GYOBUTSUJI AND THE ENVIRONMENT:

PRACTICING WITH ALL BEINGS

BY SHORYU BRADLEY

October 15, 2015

originally posted in Ancient Way Journal:

A Journal of Tradititional Soto Zen Practice

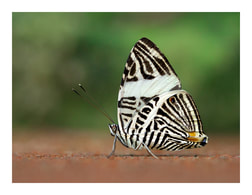

Images from Gyobutsuji |

A few years ago a person who had visited Gyobutsuji’s website asked me how I got the idea to establish a “green” monastery. The questions surprised me a bit because I had not previously considered being “green” a particularly notable feature of Gyobutsuji, although allowing the monastery to be as environmentally conscientious as possible has indeed been one of my primary aspirations. But it had not really occurred to me that a contemporary Zen monastery would be anything other than sensitive to its impact on our delicate Earth. Caring for all things we encounter, most definitely including the natural environment that sustains us, to my mind is essential to today’s Zen teaching and practice. In the essay that follows I’ll present some of the reasons I feel this is so and relate them to the practice here at Gyobutsuji.

The Monastery’s Name Perhaps a good way to begin presenting these reasons is to take a look at the origins of Gyobutsuji’s name. It was inspired by the chapter of Dogen Zenji’s Shobogenzo (True Dharma Eye Treasury) entitled Gyobutsu Igi (Dignified Conduct of Practice Buddha).Gyobutsu igi is a Buddhist term usually referring to the deportment and practice of a buddha. As a Buddhist one endeavors to emulate this activity of the great awakened beings. But in a twist typical of his literary genius, Dogen opens the phrase up to a deeper meaning: All buddhas without exception fully practice dignified conduct:this [practice] is Practice Buddha. […] Sharing one corner of the Buddha’s dignified conduct is done together with the entire universe, the great earth, and with the entire coming-and-going of life-and-death. […] This is nothing other than the dignified conduct of the oneness of Practice and Buddha.1 Here “Buddha” of course doesn’t refer to any particular person or thing; it is beyond any boundaries. Elsewhere in his ShobogenzoDogen referred to this boundary-less reality as Zenki, or “Total Dynamic Function;” perhaps we could simply call it “life” in the broadest sense of the word. At Gyobutsuji we endeavor to express this teaching and reality in practice, so we consider our practice as an expression of “truth” realized with the entirety of life. InGyobutsu Igi Dogen Zenji presents genuine practice as the universal buddha he called “Practice Buddha”(Gyobutsu). So at Gyobutsuji we endeavor to honor our practice as Buddha, the reality of all things and beings. Life at the monastery is also an expression of our trust that genuine practice as an offering and support to all things. In Bendowa, Dogen Zenji writes, At this time [of zazen], earth, grasses and trees, fences and walls, tiles and pebbles, all things in the dharma realm in ten directions, carry out buddha work. Therefore, everyone receives the benefit of wind and water movement caused by this functioning, and all are imperceptibly helped by the wondrous and incomprehensible influence of Buddha to actualize the enlightenment at hand 2 To some the phrase “earth, grasses and trees, fences and walls, tiles and pebbles, all things in the dharma realm in ten directions, carry out buddha work” might appear to be a religious or even mystical abstraction, but since moving to Gyobutsuji I’ve become more aware of how trees, for example, really do support Buddha’s work, the process of awakening in practice. Trees are an essential element to sustaining life and practice at Gyobutsuji in a very concrete way. To prepare for winter at the monastery, for example, firewood must be cut and stacked since our primary source of heating is a wood burning stove. It’s a lot of work, but in that work it becomes easier to understand that the most important, essential things sustaining us in this life are gifts of the universe: I gather fallen limbs for kindling and cut and harvest the wood of dead trees; then on cold days I burn the wood to sustain my own life. Each tree that offers itself has its own history and function as a part of the forest. The tree I harvest to warm myself has grown over the course of many years, offering itself as a home to birds, squirrels, insects and other creatures. It has unwaveringly anchored the surrounding soil with its roots and rejuvenated it with its fallen leaves. It has helped to make the air suitable to breathe by cleansing it of carbon dioxide and other toxins. I pay nothing for the wood but a bit of sweat and effort; it is offered to me freely and abundantly. Observing these gifts has instilled in me a real sense of connection and gratitude for the beautiful trees on the monastery property. In my view it is not necessary to call ourselves “eco-Buddhists” or strive to create a sort of “Zenvironmentalism.” Practice is already about caring for our lives, and our lives include everything we encounter. So fundamentally, one does not necessarily need to become a disciple of “environmentalism”, “Buddhism”, or any “ism,” for that matter. We simply need to keep making an effort to wake up to the reality of life unfolding before us and to respond to it as fully as we can. Zazen is our guide, teacher and practice for this waking up to life, and I will write about that a bit more in the latter part of this essay. The Temple Property In Tenzokyokun3, Dogen wrote about the attitude one can adopt to express sincere practice when cooking for an assembly of practitioners. Consider this passage from the text: The Zen’en Shingi says, “Respected by society, though peacefully apart, the sangha is most pure and unfabricated.” Now I have the fortune to be born as a human being and prepare food for the three jewels (Buddha, dharma, and sangha). Is this not great karmic affinity? We must be very happy about this. 4 The sangha, or practice community, is of course a very important element in Buddhist teaching and practice. Along with the Buddha and the dharma, it is one of the beloved Three Treasures. Yet in his teachings Dogen Zenji refers to a sangha much larger than any particular group of practitioners. From an absolute perspective, in fact, our sangha is the community of all life, and our practice temple is the entire earth and sky. The “food” we offer is our practice of nurturing and supporting other things and beings, as they support and nurture us. Dogen also wrote in Tenzokyokun: Zen Master Baoming Renyong said, “Guard the temple properties as if they were your own eyes.” Respect [the temple food] as if it were for the Emperor. An ancient said, “When steaming rice, regard the pot as your own head; when washing rice, know that the water is your own life.” 5 Here Dogen Zenji is again speaking of practice beyond just cooking in the kitchen. Throughout Tenzokyokun he shows us metaphorically how best to meet our lives with our total being, presenting us with a sort of instruction manual for allowing zazen to guide our daily activities. The pot which cooks our food deserves careful handling and respect because it serves us in sustaining our life and practice. When we see clearly, we see the the tools that serve us are actually extensions of our own bodies, rather than disposable commodities we can throw into a landfill once their sheen has dulled a bit. When we care for the things that serve us, we care for ourselves. And by extending the life of our tools and appliances through such care, we in turn consume less, extending our care to our natural environment. The water which cooks our rice literally becomes part of our body when we eat the rice. We can live only a very short time without clean water; water really is inseparable from our life and the lives of all living beings. The water used for drinking, cooking and cleaning at