- Home

- Process Worldview

- Community

- Art and Music

- Whitehead and Process Thinking

- Podcasts

- Spirituality

- Ecological Civilization

- Education

- Contact

- Social Justice

- Science

- Animals

- Sacred Poems

- Whitehead Videos

- Index of All Titles

- Practicing Process Thought

- Process Spirituality: A Spiritual Alphabet

- Recent Posts

The Historical and Metaphysical Problems

with the Traditionalist Critique of Modernity

Jared Morningstar

reposted from Medium, 4/12/21

Lately, I’ve become more and more skeptical regarding Traditionalist narratives (and polemics) of Modernity. Here’s a two insights on this topic which percolated as I chatted with a friend yesterday.

The first point is of a more historical/empirical nature. Basically, I am simply not convinced that Modernity is as dissimilar to or as discontinuous with previous historical epochs as the Traditionalists make it out to be. Yes, there are significant shifts which have happened, but likewise there were significant shifts which happened following the Bronze Age collapse, and it seems that the Traditionalist perspective tends to see the before and after here as both legitimately traditional (and thus good), though obviously the more sophisticated expositors of this perspective do draw important distinctions here. But regardless, the point stands that you see a significant effort to subsume perspectives as disparate as a kind of ancient animism with the highly sophisticated Neoplatonic metaphysics of much later Abrahamic monotheism.

I actually find this project very compelling — bridging these kinds of deep gaps — but it’s tiring to see such sophistication in this area, and then when it comes to analyzing Modernity, you find very essentializing methods which paper over complex and disparate histories — certainly Modernity is not a single movement (especially when you look at it globally) and to act as though all which has come about in this era is by definition anti-Tradition simply seems antithetical to critical (and historical) thought.

Islamic Calligraphy reading “Allah Hu”My second point is perhaps more creative. I don’t think the metaphysics of reifying Modernity to the extent many Traditionalists do is justifiable in light of the basic commitments of this perspective. The non-duality of Ultimate Reality (God, Brahman, Emptiness) reigns supreme in the Neoplatonic and Vedantist sources of Traditionalism and there is a deep continuity between this non-dual Ultimate and the contingent created cosmos — the things of the human world such as matter and historical events are not wholly separate from God, but rather a limited and partial expression of some particularized aspect of the Divine. Of course, in order for the Many to exist in relation to the One or the Particular in relation to the Absolute, there needs to be some account for absence of God which acts as a metaphysical polarity without any reality of its own. The most convincing accounts of this kind of metaphysics in my eyes includes both absolute being and absolute nothingness within the essence of Ultimate Reality.

Having covered the basic metaphysics of Traditionalism, I posit that the reification of Modernity and taking up an entirely reactionary stance against it is untenable. History and its developments express something of Ultimate Reality from this perspective — taking Modernity as so fundamental a rupture and as absolute privation of the True, the Good, and the Beautiful is to set up an autonomous being alongside God. Either Modernity is in some sense an expression of the Divine Will, and thus something from which we can learn and respond to constructively, or it is something so antithetical to the Divine that the metaphysical commitments to God’s omnipotence held is fundamentally threatened.

Of course, there are genuinely anti-Traditional aspects to Modernity, and certainly one of the moral demands of this age is to sort the wheat from the chaff and use discernment to the best of one’s ability. But so much of the Traditionalist critique of Modernity — at least in the articulations I see parroted online — is NOT discerning. It is not sorting the wheat from the chaff, but throwing the baby out with the bathwater.

Not everything good in this age is of an overtly religious character, and not everything bad in this age is novel and creative. Yes, modernity has destroyed religion in some devastating ways and there’s tragedy in that, but attempting to naively return to some imagined pre-modern religiosity, while living within Modernity is also going to be a locus of tragedy. Just as, for Christians, it was the Divine Will of God which demanded that Jesus Christ be crucified and enter Hell so that sin and death could be conquered, I believe there’s a certain Divine Wisdom in the death Modernity has brought to organized religion and even God himself.

