- Home

- Process Worldview

- Community

- Art and Music

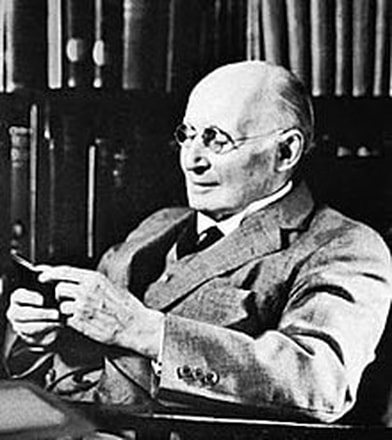

- Whitehead and Process Thinking

- Podcasts

- Spirituality

- Ecological Civilization

- Education

- Contact

- Social Justice

- Science

- Animals

- Sacred Poems

- Whitehead Videos

- Index of All Titles

- Practicing Process Thought

- Process Spirituality: A Spiritual Alphabet

- Recent Posts

Some Crazy Ideas *

- The whole universe is alive with feeling and connection: a seamless web of inter-becoming.

- The building blocks of the universe aren't solid things but rather momentary events.

- Even physical objects -- sticks and stones, tables and chairs -- are made of these events.

- Every event has mind-like properties such as feeling and emotion, enjoyment and creativity.

- Nature is alive through and through. Energy is a form of feeling. Inert or dead matter is an illusion.

- Feelings aren't just private; they are modes of connection.

- Every event is unique, with a life of its own. It is an actual entity. It is the subject of its life.

- The subject of a momentary event is not separate from its experience; it is its act of experiencing.

- How it experiences is what it becomes.

- The act of experiencing is a concrescence -- a unification and making concrete -- of the universe.

- Once the act is complete, something new is added to the universe: "the many become one. and are increased by one."

- The souls or psyches of human beings (and other animals) are acts of concrescence, too.

- We humans are not skin-encapsulated egos but rather relational selves.

- We are slightly new selves at every moment.

- We become ourselves through, not apart from, our felt connections with others.

- As we are affected by the world outside us, it becomes part of us: "The world is my body."

- The world is God's body, too. God is the embodied mind of the universe.

- God is love: a fellow sufferer who understands, feeling the feelings of all living beings in an empathic way.

- God is the poet of the universe, continuously acting through evocation not coercion.

- God's dream for us is that we live with respect and care for the entire community of life, humans much included.

- God's dream is also that we have fun along the way; the very purpose of life is to enjoy it.

- God needs us to help the dream come true.

- We need God to help the dream come true.

- Trust the moonlight (the influx of new ideas).

* That is, crazy ideas espoused by Whitehead. Whitehead had many crazy ideas; 1,632 of them by my count. Sometimes he organized them in a systematic way, as in his book Process and Reality: An Essay in Cosmology. Sometimes he just shared them in conversation. These are but a few of them. Process philosophers believe that if we thought of the world and ourselves in these ways, we would live more lightly on the earth and gently with others. They recognize that many other philosophical and cultural traditions also espouse these ideas. The ideas are instances of 'organic' thinking. (Jay McDaniel)

angel headed hipsters

at the end of modernity

The world needs more madness. Lots more. Of course there are two kinds of madness: constructive and destructive. The world needs more constructive madness and less destructive madness. Let's speak of the destructive kind as insanity.

Conventional society is insane in its worship of power, violence, vengeance, and money. It is insane in its spewing of toxins into the atmosphere and waters. It is insane in its acceptance of horrifying gaps between rich and poor. It is insane in its acceptance of global rape culture and global war culture. It is insane in its hardness of heart and mind, as expressed in fundamentalisms both religious and secular. It is insane in the way it forces some people to suppress quiet and beautifully different ways of thinking and feeling, in the interests of conforming to a single model of the fully human. It is insane in not knowing it is insane.

And yet, when people criticize these insanities they are called mad. Or at least out of touch with reality. The truth is, they are not out of touch with reality. Conventional society is out of touch with the better angels of the human spirit. These prophets sense higher possibilities.

The Madness of Jesus

Remember Jesus? Remember how, according to some people, he was speaking for God in hoping for a kingdom of love which will come on earth as it is in heaven? And remember how he hung around with all the people establishment-types didn't want to hang around: lepers, prostitutes, tax collectors, women. Remember how crazy he was: telling people to turn the other cheek even when struck and to give people another piece of clothing even after their first piece of clothing had been stolen. Remember how he let women put ointment on his feet and kiss them when some said he ought to be a bit more formal. Remember how he washed other people's feet, too?