Gyobutsuji is deposited into a cistern by our rain collection system, and simple gravity-fed plumbing brings the water to the building. The summer of 2012 was very dry at the monastery; I understand our local area experienced the worst drought in many years during those months. I had to conserve water as best I could during the drought, and as I watched the precious drops coming down when it did finally rain, it was very clear to me I was witnessing the gift of life falling from the sky. It’s so easy to take something so essential to our lives for granted, such as water, when it seems abundant. But these days it’s clear it’s vital that we care for our water sources on this planet, and in some parts of the world clean water is indeed seen as a rare and precious commodity. The temple properties mentioned in Tenzokyokun include the rivers, oceans, trees, earth and air we breathe. Truly these things are essential in sustaining our lives; we cannot survive without them. Again from an absolute perspective, they are indeed part of the very contents of our own bodies. In Tenzokyokun Dogen Zenji also describes how zazen manifests in our daily practice lives as the three minds (sanshin). Here he describes what he called roshin, or nurturing mind: As for what it called nurturing mind, it is the mind of mothers and fathers. For example, it is considering the three treasures as a mother and father thinks of their only child. Even impoverished, destitute people firmly love and raise an only child. What kind of determination is this? Other people cannot know it until they become mothers and fathers. Parents earnestly consider their child’s growth without concern for their own wealth or poverty. They do not care if they are hot or cold but give their child covering or shade. In parents’ thoughtfulness there is this intensity. People who have aroused this mind comprehend it well. Only people who are familiar with this mind are truly awake to it. Therefore, watching over water and over grain, shouldn’t everyone maintain the affection and kindness of nourishing children? 6 Today many of us may be turned off by the parental analogy when it comes to helping others. It may seem to smack of an “I know what’s best for you better that you do” attitude. But here Dogen is describing an approach rooted in the heart, detailing the attitude, perhaps, that Jesus proffered as “Love thy neighbor as thyself.” Seen once more from an absolute perspective, Dogen is recognizing that all animate and inanimate things are our neighbors, are indeed our family, our own body. Gathering Flowers Next I’d like to take a look from a passage from the chapter entitled “Flowers” of the Dhammapada, a very early record of some teachings of Shakyamuni Buddha: Knowing this body is like foam, fully awake to its mirage-like nature, cutting off Mara’s flowers, one goes unseen by the King of Death. Death sweeps away the person obsessed with gathering flowers, as a great flood sweeps away a sleeping village. The person obsessed with gathering flowers, insatiable for sense pleasures, is under the sway of Death. As a bee gathers nectar and moves on without harming the flower, its color, or its fragrance, Just so should a sage walk through a village. 7 This passage states that those who see their own impermanence, who directly face the inevitability of their own deaths, go “unseen by the King of Death.” In traditional Buddhist cosmology Yama is the king of death, ruling over those reborn into the lower realms of existence. So death here can be equated with suffering, or transmigration through the six realms of existence. The Buddha taught that from one rebirth to the next we move through these six realms (the heavenly realm, the realm of asuras or fighting beings, the human realm, the animal realm, the realm of hungry ghosts, and the hell realm) propelled by the results of our actions, or karma. We also move through these realms during our present life. They manifest moment by moment as cycles of ever-changing states of mind. Existence in these states of mental suffering during our current lives is rooted in a faulty approach to life in general. We may go through life desperately gathering the flowers we crave and avoiding the weeds we hate. This attitude is centered in a misguided sense of self, a sense that each thing the self encounters is simply an object to be considered only in relation to its own desires. It is very different from the nurturing mind described above. The flowers we gather may distract us and seemingly soothe our pain for some time, but sooner or later they wither, leaving us only the craving to gather more flowers. So the cycle of suffering is perpetuated in this way. For example, a person might buy a big, powerful new car and drive proudly into the euphoria of the heavenly realm. His friends compliment and even envy him, and he turns heads at traffic lights in his shiny new ride. It seems he has the world at his feet when he feels that surge of power as he zooms down the highway in style. But when it’s time to fill up the gas tank, make the first car payment, and pay the auto insurance bill, the petals of the “new car flower” begin to droop. Eventually the car’s paint fades, the body style becomes dated, and his carriage just doesn’t seem to have the get-up-and-go it used to. But he can remedy his woes by upgrading his stereo or buying a set of cool new rims. Eventually the solution for regaining that old excitement is to trade in his old ride for something newer and better, and of course the cycle continues…So does he own the car or does it own him? Does he drive it, or is he being driven blindly through the various realms of suffering? No matter how many flowers we gather in this way, whether it be cars, clothing, electronics, or whatever, sooner or later we end up with a handful of weeds, finding ourselves being blindly dragged around in a cycle of suffering. And of course this does not even begin to address the issue of the impact such flower gathering has on our environment and its inhabitants. Modern flower gathering has become increasingly powerful as consumer culture becomes more efficient in producing almost instantaneous gratification. We can quickly get almost anything imaginable by simply typing in some letters and numbers on our computer or phone. Our choices seem limitless, making it possible to find just the right item to “express our individuality” or temporarily placate our individual yearnings. We buy the latest smart phone, upgrade to a newer computer, and trade in our cars when the newest models arrive at the dealer. We follow fashion trends, updating our wardrobes and buying accessories we don’t really need. And so on. But today’s fastest, most powerful computer is obsolete tomorrow, and styles change far faster than our clothes wear out. Where do our faded flowers, our discarded toys and vanities, finally end up? What effect does this gathering and withering of our flowers have on the Earth upon which we live? Of course we can’t totally blame any one segment of society for the origin of consumer culture. Consumers, product designers, manufacturers, advertisers, retailers, etc.— all of us are responsible; this is a “spiritual” problem on a mass scale. It is rooted fundamentally in our perception of the relationship we have with our environment. From my perspective, an environmentally sound approach to living is an essential aspect of practice, an expression of zazen in daily living, if you will. At the bottom of the environmental crisis is the fundamental issue of how we face our relationship with ourselves, other beings, things and situations. We can see these as objects to pursue, manipulate, avoid, or ignore according to our preferences, or we can see them as the contents of our very own lives to be cared for as best we can. Dogen Zenji expressed it this way:

Therefore flowers fall even though we love them; weeds grow even though we dislike them. Conveying oneself toward all things to carry out practice-enlightenment is delusion. All things coming and carrying out practice-enlightenment through the self is enlightenment. 8 The things we love, the flowers we chase after, are impermanent and always changing, and we cannot hold on to them forever. The excitement of the purchase fades, and the products we buy decay or go out of style. The weeds of disappointment, sorrow, and conflict inevitably sprout in our lives, no matter how many flowers we gather. Yet we tend to forget the organic material provided both by life’s fallen flowers and its weeds are fertilizer for the soil of our living. They are instructors in the truths of dependent origination and our own suffering, if we can only be still enough to receive their teachings. But too often we simply go on searching for the next patch of flowers to pick, rather than facing the here and now and cultivating the wisdom and compassion that grow only by accepting both the negative and the positive as lessons life offers us moment by moment. “Conveying oneself toward all things” is attachment to flower gathering, the way human beings usually approach their lives. This is an outlook based upon the pursuit of what we want, the avoidance of what we don’t like, and the ignoring of what we find uninteresting. We deny or overlook the wisdom imparted by fallen flowers and sprouting weeds, and we protect, defend, and bolster our agendas at all costs, lest we end up “losers” or worse. It’s as if we are trying to stuff everything around us it into our bag of ego fulfillment. Social entities play out this scenario when they impose themselves on the natural environment, approaching it as a commodity to be utilized rather than caring for it as the delicate, sustaining source of of our shared life. This approach is based in delusion. It’s the root of irresponsibility, rigidity, passivity, aggression, and suffering. It’s our fundamental problem, and the way of zazen is the medicine for this illness. I couldn’t help but feel I was standing face-to-face with an emblem of this subject-object approach to nature and its role in consumer culture when here in Arkansas I saw something very surprising to me: two full-sized stuffed black bears mounted in the sporting goods section of a nation-wide chain department store. They reminded me of one way Uchiyama Roshi contrasted our thoughts and desires about reality and realityas it is. He said reality is like a live, swimming fish and clinging to our thoughts and emotions about reality is like a fish that has been killed, processed and cooked for our consumption. I think part of Uchiyama Roshi’s point was that although we of course must nourish ourselves by cooking some part of reality into our thoughts about it, we too often prefer the processed reality over the living and breathing reality, and we try to live at the dinner table of our own cooked-up perceptions and preferences. In my view the departments store bears seemed symbols of the type of processing we do when we attempt to make a trophy of the very life force that sustains us. Consumer culture is ironically cutting us off from our life-giving environment even as we attempt to process it into objects we can manipulate and possess. Paying Attention An old story relates how a monk asked Zen Master Ikkyu Sojun, “What is the essence of the Dharma?” In response the master simply writes the word attention with a brush. Expecting more, the monk asks, “Is that all?”, and Ikkyu this time writes attention,attention. In frustration the monk now exclaims, “What’s so deep about that?” The master calmly just brushes attention, attention, attention.9 The busyness of modern human life, embedded in and dependent upon a technology most of us have little functional understanding of, has in a sense made it more difficult to be intimate with our own lives, lives infinitely interconnected with other beings and things. It seems it’s becoming more and more difficult to observe cause and effect in our daily living— more difficult to pay attention to the effects of our behavior and act responsibly as we move through life. Of course we all now know, for example, when people drive cars powered with gasoline, environmentally harmful substances are released into the air as exhaust, and we know when we throw something into the garbage it likely will end up buried in the Earth, remaining there for thousands of years. It is of course possible to further educate ourselves concerning the environmental impact of these processes, but such knowledge can remain abstract and unlikely to affect us since we don’t directly see the consequences of our actions. This point was brought home to me some time ago when I was working for some friends. They asked me to wash the siding of their house with a cleaning solution I considered toxic. I hesitated telling them I didn’t like using the solution; after all, it was their house and they were employing me to do a job. And did using just a bit of the solution really have an ill effect on the environment? When I finished the job, I didn’t know what to do with the solution, so I poured a bit on a bare spot of ground, thinking the soil would likely filter or dilute the harmful elements before they could really do any damage. To my great dismay, earthworms immediately emerged from the surface of the ground where I poured the stuff, writhing and apparently trying to escape. It was difficult to see and take responsibility for that, but the directness of the experience had a lasting impact. Yet of course technology can actually help us observe cause and effect and live more responsively if we use it wisely. It, like all things, in one way or another is expounding the dharma. Technological development is not the problem; the problem is rooted in our relationship to that technology and the developmental direction we take it. Before living at this place powered by solar electrical energy, for example, I seldom took note of the fact that my life is directly sustained by the sun. Of course I knew intellectually that all life on Earth is dependent upon solar energy, but now when I’m working on my computer, for example, I’m amazed when I pause to think the electricity I’m using has been converted directly from sunlight by our solar energy system. This energy is an immeasurable gift, vital and abundant, as is the air we breathe and the water we drink. These are such essential, sustaining life elements, and they are offered to us freely. Yet how often do we recognize such limitless support? The electrical