When Jesus subsequently rose from the dead following his crucifixion, he was unrecognizable to his followers. So too will the resurrection of the existing religions following Modernity involve fundamental shifts, but these shifts will not be breaks from the Divine Will, but rather its fulfillment.

The first point is of a more historical/empirical nature. Basically, I am simply not convinced that Modernity is as dissimilar to or as discontinuous with previous historical epochs as the Traditionalists make it out to be. Yes, there are significant shifts which have happened, but likewise there were significant shifts which happened following the Bronze Age collapse, and it seems that the Traditionalist perspective tends to see the before and after here as both legitimately traditional (and thus good), though obviously the more sophisticated expositors of this perspective do draw important distinctions here. But regardless, the point stands that you see a significant effort to subsume perspectives as disparate as a kind of ancient animism with the highly sophisticated Neoplatonic metaphysics of much later Abrahamic monotheism.

I actually find this project very compelling — bridging these kinds of deep gaps — but it’s tiring to see such sophistication in this area, and then when it comes to analyzing Modernity, you find very essentializing methods which paper over complex and disparate histories — certainly Modernity is not a single movement (especially when you look at it globally) and to act as though all which has come about in this era is by definition anti-Tradition simply seems antithetical to critical (and historical) thought.

Islamic Calligraphy reading “Allah Hu”My second point is perhaps more creative. I don’t think the metaphysics of reifying Modernity to the extent many Traditionalists do is justifiable in light of the basic commitments of this perspective. The non-duality of Ultimate Reality (God, Brahman, Emptiness) reigns supreme in the Neoplatonic and Vedantist sources of Traditionalism and there is a deep continuity between this non-dual Ultimate and the contingent created cosmos — the things of the human world such as matter and historical events are not wholly separate from God, but rather a limited and partial expression of some particularized aspect of the Divine. Of course, in order for the Many to exist in relation to the One or the Particular in relation to the Absolute, there needs to be some account for absence of God which acts as a metaphysical polarity without any reality of its own. The most convincing accounts of this kind of metaphysics in my eyes includes both absolute being and absolute nothingness within the essence of Ultimate Reality.

Having covered the basic metaphysics of Traditionalism, I posit that the reification of Modernity and taking up an entirely reactionary stance against it is untenable. History and its developments express something of Ultimate Reality from this perspective — taking Modernity as so fundamental a rupture and as absolute privation of the True, the Good, and the Beautiful is to set up an autonomous being alongside God. Either Modernity is in some sense an expression of the Divine Will, and thus something from which we can learn and respond to constructively, or it is something so antithetical to the Divine that the metaphysical commitments to God’s omnipotence held is fundamentally threatened.

Of course, there are genuinely anti-Traditional aspects to Modernity, and certainly one of the moral demands of this age is to sort the wheat from the chaff and use discernment to the best of one’s ability. But so much of the Traditionalist critique of Modernity — at least in the articulations I see parroted online — is NOT discerning. It is not sorting the wheat from the chaff, but throwing the baby out with the bathwater.

Not everything good in this age is of an overtly religious character, and not everything bad in this age is novel and creative. Yes, modernity has destroyed religion in some devastating ways and there’s tragedy in that, but attempting to naively return to some imagined pre-modern religiosity, while living within Modernity is also going to be a locus of tragedy. Just as, for Christians, it was the Divine Will of God which demanded that Jesus Christ be crucified and enter Hell so that sin and death could be conquered, I believe there’s a certain Divine Wisdom in the death Modernity has brought to organized religion and even God himself.

When Jesus subsequently rose from the dead following his crucifixion, he was unrecognizable to his followers. So too will the resurrection of the existing religions following Modernity involve fundamental shifts, but these shifts will not be breaks from the Divine Will, but rather its fulfillment.

