- Home

- Process Worldview

- Community

- Art and Music

- Whitehead and Process Thinking

- Podcasts

- Spirituality

- Ecological Civilization

- Education

- Contact

- Social Justice

- Science

- Animals

- Sacred Poems

- Whitehead Videos

- Index of All Titles

- Practicing Process Thought

- Process Spirituality: A Spiritual Alphabet

- Recent Posts

I listened, motionless and still;

And, as I mounted up the hill,

The music in my heart I bore,

Long after it was heard no more.

-- William Wordsworth, The Solitary Reaper

And, as I mounted up the hill,

The music in my heart I bore,

Long after it was heard no more.

-- William Wordsworth, The Solitary Reaper

Traditional folk music has been defined in several ways: as music transmitted orally, or as music with unknown composers. It has been contrasted with commercial and classical styles.

One meaning often given is that of old songs, with no known composers; another is music that has been transmitted and evolved by a process of oral transmission or performed by custom over a long period of time.

--Wikipedia, Folk Music

One meaning often given is that of old songs, with no known composers; another is music that has been transmitted and evolved by a process of oral transmission or performed by custom over a long period of time.

--Wikipedia, Folk Music

What the song Scarborough Fair

means to People: Interviews

Where is Scarborough Fair?

A Process Interpretation

The High Holy Day Prayerbook refers to God as Zokher Ha-Nishkachot, the One who remembers what is forgotten.

- Rabbi Bradley Shavit Artson

In listening to songs once forgotten, we join the One who remembers in the deep remembering, albeit in our own finite way. We try to catch glimpses of lives forgotten, with sufferings and joys not unlike our own, carried in song.

If we are people of faith, we may intuitively trust that Soul of the universe -- the womb-like Life in whose experience the universe unfolds -- feels their feelings "with tender care that nothing be lost," as Whitehead puts it. Our listening is our small addition to the infinite empathy often named "God."

But of course there's something in it for us, too. Traditional folk music brings with it the comfort of the familiar and the lure of fresh possibilities. It provides a context for what most people seek throughout their lives: roots and wings.

The roots are clear enough. As Sandra Kerr puts it in the BBC interview: "Songs are about people’s lives. They represent their history, their language, their family, their place of origin." And yet, as we hear the voices of those who existed before us, we sense new possibilities for how we might live in the world and who we might become.

We realize that Scarborough Fair is not simply in the past but also in the future. It is an enchanted place that may never have existed as we imagine it, but that nevertheless exists as a possibility which lures us forward. Scarborough Fair brings with it the possibility that the world itself may be more enchanted -- more alive and beautiful, more mysterious and wondrous -- than the mechanistic worldviews of modernity ever quite allow.

Of course not all traditional folks songs are quite as pretty. They can reveal the pain of the past: the injustices, the barbarities, the violence, and, needless to say, lost loves. Many of them -- Scarborough Fair, for example -- reveal loss and promise at the same time. And yet, just as the Deep Remembering carries within it a remembrance of the atrocities as well as the hopes, so must a life well-lived carry them.

The One who remembers what has been forgotten begins with honesty and turns to hope.

*

So where is Scarborough Fair? It is an enchanted place in the mind, associated with the city of Scarborough, England, now calling from the future. Its call is about romantic love, and also about a re-enchanted world, somewhere between the salt water and the sea strand, filled with parsley, sage, rosemary, and thyme.

In this imaginary land we recognize anew the preciousness of human life and also the aliveness of all things: the numinosity of rocks, for example. A featured columnist for Open Horizons, Patricia Adams Farmer, knows the rocks well, and gives us a sense of what re-enchanted eyes might see.

"The energy of rocks is particularly mysterious and primordial. I love to pick up a small rock from the wet sand and feel its warmth in my hand, even on chilly, sweatshirt days when the clouds hang low and the the volcanic sand cools my feet. A rock holds the energy of the sun long after everything around it succumbs to darkness and chill. The warm energy of the rock feels as if it were a living thing. And, in a sense, it is. And its “life” radiates a personality of something strong and trustworthy—and forever present in the world, remaining long after we are gone. The rock is very sure of itself, of its past and its future. And it has reason to be. When we pick up a rock, we are not just holding a lump of minerals: we are holding a piece of eternity in our hands." (Patricia Adams Farmer, The Numinosity of Rocks)

Imagine, then, a world where we hold rocks with respect for their numinosity and one another even more carefully. Such a world does not emerge all at once or even once and for all; but even mere approximations of it are worth dreaming. Such are the dreams of which God is made, and through which God is found. They are well worth the pilgrimage.

-- Jay McDaniel

- Rabbi Bradley Shavit Artson

In listening to songs once forgotten, we join the One who remembers in the deep remembering, albeit in our own finite way. We try to catch glimpses of lives forgotten, with sufferings and joys not unlike our own, carried in song.

