- Home

- Process Worldview

- Community

- Art and Music

- Whitehead and Process Thinking

- Podcasts

- Spirituality

- Ecological Civilization

- Education

- Contact

- Social Justice

- Science

- Animals

- Sacred Poems

- Whitehead Videos

- Index of All Titles

- Practicing Process Thought

- Process Spirituality: A Spiritual Alphabet

- Recent Posts

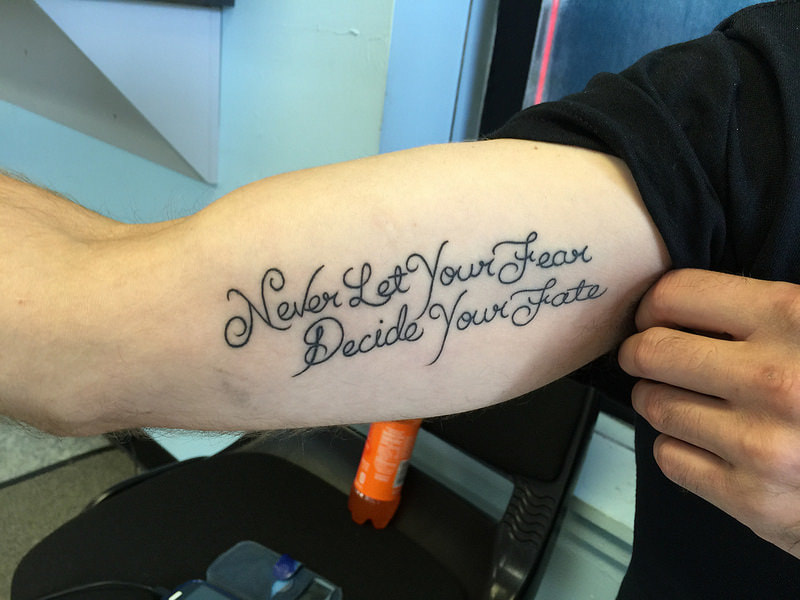

A Tattoo of the Heart

by Teri Daily

|

My senior year in seminary at Austin, our class decided to get tattoos. Well, actually, it had been talked about and in the planning stages ever since orientation that very first August, in 2005. Throughout our time together, discussions about tattoo design permeated the usual seminary talk about papers, exams, chapel, ordination, and placement. Drawings of possible designs were posted in the library. And by Christmas of 2007, there was consensus about what the Episcopal Theological Seminary of the Southwest Class of 2008 tattoo would look like. It was to be a two-dimensional illustration of the seminary cross which stood in the courtyard just outside the chapel. The cross was the most recognizable feature on campus, so although not original, it just made sense that would be the image.