A Role for Tradition and Modernity

in the future of Religion

a process response to Jared Morningstar

Let's say that the values of Tradition include a sense of the sacred, a recognition that human life can be guided by God, an appreciation of community, and a respect for tradition itself. And let's say that the value of Modernity includes an appreciation of the value of the individual, a respect for science, a recognition of the possibility of progress, and a love of novelty. Can the two be combined? Let's hope so.

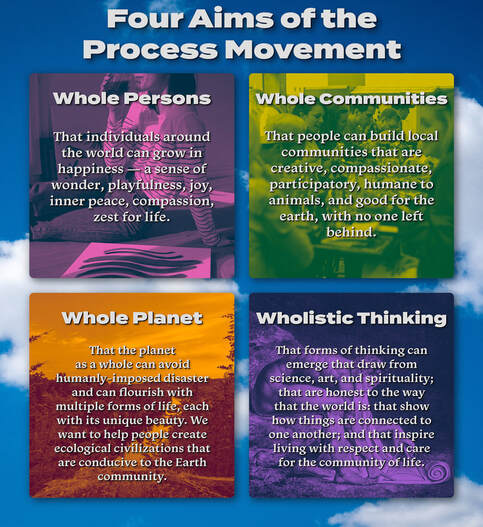

After reading the essay by Jared Morningstar, I began to hope so even more. I began to wonder if one of the positive values of Modernity might be that it contributes to a creative transformation of religion in two ways: by freeing those of us who are religious from the assumption that a love of God is antithetical to a love of life and by inspiring us to find God in, not apart from, four earthly hopes: whole persons, whole communities, a whole planet, and wholistic thinking.

From a process perspective, the embrace of these hopes is one way that we walk with God in this very life. Walking with God and walking in hope are two sides of a single coin: two sides of faith.

Make no mistake, for process thinkers God is within the walking but also more than this walking. God is a compassionate Life in whose heart we and all things live and move and have our being. There is a non-temporal side of God (the primordial nature) and a temporal side (the consequent nature). Together they form a dynamic whole that embraces the universe. This Life is more than us and transcends the universe in many ways. God is transcendent. Immanent, yes; but transcendent, too. However, we find this Life, not simply by focusing on divine transcendence and the journey of a soul to God, but also by a sense of the horizontal sacred: that is, a sense that the sacred is found as we develop "sacred" relations with the world.

To my mind, Morningstar's essay reminds us that have something to learn from Tradition and Modernity, neither to the exclusion of the other. With this in mind I offer an appreciatuve ?process" response to Morningstar's two critiques: one historical and one metaphysical.

History

The historical critique is that Traditionalists wrongly tend to see Modernity in monolithic, essentialist, and negative terms, neglecting its internal diversity, its global dimensions, and its contributions to the world. Traditionalists advocate a recovery of what they call Traditionalist sensibilities, as if the emergence of Modernity was a fall from a previous paradise, pure and simple, but in no way a fall upward. There is, for them a gulf between the Modernity and Traditionalism, with the former "bad" and the 'latter "good."

I agree with Morningstar, and lament the fact that, in the world of process philosophy and theology, perhaps especially as it has unfolded in China under the rubric of Constructive Postmodernism, Modernity has likewise been presented in monolithic, essentialist, and negative terms. To be sure, the Constructive Postmodernism of the kind advocated by the process-influenced Institute for Postmodern Development of China, with which I myself work, is different from the Traditionalism of, say, Seyyed Nasr with its neo-Platonic leanings. But Constructive Postmodernists and Traditionalists alike can make a bogeyman of what they call Modernity.

The problem is made ever more apparent when we consider, along with John Cobb, the many different meanings of Modernity, to which he alludes in his short note: "Is Process Theology Postmodern?" Noting that the very word has different meanings in the contexts of art, architecture, literature, philosophy, and theology, he turns to Whitehead's distinctive critique of one kind of Modernity.

