- Home

- Process Worldview

- Community

- Art and Music

- Whitehead and Process Thinking

- Podcasts

- Spirituality

- Ecological Civilization

- Education

- Contact

- Social Justice

- Science

- Animals

- Sacred Poems

- Whitehead Videos

- Index of All Titles

- Practicing Process Thought

- Process Spirituality: A Spiritual Alphabet

- Recent Posts

Alfred North Whitehead’s

Artistic Cosmos *

J. R. Hustwit

Methodist University

Fayetteville, NC, USA

In the United States, the arts are in crisis. In most states, public funding for arts education for children has been reduced to nearly nothing over the past 30 years. Many primary schools have no arts program, or one art teacher to be shared among 3 or 4 schools. At the same time, most universities struggle to defend the importance of their art departments, as fewer and fewer student pursue degrees in art. Many students and their parents feel that studying art is incompatible with earning money or having a stable career. I suspect that at least most of us here, however, agree that art is a valuable vocation, both to society and to the individual. I offer a philosophical proposition that art is not only useful, but that art is the metaphysical foundation for all human and non-human social activity.

In the 1920’s and 1930’s, Anglo-American philosopher Alfred North Whitehead used his extensive knowledge of science, logic, and mathematics to propose a model of reality—a metaphysics—that radically departed from the popular philosophy of his time. Whitehead suggested that the universe is not composed of substances moving through space, but rather all beings are composed of momentary events. This requires a radical re-orientation in the way we think, so if you need a moment or two to adjust, I understand. He called his metaphysics a “philosophy of organism,” though his thinking later came to be known as “process philosophy.”

In Whitehead’s process philosophy, the ultimate material cause of all things is creativity. Creativity is the principle of novelty by which the many events in the past come to be unified in a new feeling.[1] So, imagine we live in a universe of momentary events, and each of us is a rapid series of events. There are electron events, molecular events, animal events, and human events. Each event is a very very brief throb of feeling. Your life is a series of momentary throbs of feeling, each informed by the previous moment. Each “actual occasion,” as he calls these events, feels the events of the past, selects those feelings that are relevant, and combines them into a new complex feeling, which will be felt by all future events.[2] This is the rhythm of creativity. To feel the past, recombine those feelings in a novel way, and then to stand as a public fact for others to interpret. Reality is a massive, interconnected process, composed of countless sparks of creativity. While other philosophers assume that creativity is an anomaly found only in conscious humans, Whitehead supposes that the human experience of creativity is emblematic of the rest of the cosmos.

The process of feeling, selecting, combining, and expressing scales all the way up from atomic events to human civilizations. When the artist feels the feelings of the world, and combines them into a new expression for others to feel, that is a human manifestation of the universe’s fundamental rhythm—a process of unfolding creativity. If Whitehead is right, or even close to right, then art (painting, performance, sculpture, writing, and so on) is not something that humans have invented. It is not an exceptional act that separates us from the rest of nature. Rather, it is the most fundamental activity of nature. Art, I suggest, is the most basic function of the cosmos, and all beings, regardless of size and complexity, have creativity built in at the atomic level. In fact, all beings are manifestations of creativity. Creating art is what every actual occasion in the universe already does at every moment.

We may then ask, if every being is an artist, and art is created without any effort, why go to art college? Why take lessons? Why not just look to nature, which is itself creative expression at every moment in every place? The answer is that skill is needed to make that creativity relevant to other humans. Only beings with complex consciousness can produce works of art that speak to other conscious beings. A sunset is beautiful, but it “dwarfs humanity. . . a million sunsets will not spur on men toward civilization. It requires Art to evoke into consciousness the finite perfections which lie ready for human achievement.”[3] Nature itself is too big to be meaningful to humans. Artists are needed to select, refine, and adapt truths of the cosmos into forms that will speak to other humans. This takes skill, sensitivity, and training—education.

