- Home

- Process Worldview

- Community

- Art and Music

- Whitehead and Process Thinking

- Podcasts

- Spirituality

- Ecological Civilization

- Education

- Contact

- Social Justice

- Science

- Animals

- Sacred Poems

- Whitehead Videos

- Index of All Titles

- Practicing Process Thought

- Process Spirituality: A Spiritual Alphabet

- Recent Posts

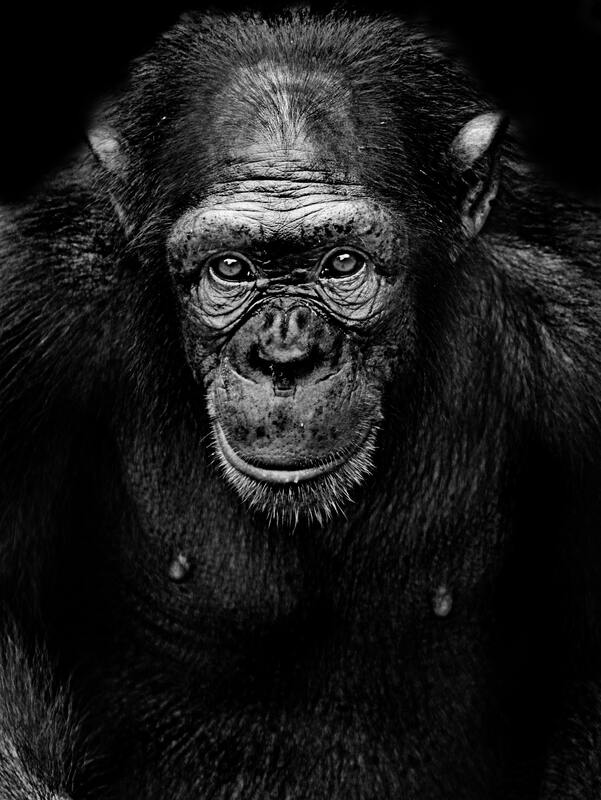

Editor's Note: The process movement (see Process Nexus) is devoted to the creation of communities that are creative, compassionate, participatory, diverse, inclusive, humane to animals, and good for the Earth, with no one left behind. These communities are the building blocks of what we call "ecological civilizations." Being humane to animals includes, of course, compassionate treatment: protecting animals from abuse, providing space for them to enjoy their unique forms of satisfaction. But it also includes a sense of kinship with them: that is, a recognition that they, like us, are subjects of their own lives, with experiences of their own, that are valuable to them and beautiful in their own right. Animals inspire awe, wonder, and a sense of connection. For the religiously-minded, such respect entails a twofold recognition: (1) that the cosmic Soul of the universe, God, is within animals an inwardly felt lure to live with satisfaction relative to the situation at hand and (2) that animal experiences add richness to the divine life that would not be present otherwise. In short, the cosmic Soul feels their feelings and is enriched by what is felt, quite apart from human life. God would not be "God" without the animals.

Of course, human beings are animals, too. We and other animals are all "creatures of the flesh," to use biblical language. The use of the word "animal" to refer to non-human beings is a concession to popular parlance, even as it suggests a dualistic cosmology that is problematic. The bottom line, however, is that other animals enjoy and suffer aesthetic experiences, forms of consciousness, and forms of thinking that are worthy of respect and admiration. In the essay below, Susan Armstrong-Buck, shows how Whitehead's philosophy can help us appreciate "non-human" experience. The article appeared in Process Studies, pp. 1-18, Vol. 18, Number 1, Spring, 1989. Process Studies is published quarterly by the Center for Process Studies, 1325 N. College Ave., Claremont, CA 91711. Used by permission. This material was prepared for Religion Online by Ted and Winnie Brock and is republished with permission from Religion Online.

- Jay McDaniel, November 4, 2021

Of course, human beings are animals, too. We and other animals are all "creatures of the flesh," to use biblical language. The use of the word "animal" to refer to non-human beings is a concession to popular parlance, even as it suggests a dualistic cosmology that is problematic. The bottom line, however, is that other animals enjoy and suffer aesthetic experiences, forms of consciousness, and forms of thinking that are worthy of respect and admiration. In the essay below, Susan Armstrong-Buck, shows how Whitehead's philosophy can help us appreciate "non-human" experience. The article appeared in Process Studies, pp. 1-18, Vol. 18, Number 1, Spring, 1989. Process Studies is published quarterly by the Center for Process Studies, 1325 N. College Ave., Claremont, CA 91711. Used by permission. This material was prepared for Religion Online by Ted and Winnie Brock and is republished with permission from Religion Online.

- Jay McDaniel, November 4, 2021

Non-Human Experience: A Whiteheadian Analysis

by Susan Armstrong-Buck

In opposition to many Western epistemologies, Whitehead maintains that most experience is not conscious, that language, while crucial to thought, is not essential to it, and that feeling is the fundamental mode of disclosure of the world (PR 36/54). Whitehead also has a strongly empirical side, expressed in his insistence that a system of metaphysical ideas must be both "applicable" and "adequate" with regard to experience (PR 4-5/6-8). Accordingly, the aim of this paper is to make an application of Whitehead’s system to recent findings concerning nonhuman experience, in particular primate experience. I will argue that Whitehead’s system can easily accommodate the new findings. I will also attempt to demonstrate that in some respects animal consciousness is closer to human consciousness than Whitehead had reason to believe.

In the process of this application it will be necessary to attempt an account of self-consciousness consistent with Whitehead’s system. While Whitehead’s writings are rich in the systematic description of consciousness per se, he does not use the term "self-consciousness" systematically and mentions it only once in Process and Reality (107/164).1 In the attempt to obtain clarity in this regard I propose we consider self-consciousness to be a subjective form characterized by higher and more complex contrasts2 than exhibited by consciousness per se. In addition, I propose that we distinguish four types of self-consciousness: agent, public, introspective and pure. I will argue that three of these types of self-consciousness are clearly exhibited by language-using primates and quite probably by many other animals. Pure self-consciousness, however, seems to be an achievement rare even for human beings.

Understanding Nonhuman Beings. Whitehead’s distinction between two modes of perception is a highly useful one in evaluating past and present research designs concerned with animal experience. In the twentieth century, such research has relied almost exclusively on perception in the mode of presentational immediacy, that is, on quantified sense data devoid of a sense of past inheritance and thus devoid of meaning, emotion or purpose. It is apparent that perception in this mode does not disclose mental functioning. Whitehead’s system allows us to come to terms with this situation, since perception in the mode of causal efficacy involves the prehension of the outcome of both the mental and physical poles of the concretum3 as well as the subjective form, the "feel" of individual experience (insofar as it can be felt by a subsequent concrescence). Thus vague though powerful emotions and intuitions need no longer be ruled out as merely subjective and hence irrelevant, unscientific responses to the data.

It is of course true that careful observation requires the use of controls, the elimination of the possibility of social cuing, guarding against uncritical projection of the observer’s prejudices and presuppositions, etc. (MA 83-98). But increasingly researchers in this field are coming to agree that careful observation also requires an acknowledgement of the emotion, meaning and purpose in nonhuman experience. Attention to our intuitive and feelingful sense of our connections with the surrounding world, including other animals, is necessary in order to make correct interpretations.

Konrad Lorenz states:

Nobody can assess the mental qualities of a dog without having once possessed the love of one, and the same thing applies to many other intelligent socially living animals, such as ravens, jackdaws, large parrots, wild geese and monkeys. (MMD 162)

More recently, Menzel has observed that "we need very much to develop and refine methods which explicitly recognize and exploit, rather than attempt to eliminate, the observer’s prescientific, intuitive and global forms of judgment" (GDMP 303).