Was he bad? Of course he was bad, at least by conventional standards of morality. Was he mad? Of course he was. He was madly in love with a possibility that had not yet been realized and madly intolerant of violence and greed. Was he speaking for God? Of course he was. At least this is what we process thinkers believe. We believe that God often speaks through the mouths of people who contravene conventional morality in light of a better hope.

Take a look at John Cobb's Five Foundations for a New Civilization, where the fifth foundation lies in transcending conventional morality. As John Cobb suggests, you can't follow God without being a little mad.

The Power of Poets

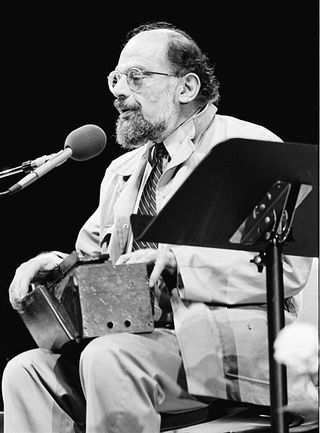

Who does this today? Sometimes, in our time, it is the poets who do this. I'll take one example: Allen Ginsberg.

Listen to him read "Howl" in the video above. Allen Ginsberg wanted to make the world safe for angel-headed hipsters who burn for ancient heavenly connections to the starry dynamo in the machinery of night. He had seen the best minds of his generation destroyed by madness: staring, hysterical, and naked, looking for a fix. They would pass through the halls of academia with radiant cool eyes, hallucinating Arkansas, filled with a sense of Blake-light tragedy among the scholars of war. They were trapped in a merciless society, a global rape culture, a society obsessed with guns and frightened by intimacy. Their response was to stay up all night, talking about jazz, talking about Poe and Plotinus and St. John of the Cross, burning cigarette holes in their arms, protesting the narcotic tobacco haze of capitalism.

Please forgive me. Many of the lines above come from Ginsberg's famous poem Howl. If only I could write and speak so hallucinogenically.

Was Ginsberg mad? Yes he was. He was mad for heavenly connections, intoxicated with the hope that people of different cultures can live together without harming each other: free from greed, free from fear, free for intimacy.

Ginsberg knew both kinds of madness: the constructive and the destructive. In Howl we hear a protest against destructive madness and a celebration of constructive.

Constructive madness is gentle and playful, tragic and hopeful. And so often, like Ginsberg, it is exploring new ideas, shocking familiar sensibilities along the way.

In Process and Reality Whitehead writes: "Each new epoch enters upon its career by waging unrelenting war upon the aesthetic gods of its immediate predecessor." (p. 340).

Ginsberg is waging war against the aesthetic gods of predictability and familiarity. He is beckoned by new and hopeful dreams. A dream that the senses can be welcomed rather than feared, that the body can be reclaimed as a site of holy delight.

All new dreams are mad when they are first spoken. They disrupt traditional ways of thinking. They transgress traditional sensibilities. They find flowers in the garbage, sacredness in the squalor.

Ginsberg, with his Jewish roots, was in this messianic tradition, as was Jesus. He followed his inner moonlight and shared his madness. Don't you miss him? I do, too.

God is Moonlight

For my part, I heard Ginsberg give poetry readings three times in my life: once when I was in college, once in graduate school, and once at the school where I teach in Arkansas.

He visited a class I was teaching. He talked about the importance of living truthfully, in obedience to the calling of the Calling.

He didn't use the word Calling. It's a Whiteheadian word. But he was Jewish and I think he would understand what I mean. I'm talking about initial aims, those fresh possibilities that emerge in our hearts and imaginations, and that beckon us, moment by moment, when we follow the inner moonlight. Initial aims are inner moonlight. In Whitehead's philosophy these aims come from God.

These moonlight aims are within us yet more than us. We cannot cup them in our hands but we can cup them in our hearts, allowing them to help us become our better and more angelic selves: angel-headed hipsters.

I could feel these aims when Allen Ginsberg spoke in my class. There was a moonlight in his eyes. He was driven by novelty and honesty, love and wonder, jazz and justice. He refused to be embalmed by order, mental or physical.

Patricia Adams Farmer talks about how the jazz musician, Dave Brubeck, invited us to think in fresh ways, in 5/4 time rather than 4/4 time. She begins her article with a famous quote from Whitehead:

The art of progress is to preserve order

amid change, and to preserve change amid

order. Life refuses to be embalmed alive.

I think Ginsberg might have liked the second part of this quote. Ginsberg's life was a protest against being embalmed alive.

Queer Time

I don't know what time signature he played in. Maybe sometimes it was 5/4 and sometimes 86/2 and periodically 11/3. I think he shifted time all the time. He couldn't be circled. He was at home in queer time. This is another Whiteheadian idea. Subjectively time isn't all that linear. Objectively it may flow in a unidirectional way; once things perish there's something about them that can't come back. Even Allen can't come back. But subjectively time is flowing in every direction, as memory and anticipation, hoping and recollecting, coalesce and concresce, differently at every moment. Always there are different rhythms. Allen Ginsberg was at home in them.