We may also ask what exactly makes a work of art effective. I cannot claim to know firsthand. I do not possess much artistic sensitivity myself. But Whitehead argues that the point of art is the production of beauty and truth in some combination.[4] He defines beauty as a mathematician might: it is a function of patterned contrasts in a supporting harmony.[5] But it is not enough for art to be beautiful. It must also express truth, which happens when an appearance is adapted to match a reality. Beauty without truth “is on a lower level, with a defect of massiveness.” Like a cliché, it is pleasing but shallow. Likewise, truth without beauty is trivial. “Truth matters because of beauty.”[6] We can all imagine an artless memorandum from the office. It may be true, but it is boring and forgettable. Both truth and beauty are important for art to have a meaningful impact upon other humans.

If we take Whitehead’s philosophy seriously—and I do—then we see there are two messages for artists. First, art is fundamental to the cosmos. The very fabric of reality is an artistic process, and human art is just one manifestation of the most basic activity of reality. Second, societal change is impossible without art. Only the combination of truth and beauty in artistic expression can inspire other humans to see the world as it is, to think new thoughts, to feel new feelings, and to imagine better possibilities for the way we live. Whitehead’s metaphysics is highly speculative. Many philosophers will disagree with its premises. I have no desire to defend its technical details. But I offer it as an imaginative possibility, or a hypothetical model. The universe may not be a dead and cold empty space in which humans are, with respect to their art, isolated and disjoined. Instead, I invite you to imagine that the very fabric of reality is artistic, and that creativity is the activity that precedes and makes possible all other human achievements, whether economic, scientific, or political. In this light, art is not just worthy of our esteem and respect, but indispensable to every person’s education.

Works Cited

Whitehead, Alfred North. Adventures of Ideas. New York: The Free Press. 1967.

______. Process and Reality. Corrected edition. Edited by Donald W. Sherburne and David Ray Griffin. New York: The Free Press. 1978.

[1] Alfred North Whitehead, Process and Reality, corrected edition, edited by Donald W. Sherburne and David Ray Griffin (New York: The Free Press, 1978), 21.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Whitehead, Adventures of Ideas (New York: The Free Press, 1967), 271.

[4] Ibid., 267-270.

[5] Ibid., 267.

[6] Ibid., 267.

* This essay was originally published in Ajanta: An International Multidisciplinary Research Journal, Volume X, Issue 1, January-March, 2021, and is republished with permission from J.R. Hustwit

Learning from our Ancestors:

Two Lessons from Cave Art

"Nature itself is too big to be meaningful to humans. Artists are needed to select, refine, and adapt truths of the cosmos into forms that will speak to other humans. This takes skill, sensitivity, and training—education." (J.R. Hustwit)