system is my teacher, in fact. On cloudy days I must pay extra attention to my electricity consumption. The solar harvesting system at Gyobutsuji is a bit underpowered, to tell you the truth, so on some less sunny days I turn up the temperature of our little refrigerator to conserve energy. It’s a balancing act between how long I can keep the food fresh and how well I can keep the system batteries charged up to a healthy level. If I turn up the refrigeration for too long, the food goes bad. If I tax the system batteries too much, their functional life is shortened, which is detrimental to the environment (through the production of new batteries and the disposal of the old ones), and the monastery budget is stressed. So it’s apparent that my management of electricity usage has an impact. Of course this is always the case, in any setting, and everyone’s energy consumption has an effect on our environment; yet it’s more difficult to see this when embedded in the busyness of modern life. Gyobutsuji, however, sometimes seems to me a giant mirror in which the effects of my actions are constantly reflected. For instance, one spring I noticed a skink (a lizard that looks like a snake with legs) was living in a space between some boards on our outside deck. It was a beautiful little creature, with florescent blue coloring on its back and tail, and a glowing orange-red patch under its neck. Over the weeks, it seemed to me he had become a member of the monastery sangha. I saw him often while I was outside working or having breakfast looking out into the valley. Sometimes he would be lying motionless on the deck, warming himself in a patch of sun; other times he would be skittering around, checking spaces between boards for one of the big black carpenter ants that are so common on the property. I realized his presence was likely somewhat responsible for the fact that relatively few insects seemed to be finding their way inside the building. One day I finally carved out some time to clean and organize the storage room that had for weeks been haphazardly accumulating heaps of recycling, tools, and supplies. In the course of setting out all of the contents of the room for organization, I placed the black pan I use for changing the oil in our car on the ground near the deck, away from everything else. I had emptied its contents into a recycling container, but some residual oil remained around the inner part of the pan, and I had not yet not gotten around to putting the whole pan into another larger container to prevent any chance of making a mess. When, after a few hours of work, I went to attend to the oil collecting pan, I found my friend the skink there, motionless as if he were sunning himself. I was heartbroken, however, because of course he had died there in the remnants of used motor oil. It must have seemed to him the perfect place for sunning, with all of the heat being absorbed by the dark oil. If I had paid better attention, I would have cared for my surroundings with more mindfulness and spared my little companion his untimely death. Of course it was a very hard lesson for me, but it was hardest of all on the unfortunate skink. Giver, Receiver and Gift Let’s now return to the verse from the Dhammapada: As a bee gathers nectar and moves on without harming the flower, its color, or its fragrance, Just so should a sage walk through a village. In the early days of Buddhism, when this verse originated, it must have been clear to the monks and nuns walking through the streets of their local villages that they were sustained by the generosity of those that offered them food. Perhaps a reason they were forbidden to work was to minimize the danger of developing a false sense of independence, an attitude of, “I work hard to sustain myself; I don’t owe anyone.” In reality, we can receive nothing that was not produced through the effort and sacrifice of countless beings, even if we “earn it” through our own labor. Where would any of us be without the farmers and other agricultural workers, for example, who produce our food? Few of us labor directly in the cultivation of the bulk of what we eat these days, but we can feel entitled to a relatively cheap, wholesome supply of food if we are not careful. And as I mentioned earlier, who of us could repay the sun, Earth, and sky for the life-sustaining gifts they continually bestow upon us? It’s clear the passage above from the Dhammapada was an exhortation to monks and nuns to do no harm as they relied on the community of villagers for their physical sustenance. They were expected to receive just enough to sustain their practice, being mindful not to overly tax their benefactors with requests for support. But monks were also expected to give something in return for what they received. In fact, simply providing the opportunity for people to practice giving was considered one of their primary responsibilities, as was their offering of Buddhist teachings to their supporters. Giving and receiving happened spontaneously; giver, receiver, and gift were one, supporting and giving life to each other in practice, just as a bee, a flower, and pollen simultaneously give and receive in the unfolding process of life. This reminds me of a poem my Zen teacher sometimes refers to in his teachings, It’s by the Japanese Zen monk/poet Ryokan. The poem is untitled, but it is probably abouttakuhatsu, traditional Buddhist alms gathering: With no-mind, the flower invites a butterfly With no-mind, the butterfly visits the flower When the flower opens, the butterfly comes When the butterfly comes, the flower opens I am the same I do not know the people And the people do not know me Without knowing We follow the heavenly emperor’s law. 10 But of course there is a lesson for all of us in the Dhammapada verses and Ryokan’s poem. It can seem almost impossible for any one of us to walk through our village, which actually includes the entire Earth, doing no harm, simply and sincerely giving and receiving. Things are just not so simple anymore. We now know that the lifestyle choices we make can have far reaching effects on other beings and things because of the karma (volitional action) created in our society’s processes of production and disposal of goods, for example. Modern life is so complex that we often have little idea how and from where our food and other products originate, and it can seem exhausting to attempt to analyze in detail the effects of our consumption. But we can make an effort to be responsible. Technology has also brought us the gift of access to almost unlimited sources of information that can help us find more clarity and behave more