- Home

- Process Worldview

- Community

- Art and Music

- Whitehead and Process Thinking

- Podcasts

- Spirituality

- Ecological Civilization

- Education

- Contact

- Social Justice

- Science

- Animals

- Sacred Poems

- Whitehead Videos

- Index of All Titles

- Practicing Process Thought

- Process Spirituality: A Spiritual Alphabet

- Recent Posts

Question to John Cobb (posed after Sept. 11, 2001)

Does process theology have anything to say about patriotism?

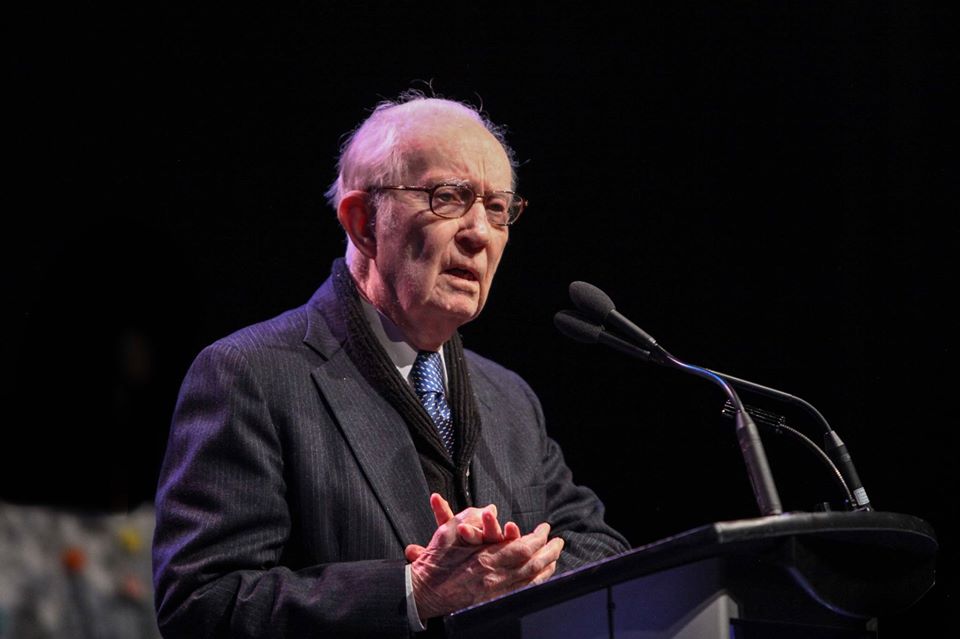

John Cobb's Response

We are surrounded by a great resurgence of patriotism. My neighbors have had a flag out ever since September 11. Knowing them, I do not doubt that it expresses a healthy love of our country. But there are good reasons for Christians to worry that patriotism passes over too easily, and too commonly, into a religious nationalism that is unacceptable. There seems to be a lot of that around. Does the process perspective throw any helpful light on this?

Process theology has two implications that at first blush seem to be in considerable tension. On the one hand, it strongly encourages us to view the world as we believe God views it. From that perspective all creatures are important and among them human beings are especially important. Human beings in one culture or nation are not more important than those in other cultures and nations. Further, all are interconnected. It is the whole that should command our loyalty and concern.

From this point of view, we could view nations as necessary evils which should in time be superseded by global unification and government. We could argue that caring more for the people in one nation than for those in others is a violation of our deeper duty. If we reason in this way, it seems that patriotism is misdirected loyalty, a form of idolatry.

The second implication cuts in a different direction. Although we are in relation with all other creatures, the relations with our nearer neighbors are of far greater importance than those with remote creatures. Our responsibilities are correlative with this importance. That is, we can make a much greater difference in the lives of those who are most closely related to us than in the lives of those who are remote. If we tried to care equally for all children, our own children would suffer terribly. If everyone cared equally for all children, all children would suffer terribly. Viewing matters from this perspective, special love of our own country makes sense as an extension of special love for those with whom we are most closely connected.

For process theology it is important to hold both sets of implications. Furthermore, it is not enough to hold them in tension with one another. We aim at coherent thought. We need a vision of the world under God that does justice to both sets of implications. And that is not as difficult as it may seem.

