A Southerner Reflects

On Her Racist Heritage

Lee McAuliffe Rambo

Writer’s Note: The following began as a reply to a question put to me by a fellow participant in the recent Probing Process and Reality with John Cobb course conducted by Tripp Fuller of Homebrewed Christianity. But it quickly grew into a reflection -- inspired, no doubt, by our nation’s observance of Juneteenth.

I am not sufficiently versed (or interested) in the technical aspects of Whitehead’s cosmology to address your “prehension” issue. I undertook my studies at Claremont not as an intellectual exercise but to render intelligible my spiritual sensibilities and several incidents of what William James called “religious experience.” Although never conventionally religious, my quest was very much in keeping with the classic notion that theology is “faith seeking understanding.”

So, I must offer you a nontechnical response that is heavy on general description and personal experience. Whitehead did hold that the past is past; our experiences, whether tragic or joyful, become immortally ingredient in the consequent nature of God. Our ineradicable conviction that our lives are worthwhile is grounded in our intuitive grasp that we are in fact contributing to the life of God. At the same time, God draws on this memory bank to generate the aims for intensity and harmony that are relevant to the continuing life of the cosmos (and our own puny lives). This is redemption.

As you know, the Whiteheadian cosmology is based on analogia entis: only like can know like. God’s constitution (with the obvious except of divine immortality) is ours writ large. If this were not so, all our language about God would meaningless.

As both common sense and psychology affirm, trauma at a vulnerable developmental stage can affect a person’s trajectory for life. To cope with the practical demands of living, we First-World humans often suppress or repress the memory of the original assault – but that memory can be quickened when one undergoes a similar experience. That happened to me at age 29, when I returned to the States after three years in France and landed in the very inhospitable Union Theological Seminary. I had a full-blown “delayed grief reaction” in which I mourned every disappointment and loss I had ever experienced.

It should go without saying that my black brothers and sisters, when confronted with contemporary violence, also relive the traumas they and their loved ones have suffered previously. (For just this reason, there is a movement among activists to suppress graphic media coverage of violence against blacks. I don’t agree. As a journalist, I am inspired by Ida B. Wells, the black investigative reporter who exposed the atrocity of lynching in the 1890s.)

I also know this to be true because, in 1985, as communications officer for the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, I accompanied many of the original activists as we reenacted the march from Selma to Montgomery. As we crossed the Edmund Pettus Bridge -- where police had fractured John Lewis’ skull and turned dogs and firehoses on peaceful protestors -- middle-aged people wept.

You ask if black Americans also experience the trauma of their enslaved ancestors? Evidence is emerging that trauma is indeed embedded in the genetic code and passed onto progeny – a literal transmission of the “sins of the fathers.” This is very plausible to me, an Irish American whose family has had more than its fair share of alcoholism. Many process academics are open to the insights offered by the Hindu and Buddhist doctrines of reincarnation, and I am as well.

But, for me, the test of any theological theory is its practical application. That is, to be valid, a theology must not only exhibit internal consistency and coherence but also conform to experience, from the mundane to the extraordinary, and render life intelligible if not luminous.

Process theology does this for me to the extent that I emulate God’s redemptive action, facing past evils squarely, repenting, and moving toward an unprecedented harmony. As a white Southerner from the ruling class, I embrace my guilt to the degree that it motivates me; I strive to use my privilege as a platform for examining and combatting racism.

I also try to celebrate the life-affirming aspects of the culture that I share with black Southerners: closeness to the land; the pleasures of cooking, eating and socializing; a sense of time that is not regulated by the clock; an appreciation of family and intimate friendships; love of language and story-telling; hospitality and courtesy; emotional expression, particularly in church; and a delight in eccentric personalities.

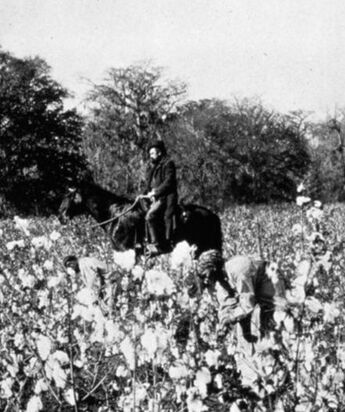

When my mother died, there wasn’t much of value to pass on. But she left me a little wood chair that had been crafted by an unknown person in bondage to my ancestors. For years it had been on the back porch of my great-grandfather’s house in south Georgia; generations of cooks, enslaved and nominally freed, sat in it to shell peas and beans and shuck corn for my forebears. Because of their uncompensated labor, the Colonel became a wealthy man who could afford to send my grandmother and all four of her sisters to college before the First World War.