The End of Modernity

The day when he spoke to my class, I had lunch with him afterwards. He was just as I hoped he would be: kind, crazy, Jewish, Buddhist, scary, loving, wild-eyed, soft-hearted, funny, and serious. Modernity at its very best!

In the audio talk below,, Robert Pinsky links Allen Ginsberg with other modernist poets: T.S. Eliot and Ezra Pound and William Carlos Williams. Pinsky says Ginsberg was as modernist in his way, as were Eliot and Pound and Williams in theirs.

Conventional society is insane in its worship of power, violence, vengeance, and money. It is insane in its spewing of toxins into the atmosphere and waters. It is insane in its acceptance of horrifying gaps between rich and poor. It is insane in its acceptance of global rape culture and global war culture. It is insane in its hardness of heart and mind, as expressed in fundamentalisms both religious and secular. It is insane in the way it forces some people to suppress quiet and beautifully different ways of thinking and feeling, in the interests of conforming to a single model of the fully human. It is insane in not knowing it is insane.

And yet, when people criticize these insanities they are called mad. Or at least out of touch with reality. The truth is, they are not out of touch with reality. Conventional society is out of touch with the better angels of the human spirit. These prophets sense higher possibilities.

The Madness of Jesus

Remember Jesus? Remember how, according to some people, he was speaking for God in hoping for a kingdom of love which will come on earth as it is in heaven? And remember how he hung around with all the people establishment-types didn't want to hang around: lepers, prostitutes, tax collectors, women. Remember how crazy he was: telling people to turn the other cheek even when struck and to give people another piece of clothing even after their first piece of clothing had been stolen. Remember how he let women put ointment on his feet and kiss them when some said he ought to be a bit more formal. Remember how he washed other people's feet, too?

Was he bad? Of course he was bad, at least by conventional standards of morality. Was he mad? Of course he was. He was madly in love with a possibility that had not yet been realized and madly intolerant of violence and greed. Was he speaking for God? Of course he was. At least this is what we process thinkers believe. We believe that God often speaks through the mouths of people who contravene conventional morality in light of a better hope.

Take a look at John Cobb's Five Foundations for a New Civilization, where the fifth foundation lies in transcending conventional morality. As John Cobb suggests, you can't follow God without being a little mad.

The Power of Poets

Who does this today? Sometimes, in our time, it is the poets who do this. I'll take one example: Allen Ginsberg.

Listen to him read "Howl" in the video above. Allen Ginsberg wanted to make the world safe for angel-headed hipsters who burn for ancient heavenly connections to the starry dynamo in the machinery of night. He had seen the best minds of his generation destroyed by madness: staring, hysterical, and naked, looking for a fix. They would pass through the halls of academia with radiant cool eyes, hallucinating Arkansas, filled with a sense of Blake-light tragedy among the scholars of war. They were trapped in a merciless society, a global rape culture, a society obsessed with guns and frightened by intimacy. Their response was to stay up all night, talking about jazz, talking about Poe and Plotinus and St. John of the Cross, burning cigarette holes in their arms, protesting the narcotic tobacco haze of capitalism.

Please forgive me. Many of the lines above come from Ginsberg's famous poem Howl. If only I could write and speak so hallucinogenically.

Was Ginsberg mad? Yes he was. He was mad for heavenly connections, intoxicated with the hope that people of different cultures can live together without harming each other: free from greed, free from fear, free for intimacy.

Ginsberg knew both kinds of madness: the constructive and the destructive. In Howl we hear a protest against destructive madness and a celebration of constructive.

Constructive madness is gentle and playful, tragic and hopeful. And so often, like Ginsberg, it is exploring new ideas, shocking familiar sensibilities along the way.

In Process and Reality Whitehead writes: "Each new epoch enters upon its career by waging unrelenting war upon the aesthetic gods of its immediate predecessor." (p. 340).

Ginsberg is waging war against the aesthetic gods of predictability and familiarity. He is beckoned by new and hopeful dreams. A dream that the senses can be welcomed rather than feared, that the body can be reclaimed as a site of holy delight.

All new dreams are mad when they are first spoken. They disrupt traditional ways of thinking. They transgress traditional sensibilities. They find flowers in the garbage, sacredness in the squalor.

Ginsberg, with his Jewish roots, was in this messianic tradition, as was Jesus. He followed his inner moonlight and shared his madness. Don't you miss him? I do, too.

God is Moonlight

For my part, I heard Ginsberg give poetry readings three times in my life: once when I was in college, once in graduate school, and once at the school where I teach in Arkansas.