Whitehead wrote a book entitled “Science and the Modern World,” in which the modern world is presented as ending. Although he does not use the term “postmodern,” he is clearly thinking of the “modern” as a mode of thought whose limitations have become apparent and that is being superseded. It is this depiction that suggested the term “postmodern” to me and others long before we knew of any use of the term by French philosophers. Whitehead shows that although the social, political, economic, and military characteristics of the modern world may continue to develop, modern science and modern philosophy are ending, and he is calling for a new beginning. Whitehead intends to be contributing to this new beginning.

In most areas, the beginning of the modern is hard to identify with any precision. The transition from the Medieval to the modern is gradual. This is true even with science. But in the case of philosophy the transition is quite abrupt. Whereas it is hard to say who is the first modern scientist, there is widespread agreement that “modern” philosophy began with Descartes in the middle of the seventeenth century. His philosophy was influenced by new scientific sensibilities and also contributed to giving definite form to the assumptions with which modern science became identified. The enormous success of the resulting science gave it among modern thinkers the highest prestige. Although philosophy went through drastic permutations, the understanding of nature associated with the natural sciences became a central part of the worldview of the modern world. (John Cobb, Ask Dr. Cobb, 2010, Process and Faith)

In his note Cobb then turns to the topic of God and notes that Whitehead's postmodern approach opens up possibilities for affirming traditional faith, albeit in a postmodern way. He writes:

These differences show up, among other places, in theology. Although Whitehead is very clear about the provisional and hypothetical character of all his cosmology and especially when he speaks of God, he has opened the door to quite direct statements about God and how God works in the world. Charles Hartshorne gave even fuller description of these matters with less qualification as to the status of what he said.

On the other hand, modernity in its later phases drastically questioned the capacity of human thought to understand reality in general and anything that transcended nature in particular. God was often flatly denied, and those who were not ready to give up the idea of God altogether typically emphasized the limitations and indirectness of all speech about God. These features of late modernity have been continued in deconstructive postmodernism. The deconstruction has been of the certainties and literal claims of early modernism rather than of the emphasis in late modernity on the constructive and often distorting work of the human mind in producing such ideas. Even if the value of some of Whitehead’s reconstructive proposals are accepted, this is in the context of emphasis on their hypothetical and perspectival character.

In short, for Cobb, Whitehead's philosophy provides a postmodern way of affirming and appreciating the role of God in human life and in the natural world. In this, Cobb's aims are not dissimilar from those of many Traditionalists. He wants to make space for the sacred. Morningstar's note takes us to an intriguing possibility in which Cobb is also interested: Can the sacred appear as the secular?

Metaphysics

Morningstar's metaphysical critique is that Modernity may well not be as bad as Traditionalists aver and that, if they are consistent with their own metaphysics, Traditionalists will rightly conceive modernity as an expression of divine will,

The Traditionalist metaphysic, explains Morningstar, is Neoplatonic and Vedantist in tone: The non-duality of Ultimate Reality (God, Brahman, Emptiness) reigns supreme in the Neoplatonic and Vedantist sources of Traditionalism. Given this way of thinking about Ultimate Reality, Morningstar points out that history and its developments express something of the Ultimate Reality, and that positing a radical rupture from Ultimate Reality unwittingly presents Modernity as autonomous in its own right. In his words:

History and its developments express something of Ultimate Reality from this perspective — taking Modernity as so fundamental a rupture and as absolute privation of the True, the Good, and the Beautiful is to set up an autonomous being alongside God. Either Modernity is in some sense an expression of the Divine Will, and thus something from which we can learn and respond to constructively, or it is something so antithetical to the Divine that the metaphysical commitments to God’s omnipotence held is fundamentally threatened

Process philosophers and theologians will agree with Morningstar on this inconsistency in Traditionalism, and disagree with the idea that the needed alternative need presume that, in thinking of the Divine, we must bring along "metaphysical commitments to God's omnipotence." A key feature of process philosophy and theology is that God truly exists as a compassionate and luring presence within the universe and within each human heart, that this luring presence transcends the universe as a cosmic Self with feelings and aims of its own, and that this Self is all-loving but not all-powerful. See, for example, Rabbi Bradley Artson's God Almighty? No Way!