De Waal and colleagues have been testing human intuition concerning the behavior of chimps at the Arnheim Zoo since 1976. He states, "that the same testing principle was independently proposed by Menzel is illustrative of the new Zeitgeist" (DNCC 224). He adds that the scientists unwilling to attribute intentionality to animals are generally those with little direct experience with the behavior of nonhuman primates (DNCC 221). De Waal has found that short-term predictions of aggressive behavior based on the subjective evaluation of the personality, mood and frustrations of the chimps were much more reliable than estimations based on objective categorizations and explicit rules (that is, on quantitative and sensory-based criteria). De Waal points out that the basis of such intuitions is difficult to convey to others, due to the subtleties of primate interactions. The "look in the eye" of a primate can convey whether or not the action was intentional (DNCC 222)

Nohuman Aesthetic and Moral Experience. Whitehead asserts that animals experience emotions, hopes and purposes, largely derived from bodily functions, and yet "tinged to a degree with conceptual functioning" (MT 37). "The animals enjoy structure: they can build nests and dams: they can follow the trail of scent through the forest" (MT 104). Observations unknown to Whitehead offer striking examples of the ability of some animals to enjoy sensuous contrasts and structures for their own sakes. Birds offer many of the best examples. Bowerbirds, a family of passerine birds which live in the rain forests of Australia and New Guinea, build bowers laid out so that the sun will not blind the bird while he dances in the presence of the female. The bowers have a display ground decorated with colored objects, chosen with great care as to their color and form (BB 42, 47-51). Some birds paint the walls of their bowers with fruit pulp, wet powdered charcoal, or a paste of chewed-up grass mixed with saliva. The satin bowerbird uses a wad of bark with which to apply the paint; the bower painting varies greatly among individual birds, regardless of their color or maturity (BR 37-9).

Bird song has given aesthetic pleasure to human beings for untold years. Does it also give aesthetic pleasure to birds? It appears so. Joan Hall-Craig states of blackbird songs that "the constructional basis appears to be identical to that which we find in our own music." There is rhythmic impulse and recoil in the organization of motifs and matching of tonal and temporal patterns to form symmetrical wholes (BV 375-6). To human ears, the aesthetic value of a bird song suffers when the bird must become practical and repel an intruder or attract a mate (ANHN 105-31). Charles Hartshorne has devoted much trained attention to bird song and argues that song requires "something like an aesthetic sense in the animal," though it may be more a matter of aesthetic feeling rather than aesthetic thought (BS 2, 12).

Whitehead attributes morality to the higher animals, in addition to their enjoyment of form. By this he seems to mean that animals exhibit a sense of foresight and self-transcendence. Along the same lines, Sapontzis argues that animals’ intentional and sincere, kind and courageous actions are moral actions, for they accord with accepted moral norms, and we do not require demonstrations of moral principle in everyday human moral practice (AAMB 51-2).

By understanding morality in this way, we can find abundant examples of moral actions. For example, mutual aid has been observed in 130 different species of birds (NT 167). Burton, an experienced ethologist, states that animals are capable of compassion, pity, sympathy, affection and grief, as well as true altruism (JLA 91). Rachels has described an experiment with rhesus monkeys in which not only did monkeys refrain from eating for many days in order not to shock another monkey, but the willingness to undergo such hunger was correlated with (1) whether or not the monkeys had been cagemates and (2) whether or not the hungry monkey had itself been in the situation of the monkey undergoing the shocks. Thus the altruistic behavior was directly related to the vividness of the empathy felt by the hungry monkey (DARL 215-6). We should also note the many instances of intra and inter-species helping behavior exhibited by dolphins (MW 166-68). Whitehead recognizes such animal goodness in a memorable passage:

Without doubt the higher animals entertain notions, hopes and fears. And yet they lack civilization by reason of the deficient generality of their mental functioning. Their love, their devotion, their beauty of performance, rightly claim our love and our tenderness in return. Civilization is more than all these; and in moral worth it can be less than all these. (MT 5, emphasis added)

Symbolic Reference. Whitehead distinguishes human beings from animals on the basis of different capacities for the inhibition of symbolic reference. The inhibition of symbolic reference frees the conceptual element as exemplified in presentational immediacy from its exemplification in causal efficacy and thus frees the symbol to carry meanings other than those conveyed by the immediate past (ME 80; S 6, 83f).

Pigeons have been shown to be capable of a degree of inhibition of symbolic reference (SCTW 372). But more surprisingly, the displaced qualities of the "dance language" of honeybees involve some degree of inhibition of symbolic reference. This dance language was discovered by the brilliant experiments of Karl von Frisch in the 1930’s, but unfortunately Whitehead makes no reference to it. One astonishing discovery is that the waggle dance tells the direction to the food source in relation to the position of the sun (AT 179). The waggle dance communicates the direction, distance and desirability of a distant object. Lindauer has studied the waggle dances involved in swarming, in which the colony establishes itself in a new cavity. The process occurs over several days in which various workers visit and dance about the distance, direction, and desirability of several different cavities. Remarkably, when several individually marked bees were observed, a dancer sometimes changed from being a communicator to being a recipient. "She would stop dancing about her own discovery and follow dances by one of her more enthusiastic sisters. After following several such dances, she would visit the new cavity and begin dancing about it, with the appropriate change in vigor as well as her indication of distance and direction" (AT 183). Bees have also been observed to anticipate where food sources provided by experimenters will be when the source is moved varying distances according to a fixed mathematical formula (DHK 69f).

Many scientists have difficulty accepting these results because of their belief that the "wiring" of bees is too simple to allow such feats. Whitehead’s system is able to encompass the results, however: while the actual occasions constituting the central nervous system of bees are certainly of a lower degree of complexity than that of mammals, a bee brain contains thousands of interactive neurons, so that there is no a priori reason why the dominant occasion of the bee may not be capable of complex experiences in situations relevant to the bees’ survival. Exactly how many neurons are necessary for conscious thinking is unknown. Learning is now known to be well within the capacity of many annelids, mollusks, and anthropods (AT 173-76). It appears then that the idea of invertebrates as prewired machines is an inadequate interpretation of the data and that bees enjoy not only ‘conformal propositions’ but also ‘nonconformal propositions.’

The ability of bees to inhibit symbolic reference does not, however, establish a nonhuman ability to grasp pure symbols. Whitehead notes this limitation, for while he freely allows that animals are capable of morality, because morality emphasizes the "detailed occasion," he states that they are not religious, because religion requires a grasp of pure ideality. Animals exist more immediately than human beings: the mental pole of animal consciousness is more closely tied to the physical pole. Hence the failure of animal consciousness to grasp the universal nature of ideality or symbol, as in number, structure, goodness, or other abstract concepts such as beauty and God. Whitehead offers an example of a failure to grasp universal ideality in his observations of a mother squirrel, who was "vaguely disturbed" in the process of moving her young due to her inability to count (MT 106-7). This failure to grasp the universal nature of ideality also results in animals, however virtuous, not qualifying as full-fledged moral agents (AAMB 52) 4

Nonverbal Thought. The limitation on the grasp of ideality by animals by no means rules out their ability to think. According to Whitehead, thought is not originally verbal or even gestural,5 though the "excitation" which is a thought does require expression of some sort (MT 50). Propositions are nonlinguistic entities and are usually entertained not only without language but without consciousness. Propositions are quasi-physical, in that they are "lures for feeling" at the unconscious physical level, lures which always involve valuation.

In current animal research, nonverbal propositions are termed "natural concepts," understood observationally as a consistent response to a category of perceived objects or events. Natural concepts are based on perceptual abstraction and are abstract to varying degrees. Premack suggests that the degree of abstraction can be measured by "transfer," a similar response to conditions other than those in which the organism was trained (OAHC 424). Species differ in their capacity for abstraction and hence for transfer. For example, whereas human beings, primates and cetaceans prehend some differences between stimuli by means of the category of "different" or "same," other species, such as pigeons, treat different stimuli according to their magnitude of difference from the training range. In addition, species differ in the weight they assign to relational factors (such as "darker than") as opposed to absolute factors (the stimulus value). Thus pigeons can be trained to put like items together (match-to-sample), but because pigeons’ behavior is based mainly on absolute rather than relational factors, pigeons fail to transfer relations, e.g., relations of hue to relations of brightness. In contrast, human beings, primates, dolphins (and seals) grasp categories of abstract relations, or second order relations, and are therefore able to transfer relations. In Whiteheadian terms these abstract relations are understood as more or less pure conceptual feelings.

The success of pigeons with cases of absolute value may be relevant to Richard Herrnstein’s finding that pigeons possess natural concepts of person, wee, and bodies of water, in the sense of recognizing these objects in many different pictures even when the size or angle of the representation is changed or it is mixed with a bewildering variety of other objects (CVPC 550). Pigeons can remember for years that a particular picture is rewarded. It is evident from these experiments that pigeons prehend certain eternal objects such as "tree" not as pure potentials but as illustrated in a particular type of structured society. Quail demonstrate similar capacities in forming natural, polymorphous concepts of phonetic categories (JQPC 1196). Some of the physiological basis for such natural concepts may be indicated in the recent finding that cells in the temporal cortex of conscious sheep respond preferentially to faces (CTCCS 450), a finding consonant with Whitehead’s position of the continuity of conceptual experience across species.