Whitehead sees the world as made up of individual occasions of experience. Some of these have no stable patterns of relations, and these make up empty space. The creatures in which we take primary interest are organized into societies. The organs of the human body, such as hearts, kidneys, livers, and brains, are societies, and the primary character and role of the member occasions is shaped by participation in the society. When some cells cease to participate positively in the societies of which they are members, cancer may occur. The health and well being of the organs contribute to that of the body as a whole and depend on the health and wellbeing of the body as a whole.

The relations among people have important analogies to those among the organs in a single body. As the human body is a society of societies, so also we can think of human families as societies of societies of societies, and of larger grouping of human beings as societies of societies of societies of societies -- and so forth,. A nation is one of these more inclusive societies. The whole of creatioin is a much more inclusive society of societies . . . . When any subsociety acts without regard for the wellbeing of the larger society of which it is a member, the result is analogous to that of cancer in the human body.

Of course, the analogy has limits. One limitation is that human beings have capacities that individual cells do not. We can be aware not only of the most immediate societies to which we belong but of the larger societies of societies as well. It is possible for children to be indoctrinated to subordinate their loyalty to family to that to the nation. Jesus called for a loyalty to his movement that subordinated loyalty to family. A globalist may ask us to subordinate all lesser loyalties to that to the whole. Human capacities for transcendence make possible such top-down patterns, and no doubt there are times and places where they are needed.

From the perspective of process theology, however, the subordination of loyalty to the more intimate society to the more inclusive one is not normally desirable. The whole is normally better served by healthy sub-societies. A nation in which parents fear that their children will betray them, is not a healthy nation. When family relations are broken by the conversion of individual members to a new religious community, much of value is lost.

On the other hand, if members of a family forget that the family is a member of larger societies, both the larger society and the family suffer. The deeper wellbeing of a family depends on being part of a flourishing larger society. It is to the long-term interest of the family to contribute positively to that larger society even at the expense of its short-term desires. Hence each member of the family should seek to shape the family both for its own immediate well being and so as to contribute to the wider society. Prior to September 11, the problem seemed more an indifference to the well being of the nation as a whole than excessive concern about it.

The wider society exists at many levels and takes many forms. For the past several centuries the most important of these forms has been the nation state. Because of its real importance, it deserves special loyalty from the individual persons and the societies that make it up. On the other hand, the concentration of power and loyalty at the level of the nation state has had many negative consequences. The state has often demanded that "patriotism" supersede loyalties to the many societies of which it is composed and block loyalty to any larger society. When it does that, process theology must protest. The nation is but one society of societies and a member of a larger society. It has greater claim on the loyalty of those who live within it than does any other nation. But it deserves that superior loyalty only as it participates responsibly in the larger family of nations.

When the nation fails to participate responsibly in the larger family, especially when it acts in ways that are deeply harmful to others and to the larger whole, love of nation requires efforts to change its behavior and, as a minimum, to protest. True patriotism will say that "I love my country right or wrong." It does not say that I will obey the national leadership "right or wrong." When one believes that one's national policies are irresponsible and destructive, true patriotism expresses itself in calling for repentance for one's nation's sins and doing what one can to direct the nation's activity in the right channels. For those who believe in God, it calls for reminding the nation that God cares equally for other peoples and respects their love of their nations.

My own view is that the right direction today is to surrender some of the powers that have been concentrated at the national level to local communities and others to international bodies such as the United Nations and the World Court. But the real danger currently is that we surrender national power to transnational corporations and the global institutions that encourage their dominance. Hence, in the whole complex process of finding the right checks and balances, I find myself supporting patriotism as a provisional check on transforming power from political to economic actors. I also find myself allied to nationalists in their opposition to economic globalism. On the other hand, I oppose nationalists when they seem to believe that we have the right to inflict unlimited suffering on others if that preserves our own national security. In doing all this, I believe I am being patriotic, that is, expressing my love for country in a way that process theology encourages.

A Different Kind of Patriotism

Commentary by Jay McDaniel

Imagine that the universe lives and moves and has its being in the context of a larger and inclusive life; and imagine further that this life, God, is truly and essentially loving: affected by all that happens, sharing in suffering and joy, and seeking the well-being of each and all. This is the God in whom open and relational theologians believe.

We do not think that God is all-powerful in the sense of being able to coerce the world into conformity with God's aims. But we do think that God is continuously present in the world and in human life as guiding and animating spirit.