If we are people of faith, we may intuitively trust that Soul of the universe -- the womb-like Life in whose experience the universe unfolds -- feels their feelings "with tender care that nothing be lost," as Whitehead puts it. Our listening is our small addition to the infinite empathy often named "God."

But of course there's something in it for us, too. Traditional folk music brings with it the comfort of the familiar and the lure of fresh possibilities. It provides a context for what most people seek throughout their lives: roots and wings.

The roots are clear enough. As Sandra Kerr puts it in the BBC interview: "Songs are about people’s lives. They represent their history, their language, their family, their place of origin." And yet, as we hear the voices of those who existed before us, we sense new possibilities for how we might live in the world and who we might become.

We realize that Scarborough Fair is not simply in the past but also in the future. It is an enchanted place that may never have existed as we imagine it, but that nevertheless exists as a possibility which lures us forward. Scarborough Fair brings with it the possibility that the world itself may be more enchanted -- more alive and beautiful, more mysterious and wondrous -- than the mechanistic worldviews of modernity ever quite allow.

Of course not all traditional folks songs are quite as pretty. They can reveal the pain of the past: the injustices, the barbarities, the violence, and, needless to say, lost loves. Many of them -- Scarborough Fair, for example -- reveal loss and promise at the same time. And yet, just as the Deep Remembering carries within it a remembrance of the atrocities as well as the hopes, so must a life well-lived carry them.

The One who remembers what has been forgotten begins with honesty and turns to hope.

*

So where is Scarborough Fair? It is an enchanted place in the mind, associated with the city of Scarborough, England, now calling from the future. Its call is about romantic love, and also about a re-enchanted world, somewhere between the salt water and the sea strand, filled with parsley, sage, rosemary, and thyme.

In this imaginary land we recognize anew the preciousness of human life and also the aliveness of all things: the numinosity of rocks, for example. A featured columnist for Open Horizons, Patricia Adams Farmer, knows the rocks well, and gives us a sense of what re-enchanted eyes might see.

"The energy of rocks is particularly mysterious and primordial. I love to pick up a small rock from the wet sand and feel its warmth in my hand, even on chilly, sweatshirt days when the clouds hang low and the the volcanic sand cools my feet. A rock holds the energy of the sun long after everything around it succumbs to darkness and chill. The warm energy of the rock feels as if it were a living thing. And, in a sense, it is. And its “life” radiates a personality of something strong and trustworthy—and forever present in the world, remaining long after we are gone. The rock is very sure of itself, of its past and its future. And it has reason to be. When we pick up a rock, we are not just holding a lump of minerals: we are holding a piece of eternity in our hands." (Patricia Adams Farmer, The Numinosity of Rocks)

Imagine, then, a world where we hold rocks with respect for their numinosity and one another even more carefully. Such a world does not emerge all at once or even once and for all; but even mere approximations of it are worth dreaming. Such are the dreams of which God is made, and through which God is found. They are well worth the pilgrimage.

-- Jay McDaniel

Pilgrimage in Search

of Scarborough Fair

Magical Mystery Tour

|

A Walk Around Britain

|

Four Temptations of Folk Music

Falling into The Cult of Authenticity,

Adopting the Myth of a Perfect Past,

Succumbing to the Lure of Folk Nationalism

Valorizing Rural Life over the Urban Poor

There is a tendency among traditional folk music enthusiasts to see folk music as 'more authentic' than music produced commercially or in classical styles. I will call it hyper-romanticism. The hyper-romantics valorize what they understand to be "roots" music at the expense of urban music: hip-hop, rock, and electronic, for example. Traditional folk music comes to represent an idealized past which never really existed except in their minds: not unlike the politics of nostalgia in contemporary societies. (For more on this see Giving Up on Johnny Cash.) The sociologist Christopher Partridge points out these problems in The Lyre of Orpheus: Popular Music, the Sacred, and the Profane:

Despite differences of emphasis, central to an understanding of “folk culture” since the Romantics has been the notion of “authenticity.” Folk music, for example, is understood to be an authentic expression of a traditional, communal way of life, which may now be in the past or only accessible through the memories of a disappearing older generation. This type of thinking is conspicuous in the work of the principal collectors of folk music in the twentieth century, most notably Cecil Sharp... and the American folklorist and ethnomusicologist Alan Lomax. The latter, for example, argued that “the chief function of song is to express the shared feelings and mold joint activities of some human community.” Developing what was, in many ways, a Durkheimian sociology of music, Lomax understood the folk song style to symbolically represent the core elements of a culture, including its sacred forms. This is important because, if correct, it means that music is not of peripheral significance to societies, but rather primary, in that it functions as a way in which communities share values, communicate the sacred, and evoke a sense of belonging. While we will be returning to this argument later in the book, at this point it is the connection with the core elements of a culture that needs to be noted, for it is here where authenticity is located. Folk music functions as a symbolic representation of the true culture of “the folk,” who, by the time of Lomax, had become identified with the lower classes, the country workers, the “peasantry.” This understanding of the culture of “the people,” ideologically informed by the Romantic notion of an authentic culture of the nation, became very influential. It was, for example, notoriously persuasive in Germany during the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, informing a popular nationalism, a sacred system which eventually shaped an emerging Nazi ideology. As the late Nicholas Goodrick-Clarke discussed, the word “Volk” signified “much more than its straightforward translation ‘people’ to contemporary Germans; it denoted rather the national collectivity inspired by a common creative energy.… These metaphysical qualities were supposed to define the unique cultural essence of the German people.”