Perhaps it goes without saying that this process way of thinking is itself antithetical to many and perhaps all Traditionalist sensibilities. A denial of omnipotence, traditionally understood, seems like a denial of God. But for process thinkers the denial is religiously meaningful, because it makes space for believing in a truly compassionate God who does not will violence, murder, rape, cruelty, and our current wholesale assault on a small but beautiful planet. Process thinkers believe that God's luring presence is powerful, but in a way that requires creaturely cooperation for its fulfillment. In the tradition of Modernity, they want to affirm a certain kind of creativity that is as real in its way, as is God's in God's way. Hence their affirmation of co-creativity. This best makes sense if we distinguish between Ultimate Reality and Ultimate Actuality, not unlike the way that Whitehead distinguishes between Creativity and the Primordial Nature of God.

Morningstar writes:

Just as, for Christians, it was the Divine Will of God which demanded that Jesus Christ be crucified and enter Hell so that sin and death could be conquered, I believe there’s a certain Divine Wisdom in the death Modernity has brought to organized religion and even God himself...When Jesus subsequently rose from the dead following his crucifixion, he was unrecognizable to his followers. So too will the resurrection of the existing religions following Modernity involve fundamental shifts, but these shifts will not be breaks from the Divine Will, but rather its fulfillment.

To my mind, these sentences give rise to the idea of a non-dual Ultimate Reality (with capital letters) that is manifest, expressed or revealed in all that happens in the world, including (1) the rise of modernity and its dethroning of religion and (2) tragic events such as the crucifixion of Jesus. It is as if Ultimate Reality has agency of its own and that all things are expressions of its will.

Whitehead wrestled with this question and arrived at two provocative ideas. The first is that, all things considered, it is best to deny Ultimate Reality this kind of agency and better to think that it (Ultimate Reality) is actual in virtue of its instances. The second is that there is a cosmic soul of the universe, God, who is continuously at work in the universe and who is the primordial but not exclusive expression of ultimate reality. Here is how he puts it in Process and Reality:

In all philosophic theory there is an ultimate which is actual in virtue of its accidents. It is only then capable of characterization through its accidental embodiments, and apart from these accidents is devoid of [11] actuality. In the philosophy of organism this ultimate is termed ‘creativity’; and God is its primordial, non-temporal accident.* In monistic philosophies, Spinoza's or absolute idealism, this ultimate is God, who is also equivalently termed ‘The Absolute.’ In such monistic schemes, the ultimate is illegitimately allowed a final, ‘eminent’ reality, beyond that ascribed to any of its accidents. In this general position the philosophy of organism seems to approximate more to some strains of Indian, or Chinese,thought, than to western Asiatic, or European, thought. One side makes process ultimate; the other side makes fact ultimate.

The upshot of this way of thinking is to say that ultimate reality is not an agent with a will of its own, but rather an unnamable depth which is manifest, expressed, and revealed in all things that have agency: God on the one hand, and finite creatures (quantum events, living cells, plants, and animals) on the other. God is that particular instance of creativity which beckons creatures toward creative expressions of their own creativity and absorbs their influence with tender care. God is powerful, but not all powerful. Things happen in the world which even God cannot prevent.