The German ethologist Koehler has demonstrated that some animals possess some forms of "wordless thinking" with regard to quantity. The wordless counting involves two capacities, the first being "seeing numbers" or choosing the object with a certain number of points on it from among a group of objects with points differing in number, size, color and arrangement. The second capacity is "to act upon a number" by repeating an act a certain number of times. Koehler found that the upper limit of both capacities for pigeons was five points, for parakeets and jackdaws six, for ravens, Amazons, gray parrots, magpies and squirrels, seven. The animals were able to translate a heard number into a seen one: to select a seven-dotted dish from others upon hearing seven arhythmical whistles, drum beats, or flashes of light. Numbers were grasped as spatiotemporal gestalts, requiring some sort of internal representation (TWW 80-85).

The capacity of primates to grasp abstract relations has been extensively tested by Premack with non-language trained chimpanzees on two kinds of reasoning: "and" versus "or" and transitive or deductive inference. All of the chimpanzees tested by Premack passed the "and/or" tests (MA 131). Premack comments that in his experimental design the distinctions between "and" and "or" could be made on the basis of images.

In a transitive series, A-B-C, if there is a relation between A and B and between B and C, then that relation holds for A and C. Four year old children, if given help in remembering the pairs, have made judgments which indicate transitive inference (AML 695). These results indicate that transitive reasoning may be a fundamental type of human reasoning. But Premack’s experiments indicate that transitive inference is also a fundamental reasoning process in primates. His experiments allowed the transitive inference to be accomplished with images of the order of the stimuli in the series, though exactly how the animals reasoned is not understood. Evidence of other researchers shows an almost exact equivalence of experimental results in the use of transitive inference by squirrel monkeys and four year old children.

In commenting on the results of experiments with pigeons and primates, Premack notes that since sentences contain both relational and absolute classes, a species’ potential for sentences depends upon its having both, as chimps, but not pigeons, demonstrably do.6

Consciousness. Whitehead’ s position that nonhumans enjoy aesthetic experience, moral experience, and nonverbal thought is well substantiated by recent investigations. But are nonhumans conscious of doing so? For Whitehead, consciousness is the subjective form of an intellectual feeling -- that is, a feeling of the contrast between what is, a physical feeling, and what could be, a propositional feeling. In other words, to be conscious of something is to be explicitly aware that it could be other than it is, and so one is aware of what it is. Conscious feelings "already find at work ‘physical purposes’ more primitive than themselves" (PR 273/416).

Intellectual feelings include conscious perceptions and intuitive judgments. Both kinds of intellectual feelings involve the "affirmation-negation contrast." In conscious perception, the emphasis falls on what is the case. There is heightened emotional intensity because of the added contrast. Intuitive judgments emphasize what is not the case. The origin of an intuitive judgment involves two separate sets of concrete, one of which is finally eliminated. The emotional pattern of the feeling of the intuitive judgment reflects the original disconnection of the predicate from the logical subjects. It is the contrast between what is and what is not but might be. Intuitive judgments are the "triumph of consciousness"; explicit negation is the "peculiar characteristic of consciousness" (PR 274/418).

Because most animals do not use verbal language, it has been difficult to ascertain whether or not they employ intuitive judgments. Whitehead makes no assertions in this area, but his silence gives the impression that animals do not experience such judgments. However, as we shall see, recent work demonstrates that some animals deceive. Full-blown instances of deception involve not only intuitive judgments, but self-awareness and the attribution of intentionality to others. Hence we will defer a discussion of deception until after we have considered self-awareness.

Conscious Perception. Donald Griffin, a cognitive ethologist, adopts an approach similar to the emphasis on novelty found in Whitehead’s definition of consciousness and suggests that the best evidence of conscious thinking and feeling in animals is provided by examples of actions which are versatile and adaptable to changing circumstances, as well as actions which involve interactive steps in a sequence of appropriate behavior patterns (AT 35). Griffin also confirms Whitehead’s position that the level of organization of the immediate environment determines the complexity of experience of an actual occasion. He suggests that consciousness results from "patterns of activity involving thousands or millions of neurons" (AT 44).

Griffin’s overall thesis is that conscious thought is the most economical explanation of a wide range of animal behavior. Animals have to constantly adapt to a changing environment and thus "conscious mental imagery, explicit anticipation of likely outcomes and simple thoughts about them are likely to achieve better results than thoughtless reaction" (AT 41). In fact because of the smaller storage capacity of the central nervous systems of animals, proportionately more of animals’ actions may be conscious than those of human beings, though simpler in nature.

Griffin argues also that there is no conclusive reason why instinctive behavior cannot be conscious. We involuntarily sneeze and flinch, but we know what we are doing. If the same brain states could result from genetic instruction ("instinct") as from involuntary action, instinctive actions would likewise be conscious. In addition, overt responses may not always accompany conscious thought (AT 41). Griffin further challenges the assumption of a "human monopoly on conscious thought" by noting that current experiments indicate that animals produce "event related potentials" which resemble those produced by human beings. ERP’s are a type of weak electrical signal (EEG) measurable from the outer surface of the scalp. Griffin is particularly interested in the "P300" wave, which is positive and peaks at approximately 300 milliseconds after the stimulus onset. "This wave seems to reflect complex information processing within the brain, and possibly something like conscious thinking, although that is not clearly established" (AT 147). The P300 wave has been shown to occur when the subject is expecting a stimulus that does not occur, that is, Whitehead’ s intuitive judgment. Human experiments suggest that if the subject is not paying conscious attention to a discrimination process, the P300 is greatly reduced or undetectable (AT 151). The time interval of the P300 wave may roughly reflect the duration of the dominant conscious occasion.7

Language. Some of the results of research into language use by primates bear directly on Whitehead’s view of the gradual emergency of language and of its usefulness. Premack states that "the curious consequence of language training seems to be that it weakens the characteristic difference between person and animal. For it appears to convert an animal with a strong bias for responding to appearance into one that can respond on an abstract basis" (MA 125). Language training produces an "upgrading of the ape’s mind" (MA 150).

Several different approaches are currently being used to explore the linguistic abilities of primates, two of which will be briefly described.8 Premack’s work, because it involves a language board, has facilitated the understanding of the abilities of chimps to grasp abstractions and logical relations, whereas Patterson’s work uses Ameslan and has been especially fruitful in exploring creative language use.

Premack began working with Sarah in 1967. She began with a magneticized language board, with an invented language. The board acted as an external memory for Sarah, important since chimps have a poor short-term memory. The "words" were pieces of colored plastic of differing color and shape, and were associated with objects and people. Sarah was required to observe a particular order in writing two or more words. She was able to understand simple word order, as in "Mary give apple Sarah" (MA 19). Sarah sometimes named fruits she desired rather than the one presented, indicating her ability to employ displaced or imaginative symbols. Sarah mastered the concepts of "on," "same," "different," "name of," use of questions and "no" (MA 27, 30).

Premack found that Sarah perceived a piece of plastic as having attributes of the signified. "For Sarah, then a blue plastic triangle represents a red, round object with a stem." However, Sarah was not able to match relations (cases of sameness and cases of difference) before she learned her language. Also, while she was able to solve problems of comparative proportion which did not involve changes in appearance, animals without language training were unable to. Her success required that she remember what objects which were not present looked like (MA 33).

To demonstrate that Sarah’s achievements were not based on perception of look-alikes but on her grasp of abstract relations, Premack tested Sarah’s ability to reason analogically, involving relations of change in size, color, shape and marking, as well as actions such as cutting, opening and marking. Sarah indicated that she had an abstract idea of opening by judging the relation of can opener to can the same as that of key to lock (MA 109). In other words, she understood second-order relations, a relation between relations.