responsibly in our choices and activities. Still, even when we try our best to do what is wholesome, our options often don’t fall into clear black and white categories. I encountered such a situation at Gyobutsuji during a serious drought when the beautiful dogwood tree flanking our deck began to drop its leaves. To me the tree is a primary feature of the temple aesthetic. It is growing so close to the deck that its branches actually overhang and inhabit a corner of it, suggesting to me an offering of natural beauty and life energy that support Gyobutsuji’s practice. Observing the tree bloom and flourish with its big white flowers in the spring, produce seeds in late summer, turn a lovely, rich red before dropping its leaves in the fall, and quietly enduring in the cold of winter, is like watching an ongoing dharma talk: it is an inspiration and reminder of the teachings of Buddhism. So the tree has a special place in my heart; I feel it adds beauty and depth to Gyobutsuji. So I was distressed when, due to lack of water, the tree began losing its leaves during the summer’s drought of 2012. Because our cistern holds only so much water, I began hauling water from our pond in a wheelbarrow. I was happy to see that the shriveled leaves of the dogwood began to unfold after just a few hours of watering enabled by several trips to the pond, but I also noticed something disturbing at that point. The water I was taking from the pond contained countless living beings that were perishing in the process of watering the tree. It might seem obvious to some that the life of a beautiful dogwood tree is worth more that the lives of some water bugs, leeches, and skimmers, but was I really in a position to make such a judgement? A problem arises when we “know” we are right, when a conceptual position becomes an idol of sorts. It feels good to have some “ism” to rely on, something to placate our doubts and show us the way of action. But what happens when reality doesn’t seem to fit neatly into to any of the “isms” to which we our devoted? As a Buddhist, I have taken a vow to practice with a precept that proscribes killing. It seemed that watering the dogwood tree was a wholesome act, saving an element of the natural environment and nurturing an appreciated asset of the monastery grounds. But it turned out that I had to kill some beings in order to save another, and if I let the dogwood die, would that in a sense be an act of killing? To human beings, beautiful dogwood trees tend to be more valuable than leeches and water bugs, but that is only a human perspective. Buddhist teachings tell us any one view is inherently limited. In fact from another perspective, we know leeches and water bugs actually play an important role in sustaining aquatic ecosystems. They, as all beings, have value in the context of a larger whole. Still, difficult choices must sometimes be made in this life, and we can only do what we hope is best; life is just like that sometimes. But I do think it is important to observe and reflect and be open to the possibility there might have been a better way to proceed in such circumstances. That’s the way we cultivate awareness and become more skillful in acting responsibly. I did continue to water the dogwood until it revived, but I did so with a somewhat heavy heart and repentant attitude. I kept looking for some way to save the innocent creatures I scooped up from the pond. I did in fact find I could save some of them that had settled to the bottom of the wheelbarrow by not using the last bit of water of each load, pouring it back into the pond instead. Still, many beings were killed during that process, and I must take responsibility for that. If I’m honest with myself, I have to admit the dogwood tree is more valuable to me than the creatures I found swimming in the pond water, and that is why I continued to water the tree. But I also must keep in mind that is only my own limited view, not a correct or absolute view; in fact you could say it is indeed a deluded view. It is that recognition that motivates me to continue to try to find better ways to care for the monastery property that don’t involve the harming of life. I believe it’s only possible to progress in our understanding and practice when we take the time to reflect on our actions, perceptions, and views, recognizing ways in which we cause harm and acknowledging the limitations of our personal perspectives. Yes, I must make choices in order to take care of my life (which includes all I encounter), but I must be willing to see that these choices are always based on a limited point of view. Only then can I begin to make some sort of amends for the harm I may cause, expanding my limited views in order to make better choices in the future. In fact, a primary reason zazen practice is the foundation for practice at Gyobutsuji is that zazen allows us to release our clinging to preferences, views, biases, and sufferings, and it helps us open our hearts and minds. In zazen we let go of the boundaries between self and other, individual and universal. Zazen can do this because these boundaries actually exist only as concepts in our minds. To really understand this, we need to understand how to do zazen, and then actually do it. In zazen, one simply sits upright in the zazen posture, allowing the body, mind and breath to naturally harmonize. When thoughts, sensations, feelings, emotions, etc. enter the mind, the zazen practitioner neither entertains nor rejects them. In explaining this aspect of the practice, Zen Master Shunryu Suzuki Roshi said in zazen you should “leave your front door [of the mind] and back door open. Let thoughts come and go. Just don’t serve them tea.”11 Kosho Uchiyama Roshi called this “opening the hand of thought”. The original Japanese word he used, omoi, here translated as “thought”, actually includes all ideas, thoughts, emotions and feelings.12 Usually we grasp and cling to our sensations, emotions, thoughts and ideas as real and belonging to “me”. We invest ourselves in them completely. But Uchiyama Roshi said in zazen we loosen our “grip” on all of our experience and let thoughts, feelings, sensations, etc. simply arise, change, and fade away as they will. Then life is simply life; we neither cling to it nor reject it, and we manifest the “all things coming and carrying out practice-enlightenment through the self”mentioned above. When we allow zazen to be our guiding life endeavor, its effects begin to permeate our lives beyond the meditation cushion as well. Then we can loosen our grip on our certainties and allow other ways of seeing the world to help us grow in wisdom and insight. |