On this view, neither the rise of Modernity nor the crucifixion of Jesus can be conceived as a pure expression of God's will. Both are an outcome, at least in part, of the self-creativity of ultimate reality. They happen on their own. And yet both can also be conceived, at least in part, as responses to the will of God. After all, at a certain point in his life, God called Jesus to die on the cross, despite Jesus' own leanings to the contrary: "not my will but thy will, O Lord." Jesus aligned his own agency with God's will. And so, at this stage in history, might we humans do the same, whether we are Traditionalists or Constructive Postmodernists, or some blend. Our task at this time may well be to help usher into the world something new, with traces of tradition, traces of modernity, and traces of a future not contained by Tradition or Modernity (however conceived and related). This may be the great work: not to make gods of the past, traditional or modern, but to listen and respond to a call from Beyond, a Beyond that comes to us, not as a spatial hierarchy resting in the sky, but as a dream to be realized, belonging both to God and to us, in partnership.

- Jay McDaniel, 12/7/2021

After reading the essay by Jared Morningstar, I began to hope so even more. I began to wonder if one of the positive values of Modernity might be that it contributes to a creative transformation of religion in two ways: by freeing those of us who are religious from the assumption that a love of God is antithetical to a love of life and by inspiring us to find God in, not apart from, four earthly hopes: whole persons, whole communities, a whole planet, and wholistic thinking.

From a process perspective, the embrace of these hopes is one way that we walk with God in this very life. Walking with God and walking in hope are two sides of a single coin: two sides of faith.

Make no mistake, for process thinkers God is within the walking but also more than this walking. God is a compassionate Life in whose heart we and all things live and move and have our being. There is a non-temporal side of God (the primordial nature) and a temporal side (the consequent nature). Together they form a dynamic whole that embraces the universe. This Life is more than us and transcends the universe in many ways. God is transcendent. Immanent, yes; but transcendent, too. However, we find this Life, not simply by focusing on divine transcendence and the journey of a soul to God, but also by a sense of the horizontal sacred: that is, a sense that the sacred is found as we develop "sacred" relations with the world.

To my mind, Morningstar's essay reminds us that have something to learn from Tradition and Modernity, neither to the exclusion of the other. With this in mind I offer an appreciatuve ?process" response to Morningstar's two critiques: one historical and one metaphysical.

History

The historical critique is that Traditionalists wrongly tend to see Modernity in monolithic, essentialist, and negative terms, neglecting its internal diversity, its global dimensions, and its contributions to the world. Traditionalists advocate a recovery of what they call Traditionalist sensibilities, as if the emergence of Modernity was a fall from a previous paradise, pure and simple, but in no way a fall upward. There is, for them a gulf between the Modernity and Traditionalism, with the former "bad" and the 'latter "good."

I agree with Morningstar, and lament the fact that, in the world of process philosophy and theology, perhaps especially as it has unfolded in China under the rubric of Constructive Postmodernism, Modernity has likewise been presented in monolithic, essentialist, and negative terms. To be sure, the Constructive Postmodernism of the kind advocated by the process-influenced Institute for Postmodern Development of China, with which I myself work, is different from the Traditionalism of, say, Seyyed Nasr with its neo-Platonic leanings. But Constructive Postmodernists and Traditionalists alike can make a bogeyman of what they call Modernity.

The problem is made ever more apparent when we consider, along with John Cobb, the many different meanings of Modernity, to which he alludes in his short note: "Is Process Theology Postmodern?" Noting that the very word has different meanings in the contexts of art, architecture, literature, philosophy, and theology, he turns to Whitehead's distinctive critique of one kind of Modernity.

Whitehead wrote a book entitled “Science and the Modern World,” in which the modern world is presented as ending. Although he does not use the term “postmodern,” he is clearly thinking of the “modern” as a mode of thought whose limitations have become apparent and that is being superseded. It is this depiction that suggested the term “postmodern” to me and others long before we knew of any use of the term by French philosophers. Whitehead shows that although the social, political, economic, and military characteristics of the modern world may continue to develop, modern science and modern philosophy are ending, and he is calling for a new beginning. Whitehead intends to be contributing to this new beginning.