Sarah also passed the test of conservation of liquid and solid quantity, in which contents of a flask are poured into flasks of different shapes or a piece of clay is changed in shape (CLSQ 994). In these tests she made accurate same-different judgments based on inferential reasoning. Premack then taught children Sarah’s plastic words for "same" and "different" and found that children of five or six were able to pass the same test.9

Overall, Premack’s work provides evidence of the general correctness of Whitehead’s view of the relationship between human and animal mentality -- that there is both a vast similarity and crucial differences. For example, apes have extreme difficulty with photo-object matching and with seeing the relationship between a TV picture of a space and the real space, or between a dollhouse model of a room and the real room (MA 99-108). Premack speculates that chimps may be more reliant on boundaries of representations than are children, and that TV images, dollhouses and photos do not make the boundaries of their compound and rooms clear enough (MA 148). Also, Premack points out that the difference between chimp language and human language is the difference between the construction and the sentence. In a construction, there is a simple one-to-one correspondence between words and the real world.

But Premack’s findings concerning Sarah’s abilities to conserve quantity, to reason analogically and to attribute object qualities to abstract symbols, does establish that primates are capable of more abstraction than Whitehead believed to be the case. Additional evidence for such ability is provided by the Gorilla Language Research Project, a longitudinal study of the linguistic and behavioral development of lowland gorillas. The project has two subjects, Koko and Michael, who have learned to use American Sign Language (Ameslan), to understand spoken English, and to read printed words.10 Koko’s instruction, begun in 1973, is the longest ongoing language study of an ape, and the only one with continuous instruction by the same teacher.

As of 1986 Koko has used over 500 different signs appropriately in Ameslan and understood as many English words. She communicates in statements averaging 3 to 6 signs in length. Michael, who joined the project about ten years ago, has learned over 250 signs. Koko’s IQ as measured on the Stanford Binet Intelligence Test is 85, and on the Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test is 81.6. In general her weaknesses are time or "when" questions and numbers beyond five, though she is able to refer to past and future within a scope of several days (RP 6; EK 199-200).

Both gorillas have exhibited a number of creative uses of language. Koko and Michael sometimes link words to create compound expressions for new objects and actions. For example, "eye hat" for a mask, "finger bracelet" for a ring, "bottle match" for a cigarette lighter, and "lettuce hair" for parsley. These usages parallel the speech of 2 to 5 year old children (MG 941). The gorillas also communicate new meanings by making up their own entirely new signs. The intended meaning of some of the gestures has been obvious because of their iconic form, but the meaning of others has had to be worked out. For example, Koko invented a sign for a game which translated as "walk-up-my-back-with-your-fingers" (MG 942-3).

Koko and Michael modulate signs without training in a number of ways. They may signal changes in degree of emphasis, number, agent-action, agent-object, location, size possession or negative aspect. For example, the sign "bad" can be made to mean "very bad" by enlarging the signing space, increasing the speed and tension of the hand, and exaggerating facial expression (MG 938). Emphasis is communicated by signing with two hands, and negation by changing the location of the sign. Modulation is also used to convert a statement into a question, through eye contact and facial expression. Koko also swears appropriately, using modulated signs (IULC 548-9).

When asked, "What can you think of that’s hard?" Koko answered, "rock . . . work." (CK 5). Though this response might be based on simple word association, a formal test established that Koko performed better than many seven year old children when the children were tested with the same instructions concerning metaphoric associations. She was asked to assign various descriptive words to pairs of colors. The results revealed that she assigned "warm" to red and "cold" to blue, "hard" to brown, and "soft" to blue-gray, etc. (IULG 535).

Like metaphor, humor requires a capacity to depart from what is strictly correct, normal, or expected. Wit or humor has been expressed many times by Koko and Michael. Thus it may be their intelligence which has given gorillas the unfortunate reputation of stupidity or contrariness. For example, when asked to "smile" for the camera, Koko signed "sad frown" (MG 938). Koko’s laugh is a low chuckle, like a "suppressed, heaving human laugh" (EK 144). Her humor seems to be incongruity based, like that of small children. Chuckles were evoked, for instance, by a research assistant accidentally sitting down on a sandwich and by another playfully pretending to feed M & M’s to a toy alligator. In a striking example combining metaphor and humor, Koko made a joke about being a "sad elephant" because she was reduced to drinking water through a thick rubber straw as a solution to her constant nagging one morning for more drinks of juice (IULG 534).

The use of language for its own sake is another indication that Koko has internalized a symbolic system. Koko began to sign to herself when 16 months old, most frequently during solitary play, and continues to do so (IULG 537-41). Frequently while looking through books and magazines she will comment to herself about what she sees. In summary, Koko’s creative use of language in humor, formation of new words, modulation of signs, understanding of metaphor, and self-directed signing provide evidence of both conscious perception and intuitive judgments.

Yet despite the impressive work of Premack and Patterson, their studies of language production by primates do not yet provide unequivocal evidence of the extent of the capacity of primates to understand the grammatical features of sentences. Also, most of the studies of the linguistic abilities of apes emphasize language production (though the work with Koko does include a study of her ability to comprehend spoken English). The study of language comprehension has some advantages over that of production, in that it can be tested under rigid controls, lends itself to statistical evaluation, and does not depend upon manual or vocal proficiency (CSBD 132-3). For these reasons, Louis Herman’s work with bottlenosed dolphins has focussed exclusively on language comprehension, particularly comprehension of the imperative sentence.

Herman’s study was rigorously designed to eliminate the possibility of cuing as well as of over-interpretation of the results. Beginning in 1979, he worked with two dolphins, teaching one an artificial acoustic language and the other an artificial gestural language. Within each language a sentence was defined as a sequence of words that expressed a unique semantic proposition, ranging in length from two to five words. The meanings of some of the sentences depended upon word order as well as the particular words used. Both lexically and syntactically novel sentences were used.

The training procedures were designed to teach the dolphins that concepts were general, applicable to a wide range of situations as well as to completely novel situations. While there was initial difficulty in assigning signs to objects (but not to actions), both dolphins readily came to understand that signs stand for referents. Herman notes that a major qualitative shift occurred during the course of the project in the way both dolphins appeared to process the names of objects. Initially they tended to encode the identity of the object in terms of its location, which of course constantly changed due to water movement, analogously to a chimp sitting in a room in which objects floated randomly about in the air (CSBD 204). Over time the dolphins developed the ability to encode the search for objects in terms of object attributes rather than location. The study included temporal displacement of up to 30 seconds between the presentation of the sentence and the appearance of the objects. The number of incorrect responses increased only slightly with the 30 second displacement. In addition, both dolphins were able to report the absence of designated objects after a search by pressing a paddle designated "No."

In discussing his results, Herman states that they demonstrate the ability of dolphins to respond correctly to semantically reversible sentences, offering "the first substantial evidence of syntactic processing of a string of lexical items by animals" (CSBD 199)12 Evidence for such syntactic processing is found in the dolphins’ correct responses to sentences having modifiers to direct and/or indirect objects: reversal errors were extremely rare. (A reversal error would be taking a specified indirect object to the specified direct object.) In addition, the dolphin Akeakamai understood that the word "erase" cancelled all operations on prior words, and the dolphin Phoenix responded to two conjoint sentences in a manner indicating her understanding of the semantic content of the entire conjoint sentence. Both dolphins responded correctly to novel, syntactical forms on the first presentation. At times the dolphins rearranged the circumstances to make the requested response possible or unambiguous, and on several occasions they performed actions which Herman thought not possible, such as "water toss" (CSBD 200). In other studies, dolphins have succeeded in getting their trainers conditioned to reinforcing stimuli which the dolphins used to achieve their own goals, and in getting the trainers to clarify the experimental situation (BLPW 418).

In summary, Herman’s work demonstrates that dolphins understand the significance of word order in imperative sentences. In addition, preliminary tests on the question form indicate that it is understood by Akeakamai as referring to the presence or absence of named objects. In Whiteheadian terms, we may say that dolphins entertain intuitive judgments. 13

Self-Consciousness. I propose that we understand self-consciousness as the subjective form characterized by a vivid feeling of "mineness" as it unifies high-grade multiple contrasts. This vivid feeling of mineness emerges in the self-conscious occasion because of the high degree of integrating activity of its subject-superject. A self-conscious occasion unifies the contrasts found in the conscious occasion -- that is, of what is and what might be -- by means of a subjective form characterized by the feeling of mineness, so that the occasion is aware that it is prehending these contrasts. 14 The feeling of mineness is not a sense of ownership or possession of particular mental states, but the awareness of being the center of experiencing. The experience has the flavor characterizing the particular defining characteristic(s) of myself as a living person. So understood, self-consciousness takes four forms.