Where are we going?

Next consider this little anecdote Kosho Uchiyama Roshi included in his book Approach To Zen. I think it sums up modern culture’s predicament in relation to social values, technology, and the environmental crisis:

A comical fellow named Hachiko wanted to learn to ride a horse. The horse, however, was instinctively aware of the rider’s poor skill. When they passed by a grocery shop in a busy street the horse came to a halt and began helping himself to some vegetables, showing no sign of moving on. The angry shopkeeper goaded the animal on its rump with a stick. The horse reared and took off in a gallop down the street. The rider, Hachiko, stuck to the mane of the horse and tried not to be shaken. Hachiko’s friend happened to be walking down the street. At the sight of Hachiko’s frantic efforts he yelled, “Hey, Hachiko! Where are you going?”

“I dunno… ask the horse,” came the reply. 13

Our consumer society has become to a large degree, I think, a vacuum: a galloping black hole, plunging forward on to a “path to nowhere.” Where is it all headed? Where are we going?

The practice at Gyobutsuji is intended to help bring us back to the immediacy of life through intimacy with ourselves. It is intended to help bring us back to a wholesome direction, walking towards the awakening that is universal life.

Bees gather pollen, making their offering as they simply live out their lives.

Sitting zazen, gathering firewood, preparing meals, paying attention to our impact on the world and how we are impacted— these are ways we can make our lives offerings.

As an expression of my vow of practice in this life, I am trying to establish Gyobutsuji as a place where people, for a period of hours, days, weeks, or even years, can simplify their lives, focusing on zazen. I hope devoting some period of one’s life to concentrating on zazen will become a refuge and means for people to study their relationship with themselves and with the entirety of life. The better we come to understand this relationship, I believe, the better we can make an offering of peace and clarity to the society and world around us.

Such peace and clarity is rooted in the understanding that our practice is in itself an offering of the reality beyond the reach or our usual preferences, emotions, and thoughts. Dogen Zenji expressed this attitude in his writing Bendowa (Wholehearted Practice of the Way):

…There is a path through which the anuttara samyak sambodhi (complete perfect enlightenment) of all things returns [to the person in zazen], and whereby [that person and the enlightenment of all things] intimately and imperceptibly assist each other. Therefore this zazen person without fail drops off body and mind, cuts away previous tainted views and thoughts, awakens genuine buddha-dharma, universally helps the buddha work in each place, as numerous as atoms, where buddha-tathagatas teach and practice, and widely influences practitioners who are going beyond buddha, thereby vigorously exalting the dharma that goes beyond buddha. At this time, because earth, grasses and trees, fences and walls, tiles and pebbles, all things in the dharma realm in ten directions, carry out buddha work, therefore everyone receives the benefit of wind and water movement caused by this functioning, and all are imperceptibly helped by the wondrous and incomprehensible influence of buddha to actualize the enlightenment at hand. Since those who receive and use this water and fire extend the buddha influence of original enlightenment, all who live and talk with these people also share and universally unfold the boundless buddha virtue and they circulate the inexhaustible, ceaseless, incomprehensible, and immeasurable buddha-dharma within and without the whole dharma world. 13

Making Offerings of Our Flowers

The flower verses of the Dhammapada also remind me of a section of Dogen Zenji’sShobogenzo Shishobo (Four Embracing Actions of a Bodhisattva):

Even if we rule the four continents, in order to offer teachings of the true Way, we must simply and unfailingly not be greedy. It is like offering treasures we are about to discard to those we do not know. We give flowers blooming on the distant mountains to the Tathagata, and offer treasures accumulated in past lives to living beings.15

So the essential point of our practice is not necessarily to become the righteous sage or quintessential environmentalist. It is more that we offer our own flower gathering up to life itself. This is what we do in zazen. Likewise, in our daily lives, we allow our lives to blossom in harmony with everything we encounter, and we allow that blossoming to be an offering. Instead of gathering flowers to satisfy our desires, we come to see all life as a treasure we all share, so there is no need for greed. We cultivate and nurture the flower of life rather than trying to make it a possession, learning to care for our shared treasures as our offering. A life based upon the way of zazen, a life of practice, does not require that we sacrifice our joy to the larger community of human beings or to even the entire Earth and sky; true renunciation involves finding our joy in nurturing what is wholesome for our own lives, a life that is shared with all things and beings.

