America the Ugly, Too

Our History of Slavery and

Rapacious Businessmen

an interview with a Yale historian of Slavery David Blight on 12 Years a Slave,

the trailer from the film, a short quotation from Frederic and Mary Ann Brussat,

and a theological reflection by Reverend Teri Daily and Jay McDaniel

|

|

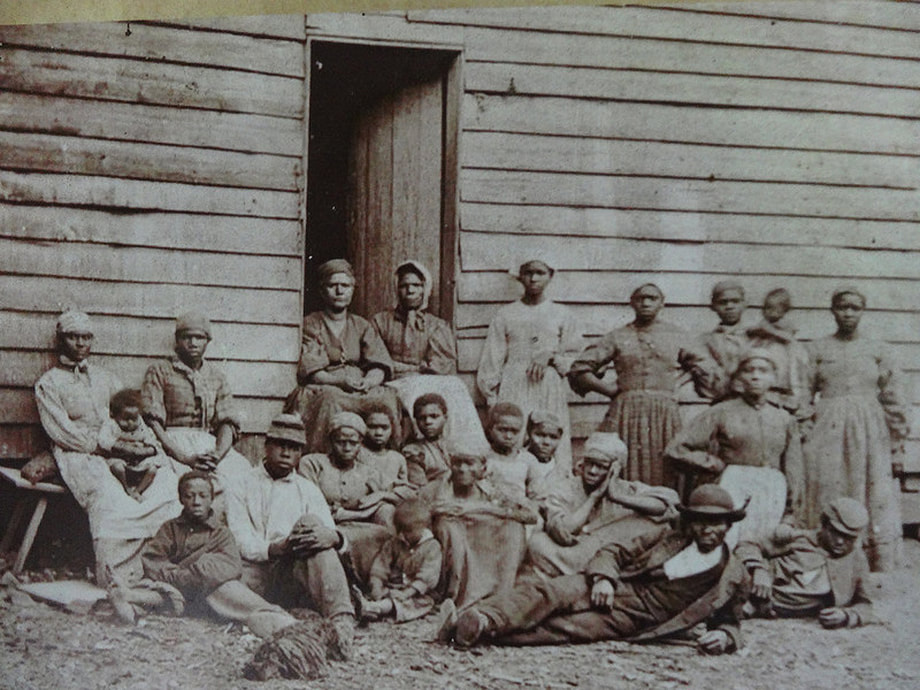

Rapacious business men seeing slaves as property, societal attitudes that blacks are subhuman, and the resulting abrogation of human and civil rights for slaves."

-- Frederic and Mary Ann Brussat, Excerpt from Review of 12 Years a Slave in Spirituality and Practice |

So often these two forms of hiding go together. When we hide from the worst of our history, we are hiding from a future that is more honest and humane, humble and just. By reminding us of our past, historians like David Blight help open us into toward more promising futures. We move from triumphalism into the very place God always calls us: creative transformation for the sake of healthy community, in the context of which the will of God is done on earth as it is in heaven. |

Never look directly into the sun. A common refrain, especially when the time of a solar eclipse draws near. And so we take cardboard with a pinhole in it and project the image of the sun onto another sheet of paper. It is just safer to look at some things indirectly—something the human psyche learned a long time ago. That is why the setting for the Book of Daniel is the Babylonian exile, even though it was written some 300 years later to speak to the Jewish people during the crisis known as the Maccabean revolt. That is why the popular TV show M*A*S*H portrays a mobile hospital unit during the Korean War, even as it served as a society’s reflection on the Vietnam War, a war still in progress when the series began. That is why we in the US look to Germany as the case study for societal sin passed down to subsequent generations, instead of looking a little further back in our very own history at the sin of slavery that still casts it shadow on our nation. It seems that distance, be it temporal or geographical or cultural, makes it safer to look unflinchingly at difficult realities.

But the problem with avoiding the truth of our history is that, as David Blight makes clear, redemption can only come after honesty. Those of us who live in the United States, especially if we are among the middle-class and privileged, are notorious for always wanting to paint a pretty picture of who "we" have been, as if our history has been one of unending progress. We find it hard to be honest about our sins. And certainly this includes the sin of slavery, understanding that our country was built on slavery and that we once had the biggest slave system on the planet.

