

- Social Justice

- Science

- Animals

- Sacred Poems

- Whitehead Videos

- Index of All Titles

- Practicing Process Thought

- Process Spirituality: A Spiritual Alphabet

- Recent Posts

Music

|

|

|

The Task of the Artist in a Time of Monsters

We come to know monsters early in our lives. Our childhoods are filled with scary things that “go bump” in the night. A ferocious fire-breathing creature with bulging eyes, fangs, and foaming at the mouth stands over us. We pull the covers over our head; pray and pretend that the monster is just a figment of our imagination.

Monsters are real. History is peopled with millions of corpses left in their wake. Monsters—indeed—are not rare. We rattle off monsters’ names with great ease and compare them to our present brutes. Monsters carry out individual atrocities and conceal our complicity, which is far more sinister than the monsters themselves. Not only do we hide from monsters, we hide behind them. Nations have always bred monsters; and nations love monsters but not artists. Artists know that all nations are morally bankrupt and that politics are diseased. They remind nations that monsters are not new.

Albert Camus pleaded with the artist to never side with the makers of history but rather the victims of it. And the victims will be legion —Muslim, Black, queer, young, undocumented, old, female, differently-abled, and all of the poor. Artists must be lobbyists for the languishing. While monsters spew vile words, artists do not take any delight in such talk because demonization cannot defeat demagoguery. Audre Lorde taught that using the master’s tools makes us the master’s tools. Artists do not shame those living in the night; artists shine light.

James Baldwin—the greatest amongst us—called artists to quarrel with their nations as lovers do. Artists are not politicians. They are legislators of hope, parliamentarians of possibility. To be sure, the past is a guide, but melancholy can be a nation’s undoing. Nostalgia is a form of mourning for a past that never was, because the present is unbearable and the future is unforeseeable. When the present obscures the future and undermines the past, artists are diplomats between the world that was, the world that is and the world that is to be. So then artists’ allegiances can never be to a flag, a party, or a state. Love is their government.

When monsters say that we should lie down and die, the art of loving and living is the sacred task of artists—making home from rubble held together by the very thing that monsters have sought to snuff out for ages—joy. Artists are architects of being; building communities where there are no strangers only neighbors. And monsters fear that.

-Rev. Osagyefo Uhuru Sekou

Monsters are real. History is peopled with millions of corpses left in their wake. Monsters—indeed—are not rare. We rattle off monsters’ names with great ease and compare them to our present brutes. Monsters carry out individual atrocities and conceal our complicity, which is far more sinister than the monsters themselves. Not only do we hide from monsters, we hide behind them. Nations have always bred monsters; and nations love monsters but not artists. Artists know that all nations are morally bankrupt and that politics are diseased. They remind nations that monsters are not new.

Albert Camus pleaded with the artist to never side with the makers of history but rather the victims of it. And the victims will be legion —Muslim, Black, queer, young, undocumented, old, female, differently-abled, and all of the poor. Artists must be lobbyists for the languishing. While monsters spew vile words, artists do not take any delight in such talk because demonization cannot defeat demagoguery. Audre Lorde taught that using the master’s tools makes us the master’s tools. Artists do not shame those living in the night; artists shine light.

James Baldwin—the greatest amongst us—called artists to quarrel with their nations as lovers do. Artists are not politicians. They are legislators of hope, parliamentarians of possibility. To be sure, the past is a guide, but melancholy can be a nation’s undoing. Nostalgia is a form of mourning for a past that never was, because the present is unbearable and the future is unforeseeable. When the present obscures the future and undermines the past, artists are diplomats between the world that was, the world that is and the world that is to be. So then artists’ allegiances can never be to a flag, a party, or a state. Love is their government.

When monsters say that we should lie down and die, the art of loving and living is the sacred task of artists—making home from rubble held together by the very thing that monsters have sought to snuff out for ages—joy. Artists are architects of being; building communities where there are no strangers only neighbors. And monsters fear that.