I feel compelled to say that I’m not presuming I’m removed from the environmental crisis because I live off-grid in a remote are. This is far from the truth, in fact I’m painfully aware of the many ways I still am contributing to the problem. In fact none of us can totally extricate themselves from the crisis, no matter how hard we try; we always share this life and its problems with all beings.

Yet this shared responsibility is our source of hope as well. We may not see solutions to all of our environmental issues in our lifetimes, but when we practice here and now with awareness and responsibility, letting zazen be our teacher and guide, enlightened activity is manifest in this world. And that has an effect, even in ways we cannot fully understand.

The melodious sound continues to resonate as it echoes, not only during sitting practice, but before and after striking sunyata [emptiness], which continues endlessly before and after a hammer hits it. Not only that, but all things are endowed with original practice within the original face, which is impossible to measure. 16

— Dogen Zenji in Bendowa

Notes

1 Translated by Shohaku Okumura

2 from The Wholehearted Way, a Translation of Eihei Dogen’s Bendowa, with Commentary by Kosho Uchiyama Roshi; Translated by Shohaku Okumura and Taigen Daniel Leighton

3 For an excellent commentary on Tenzokyokun, see Kosho Uchiyama Roshi’s How to Cook Your Life.

4 from Dogen’s Pure Standards for the Zen Community, translated by Taigen Daniel Leighton and Shohaku Okumura

5 from Dogen’s Pure Standards for the Zen Community, translated by Taigen Daniel Leighton and Shohaku Okumura

6 from Dogen’s Pure Standards for the Zen Community, translated by Taigen Daniel Leighton and Shohaku Okumura

7 from The Dhammapada: A New Translation of the Buddhist Classic with Annotations, translation and annotations by Gil Fronsdal

8 translation from the book Realizing Genjokoan: The Key to Dogen’s Shobogenzo by Shohaku Okumura

9 My thanks to the ToDo Institute of Vermont for reminding me of this story in as issue of its journal Thirty Thousand Days.

10 translated by Shohaku Okumura

11 See David Chadwick, Crooked Cucumber: The Life and Zen Teachings of Shunryu Suzuki, p.301.

12 See Opening the Hand of Thought by Kosho Uchiyama,,p.179, n. 22.

13 from Approach to Zen by Kosho Uchiyama Roshi, translated by Tom Wright, Stephen Yenik and Fred Stober

14 from The Wholehearted Way, a Translation of Eihei Dogen’s Bendowa, with Commentary by Kosho Uchiyama Roshi; Translated by Shohaku Okumura and Taigen Daniel Leighton

15 translated by Shohaku Okumura Roshi

16 from The Wholehearted Way, a Translation of Eihei Dogen’s Bendowa, with Commentary by Kosho Uchiyama Roshi; Translated by Shohaku Okumura and Taigen Daniel Leighton

Next consider this little anecdote Kosho Uchiyama Roshi included in his book Approach To Zen. I think it sums up modern culture’s predicament in relation to social values, technology, and the environmental crisis:

A comical fellow named Hachiko wanted to learn to ride a horse. The horse, however, was instinctively aware of the rider’s poor skill. When they passed by a grocery shop in a busy street the horse came to a halt and began helping himself to some vegetables, showing no sign of moving on. The angry shopkeeper goaded the animal on its rump with a stick. The horse reared and took off in a gallop down the street. The rider, Hachiko, stuck to the mane of the horse and tried not to be shaken. Hachiko’s friend happened to be walking down the street. At the sight of Hachiko’s frantic efforts he yelled, “Hey, Hachiko! Where are you going?”

“I dunno… ask the horse,” came the reply. 13

Our consumer society has become to a large degree, I think, a vacuum: a galloping black hole, plunging forward on to a “path to nowhere.” Where is it all headed? Where are we going?

The practice at Gyobutsuji is intended to help bring us back to the immediacy of life through intimacy with ourselves. It is intended to help bring us back to a wholesome direction, walking towards the awakening that is universal life.

Bees gather pollen, making their offering as they simply live out their lives.

Sitting zazen, gathering firewood, preparing meals, paying attention to our impact on the world and how we are impacted— these are ways we can make our lives offerings.

As an expression of my vow of practice in this life, I am trying to establish Gyobutsuji as a place where people, for a period of hours, days, weeks, or even years, can simplify their lives, focusing on zazen. I hope devoting some period of one’s life to concentrating on zazen will become a refuge and means for people to study their relationship with themselves and with the entirety of life. The better we come to understand this relationship, I believe, the better we can make an offering of peace and clarity to the society and world around us.