The first form of self-consciousness is described by Duvall and Wicklund in their book A Theory of Objective Self-Awareness. They use the term "subjective self-consciousness" to describe my awareness when I am acting as an agent. However, because of the notorious vagueness of the term "subjective," I prefer the term "agent self-consciousness." Agent self-consciousness is the feeling of being the source of forces directed outward, of being the source of perception and action; it also involves peripheral feedback from the body. In Whiteheadian terms agent self-consciousness could be accounted for by the self-enjoyment of the concrescence as an at least partly self-determined process. In occasions which experience agent self-consciousness this self-enjoyment supplies the vivid quality of mineness to this self-determination. My experience includes the multiple contrast involved in my prehension of my actual world and the awareness of my freedom as an efficacious dominant occasion to control the activities of lower occasions, particularly those making up my motor responses and their effect on the world, but also including psychological responses.

The second type of self-consciousness is termed by Duvall and Wicklund "objective self-consciousness" and is the state in which the causal agent self is taken as the object of consciousness. I believe "public self-consciousness" to be a more precise and widely recognized term. Public self-consciousness arises in a situation in which by being looked at, about to give a speech, in front of a TV camera, etc., I take the objective, public standpoint concerning myself. Public self-consciousness can be accounted for by the presiding concrescence vividly inheriting the past presiding concretum as part of a multiple contrast involving the prehensions of both the observable and imagined feelings of the dominant concreta constituting a portion of the psyche of other people. Such a prehension includes the awareness that others are prehending my actions according to their own subjective forms, which may involve feelings and ideals differing from or enhancing the multiple contrasts I am entertaining. I am then self-consciously aware of myself as an object in the world, vulnerable to the interpretations of others.

In addition to agent and public self-consciousness and the various degrees and mixtures of the two, we also experience "introspective" or "private" self-consciousness, though it is less common than the public or agent forms, since it involves a purely "inward" focus of attention. I attend to my perceiving, feeling, imaging, thinking and deciding, rather than to myself as acting in the world or as a social object. Introspective self-consciousness involves causal objectification by the dominant occasion of some of the unimaginably large number of concreta making up the human mind/brain, including what can be called the subordinate nonconscious living persons responsible for our habitual behavior, that is, sub-personalities (RHNB 148f). The subjective form of introspective self-consciousness is the vivid quality of mineness involved in the multiple contrast of the various aspects of the inherited dominant concreta as well as subordinate concreta.

There is also a fourth form of self-consciousness, here termed "pure," which has been given little attention in Western philosophic works. 15 In pure self-consciousness I am vividly aware that I am other than the specific contents of my experience. This awareness cannot be objectified or known in the usual sense, and various religious traditions present varying descriptions of it. Also, we have no evidence of pure self-consciousness in nonhuman beings, though both the neurological and behavior complexity of cetaceans and perhaps elephants require us to leave this question open. For these reasons, I will not attempt a Whiteheadian account of this state, if indeed such would be possible. 16

We are now ready to consider to what degree these forms of self-consciousness are found in nonhuman experience. First, it is reasonable to attribute agent self-consciousness to mammals and birds, on much the same basis as we postulate it in young prelinguistic children (AT 205). All are organisms acting on the environment, with the concomitant bodily feelings (TOSA 2-3).

As for public self-consciousness, the pioneering work in primates was begun in 1970 by Gordon Gallup, Jr. Gallup uses mirrors in order to give "self-awareness," as the "capacity to become the object of one’s own attention," an observable meaning (SAP 418).17 Gallup initially observed that, after mirror exposure for two or three days, chimps spontaneously eliminated social responses to the mirror (acting as if they were seeing other chimps) and began to use the mirror to respond to themselves. For example, they would groom parts of their body they had not seen before and make faces at the reflection. Gallup then anesthetized chimpanzees who were familiar with the mirror and painted portions of their faces with a nonirritating dye. When the mirror was introduced, the chimps attempted to touch the marked areas with the aid of the reflected image. Chimpanzees who had never seen themselves in mirrors, however, as well as chimps reared in isolation, exhibited no patterns of self-recognition. The fact that chimps reared in isolation seemed incapable of self-recognition indicates that it is social experience rather than language which is one basis of public self-consciousness (SRCM 118). Gallup’s findings have been replicated by others and extended to include orangutans. Monkeys have failed to exhibit self-recognition even after extended exposure to mirrors, though monkeys are able to respond appropriately to mirrored cues as they pertain to objects other than themselves (SRMRM 239-40). 18 Gallup observes that children show signs of self-recognition in mirrors at 18-24 months, whereas severely retarded or schizophrenic human beings sometimes seem totally incapable of learning to recognize themselves in mirrors (SAP 418.)19

Gallup as well as other investigators have been puzzled by the apparent inability of gorillas to exhibit self-awareness (SRCOG 175). However, Patterson finds abundant evidence for self-awareness in her work with gorillas, including recognition of a mirror image, use of self-referential terms, linguistic descriptions of feelings (both the gorillas’ own and those of others), and behavior indicating embarrassment. For example, both Koko and Michael evidence public self-consciousness when they use self-referents in their conversations, as when asked, "Who is a smart gorilla?" Koko appropriately answered, "Me" (MG 940; SRG 2-3). Koko has on occasion corrected her human companions when they have labeled her with unfamiliar terms. When someone commented, "She’s a goofball," Koko replied, "No gorilla." Patterson reports that Koko and Michael have both used a mirror to make self-directed grooming responses (MG 934). In fact it may be gorilla sensitivity (public self-consciousness) which has interfered with the attempts of other investigators to demonstrate gorilla self-awareness. For example, Koko seems embarrassed when her companions note that she is signing to herself, especially when the signing involves her dolls and animal toys. In one remarkable example she seemed to structure an imaginative social situation between two gorilla dolls, and signed "Good gorilla, good, good" when she was finished. She then noticed that a teacher was watching and left the dolls (IULG 540-1).

Koko exhibits introspective self-consciousness when she reports "Me feel fine" or that she feels sad (as when recovering from flu) or jealous (as when watching Michael and his teacher walk outside). When asked what is boring, she responded, "Think eye ear eye nose boring." Patterson comments, "Apparently Koko finds drill on overlearned things such as body parts boring" (IJLG 556). The gorillas have sometimes talked about their feelings concerning situations removed in time and space from the current one. Several months after her famous kitten "All-Ball" died, Koko was asked how she felt and replied, "Red red red bad sorry Koko-love good." (In other contexts Koko has seemed to associate "red" with anger.)

Koko exhibited introspective self-consciousness as well as Premack’s second-level intentionality when she saw Michael crying because he was not allowed out of his room, and on being asked how Michael felt, she responded, "Feel sorry out." In another example, after telling Koko she (the teacher) felt sad, the teacher asked Koko what she (the teacher) could do to feel better. Koko replied, "Close drapes" (Koko finds the closing of drapes over her windows to be comforting) and "Tug-of-war." Koko then came quietly up to the teacher and signed "sad"? (raising her eyebrows and leaning forward). The teacher responded, "I feel better now" and Koko smiled (CK 8).

Deception. The act of deception requires self-awareness, the ability to inhibit symbolic reference, and intentionality. Deception in both children and primates seems to develop gradually in a stage by stage sequence concomitant with sensorimotor intelligence and is inextricably related to intelligence (EODH 217). Children and apes both become capable of deception at around 18 months to two years of age.

In connection with her research with the orangutan Chantek, H. Lyn Miles offers a five-level schemata of deception. In her level four, "intentional deception," the animal misuses an action or sign in order to obtain a goal. The animal’s action, as well as his or her signs, indicate one intention, but when this intention is fulfilled, another is apparent. Cues which might reveal the deception are suppressed. Thus Chantek asked to see a monkey but instantly grabbed tools once inside the room which he knew to contain both monkey and tools (HCR 263).

Miles’ highest level of deception is "deception with false cues," in which the animal actively tries to thwart the other’s recognition of a falsehood by providing false messages which support the falsehood, whereas at level 4 the animal provides only true messages which support the falsehood (HCTL 264). Level 5 thus represents a clear instance of intuitive judgment as defined in Whitehead’s system. An example of level 5 is an incident in which Chantek hid an eraser but indicated with both behavior and signs that he had eaten the eraser (he opened his mouth for his trainer to see inside and signed "Food, eat").