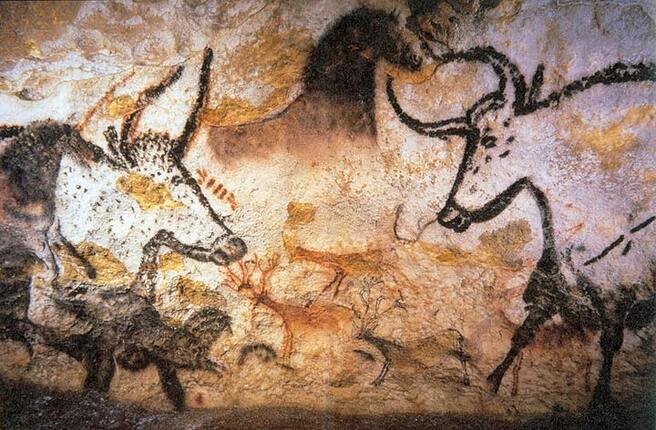

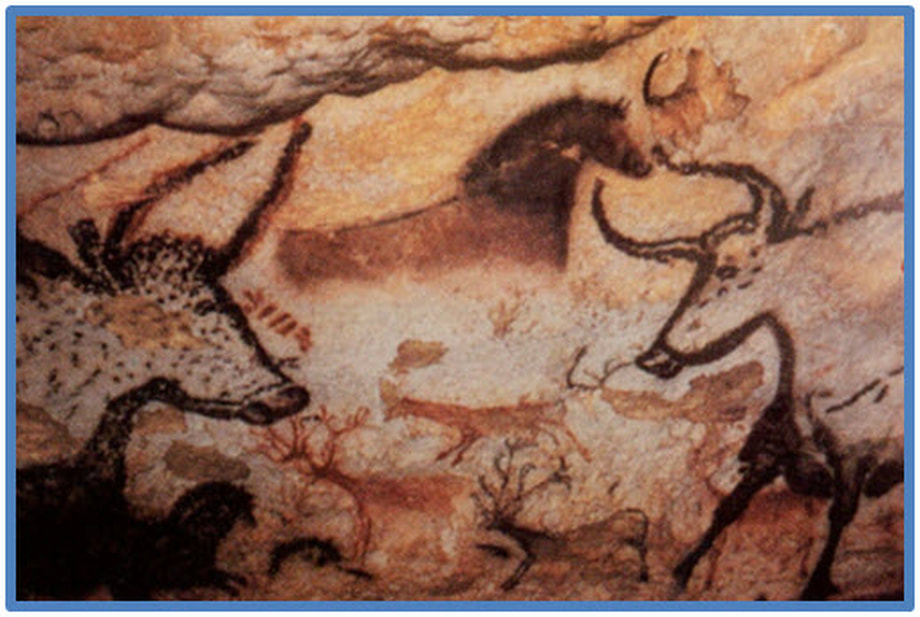

In order to appreciate Whitehead’s artistic cosmos, it helps to reflect upon the art of early humans and Neanderthals. The art was almost always about Nature, mostly animals in the paleolithic period. From the BBC discussion of cave art offered below by Melvyn Bragg and scholars, we learn two things: (1) that humans and human-like creatures have been artistic from their very beginnings and (2) that art is not reducible to a narrow and European understanding of “the aesthetic.”

By a narrow and European understanding of the aesthetic, I have in mind the idea that all visual art is to framed, placed in galleries, and gazed upon by detached observers, without having any practical function in everyday life or needs for survival. Very little art around the world has been “aesthetic” in this sense. Instead, it has been an act of creating something new, whether abstract or figurative out of the world that is given to experience, and integrating the novel production into the many other influences that influence a life: social, physical, emotional, religious, economic. Once created, art becomes part of “the many” that “become one” in the experiences of those who come later.

And so it is for the cosmos itself as it creates new things over time, again and again. As J.R. Hustwitt puts it, we may well live in an artistic cosmos.

The universe may not be a dead and cold empty space in which humans are, with respect to their art, isolated and disjoined. Instead, I invite you to imagine that the very fabric of reality is artistic, and that creativity is the activity that precedes and makes possible all other human achievements, whether economic, scientific, or political. In this light, art is not just worthy of our esteem and respect, but indispensable to every person’s education.

The primordial art is the universe itself and each creature there-within, creating something new. The secondary art is the art we humans create which selects from what is given from Nature for the sake of "meaning."

Who educated the cave artists? Who taught them? We don't know. But Hustwitt's point is well taken: educating in the arts may be one way of participating in a larger creativity that includes other animals, the earth, stars, planets, the universe. And if the unity of the universe is itself, as Whitehead suggests, a living reality with a soul of its own, otherwise called the Poet of the universe, then creativity is part of that poet's life, too.

- Jay McDaniel

In order to appreciate Whitehead’s artistic cosmos, it helps to reflect upon the art of early humans and Neanderthals. The art was almost always about Nature, mostly animals in the paleolithic period. From the BBC discussion of cave art offered below by Melvyn Bragg and scholars, we learn two things: (1) that humans and human-like creatures have been artistic from their very beginnings and (2) that art is not reducible to a narrow and European understanding of “the aesthetic.”

By a narrow and European understanding of the aesthetic, I have in mind the idea that all visual art is to framed, placed in galleries, and gazed upon by detached observers, without having any practical function in everyday life or needs for survival. Very little art around the world has been “aesthetic” in this sense. Instead, it has been an act of creating something new, whether abstract or figurative out of the world that is given to experience, and integrating the novel production into the many other influences that influence a life: social, physical, emotional, religious, economic. Once created, art becomes part of “the many” that “become one” in the experiences of those who come later.

