- Home

- Process Worldview

- Community

- Art and Music

- Whitehead and Process Thinking

- Podcasts

- Spirituality

- Ecological Civilization

- Education

- Contact

- Social Justice

- Science

- Animals

- Sacred Poems

- Whitehead Videos

- Index of All Titles

- Practicing Process Thought

- Process Spirituality: A Spiritual Alphabet

- Recent Posts

A Whole Universe of Stories

Patricia Adams Farmer

"We are in the midst of seismic cultural change. In the old paradigm, priorities are shaped by a mechanistic worldview that privileges whatever can be numbered, measured, and weighed; human beings are pressured to adapt to the terms set by their own creations. Macroeconomics, geopolitics, and capital are glorified. . . . In the new paradigm, culture is given its true value. The movements of money and armies may receive close attention from politicians and media voices, but at ground-level, we care most about human stories, one life at a time.” ---Arlene Goldbard, The Culture of Possibility: Art, Artists, and the Future

GROWING UP THROUGH THE CRACKS of the broken worldview we call modernity are verdant shoots we call stories—human stories built of words and images and feelings and connected threads of subjective experience. We see them everywhere, not only in film and literature, but in the daily lives of regular people telling their own stories about where they come from and what makes them happy or sad, about people they love and animals that make them laugh or weep. About what makes life meaningful.

These are the messy, imperfect bursts of life that modernity views with suspicion. After all, stories lack “objectivity” and precision; they can’t be tested and measured—-or trusted. Unless stories can be marketed for big profits, they are devalued and walked over without a thought. But they just keep shooting up through the cracks—all these human stories on the internet, in faith communities, in murals and memoir and songs—living, fresh, personal stories that don’t quite jive with a mechanistic worldview.

And along with the spurting up of verdant stories comes a little Cosmic Irony. For all our modern advances, a sustainable future may depend on what we have left behind long ago: the stories and myths that birthed us into being. We need to replant ourselves in stories as we move into a new, organic stage of human consciousness—one that just might save the day in the eleventh hour of our questionable future on planet Earth.

Stories circle back to the past, to ancient peoples, story-tellers and shamans who told their hair-raising and comedic tales of creation around warming fires—or painted their stories on damp, cool cave walls. Stories in sacred texts are like this, too. But sacred texts are old and cracked like cave paintings, and not many people pay attention to them anymore. But as constructive postmodernists, we do pay attention. We have to. We need to read, listen, watch, and feel the stories all around us, for stories teach us about empathy and connect us to the world and to God and to God's body, the earth.

All our stories—written, spoken, sung, painted, danced—come from way down deep, from an ancient place, an organic and healing place. In the beginning, our stories are the sparks flung out from the primordial fireball itself. Like our expanding universe, these are the ongoing stories of the world, of people and frogs and trees and floods and revolutions and love and war, and even species extinction. We need them—all of them, no matter how sad or how insignificant they may seem. For in an organic world, a process world, all stories matter.

Our stories matter because we live in a narrative universe. In a philosophy of organism, the worldview of Alfred North Whitehead, stories make up everything. Stories begin with experience and are shot through with feeling. They inherit from the past and contribute to the future. They have a beginning, a middle, an ending; they become and perish, and yet live for evermore in the eternal unfolding of new stories. In this way stories are through and through organic, relational, always in process, and never quite finished. Even in God, Whitehead would say, tragic stories are creatively transformed from mere wreckage to “tragic beauty.” In this way, stories become another word for hope.

The entire universe consists of stories within stories within stories—within stories! As Jay McDaniel says, “People have their stories; animals have their stories; plants have their stories; the earth has its story; stars have their stories; and heaven has its story, too. Sometimes the stories are pleasant and sometimes painful. Often they are both and always they intersect. We are storied into existence by the stories of others.”

We could say that the world, instead of being made of “turtles all the way down,” is made of stories all the way down. But if we think of stories as frameworks for human meaning, we can also say that stories go all the way up! A child’s life is a story that finds meaning in the story of a family, which finds meaning in the story of community, which finds meaning in the story of global community, which finds meaning in the cosmological stories of the universe. Stories go all the way up to the sky and journey through the stars and planets and galaxies. We are storytellers; we are meaning-makers.