There is an additional useful distinction to be made concerning deception: that between naive deception and what might be termed "deception-awareness."20 Intentional deception can occur naively, that is, the animal suppresses cues or provides false cues in order to manipulate the other’s behavior, but he or she may still take the other’s behavior at face value -- may still trust the other. A more complex level of deception (level 6?) occurs when the animal becomes aware that others may also deceive. This "deception-awareness" corresponds to Premack’s more general term "second level intentionality." When an animal experiences deception-awareness it mistrusts the other; it has lost its innocence and is initiated into the possibility that others may be untrustworthy. Yet only when the other is fully differentiated as a possible deceiver does relationship in its fullest sense emerge. Thus we can distinguish a level 7 of deception, in which I refrain from deceiving you because I empathize with how you will feel if I do deceive you, having experienced such deception myself. Level 7, perhaps describable as "altruism," represents the emergence of morally principled action.

How far along this hierarchy of deception are chimps21 able to travel? In his study of intentional deception in chimps, de Waal provides many examples of suppression of cues, exploitation of the ambiguity of cues, and use of false cues. Indeed, chimps are so skilled at deception that human observers often miss the whole action unless he or she witnessed the moment at which it began. Chimps are also skilled in combining feigned interest (false cues) with camouflaged responses (suppression of cues). They may turn their attention to something unimportant in order to hide embarrassment or disappointment. Thus, after a negative experience they may "carefully inspect details of their own body, similar to the way a tennis player concentrates on the string of his or her racket after a bad return" (FDD 23).

Signals can be corrected in order to suppress cues. For example, teeth-baring is a sign of fear and nervousness in chimps. One male, sitting with his back to his challenger, showed a grin upon hearing hooting sounds. He quickly used his fingers to push his lips back over his teeth again. The manipulation occurred three times before the grin ceased to appear. After that, the male turned around to bluff back at his rival. Female chimps often falsify cues using the "lure," in which false conciliatory overtures are given, to be followed by a swift attack. Feigning a mood is another form of chimp deception involving false cues. One old male observed by de Waal feigned being in a very good mood, tickling and rolling around with juveniles, despite all provocations (DNCC 232).

Koko has deceived by both using ambiguous cues and by providing false cues. For example, when caught in the act of trying to break a window screen with a chopstick she had stolen from the silverware drawer, she placed the chopstick in her mouth as though she was smoking it and signed "Smoke mouth." Koko has deceived Michael with false signing (TUP 10). She has been also able to answer some why questions. When asked, twenty minutes after the event, why she had bitten a companion who violated her rules of ball play, she responded "Him ball bad." She was also asked three days after biting Patterson, "Why bite?" "Because mad." Patterson: "Why mad?" Koko: "Don’t know" (IULO 544-5).

Up to this point we have noted evidence of intentional deception. Can we go further and find experimental evidence of deception-awareness or second-level intentionality in primates, or even of level 7, altruism?22 Here Premack’s work is suggestive, though as Chevalier-Skolnikoff points out, his use of juvenile chimps may explain the limited nature of his results (ODHN 214)23 Only one of his four animals both avoided a hostile trainer’s directions and deliberately misdirected the hostile trainer, while continuing to correctly inform and to accept information from the helpful trainer (IC 357). Not surprisingly, Premack found that the suppression of cues always preceded the production of false cues. The chimps did surprise Premack by beginning to point during the experiment, since pointing is not natural to the chimpanzee. However, none of Premack’s chimps have transferred the point to nonexperimental situations (IC 358).

In a series of carefully designed and ingenious experiments involving videotapes of problem situations with possible solutions, Premack has directly explored the chimp’s capacity for second-level intentionality (MA 57-67). In these experiments Sarah consistently identified the correct solution to a videotaped sequence of events illustrating a problem situation, whereas about half a group of normal 31/2 year old children responded not to the problem but to sensory aspects of the event. In another experiment Sarah consistently chose good solutions to problems for the actor she liked and bad solutions to the problems for the actor she disliked. Exactly what capacities are required for such performance is not understood, but they would seem to include second-level intentionality of a simple sort.

Sarah seemed to reach her limits at "third-level intentionality," that is, the level of attributing attributions to others. She was unable to attribute to X the capacity of attributing intentions to Y. Third-level intentionality is necessary for a full-fledged moral life, though nonhuman beings do exhibit aspects of morality, such as virtuous actions.

We have seen that research in nonhuman experience corroborates Whitehead’s epistemological scheme in which perception takes the two forms of causal efficacy and presentational immediacy, propositions and concepts are primarily nonlinguistic, feeling is the dominant mode of world- and self-disclosure, and animals experience both morally and aesthetically. It is also apparent that the recent evidence for self-consciousness in primates and cetaceans, based on their capacity for language use and deception, requires us to acknowledge that nonhuman capacities are somewhat closer to human capacities than Whitehead asserted. Overall, Whitehead’s theory does indeed enable us to escape anthropocentric dogmas. He helps us to realize that, properly understood, animals are not mere instruments for human use, but are companions in our evolutionary adventure.

References

AA -- Michael Allaby. Animal Artisans. New York: Alfred Knopf, 1982.

AAMB -- S. F. Sapontzis. "Are Animals Moral Beings?" American Philosophical Quarterly 17:1 (1980): 45-52.

AML -- Brendan O. McGonigle and Margaret Chalmers. "Are Monkeys Logical?" Nature 267 (23 June 1977): 694-96.

ANAN -- W. H. Thorpe. Animal Nature and Human Nature. Garden City, NJ: Doubleday, 1974.

AT -- Donald Griffin. Animal Thinking. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1984.

BB -- A. J. Marshall. Bower-Birds. Their Displays and Breeding Cycles. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1954.

BLPW -- Karen W. Pryor. "Behavior and Learning in Porpoises and Whales." Naturwissenschaften 60 (1973): 412-20.

BS -- Charles Hartshorne. Born to Sing: An Interpretation and World Survey of Bird Song. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 1973.

BV -- Bird Vocalizations. Ed. R. A. Hinde. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1969.

CK -- Barbara Hiller. "Conversations with Koko." Gorilla Journal 6:2 (June 1983): 5.

CK -- Barbara Hiller and Mitzi Phillips. "Conversations with Koko." Gorilla Journal 10:1 (December 1986): 7-8.

CLSQ -- David Premack, Guy Woodruff and Keith Kennel. "Conservation of Liquid and Solid Quantity by the Chimpanzee." Science 201:1 (Dec. 1978): 991-94.

CMC -- Emil W. Menzel. "Cognitive Mapping in Chimpanzees." Cognitive Processes in Animal Behavior. Ed. S. H. Hulse, H. Fowler and W. F. Honig. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum, 1978.

CP -- Karen W. Pryor. Richard Haag, Joseph O’Reilly. "The Creative Porpoise: Training for Novel Behavior." Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior 12 (1969): 653-661.

CPS -- David Premack and Guy Woodruff. "Chimpanzee Problem-Solving: A Test for Comprehension." Science 202:3 (Nov. 1978): 532-35.

CSBD -- Louis M. Herman, Douglas G. Richards, and James P. Wolz. "Comprehension of Sentences by Bottlenosed Dolphins." Cognition 16 (1984): 129-219.

CSPC -- Steven Schindler. "Consciousness in Satisfaction as the Pre-reflective Cogito." PS 5:3 (1975): 187-90.

CSPS -- E. W. Menzel, Jr., E. Sue Savage-Rumbaugh, and Janet Lawson. "Chimpanzee (Pan troglodytes) Spatial Problem Solving with the Use of Mirror and Televised Equivalents of Mirrors." Journal of Comparative Psychology 99(1985): 211-17.

CTC -- K. M. Hendrick and B. A. Baldwin. "Cells in Temporal Cortex of Conscious Sheep can Respond Preferentially to the Sight of Faces." Science 236 (1987): 448-50.

CVCP -- Richard Herrnstein. "Complex Visual Concept in the Pigeon." Science 146 (1964): 549-51.

D -- Deception: Perspectives on Human and Nonhuman Deceit. Ed. Robert W. Mitchell and Nicholas S. Thompson. Albany, NY: SUNY, 1986.

DARL -- James Rachels. "Do Animals Have a Right to Liberty?" Animal Rights and Human Obligations. Ed. Tom Regan and Peter Singer. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall, 1976.

DHK -- J. L. Gould. "Do Honeybees Know What They are Doing?" Natural History 88 (1979): 66-75.

DNCC -- Frans de Waal. "Deception in the Natural Communication of Chimpanzees." In D, 221-244.