-Rev. Osagyefo Uhuru Sekou

The Artist as a Four Hopes Provocateur

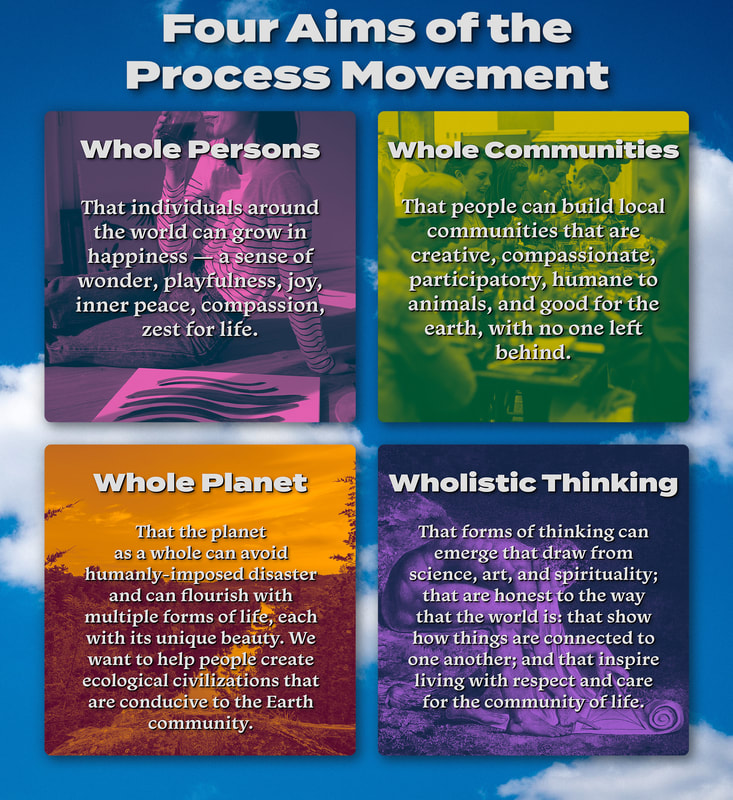

A Four Hopes Provocateur creates and evokes lures for the four hopes of process thought: whole persons, whole communities, a whole planet, and wholistic thinking. "Lures" are proposals or, in Whitehead's austere language, "propositions" for how we might look at the world, hear the poignancy, beauty, and pain of people and other living beings, and act in ways what help bring about beloved community. The music of Reverend Sekou offers these kinds of lures.

This is not because Rev, Sekou identifies himself as a process theologian, although many of his ideas as expressed in his essays resonate with what other process theologians say and think. It is because his music inspires us to think creatively about so many things that are important to us: the improvisational character of life, the intrinsic value of each person, the role that music can play in evoking 'process' sensibilities, the ways in which many different influences can shape our lives, and, of course, the importance of creating and sustaining whole or compassionate communities. Truth be told, the themes that emerge in the sounds, melodies, lyrics, and rhythms of his music are what we in the process family want to be about. And his music, no less than his essays, are examples of what we mean by "wholistic thinking" or, in his case, "wholistic theology." The purpose of this page is to thank him for his work.

This is not because Rev, Sekou identifies himself as a process theologian, although many of his ideas as expressed in his essays resonate with what other process theologians say and think. It is because his music inspires us to think creatively about so many things that are important to us: the improvisational character of life, the intrinsic value of each person, the role that music can play in evoking 'process' sensibilities, the ways in which many different influences can shape our lives, and, of course, the importance of creating and sustaining whole or compassionate communities. Truth be told, the themes that emerge in the sounds, melodies, lyrics, and rhythms of his music are what we in the process family want to be about. And his music, no less than his essays, are examples of what we mean by "wholistic thinking" or, in his case, "wholistic theology." The purpose of this page is to thank him for his work.

If you are unfamiliar with the process movement, see the images below. They give you a sense of how we look at the world and what we think important. See also the Process Nexus or the Center for Process Studies or the Cobb Institute for Process and Practice or Process and Faith.

Interview

On Spotify

|

|

|

Reverend Osagyefo Sekou

featured in Newsounds

The Reverend Osagyefo Sekou draws from a deep well of American music on his new album, called In Times Like These. Blues and gospel traditions, but specifically also "North Mississippi Hill Country Music, Arkansas Delta Blues, 1960s Rock and Roll, Memphis Soul, Chuck Berry St Louis vibes, and Pentecostal steel guitar." Now if you’re thinking that those are musical holdovers from another time, the activist, author, documentary filmmaker and theologian Reverend Sekou wants you to know that that music has become powerful and relevant again, in times like these. The album features Luther and Cody Dickinson of the North Mississippi All-Stars, and Rev Sekou toured with them back in 2017. He and The Sealbreakers play some of the tunes, in-studio. (Archives, 2017.)

About Rev. Sekou

from the biography on Rev. Sekou's website:

Rev. Osagyefo Uhuru Sekou

Osagyefo (oh-sah-GEE-fo) Uhuru (ooh-WHO-roo) Sekou (SAY-koo)

It sounds so simple when noted activist, theologian, author, documentary filmmaker, and blues/soul/gospel musician Reverend Osagyefo Sekou says it but it belies the incredible power and thoughtfulness of his work. “Wherever people are catching hell, I try and show up,” he says of his work, which spans from concerts worldwide to in-person organizing in troubled places from Charlottesville, VA to Beirut, Lebanon; New Orleans, LA after Katrina to Ferguson, MO after the death of Michael Brown, Jr.

With the Deep Abiding Love Project, he has helped trained over ten thousand clergy and activists in militant nonviolent civil disobedience through the United States. Rev. Sekou was selected by Ebony Magazine’s Power 100, NAACP History Makers (2015), and on the Yerba Buena Center for the Arts 100 –list of creative thinkers.