Such peace and clarity is rooted in the understanding that our practice is in itself an offering of the reality beyond the reach or our usual preferences, emotions, and thoughts. Dogen Zenji expressed this attitude in his writing Bendowa (Wholehearted Practice of the Way):

…There is a path through which the anuttara samyak sambodhi (complete perfect enlightenment) of all things returns [to the person in zazen], and whereby [that person and the enlightenment of all things] intimately and imperceptibly assist each other. Therefore this zazen person without fail drops off body and mind, cuts away previous tainted views and thoughts, awakens genuine buddha-dharma, universally helps the buddha work in each place, as numerous as atoms, where buddha-tathagatas teach and practice, and widely influences practitioners who are going beyond buddha, thereby vigorously exalting the dharma that goes beyond buddha. At this time, because earth, grasses and trees, fences and walls, tiles and pebbles, all things in the dharma realm in ten directions, carry out buddha work, therefore everyone receives the benefit of wind and water movement caused by this functioning, and all are imperceptibly helped by the wondrous and incomprehensible influence of buddha to actualize the enlightenment at hand. Since those who receive and use this water and fire extend the buddha influence of original enlightenment, all who live and talk with these people also share and universally unfold the boundless buddha virtue and they circulate the inexhaustible, ceaseless, incomprehensible, and immeasurable buddha-dharma within and without the whole dharma world. 13

Making Offerings of Our Flowers

The flower verses of the Dhammapada also remind me of a section of Dogen Zenji’sShobogenzo Shishobo (Four Embracing Actions of a Bodhisattva):

Even if we rule the four continents, in order to offer teachings of the true Way, we must simply and unfailingly not be greedy. It is like offering treasures we are about to discard to those we do not know. We give flowers blooming on the distant mountains to the Tathagata, and offer treasures accumulated in past lives to living beings.15

So the essential point of our practice is not necessarily to become the righteous sage or quintessential environmentalist. It is more that we offer our own flower gathering up to life itself. This is what we do in zazen. Likewise, in our daily lives, we allow our lives to blossom in harmony with everything we encounter, and we allow that blossoming to be an offering. Instead of gathering flowers to satisfy our desires, we come to see all life as a treasure we all share, so there is no need for greed. We cultivate and nurture the flower of life rather than trying to make it a possession, learning to care for our shared treasures as our offering. A life based upon the way of zazen, a life of practice, does not require that we sacrifice our joy to the larger community of human beings or to even the entire Earth and sky; true renunciation involves finding our joy in nurturing what is wholesome for our own lives, a life that is shared with all things and beings.

I feel compelled to say that I’m not presuming I’m removed from the environmental crisis because I live off-grid in a remote are. This is far from the truth, in fact I’m painfully aware of the many ways I still am contributing to the problem. In fact none of us can totally extricate themselves from the crisis, no matter how hard we try; we always share this life and its problems with all beings.

Yet this shared responsibility is our source of hope as well. We may not see solutions to all of our environmental issues in our lifetimes, but when we practice here and now with awareness and responsibility, letting zazen be our teacher and guide, enlightened activity is manifest in this world. And that has an effect, even in ways we cannot fully understand.

The melodious sound continues to resonate as it echoes, not only during sitting practice, but before and after striking sunyata [emptiness], which continues endlessly before and after a hammer hits it. Not only that, but all things are endowed with original practice within the original face, which is impossible to measure. 16

— Dogen Zenji in Bendowa

Notes

1 Translated by Shohaku Okumura

2 from The Wholehearted Way, a Translation of Eihei Dogen’s Bendowa, with Commentary by Kosho Uchiyama Roshi; Translated by Shohaku Okumura and Taigen Daniel Leighton

3 For an excellent commentary on Tenzokyokun, see Kosho Uchiyama Roshi’s How to Cook Your Life.

4 from Dogen’s Pure Standards for the Zen Community, translated by Taigen Daniel Leighton and Shohaku Okumura

5 from Dogen’s Pure Standards for the Zen Community, translated by Taigen Daniel Leighton and Shohaku Okumura

6 from Dogen’s Pure Standards for the Zen Community, translated by Taigen Daniel Leighton and Shohaku Okumura

7 from The Dhammapada: A New Translation of the Buddhist Classic with Annotations, translation and annotations by Gil Fronsdal

8 translation from the book Realizing Genjokoan: The Key to Dogen’s Shobogenzo by Shohaku Okumura

9 My thanks to the ToDo Institute of Vermont for reminding me of this story in as issue of its journal Thirty Thousand Days.

10 translated by Shohaku Okumura

11 See David Chadwick, Crooked Cucumber: The Life and Zen Teachings of Shunryu Suzuki, p.301.

12 See Opening the Hand of Thought by Kosho Uchiyama,,p.179, n. 22.

13 from Approach to Zen by Kosho Uchiyama Roshi, translated by Tom Wright, Stephen Yenik and Fred Stober

14 from The Wholehearted Way, a Translation of Eihei Dogen’s Bendowa, with Commentary by Kosho Uchiyama Roshi; Translated by Shohaku Okumura and Taigen Daniel Leighton

15 translated by Shohaku Okumura Roshi

16 from The Wholehearted Way, a Translation of Eihei Dogen’s Bendowa, with Commentary by Kosho Uchiyama Roshi; Translated by Shohaku Okumura and Taigen Daniel Leighton

|

Shoryu Bradley is the guiding monk of Gyobutsuji, a small monastic practice place in the Ozark Mountains of Northwest Arkansas, and a Dharma heir of Shohaku Okumura Roshi. Gyobutsuji holds ten monthly “zazen only” sesshins per year in the style of Kosho Uchiyama Roshi, and it follows an intensive daily monastic schedule consisting of zazen, study, and work. Shoryu began residing at Gyobutsuji in 2012. Today the monastery hosts a few long-term residents as well as shorter-term visitors.

|