EK -- Francine Patterson and Eugene Linden. The Education of Koko. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1981.

EODH -- Suzanne Chevalier-Skolnikoff. "An Exploration of the Ontogeny of Deception in Human Beings and Nonhuman Primates." In D, 205-20.

FDD -- Robert W. Mitchell. "A Framework for Discussing Deception." In D, 3-40.

GDMP -- E. W. Menzel, Jr. "General Discussion of the Methodological Problems Involved in the Study of Social Interaction." Social Interaction Analysis. Ed. M. Lamb, S. Suomi and G. Stephenson. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1979.

HCTL -- H. Lyn Miles. "How Can I Tell a Lie? Apes, Language, and the Problem of Deception." In D, 245-266.

IC – Guy Woodruff and David Premack. "Intentional Communication in the Chimpanzee: The Development of Deception." Cognition 7(1979): 333-362.

IDBR -- Nubio Negrao and Werner R. Schmidek. "Individual Differences in the Behavior of Rats (Rattus norvegicus)." Journal of Comparative Psychology 101:2 (1987): 107-111.

IULG -- Francine Patterson. "Innovative Uses of Language by a Gorilla: A Case Study." Children’s Language. Vol. 2. Ed. Keith Nelson. New York: Gardner, 1980.

JLA -- Maurice Burton. Just Like an Animal. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1978.

JQPC -- Keith R. Kluender, Randy L. Diehl, and Peter R. Killeen. "Japanese Quail Can Learn Phonetic Categories." Science 237(4 Sept. 1987): 1195-1197.

LIAM -- David Premack. "Language and Intelligence in Ape and Man." American Scientist 62 (1976): 674-683.

MA -- David Premack and Ann James Premack. The Mind of an Ape. New York and London: Norton, 1983.

ME -- Elizabeth M. Krause. The Metaphysics of Experience. New York: Fordham University Press, 1979.

MG -- Francine Patterson. "The Mind of the Gorilla: Conversation and Conservation." Primates: The Road to Self-Sustaining Populations. Ed. K. Benirschke. New York: Springer-Verlag, 1986.

MMD -- Konrad Lorenz. Man Meets Dog. Trans. Marjorie Wilson. London: Penguin Books, 1964.

NT -- Jacques Gravens. Non-Human Thought: The Mysteries of the Animal Psyche. New York: Stein and Day, 1967.

OAHC -- David Premack. "On the Abstractness of Human Concepts: Why It Would be Difficult to Talk to a Pigeon." Cognitive Processes in Animal Behavior. Ed. S. H. Hulse, H. Fowler and W. F. Honig. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum, 1978.

RC -- Gordon Gallup, Jr. "Reason in the Chimp: I. Analogical Reasoning." Journal of Experimental Psychology 7:1 (Jan. 1981): 1-13; "Reason in the Chimp: II. Transitive Inference." Ibid., 7.2 150-164.

RNHB -- Susan B. Armstrong. "The Rights of Nonhuman Beings. A Whiteheadian Study." Diss. Bryn Mawr College, 1976.

RP -- Anne Longman. "Reading Project." Gorilla Journal 6:2 (June 1983): 6.

SAP -- Gordon Gallup, Jr. "Self-Awareness in Primates." American Scientist 67 (1979): 417-21.

SCTP -- David Lubinski and Kenneth MacCorquodale. "‘Symbolic Communication’ Between Two Pigeons (Columba livia) Without Unconditional Reinforcement." Journal of Comparative Psychology 98:4 (1984): 322-80.

SRCM -- Gordon G. Gallup, Jr. "Self-Recognition in Chimpanzees and Man: A Developmental and Comparative Perspective." The Child and Its Family. Ed. Michael Lewis and Leonard A. Rosenblum. New York: Plenum, 1979.

SRCOG -- Susan D. Suarez and Gordon G. Gallup, Jr. "Self-Recognition in Chimps and Orangutans, but Not Gorillas." Journal of Human Evolution 10(1981): 175-188.

SRG -- Francine Patterson. "Self-Recognition by Gorilla gorilla gorilla." Gorilla Journal 7:2 (1984): 2-3.

SRMRM -- Susan Suarez and Gordon Gallup, Jr. "Social Responding to Mirrors in Rhesus Macques (Macaca mulatta): Effects of Changing Mirror Locations." American Journal of Primatology 11(1986): 239-244.

TOSA -- Shelley Duval and Robert A. Wicklund. A Theory of Objective Self-Awareness. New York: Academic Press, 1972.

TUP -- Janet Cebula. "Tales of an Understaffed Project." Gorilla Journal 9.1 (Dec. 85): 9-10.

TWW -- Otto Koehler. "Thinking Without Words." Proceedings of the 14th International Zoological Congress (Copenhagen, 1953): 75-88.

Notes

1Whitehead rules out an actual entity being conscious of its own satisfaction because such consciousness would require objectification (PR 85/130). However, as Schindler has suggested, self-consciousness could be understood as immanent in the present moment of experience as a nonthetic consciousness which would not amount to knowledge in the sense of objectification. However, this nonthetic consciousness would not qualify as consciousness under Whitehead’s definition. See CSPC 187-90.

2 Whitehead allows for indefinitely higher grades of contrasts (PR 22/33).

3‘Concretum’ is a term coined by George L. Kline to refer to the "post-concrescent product of concrescent processes," a "perished" concrescence. See G. L. Kline, "Form, Concrescence, and Concretum," Explorations in Whitehead’s Philosophy, ed. Lewis S. Ford and George L. Kline (New York: Fordham University Press, 1983), 104-46.

4 For a fuller discussion, see RNHB, chaps. 3-5.

5 In his field study of chimpanzees, Menzel states that to equate communicative ability to gestural or vocal responses is anthropocentric. See CMC.

6 Dolphins have been shown to form the concept of novelty in experiments in which they are rewarded for maneuvers never before executed. Interestingly, a pigeon was also trained to perform a new action each day. Examples included lying on its back, standing with both feet on one wing, and flying up into the air a few inches and hovering there. Karen Pryor, Lads before the Wind (New York: Harper and Row, 1975), 248f.

7Experimental evidence in human beings shows that rare and more complex stimuli elicit larger P300 potentials with a larger latency.

8A third prominent effort is that of Duane and Sue Rumbaugh, utilizing a modified computer. See Language Learning by a Chimpanzee: The Lana Project, ed. Duane M. Rumbaugh (New York: Academic Press, 1977). For an excellent overview and critique of all of the primate language investigations, see Carolyn S. Ristau and Donald Robbins, ‘Language in the Great Apes: A Critical Review," Advances in the Study of Behavior, ed. Jay S. Rosenblatt, Robert A. Hinde, Colin Beer and Marie-Claire Busnel, vol. 12 (New York: Academic Press, 1982), 141-255.

9 Other investigators have found similar results with a chimp using the terms "same" or "different." See Steven J. Muncer, "Conversations with a Chimpanzee," Developmental Psychology 16:1(1983): 1-11.

10 Recently the Gorilla Foundation has adopted the term "simultaneous communication" (SimCom) to refer to this system, in which a communicator uses gestural signs and verbal speech at the same time. See Gorilla Journal 10:2 (June 1987): 2.

11 Koko’s spontaneous use of questions challenges Premack’s claim that the ape is incapable of recognizing deficiencies in its own knowledge (MA 26).

12 Herman’s more recent work indicates that language experience affects what features are attended to by both dolphins and human beings in sign recognition. See Melissa R. Shyan and Louis M. Herman, "Determinants of Recognition of Gestural Signs in an Artificial Language by Atlantic Bottle-Nosed Dolphins (Tursiops truncatus) and Humans (Homo sapiens)," Journal of Comparative Psychology 101:2 (1987): 112-25.

13 Similar tests with a sea lion established a comprehensive repertoire of sentence lengths up to 7 signs. Ronded J. Schusterman and Kathy Kzieger, "Artificial Language Comprehension and Size Transposition by a California Sea Lion (Zalophus californianas);" Journal of Comparative Psychology 100:4 (1986): 348-355.

14 No occasion considered by itself can be self-conscious, or even alive, since many subordinate societies, both organic and inorganic, are required as preconditions for the attainment of the complexity of self-consciousness.

15 Parantje maintains that the existence of a "no thought" zone of consciousness can be verified by anyone willing to follow yogic or Vedantic methods, and that Husserl’s reductive phenomenology is similar to yogic methods. See A. C. Paranjpe. Theoretical Psychology. The Meeting of East and West (New York and London: Plenum Press, 1984), 203ff.