We would do much better to learn from the authors of the Hebrew Bible who, in wanting to tell the story of their history, included stories of fully human beings who were morally fallible and sometimes did atrocious things. Think of Solomon and David. Israel was not built by saints. The story of Israel is not one of unending progress, but of morally ambiguous zig-zagging. And so it is with most of us, individually and collectively.

What to do? Well, if there is truly a spirit of creative transformation at work in the world, redeeming and transforming us into a more compassionate and creative people, this spirit can best work if, in the beginning, we are honest about our sins, including our history of slavery. Because once we’re honest about the evil that has been done, the suffering that has been caused, and the ways in which we have benefitted, then we can begin to respond in ways that are redemptive. These responses are included in what John Swinton in his book Raging with Compassion[1] calls redemptive practices that embody the Church’s response to evil and suffering, although, in reality, these practices can be embraced by people of all faiths and by those who claim no religious affiliation.

First, we can listen to the laments of our enslaved brothers and sisters, to their cries of grief, anger, and despair. In the spirit of honesty, we must confess that we have not often enough listened, or even wanted to listen, to the stories of our enslaved sisters and brothers. We want to relegate them to the past when in fact they are, and always will be, objectively immortal in our nation and its memories. If our lives unfold in a cloud of witnesses, they are themselves among the witnesses of who we are and always will be. Terry Gross and David Blight speak, in the interview above, of setting aside a day to remember those slaves whose histories are inevitably linked with ours. Perhaps this day would be not just a day of remembering, but also a day of listening.

Second, we can practice thoughtfulness, or intentionality. We tend to think that atrocities such as slavery (which often entail violent beatings, the separation of family members, and the rape of females slaves) arise out of extraordinary evil—a capacity for, and type of, evil that far outstrips that evil which you and I recognize in ourselves. But the truth is that small, very ordinary acts of evil can, over time and in large number, lead to unimaginable evil, tragedy, and suffering.

In other words, as Swinton would rightly point out, there is no qualitative difference between the evil that exists in each of us and the evil that was present in the plantation owners of the nineteenth century. And while that may at first sound like a frightening assertion, there is also incredible hope here. Because if great evil can be caused by small, ordinary acts of evil, then intentional, small acts of thoughtfulness can prevent the recurrence of such atrocities and perhaps even, in some way and over time, redeem that great evil which is woven into our history. Thoughtful self-reflection and an intentional awareness of the world around us can enable us to recognize evil in ourselves and in the world, and to make choices that lead to greater wholeness.

Finally, we can practice true hospitality. Such hospitality is not merely about creating spaces that seem welcoming or acts that make someone feel comfortable, although these are important aspects of hospitality. But radical hospitality is a disposition of the heart; it approaches the stranger from a position of openness and trust. In this way, we are freed from prejudice and overwhelming fear—both of which form the basis of much evil in the world today. And we are free to form redemptive friendships that recognize the “sacred” in each of us.

It may seem like we can do these things quite apart from cultural and political transformation, but the truth is that we cannot. A genuine repentance -- a genuine turning around from our history of slavery -- requires that each of us turn our energies toward the common good. Culturally, our need is to move beyond the cult of individualism which permeates our society into a concern for community well-being of all. It is time to recognize that we are not egos-in-isolation but rather persons-in-community. We are not, and never have been, separable from other members of the human family, including those we victimize.

Politically, our need is support public policies which enable the emergence of local communities that are creative, compassionate, participatory, multicultural, and ecologically wise, with no one left behind. In our time we speak of these communities as sustainable communities. They are sustaining because they live within the limits of the earth to absorb wastes and supply nourishment for life, but also because they sustain meaningful human relationships that do not hide from the past or hide from the future.

So often these two forms of hiding go together. When we hide from the worst of our history, we are hiding from a future that is more honest and humane, humble and just. By reminding us of our past, historians like David Blight help open us into toward more promising futures. We move from triumphalism into the very place God always calls us: creative transformation for the sake of healthy community, in the context of which the will of God is done on earth as it is in heaven.

[1] John Swinton, Raging with Compassion, (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2007).

But the problem with avoiding the truth of our history is that, as David Blight makes clear, redemption can only come after honesty. Those of us who live in the United States, especially if we are among the middle-class and privileged, are notorious for always wanting to paint a pretty picture of who "we" have been, as if our history has been one of unending progress. We find it hard to be honest about our sins. And certainly this includes the sin of slavery, understanding that our country was built on slavery and that we once had the biggest slave system on the planet.