In most areas, the beginning of the modern is hard to identify with any precision. The transition from the Medieval to the modern is gradual. This is true even with science. But in the case of philosophy the transition is quite abrupt. Whereas it is hard to say who is the first modern scientist, there is widespread agreement that “modern” philosophy began with Descartes in the middle of the seventeenth century. His philosophy was influenced by new scientific sensibilities and also contributed to giving definite form to the assumptions with which modern science became identified. The enormous success of the resulting science gave it among modern thinkers the highest prestige. Although philosophy went through drastic permutations, the understanding of nature associated with the natural sciences became a central part of the worldview of the modern world. (John Cobb, Ask Dr. Cobb, 2010, Process and Faith)

In his note Cobb then turns to the topic of God and notes that Whitehead's postmodern approach opens up possibilities for affirming traditional faith, albeit in a postmodern way. He writes:

These differences show up, among other places, in theology. Although Whitehead is very clear about the provisional and hypothetical character of all his cosmology and especially when he speaks of God, he has opened the door to quite direct statements about God and how God works in the world. Charles Hartshorne gave even fuller description of these matters with less qualification as to the status of what he said.

On the other hand, modernity in its later phases drastically questioned the capacity of human thought to understand reality in general and anything that transcended nature in particular. God was often flatly denied, and those who were not ready to give up the idea of God altogether typically emphasized the limitations and indirectness of all speech about God. These features of late modernity have been continued in deconstructive postmodernism. The deconstruction has been of the certainties and literal claims of early modernism rather than of the emphasis in late modernity on the constructive and often distorting work of the human mind in producing such ideas. Even if the value of some of Whitehead’s reconstructive proposals are accepted, this is in the context of emphasis on their hypothetical and perspectival character.

In short, for Cobb, Whitehead's philosophy provides a postmodern way of affirming and appreciating the role of God in human life and in the natural world. In this, Cobb's aims are not dissimilar from those of many Traditionalists. He wants to make space for the sacred. Morningstar's note takes us to an intriguing possibility in which Cobb is also interested: Can the sacred appear as the secular?

Metaphysics

Morningstar's metaphysical critique is that Modernity may well not be as bad as Traditionalists aver and that, if they are consistent with their own metaphysics, Traditionalists will rightly conceive modernity as an expression of divine will,

The Traditionalist metaphysic, explains Morningstar, is Neoplatonic and Vedantist in tone: The non-duality of Ultimate Reality (God, Brahman, Emptiness) reigns supreme in the Neoplatonic and Vedantist sources of Traditionalism. Given this way of thinking about Ultimate Reality, Morningstar points out that history and its developments express something of the Ultimate Reality, and that positing a radical rupture from Ultimate Reality unwittingly presents Modernity as autonomous in its own right. In his words:

History and its developments express something of Ultimate Reality from this perspective — taking Modernity as so fundamental a rupture and as absolute privation of the True, the Good, and the Beautiful is to set up an autonomous being alongside God. Either Modernity is in some sense an expression of the Divine Will, and thus something from which we can learn and respond to constructively, or it is something so antithetical to the Divine that the metaphysical commitments to God’s omnipotence held is fundamentally threatened

Process philosophers and theologians will agree with Morningstar on this inconsistency in Traditionalism, and disagree with the idea that the needed alternative need presume that, in thinking of the Divine, we must bring along "metaphysical commitments to God's omnipotence." A key feature of process philosophy and theology is that God truly exists as a compassionate and luring presence within the universe and within each human heart, that this luring presence transcends the universe as a cosmic Self with feelings and aims of its own, and that this Self is all-loving but not all-powerful. See, for example, Rabbi Bradley Artson's God Almighty? No Way!