This guiding and animating spirit need not be identified with religion. If you feel within your heart a desire to help create communities that are creative, compassionate, participatory, inclusive, multicultural, humane to animals, and good for the earth, you are feeling what open and relational thinkers understand as the quiet, guidance of God. You do not need to name the desire "God" in order to feel it and respond to it.

Many of us who trust in this kind of God feel a tension between being loyal to the world and loyal to one's nation. The tension lies not only in the people but in God.

On the one hand God loves all people equally. God is not an ethnic or religious nationalist. God is not Jewish or Christian or Muslim or Hindu, American or Chinese or Russian or Brazilian. God is all of these things and none of these things. On the other hand, God seeks to promote richness of experience and human the flourishing of life in bonded communities, both national and local. God is not interested in the each as well as the all: that is, the local flourishing of life as well as the general flourishing.

Love of Country

We may well experience God's seeking within ourselves as a call to a certain kind of patriotism: a love of our country and our local community. This is not a patriotism that excludes people who live in other nations; it is patriotism that seeks their well-being, too, and that encourages them to be, in this sense, patriotic.

John Cobb feels called toward this kind of patriotism and proposes in the note below that process theology likewise leads to this kind of patriotism.

For John Cobb this has practical, political implications. In the note below he supports:

These first policy will be controversial to ethnic and religious nationalists who emphasize national sovereignty over all things. The second two will be controversial to globalists who believe that economic integration is a key to world peace and prosperity. Cobb's view, developed over many years, is that all three are important for the well-being of life on earth and that, today, all should be understood in the larger context of helping build a world that is a community of communities of communities, where the earth itself is understood, not simply as an issue among issues but a context for all issues. He and other process thinkers speak of this aspirational ideal as Ecological Civilization, the local instantiations of which are the kinds of communities described above.

* Cobb's note on patriotism was originally published in Process and Faith (December 2001) just after the events of September 11 in the United States and is republished with permission.

Commentary by Jay McDaniel

Imagine that the universe lives and moves and has its being in the context of a larger and inclusive life; and imagine further that this life, God, is truly and essentially loving: affected by all that happens, sharing in suffering and joy, and seeking the well-being of each and all. This is the God in whom open and relational theologians believe.

We do not think that God is all-powerful in the sense of being able to coerce the world into conformity with God's aims. But we do think that God is continuously present in the world and in human life as guiding and animating spirit.

This guiding and animating spirit need not be identified with religion. If you feel within your heart a desire to help create communities that are creative, compassionate, participatory, inclusive, multicultural, humane to animals, and good for the earth, you are feeling what open and relational thinkers understand as the quiet, guidance of God. You do not need to name the desire "God" in order to feel it and respond to it.

Many of us who trust in this kind of God feel a tension between being loyal to the world and loyal to one's nation. The tension lies not only in the people but in God.

On the one hand God loves all people equally. God is not an ethnic or religious nationalist. God is not Jewish or Christian or Muslim or Hindu, American or Chinese or Russian or Brazilian. God is all of these things and none of these things. On the other hand, God seeks to promote richness of experience and human the flourishing of life in bonded communities, both national and local. God is not interested in the each as well as the all: that is, the local flourishing of life as well as the general flourishing.

Love of Country

We may well experience God's seeking within ourselves as a call to a certain kind of patriotism: a love of our country and our local community. This is not a patriotism that excludes people who live in other nations; it is patriotism that seeks their well-being, too, and that encourages them to be, in this sense, patriotic.

John Cobb feels called toward this kind of patriotism and proposes in the note below that process theology likewise leads to this kind of patriotism.

For John Cobb this has practical, political implications. In the note below he supports:

- transferring some powers now concentrated in nations to international organizations such as the United Nations and World Court: internationalism.

- transferring some powers now concentrated in nations to local communities: communitarianism.

- transferring economic powers from global entities to nations themselves: economic nationalism.

These first policy will be controversial to ethnic and religious nationalists who emphasize national sovereignty over all things. The second two will be controversial to globalists who believe that economic integration is a key to world peace and prosperity. Cobb's view, developed over many years, is that all three are important for the well-being of life on earth and that, today, all should be understood in the larger context of helping build a world that is a community of communities of communities, where the earth itself is understood, not simply as an issue among issues but a context for all issues. He and other process thinkers speak of this aspirational ideal as Ecological Civilization, the local instantiations of which are the kinds of communities described above.

* Cobb's note on patriotism was originally published in Process and Faith (December 2001) just after the events of September 11 in the United States and is republished with permission.