He visited a class I was teaching. He talked about the importance of living truthfully, in obedience to the calling of the Calling.

He didn't use the word Calling. It's a Whiteheadian word. But he was Jewish and I think he would understand what I mean. I'm talking about initial aims, those fresh possibilities that emerge in our hearts and imaginations, and that beckon us, moment by moment, when we follow the inner moonlight. Initial aims are inner moonlight. In Whitehead's philosophy these aims come from God.

These moonlight aims are within us yet more than us. We cannot cup them in our hands but we can cup them in our hearts, allowing them to help us become our better and more angelic selves: angel-headed hipsters.

I could feel these aims when Allen Ginsberg spoke in my class. There was a moonlight in his eyes. He was driven by novelty and honesty, love and wonder, jazz and justice. He refused to be embalmed by order, mental or physical.

Patricia Adams Farmer talks about how the jazz musician, Dave Brubeck, invited us to think in fresh ways, in 5/4 time rather than 4/4 time. She begins her article with a famous quote from Whitehead:

The art of progress is to preserve order

amid change, and to preserve change amid

order. Life refuses to be embalmed alive.

I think Ginsberg might have liked the second part of this quote. Ginsberg's life was a protest against being embalmed alive.

Queer Time

I don't know what time signature he played in. Maybe sometimes it was 5/4 and sometimes 86/2 and periodically 11/3. I think he shifted time all the time. He couldn't be circled. He was at home in queer time. This is another Whiteheadian idea. Subjectively time isn't all that linear. Objectively it may flow in a unidirectional way; once things perish there's something about them that can't come back. Even Allen can't come back. But subjectively time is flowing in every direction, as memory and anticipation, hoping and recollecting, coalesce and concresce, differently at every moment. Always there are different rhythms. Allen Ginsberg was at home in them.

The End of Modernity

The day when he spoke to my class, I had lunch with him afterwards. He was just as I hoped he would be: kind, crazy, Jewish, Buddhist, scary, loving, wild-eyed, soft-hearted, funny, and serious. Modernity at its very best!

In the audio talk below,, Robert Pinsky links Allen Ginsberg with other modernist poets: T.S. Eliot and Ezra Pound and William Carlos Williams. Pinsky says Ginsberg was as modernist in his way, as were Eliot and Pound and Williams in theirs.

Pinsky's talk is on Modernity and Memory. I think it is one of the best talks on modern poetry you can hear. It's offered by the Poetry Foundation.

Here are five points he makes:

1. Poetry has music as its source and inspiration. It is bodily and rhythmic. Implicitly you'll want to dance when you hear it.

2. Our need today is to consult our ancestors without worshiping them. If we worship our ancestors we make gods of them. The better option is to let them live as friends and guides.

3. Modernism remembers differently from previous forms of poetry. "Poetry for a long time praised the ruling order; it celebrated and praised the majority religion." Modernist poetry praises the fragmented and un-elevated. It doesn't hide from the sacred in the squalor.

4. Remembering is always a form of forgetting. As Whitehead would put it, when we remember the past we select out certain aspects of it and, at that very moment, neglect others. We remember by forgetting.

5. Modernism is a form of memory that wants to disrupt complacency. It is a quest for novelty.

We live in a new age. Modernism is over. But we best remember modernism by preserving its impulse toward novelty. There's a lovely side to modernity. Follow your inner moonlight - don't hide the madness. Don't let harmony become sameness.

Don't you miss Allen Ginsberg? And maybe even Whitehead? I do, too.

-- Jay McDaniel

Pinsky's talk is on Modernity and Memory. I think it is one of the best talks on modern poetry you can hear. It's offered by the Poetry Foundation.

Here are five points he makes:

1. Poetry has music as its source and inspiration. It is bodily and rhythmic. Implicitly you'll want to dance when you hear it.

2. Our need today is to consult our ancestors without worshiping them. If we worship our ancestors we make gods of them. The better option is to let them live as friends and guides.

3. Modernism remembers differently from previous forms of poetry. "Poetry for a long time praised the ruling order; it celebrated and praised the majority religion." Modernist poetry praises the fragmented and un-elevated. It doesn't hide from the sacred in the squalor.

4. Remembering is always a form of forgetting. As Whitehead would put it, when we remember the past we select out certain aspects of it and, at that very moment, neglect others. We remember by forgetting.

5. Modernism is a form of memory that wants to disrupt complacency. It is a quest for novelty.

We live in a new age. Modernism is over. But we best remember modernism by preserving its impulse toward novelty. There's a lovely side to modernity. Follow your inner moonlight - don't hide the madness. Don't let harmony become sameness.

Don't you miss Allen Ginsberg? And maybe even Whitehead? I do, too.

-- Jay McDaniel