We would do much better to learn from the authors of the Hebrew Bible who, in wanting to tell the story of their history, included stories of fully human beings who were morally fallible and sometimes did atrocious things. Think of Solomon and David. Israel was not built by saints. The story of Israel is not one of unending progress, but of morally ambiguous zig-zagging. And so it is with most of us, individually and collectively.

What to do? Well, if there is truly a spirit of creative transformation at work in the world, redeeming and transforming us into a more compassionate and creative people, this spirit can best work if, in the beginning, we are honest about our sins, including our history of slavery. Because once we’re honest about the evil that has been done, the suffering that has been caused, and the ways in which we have benefitted, then we can begin to respond in ways that are redemptive. These responses are included in what John Swinton in his book Raging with Compassion[1] calls redemptive practices that embody the Church’s response to evil and suffering, although, in reality, these practices can be embraced by people of all faiths and by those who claim no religious affiliation.

First, we can listen to the laments of our enslaved brothers and sisters, to their cries of grief, anger, and despair. In the spirit of honesty, we must confess that we have not often enough listened, or even wanted to listen, to the stories of our enslaved sisters and brothers. We want to relegate them to the past when in fact they are, and always will be, objectively immortal in our nation and its memories. If our lives unfold in a cloud of witnesses, they are themselves among the witnesses of who we are and always will be. Terry Gross and David Blight speak, in the interview above, of setting aside a day to remember those slaves whose histories are inevitably linked with ours. Perhaps this day would be not just a day of remembering, but also a day of listening.

Second, we can practice thoughtfulness, or intentionality. We tend to think that atrocities such as slavery (which often entail violent beatings, the separation of family members, and the rape of females slaves) arise out of extraordinary evil—a capacity for, and type of, evil that far outstrips that evil which you and I recognize in ourselves. But the truth is that small, very ordinary acts of evil can, over time and in large number, lead to unimaginable evil, tragedy, and suffering.

In other words, as Swinton would rightly point out, there is no qualitative difference between the evil that exists in each of us and the evil that was present in the plantation owners of the nineteenth century. And while that may at first sound like a frightening assertion, there is also incredible hope here. Because if great evil can be caused by small, ordinary acts of evil, then intentional, small acts of thoughtfulness can prevent the recurrence of such atrocities and perhaps even, in some way and over time, redeem that great evil which is woven into our history. Thoughtful self-reflection and an intentional awareness of the world around us can enable us to recognize evil in ourselves and in the world, and to make choices that lead to greater wholeness.

Finally, we can practice true hospitality. Such hospitality is not merely about creating spaces that seem welcoming or acts that make someone feel comfortable, although these are important aspects of hospitality. But radical hospitality is a disposition of the heart; it approaches the stranger from a position of openness and trust. In this way, we are freed from prejudice and overwhelming fear—both of which form the basis of much evil in the world today. And we are free to form redemptive friendships that recognize the “sacred” in each of us.

It may seem like we can do these things quite apart from cultural and political transformation, but the truth is that we cannot. A genuine repentance -- a genuine turning around from our history of slavery -- requires that each of us turn our energies toward the common good. Culturally, our need is to move beyond the cult of individualism which permeates our society into a concern for community well-being of all. It is time to recognize that we are not egos-in-isolation but rather persons-in-community. We are not, and never have been, separable from other members of the human family, including those we victimize.

Politically, our need is support public policies which enable the emergence of local communities that are creative, compassionate, participatory, multicultural, and ecologically wise, with no one left behind. In our time we speak of these communities as sustainable communities. They are sustaining because they live within the limits of the earth to absorb wastes and supply nourishment for life, but also because they sustain meaningful human relationships that do not hide from the past or hide from the future.

So often these two forms of hiding go together. When we hide from the worst of our history, we are hiding from a future that is more honest and humane, humble and just. By reminding us of our past, historians like David Blight help open us into toward more promising futures. We move from triumphalism into the very place God always calls us: creative transformation for the sake of healthy community, in the context of which the will of God is done on earth as it is in heaven.

[1] John Swinton, Raging with Compassion, (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2007).