Partridge, Christopher (2013-10-21). The Lyre of Orpheus: Popular Music, the Sacred, and the Profane (p. 17). Oxford University Press, USA. Kindle Edition.

Enjoy the music, but avoid the cult of authenticity, the illusion of the idealized past, and the prejudice for "peasants" over the urban poor. Keep in mind that "folk music" is, among other things, a construction in the mind which can be healthy or unhealthy, truth-giving or truth-masking, depending on the context and the listener. And remember to enter into the arts of generous listening, where you listen to music you don't like, precisely in order to understand the world around you. Don't make a fetish of traditional folk music. Open yourself to the wider world -- the larger wheel of life -- beyond the comfort of the familiar.

Enjoy the music, but avoid the cult of authenticity, the illusion of the idealized past, and the prejudice for "peasants" over the urban poor. Keep in mind that "folk music" is, among other things, a construction in the mind which can be healthy or unhealthy, truth-giving or truth-masking, depending on the context and the listener. And remember to enter into the arts of generous listening, where you listen to music you don't like, precisely in order to understand the world around you. Don't make a fetish of traditional folk music. Open yourself to the wider world -- the larger wheel of life -- beyond the comfort of the familiar.

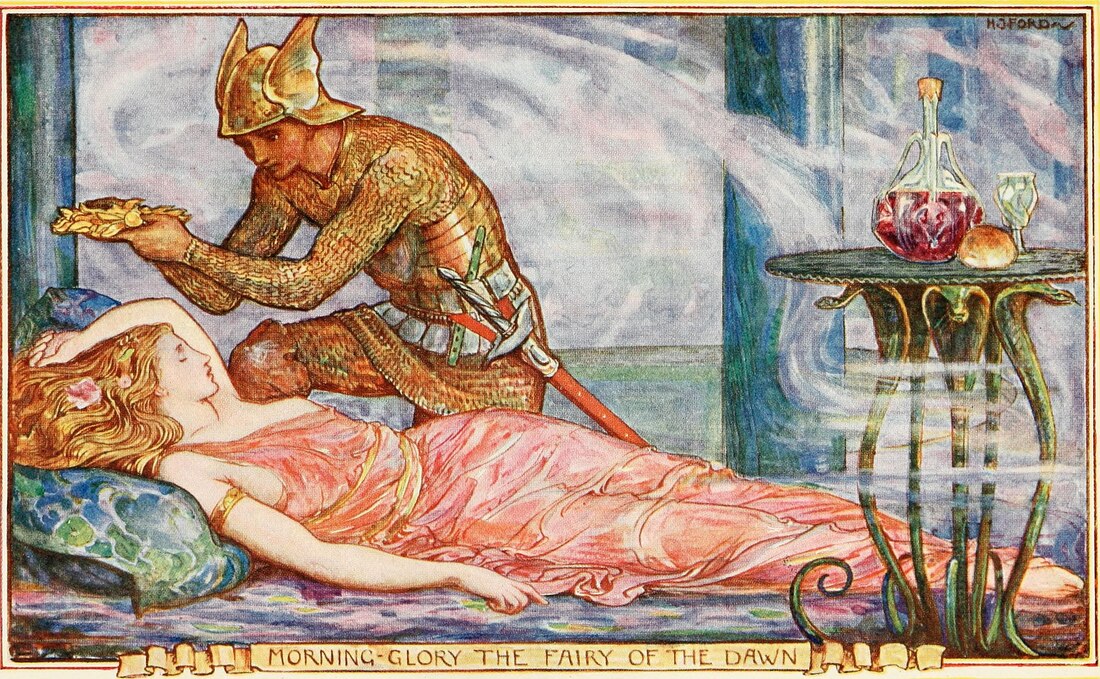

Ringlorn Fantasy

Wikipedia Commons

Wikipedia Commons

ringlorn

adj. the wish that the modern world felt as epic as the one depicted in old stories and folktales—a place of tragedy and transcendence, of oaths and omens and fates, where everyday life felt like a quest for glory, a mythic bond with an ancient past, or a battle for survival against a clear enemy, rather than an open-ended parlor game where all the rules are made up and the points don’t matter.

-- from the Dictionary of Obscure Sorrows