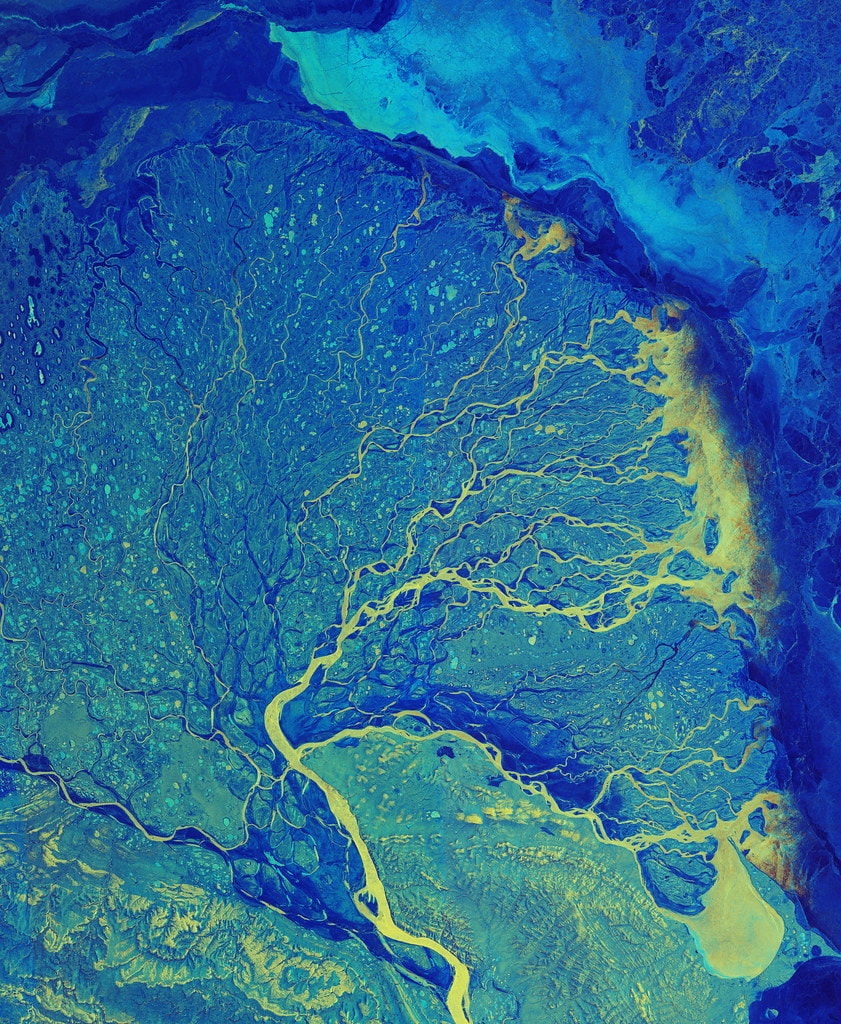

And so the ancient storytellers and shamans rise up within our collective memory, and we tell our stories of personal and communal and religious and cosmic experience. We see ourselves within the stories that are trees and stories that are rivers and stories that are lady bugs and stories that are seeds. We do this, as did our ancestors, because stories nurture meaning and ecological community and psychic wholeness. Each tiny story matters, for it is part of the larger cosmological story, each story adding to the beauty of God. Within this sacred universe of stories, we find our place among the stars and rocks and snowy egrets. We find something of beauty; we find our significance.

GROWING UP THROUGH THE CRACKS of the broken worldview we call modernity are verdant shoots we call stories—human stories built of words and images and feelings and connected threads of subjective experience. We see them everywhere, not only in film and literature, but in the daily lives of regular people telling their own stories about where they come from and what makes them happy or sad, about people they love and animals that make them laugh or weep. About what makes life meaningful.

These are the messy, imperfect bursts of life that modernity views with suspicion. After all, stories lack “objectivity” and precision; they can’t be tested and measured—-or trusted. Unless stories can be marketed for big profits, they are devalued and walked over without a thought. But they just keep shooting up through the cracks—all these human stories on the internet, in faith communities, in murals and memoir and songs—living, fresh, personal stories that don’t quite jive with a mechanistic worldview.

And along with the spurting up of verdant stories comes a little Cosmic Irony. For all our modern advances, a sustainable future may depend on what we have left behind long ago: the stories and myths that birthed us into being. We need to replant ourselves in stories as we move into a new, organic stage of human consciousness—one that just might save the day in the eleventh hour of our questionable future on planet Earth.

Stories circle back to the past, to ancient peoples, story-tellers and shamans who told their hair-raising and comedic tales of creation around warming fires—or painted their stories on damp, cool cave walls. Stories in sacred texts are like this, too. But sacred texts are old and cracked like cave paintings, and not many people pay attention to them anymore. But as constructive postmodernists, we do pay attention. We have to. We need to read, listen, watch, and feel the stories all around us, for stories teach us about empathy and connect us to the world and to God and to God's body, the earth.

All our stories—written, spoken, sung, painted, danced—come from way down deep, from an ancient place, an organic and healing place. In the beginning, our stories are the sparks flung out from the primordial fireball itself. Like our expanding universe, these are the ongoing stories of the world, of people and frogs and trees and floods and revolutions and love and war, and even species extinction. We need them—all of them, no matter how sad or how insignificant they may seem. For in an organic world, a process world, all stories matter.

Our stories matter because we live in a narrative universe. In a philosophy of organism, the worldview of Alfred North Whitehead, stories make up everything. Stories begin with experience and are shot through with feeling. They inherit from the past and contribute to the future. They have a beginning, a middle, an ending; they become and perish, and yet live for evermore in the eternal unfolding of new stories. In this way stories are through and through organic, relational, always in process, and never quite finished. Even in God, Whitehead would say, tragic stories are creatively transformed from mere wreckage to “tragic beauty.” In this way, stories become another word for hope.

The entire universe consists of stories within stories within stories—within stories! As Jay McDaniel says, “People have their stories; animals have their stories; plants have their stories; the earth has its story; stars have their stories; and heaven has its story, too. Sometimes the stories are pleasant and sometimes painful. Often they are both and always they intersect. We are storied into existence by the stories of others.”

We could say that the world, instead of being made of “turtles all the way down,” is made of stories all the way down. But if we think of stories as frameworks for human meaning, we can also say that stories go all the way up! A child’s life is a story that finds meaning in the story of a family, which finds meaning in the story of community, which finds meaning in the story of global community, which finds meaning in the cosmological stories of the universe. Stories go all the way up to the sky and journey through the stars and planets and galaxies. We are storytellers; we are meaning-makers.

And so the ancient storytellers and shamans rise up within our collective memory, and we tell our stories of personal and communal and religious and cosmic experience. We see ourselves within the stories that are trees and stories that are rivers and stories that are lady bugs and stories that are seeds. We do this, as did our ancestors, because stories nurture meaning and ecological community and psychic wholeness. Each tiny story matters, for it is part of the larger cosmological story, each story adding to the beauty of God. Within this sacred universe of stories, we find our place among the stars and rocks and snowy egrets. We find something of beauty; we find our significance.