My friend Edson took on the job of finding a tattoo parlor in Austin that was exemplary in the areas of hygiene and artistry. The winning parlor was run by a man we’ll just call John. After seeing my friend arrive on a Harley Davidson sporting leather pants and a minister’s collar, John decided that he may need to check out the Episcopal Church. (In the words of my friend Edson, score one for Jesus and the Anglican Communion…) The place was sparkling clean, and the tattoo artist, who we’ll call Cathy, was said to be both experienced and “real spiritual.” Everything seemed to be going according to plan. Shortly after the General Ordination Exams in January (the exams we have to take before we can be ordained), the first wave of Seminary of the Southwest Class of 2008 students hit the tattoo parlor. It was exciting, there was a lot of energy and a real sense of belonging, and I wanted to be a part of it. One by one my friends would return from the tattoo parlor—beautiful images of the cross customized for each one of them according to the color of their skin, the size of the area the tattoo would cover, and personal preference. But somehow I couldn’t bring myself to get the tattoo. Sure, pain was an issue, but I had given birth without medication and so thought I could handle the pain of a tattoo. If I was worried about what people might think, I could put it in a spot that was almost never visible. And I loved these people—they were like family. So what was the problem then? Of course there’s the whole issue of how the tattoo would age as my own skin aged and changed—those of you who have seen the Saturday Night Live skit know what I mean. But what really stopped me was the requirement to commit whole-heartedly in a way that’s permanent and irrevocable. I mean, what if the seminary came to be a very different place over the next 50 years, so that the symbol of that particular cross represented something very different from what it encompassed at the moment of my graduation? And what if one of these wonderful people that I loved very much did something a little crazy down the road—would I want to be forever associated with them? What if I looked back on my seminary experience over time only to remember the difficult things that were a part of that journey—would I want to be forever reminded of painful memories every time I looked at that tattoo? The bottom line: I wasn’t ready to commit in a permanent, irrevocable way. I treasure my freedom too much for that. I like to keep all of my options open. And that brings me a passage at the end of the book of Jeremiah. The people of Judah haven’t kept the covenant God handed down to Moses on Mount Sinai—they haven’t kept the Law. Their temple lies in ruins, and their king along with many of the elite citizens of Judah has been carried off to Babylon. At this point Jeremiah’s words are no longer those of judgment; they’ve become words of hope. He speaks now of a time when God will make a new covenant with God’s people—one that the house of Israel will no longer have to struggle to fulfill, failing time and time again. For this time God will tattoo the Law on their very hearts in a permanent and irrevocable way. God will transform them starting on the inside, in such a way that they will know the Lord and follow the ways of God. It’s a beautiful picture Jeremiah paints: “I will put my law within them, and I will write it on their hearts; and I will be their God, and they shall be my people. No longer shall they teach one another, or say to each other, ‘Know the Lord,’ for they shall all know me, from the least of them to the greatest, says the Lord; for I will forgive their iniquity, and remember their sin no more” (Jeremiah 31:33-34, NRSV). I think it’s the one of the most beautiful descriptions of our total belonging to God that we see in the Bible. The Church has projected onto this passage an understanding of Christ living in us, transforming us and bringing us into the very life of God. But when we read these words it’s impossible not to come face to face with the fact that this kind of belonging that we hear about in Jeremiah has yet to be made perfect in our own lives. We still struggle with wanting our freedom, with wanting the right to choose when and in what way we will give ourselves to God. I suspect that Jesus’ disciples knew what that felt like, too. As they journey to Jerusalem with Jesus, Jesus speaks of his coming death. And then, of course, comes the kicker. He says: “If any want to become my followers, let them deny themselves and take up their cross and follow me.” Belonging to Jesus seems to come with a cost, with a loss of freedom. We experience this a little bit in the season of Lent; we often describe the practices we take on as sacrifices. Lent’s a time when we give things up, from chocolate to beer to Facebook. And we see ourselves as giving up our freedom in the name of devotion. But discipleship isn’t about limiting our freedom; it’s about giving up the things in this world that we think will bring us freedom and, instead, focusing on that which truly does. Let’s face it, there are many false ways we seek to secure our own freedom. We believe that the more options we have and the more money with which to purchase them, the freer we are. We think that having power—be it in the form of prestige, physical dominance, or occupying top rung on the professional ladder—we think that having such power is a source of freedom. We even occasionally think that avoiding relationships with those who might call us out of our comfort zone and into places we’d rather not go is a way to preserve our freedom. But the truth is that in our attempts to remain in control of our lives and to grasp freedom through choice and power, we lose the very thing we’re looking for. We’re not free; instead, we become slaves to material wealth, to what others think of us, and to the fear of not being in control. We’ve got our whole definition of what freedom is all wrong. The disciplines of Lent are really to remind us that freedom isn’t about being in control or having power or getting to choose. Real freedom comes when our love for God determines what we do, instead of our fear. It comes from knowing the love of God tattooed irrevocably in our hearts, calling us to places and to tasks that we never thought would be life-giving, but that are. And so as we come to the final days of Lent and turn our eyes toward Jerusalem, may God transform our hearts, giving us the grace and courage to follow Jesus. And may we find our true freedom in him. |