Perhaps it goes without saying that this process way of thinking is itself antithetical to many and perhaps all Traditionalist sensibilities. A denial of omnipotence, traditionally understood, seems like a denial of God. But for process thinkers the denial is religiously meaningful, because it makes space for believing in a truly compassionate God who does not will violence, murder, rape, cruelty, and our current wholesale assault on a small but beautiful planet. Process thinkers believe that God's luring presence is powerful, but in a way that requires creaturely cooperation for its fulfillment. In the tradition of Modernity, they want to affirm a certain kind of creativity that is as real in its way, as is God's in God's way. Hence their affirmation of co-creativity. This best makes sense if we distinguish between Ultimate Reality and Ultimate Actuality, not unlike the way that Whitehead distinguishes between Creativity and the Primordial Nature of God.

Morningstar writes:

Just as, for Christians, it was the Divine Will of God which demanded that Jesus Christ be crucified and enter Hell so that sin and death could be conquered, I believe there’s a certain Divine Wisdom in the death Modernity has brought to organized religion and even God himself...When Jesus subsequently rose from the dead following his crucifixion, he was unrecognizable to his followers. So too will the resurrection of the existing religions following Modernity involve fundamental shifts, but these shifts will not be breaks from the Divine Will, but rather its fulfillment.

To my mind, these sentences give rise to the idea of a non-dual Ultimate Reality (with capital letters) that is manifest, expressed or revealed in all that happens in the world, including (1) the rise of modernity and its dethroning of religion and (2) tragic events such as the crucifixion of Jesus. It is as if Ultimate Reality has agency of its own and that all things are expressions of its will.

Whitehead wrestled with this question and arrived at two provocative ideas. The first is that, all things considered, it is best to deny Ultimate Reality this kind of agency and better to think that it (Ultimate Reality) is actual in virtue of its instances. The second is that there is a cosmic soul of the universe, God, who is continuously at work in the universe and who is the primordial but not exclusive expression of ultimate reality. Here is how he puts it in Process and Reality:

In all philosophic theory there is an ultimate which is actual in virtue of its accidents. It is only then capable of characterization through its accidental embodiments, and apart from these accidents is devoid of [11] actuality. In the philosophy of organism this ultimate is termed ‘creativity’; and God is its primordial, non-temporal accident.* In monistic philosophies, Spinoza's or absolute idealism, this ultimate is God, who is also equivalently termed ‘The Absolute.’ In such monistic schemes, the ultimate is illegitimately allowed a final, ‘eminent’ reality, beyond that ascribed to any of its accidents. In this general position the philosophy of organism seems to approximate more to some strains of Indian, or Chinese,thought, than to western Asiatic, or European, thought. One side makes process ultimate; the other side makes fact ultimate.

The upshot of this way of thinking is to say that ultimate reality is not an agent with a will of its own, but rather an unnamable depth which is manifest, expressed, and revealed in all things that have agency: God on the one hand, and finite creatures (quantum events, living cells, plants, and animals) on the other. God is that particular instance of creativity which beckons creatures toward creative expressions of their own creativity and absorbs their influence with tender care. God is powerful, but not all powerful. Things happen in the world which even God cannot prevent.

On this view, neither the rise of Modernity nor the crucifixion of Jesus can be conceived as a pure expression of God's will. Both are an outcome, at least in part, of the self-creativity of ultimate reality. They happen on their own. And yet both can also be conceived, at least in part, as responses to the will of God. After all, at a certain point in his life, God called Jesus to die on the cross, despite Jesus' own leanings to the contrary: "not my will but thy will, O Lord." Jesus aligned his own agency with God's will. And so, at this stage in history, might we humans do the same, whether we are Traditionalists or Constructive Postmodernists, or some blend. Our task at this time may well be to help usher into the world something new, with traces of tradition, traces of modernity, and traces of a future not contained by Tradition or Modernity (however conceived and related). This may be the great work: not to make gods of the past, traditional or modern, but to listen and respond to a call from Beyond, a Beyond that comes to us, not as a spatial hierarchy resting in the sky, but as a dream to be realized, belonging both to God and to us, in partnership.

- Jay McDaniel, 12/7/2021