And so it is for the cosmos itself as it creates new things over time, again and again. As J.R. Hustwitt puts it, we may well live in an artistic cosmos.

The universe may not be a dead and cold empty space in which humans are, with respect to their art, isolated and disjoined. Instead, I invite you to imagine that the very fabric of reality is artistic, and that creativity is the activity that precedes and makes possible all other human achievements, whether economic, scientific, or political. In this light, art is not just worthy of our esteem and respect, but indispensable to every person’s education.

The primordial art is the universe itself and each creature there-within, creating something new. The secondary art is the art we humans create which selects from what is given from Nature for the sake of "meaning."

Who educated the cave artists? Who taught them? We don't know. But Hustwitt's point is well taken: educating in the arts may be one way of participating in a larger creativity that includes other animals, the earth, stars, planets, the universe. And if the unity of the universe is itself, as Whitehead suggests, a living reality with a soul of its own, otherwise called the Poet of the universe, then creativity is part of that poet's life, too.

- Jay McDaniel

Cave Art

A BBC Discussion

Melvyn Bragg of the BBC and guests discuss ideas about the Stone Age people who created the extraordinary images found in caves around the world, from hand outlines to abstract symbols to the multicoloured paintings of prey animals at Chauvet and, as shown above, at Lascaux. In the 19th Century, it was assumed that only humans could have made these, as Neanderthals would have lacked the skills or imagination, but new tests suggest otherwise. How were the images created, were they meant to be for private viewing or public spaces, and what might their purposes have been? And, if Neanderthals were capable of creative work, in what ways were they different from humans? What might it have been like to experience the paintings, so far from natural light? With Alistair Pike, Professor of Archaeological Sciences at the University of Southampton; Chantal Conneller, Senior Lecturer in Early Pre-History at Newcastle University; and Paul Pettitt, Professor of Palaeolithic Archaeology at Durham University. Producer: Simon Tillotson.

READING LIST:

Norbert Aujoulat, The Splendour of Lascaux: Rediscovering the Greatest Treasure of Prehistoric Art (Thames and Hudson, 2005) Paul G. Bahn, Journey through the Ice Age (W&N, 1997)

Paul G. Bahn, Cave Art: A Guide to the Decorated Ice Age Caves of Europe (Frances Lincoln, 2012)

Paul G. Bahn, Images of the Ice Age (Oxford University Press, 2016)

Jean Clottes, What is Palaeolithic Art?: Cave Paintings and the Dawn of Human Creativity (University of Chicago Press, 2016)

Jean Clottes and David Lewis-Williams, The Shamans of Prehistory: Trance and Magic in the Painted Caves (Harry N. Abrams, 1998) Bruno David, Cave Art (Thames and Hudson, 2017)

David Lewis-Williams, The Mind in the Cave: Consciousness and the Origins of Art (Thames and Hudson, 2004)

READING LIST:

Norbert Aujoulat, The Splendour of Lascaux: Rediscovering the Greatest Treasure of Prehistoric Art (Thames and Hudson, 2005) Paul G. Bahn, Journey through the Ice Age (W&N, 1997)

Paul G. Bahn, Cave Art: A Guide to the Decorated Ice Age Caves of Europe (Frances Lincoln, 2012)

Paul G. Bahn, Images of the Ice Age (Oxford University Press, 2016)

Jean Clottes, What is Palaeolithic Art?: Cave Paintings and the Dawn of Human Creativity (University of Chicago Press, 2016)

Jean Clottes and David Lewis-Williams, The Shamans of Prehistory: Trance and Magic in the Painted Caves (Harry N. Abrams, 1998) Bruno David, Cave Art (Thames and Hudson, 2017)

David Lewis-Williams, The Mind in the Cave: Consciousness and the Origins of Art (Thames and Hudson, 2004)