The musician and pastor explains the source of his commitment, saying, “My understanding of faith requires justice doing and making in the world. Anything less is idolatry.” Based in Seattle, Rev. Sekou pastors a church there in addition to his other work.

His music is a chief tool of this work. NPR’s Bob Boilen testified that Rev. Sekou delivered one of “the most rousing Tiny Desk performances.”

“When people see me in concert, I pray they come away a little freer,” he attests. Born in St. Louis, Missouri and raised in the rural Arkansas delta, he grew up steeped in a unique combination of Arkansas delta blues, Memphis soul, 1970s funk, and gospel that shines through his own music with his Nashville-based band the Freedom Fighters. He remembers, “I was a choir boy who hung out in gambling houses with my uncle. I grew up hearing the blues, soul, funk, and gospel. So my music lives in that liminal space in between sacred and secular.” His live concerts are often likened to gospel revivals and it’s not uncommon to see audiences moved to tears and moved to dance at the same time.

Sekou’s debut album "In Times Like These” was produced by the six-time Grammy nominated group North Mississippi Allstars. AFROPUNK heralded its “deep bone-marrow-level conviction.” The single, “We Comin'” was named the new anthem for the modern Civil Rights movement by the St. Louis Post-Dispatch.

On July 6, 2018, over 1,500 people gathered at the historic Levitt Shell in Memphis, TN to welcome Rev. Sekou home to the mid-south (Memphis, TN being the nearest metropolitan area to the Arkansas delta). For nearly two hours, the audience was treated to stellar performance that was one-part protest rally, one-part Pentecostal tent revival, and one-part late night juke joint. Sekou performed both new arrangements from his albums and never-released music. The revelatory concert, with his band the Freedom Fighters, became the live album, “When We Fight, We Win,” which prompted Paste Magazine to say, "Rev. Sekou delivers the spiritual performance we need now." ...more

Rev. Osagyefo Uhuru Sekou

Osagyefo (oh-sah-GEE-fo) Uhuru (ooh-WHO-roo) Sekou (SAY-koo)

It sounds so simple when noted activist, theologian, author, documentary filmmaker, and blues/soul/gospel musician Reverend Osagyefo Sekou says it but it belies the incredible power and thoughtfulness of his work. “Wherever people are catching hell, I try and show up,” he says of his work, which spans from concerts worldwide to in-person organizing in troubled places from Charlottesville, VA to Beirut, Lebanon; New Orleans, LA after Katrina to Ferguson, MO after the death of Michael Brown, Jr.

With the Deep Abiding Love Project, he has helped trained over ten thousand clergy and activists in militant nonviolent civil disobedience through the United States. Rev. Sekou was selected by Ebony Magazine’s Power 100, NAACP History Makers (2015), and on the Yerba Buena Center for the Arts 100 –list of creative thinkers.

The musician and pastor explains the source of his commitment, saying, “My understanding of faith requires justice doing and making in the world. Anything less is idolatry.” Based in Seattle, Rev. Sekou pastors a church there in addition to his other work.

His music is a chief tool of this work. NPR’s Bob Boilen testified that Rev. Sekou delivered one of “the most rousing Tiny Desk performances.”

“When people see me in concert, I pray they come away a little freer,” he attests. Born in St. Louis, Missouri and raised in the rural Arkansas delta, he grew up steeped in a unique combination of Arkansas delta blues, Memphis soul, 1970s funk, and gospel that shines through his own music with his Nashville-based band the Freedom Fighters. He remembers, “I was a choir boy who hung out in gambling houses with my uncle. I grew up hearing the blues, soul, funk, and gospel. So my music lives in that liminal space in between sacred and secular.” His live concerts are often likened to gospel revivals and it’s not uncommon to see audiences moved to tears and moved to dance at the same time.

Sekou’s debut album "In Times Like These” was produced by the six-time Grammy nominated group North Mississippi Allstars. AFROPUNK heralded its “deep bone-marrow-level conviction.” The single, “We Comin'” was named the new anthem for the modern Civil Rights movement by the St. Louis Post-Dispatch.

On July 6, 2018, over 1,500 people gathered at the historic Levitt Shell in Memphis, TN to welcome Rev. Sekou home to the mid-south (Memphis, TN being the nearest metropolitan area to the Arkansas delta). For nearly two hours, the audience was treated to stellar performance that was one-part protest rally, one-part Pentecostal tent revival, and one-part late night juke joint. Sekou performed both new arrangements from his albums and never-released music. The revelatory concert, with his band the Freedom Fighters, became the live album, “When We Fight, We Win,” which prompted Paste Magazine to say, "Rev. Sekou delivers the spiritual performance we need now." ...more