16 Ernest L. Simmons, Jr., has pioneered a helpful account in "Mystical Consciousness In a Process Perspective" PS 14:1 (1984): 1-10. 1 believe, however, that his emphasis on pure self-consciousness as simply the experience of causal efficacy does not fully allow for the experience of freedom from determination by the contents of consciousness as well as for other higher-order experience.

17We should note, however, with regard to all use of self-recognition in mirrors as an indicator of self-consciousness that self-consciousness probably goes through many developmental transformations, some of which may not lend themselves to mirror testing. Also, there may be modality-specific senses of self(e.g.. hearing as opposed to sight). See James R. Anderson, "The Development of Self-Recognition: A Review," Developmental Psychology 17:1 (1984): 35-49.

18 Other studies indicate that chimps but not rhesus monkeys are able to recognize themselves on television (CSPS 211).

19On the similarity of development of mirror behavior in humans and nonhumans, see S. Robert, "Ontogency of Mirror Behavior in Two Species of Great Apes." American Journal of Primatology 10 (1986): 109-117.

20 This term was suggested to me by Whitney W. Buck.

21 Deceptive interactions have also been observed in a group of captive Asian elephants. See Maxinne D. Morris, "Large Scale Deceit: Deception by Captive Elephants?" (D 183-191).

22 Experiments with children indicate that the recursive awareness of intention (second-level intentionality) develops between the ages of 3 and 5. See Thomas R. Shultz and Karen Gloghesy, "Development of Recursive Awareness of Intention," Developmental Psychology 17:4 (1981): 465-471.

23 She also notes that in her studies gorillas give clearer evidence of deception than do chimps or orangutans.

In the process of this application it will be necessary to attempt an account of self-consciousness consistent with Whitehead’s system. While Whitehead’s writings are rich in the systematic description of consciousness per se, he does not use the term "self-consciousness" systematically and mentions it only once in Process and Reality (107/164).1 In the attempt to obtain clarity in this regard I propose we consider self-consciousness to be a subjective form characterized by higher and more complex contrasts2 than exhibited by consciousness per se. In addition, I propose that we distinguish four types of self-consciousness: agent, public, introspective and pure. I will argue that three of these types of self-consciousness are clearly exhibited by language-using primates and quite probably by many other animals. Pure self-consciousness, however, seems to be an achievement rare even for human beings.

Understanding Nonhuman Beings. Whitehead’s distinction between two modes of perception is a highly useful one in evaluating past and present research designs concerned with animal experience. In the twentieth century, such research has relied almost exclusively on perception in the mode of presentational immediacy, that is, on quantified sense data devoid of a sense of past inheritance and thus devoid of meaning, emotion or purpose. It is apparent that perception in this mode does not disclose mental functioning. Whitehead’s system allows us to come to terms with this situation, since perception in the mode of causal efficacy involves the prehension of the outcome of both the mental and physical poles of the concretum3 as well as the subjective form, the "feel" of individual experience (insofar as it can be felt by a subsequent concrescence). Thus vague though powerful emotions and intuitions need no longer be ruled out as merely subjective and hence irrelevant, unscientific responses to the data.

It is of course true that careful observation requires the use of controls, the elimination of the possibility of social cuing, guarding against uncritical projection of the observer’s prejudices and presuppositions, etc. (MA 83-98). But increasingly researchers in this field are coming to agree that careful observation also requires an acknowledgement of the emotion, meaning and purpose in nonhuman experience. Attention to our intuitive and feelingful sense of our connections with the surrounding world, including other animals, is necessary in order to make correct interpretations.

Konrad Lorenz states:

Nobody can assess the mental qualities of a dog without having once possessed the love of one, and the same thing applies to many other intelligent socially living animals, such as ravens, jackdaws, large parrots, wild geese and monkeys. (MMD 162)

More recently, Menzel has observed that "we need very much to develop and refine methods which explicitly recognize and exploit, rather than attempt to eliminate, the observer’s prescientific, intuitive and global forms of judgment" (GDMP 303).

De Waal and colleagues have been testing human intuition concerning the behavior of chimps at the Arnheim Zoo since 1976. He states, "that the same testing principle was independently proposed by Menzel is illustrative of the new Zeitgeist" (DNCC 224). He adds that the scientists unwilling to attribute intentionality to animals are generally those with little direct experience with the behavior of nonhuman primates (DNCC 221). De Waal has found that short-term predictions of aggressive behavior based on the subjective evaluation of the personality, mood and frustrations of the chimps were much more reliable than estimations based on objective categorizations and explicit rules (that is, on quantitative and sensory-based criteria). De Waal points out that the basis of such intuitions is difficult to convey to others, due to the subtleties of primate interactions. The "look in the eye" of a primate can convey whether or not the action was intentional (DNCC 222)

Nohuman Aesthetic and Moral Experience. Whitehead asserts that animals experience emotions, hopes and purposes, largely derived from bodily functions, and yet "tinged to a degree with conceptual functioning" (MT 37). "The animals enjoy structure: they can build nests and dams: they can follow the trail of scent through the forest" (MT 104). Observations unknown to Whitehead offer striking examples of the ability of some animals to enjoy sensuous contrasts and structures for their own sakes. Birds offer many of the best examples. Bowerbirds, a family of passerine birds which live in the rain forests of Australia and New Guinea, build bowers laid out so that the sun will not blind the bird while he dances in the presence of the female. The bowers have a display ground decorated with colored objects, chosen with great care as to their color and form (BB 42, 47-51). Some birds paint the walls of their bowers with fruit pulp, wet powdered charcoal, or a paste of chewed-up grass mixed with saliva. The satin bowerbird uses a wad of bark with which to apply the paint; the bower painting varies greatly among individual birds, regardless of their color or maturity (BR 37-9).

Bird song has given aesthetic pleasure to human beings for untold years. Does it also give aesthetic pleasure to birds? It appears so. Joan Hall-Craig states of blackbird songs that "the constructional basis appears to be identical to that which we find in our own music." There is rhythmic impulse and recoil in the organization of motifs and matching of tonal and temporal patterns to form symmetrical wholes (BV 375-6). To human ears, the aesthetic value of a bird song suffers when the bird must become practical and repel an intruder or attract a mate (ANHN 105-31). Charles Hartshorne has devoted much trained attention to bird song and argues that song requires "something like an aesthetic sense in the animal," though it may be more a matter of aesthetic feeling rather than aesthetic thought (BS 2, 12).

Whitehead attributes morality to the higher animals, in addition to their enjoyment of form. By this he seems to mean that animals exhibit a sense of foresight and self-transcendence. Along the same lines, Sapontzis argues that animals’ intentional and sincere, kind and courageous actions are moral actions, for they accord with accepted moral norms, and we do not require demonstrations of moral principle in everyday human moral practice (AAMB 51-2).

By understanding morality in this way, we can find abundant examples of moral actions. For example, mutual aid has been observed in 130 different species of birds (NT 167). Burton, an experienced ethologist, states that animals are capable of compassion, pity, sympathy, affection and grief, as well as true altruism (JLA 91). Rachels has described an experiment with rhesus monkeys in which not only did monkeys refrain from eating for many days in order not to shock another monkey, but the willingness to undergo such hunger was correlated with (1) whether or not the monkeys had been cagemates and (2) whether or not the hungry monkey had itself been in the situation of the monkey undergoing the shocks. Thus the altruistic behavior was directly related to the vividness of the empathy felt by the hungry monkey (DARL 215-6). We should also note the many instances of intra and inter-species helping behavior exhibited by dolphins (MW 166-68). Whitehead recognizes such animal goodness in a memorable passage:

Without doubt the higher animals entertain notions, hopes and fears. And yet they lack civilization by reason of the deficient generality of their mental functioning. Their love, their devotion, their beauty of performance, rightly claim our love and our tenderness in return. Civilization is more than all these; and in moral worth it can be less than all these. (MT 5, emphasis added)

Symbolic Reference. Whitehead distinguishes human beings from animals on the basis of different capacities for the inhibition of symbolic reference. The inhibition of symbolic reference frees the conceptual element as exemplified in presentational immediacy from its exemplification in causal efficacy and thus frees the symbol to carry meanings other than those conveyed by the immediate past (ME 80; S 6, 83f).