That little nail-less chair now hangs on the wall of the study where I write and tutor. It is a constant reminder that I have benefited incalculably from the oppression of the black race. It is a constant reminder that I must dedicate my life to redeeming the unspeakable sins of my fathers.

I am not sufficiently versed (or interested) in the technical aspects of Whitehead’s cosmology to address your “prehension” issue. I undertook my studies at Claremont not as an intellectual exercise but to render intelligible my spiritual sensibilities and several incidents of what William James called “religious experience.” Although never conventionally religious, my quest was very much in keeping with the classic notion that theology is “faith seeking understanding.”

So, I must offer you a nontechnical response that is heavy on general description and personal experience. Whitehead did hold that the past is past; our experiences, whether tragic or joyful, become immortally ingredient in the consequent nature of God. Our ineradicable conviction that our lives are worthwhile is grounded in our intuitive grasp that we are in fact contributing to the life of God. At the same time, God draws on this memory bank to generate the aims for intensity and harmony that are relevant to the continuing life of the cosmos (and our own puny lives). This is redemption.

As you know, the Whiteheadian cosmology is based on analogia entis: only like can know like. God’s constitution (with the obvious except of divine immortality) is ours writ large. If this were not so, all our language about God would meaningless.

As both common sense and psychology affirm, trauma at a vulnerable developmental stage can affect a person’s trajectory for life. To cope with the practical demands of living, we First-World humans often suppress or repress the memory of the original assault – but that memory can be quickened when one undergoes a similar experience. That happened to me at age 29, when I returned to the States after three years in France and landed in the very inhospitable Union Theological Seminary. I had a full-blown “delayed grief reaction” in which I mourned every disappointment and loss I had ever experienced.

It should go without saying that my black brothers and sisters, when confronted with contemporary violence, also relive the traumas they and their loved ones have suffered previously. (For just this reason, there is a movement among activists to suppress graphic media coverage of violence against blacks. I don’t agree. As a journalist, I am inspired by Ida B. Wells, the black investigative reporter who exposed the atrocity of lynching in the 1890s.)

I also know this to be true because, in 1985, as communications officer for the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, I accompanied many of the original activists as we reenacted the march from Selma to Montgomery. As we crossed the Edmund Pettus Bridge -- where police had fractured John Lewis’ skull and turned dogs and firehoses on peaceful protestors -- middle-aged people wept.

You ask if black Americans also experience the trauma of their enslaved ancestors? Evidence is emerging that trauma is indeed embedded in the genetic code and passed onto progeny – a literal transmission of the “sins of the fathers.” This is very plausible to me, an Irish American whose family has had more than its fair share of alcoholism. Many process academics are open to the insights offered by the Hindu and Buddhist doctrines of reincarnation, and I am as well.

But, for me, the test of any theological theory is its practical application. That is, to be valid, a theology must not only exhibit internal consistency and coherence but also conform to experience, from the mundane to the extraordinary, and render life intelligible if not luminous.

Process theology does this for me to the extent that I emulate God’s redemptive action, facing past evils squarely, repenting, and moving toward an unprecedented harmony. As a white Southerner from the ruling class, I embrace my guilt to the degree that it motivates me; I strive to use my privilege as a platform for examining and combatting racism.

I also try to celebrate the life-affirming aspects of the culture that I share with black Southerners: closeness to the land; the pleasures of cooking, eating and socializing; a sense of time that is not regulated by the clock; an appreciation of family and intimate friendships; love of language and story-telling; hospitality and courtesy; emotional expression, particularly in church; and a delight in eccentric personalities.

When my mother died, there wasn’t much of value to pass on. But she left me a little wood chair that had been crafted by an unknown person in bondage to my ancestors. For years it had been on the back porch of my great-grandfather’s house in south Georgia; generations of cooks, enslaved and nominally freed, sat in it to shell peas and beans and shuck corn for my forebears. Because of their uncompensated labor, the Colonel became a wealthy man who could afford to send my grandmother and all four of her sisters to college before the First World War.

That little nail-less chair now hangs on the wall of the study where I write and tutor. It is a constant reminder that I have benefited incalculably from the oppression of the black race. It is a constant reminder that I must dedicate my life to redeeming the unspeakable sins of my fathers.