- Home

- Process Worldview

- Community

- Art and Music

- Whitehead and Process Thinking

- Podcasts

- Spirituality

- Ecological Civilization

- Education

- Contact

- Social Justice

- Science

- Animals

- Sacred Poems

- Whitehead Videos

- Index of All Titles

- Practicing Process Thought

- Process Spirituality: A Spiritual Alphabet

- Recent Posts

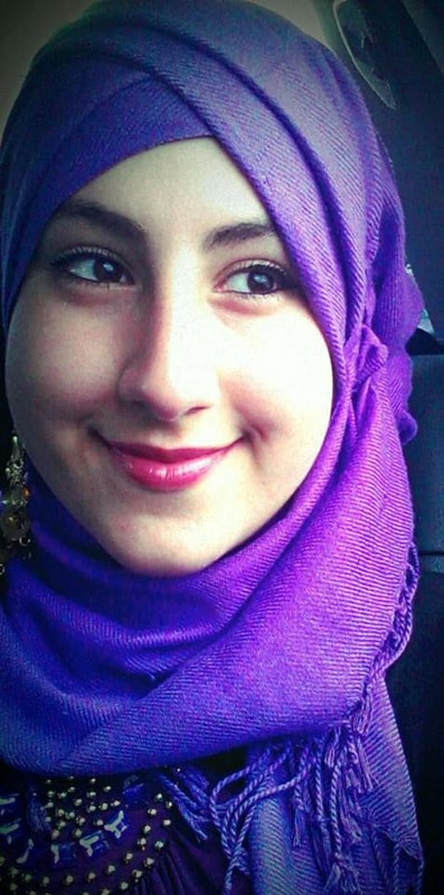

Asmaa Elamrousy: Hip Hop Hijabi

|

Creative Transformation after the Stereotypes Fall Away

As a Muslim who knows that God is always more than our concept of God, Asmaa Elamrousy understands. She knows that other people are always more than our concepts of them, too. Trust in God and relinquishing stereotypes are two sides of a single coin. At least this is how those of us influenced by process theology see things. We believe that God is a spacious receptacle for the whole universe in its delightful multiplicity and that this receptacle is a You who loves each person on our planet on her own terms and for her own sake. God is not merely a force at work in the nature of things, God is also a Love whom we can address in prayer and who beckons us into lives of creativity, wisdom, and compassion. This Love is not simply outside us. The love of God is also inside us as an indwelling lure to respect people as they are and as they are becoming, in their uniqueness, cognizant of the fact that they, like us, are beckoned by the lure of God to become themselves. In order to respect them in this way, the stereotypes we have of them must fall away, so that they can shine forth in their concreteness. When we see people through the lens of stereotypes we fall into the fallacy of misplaced concreteness. The fallacy of misplaced concreteness lies in confusing actual people with the stereotypes, and thinking that the stereotypes are themselves concrete. These stereotypes are not concrete at all. They are abstractions that have been foisted upon people by society and, sometimes, by themselves. The stereotypes may or may not contain a grain of truth in them, but never are they the whole of a person. A person is always more, much more, than the ideas we have of them or the ideas they have of themselves. When we forget this, we fall into the fallacy of misplaced concreteness. We get lost in our heads and the stereotypes we carry, and foreclose possibilities for being creatively transformed by the particularities of other people. We cannot see them or hear them on their own terms and for their own sakes. They become mere objects of our projections. If, for example, we carry in our minds abstractions concerning Arab-American youth, we may well confuse those abstractions with real persons of Arab American descent, each of whom is individual, and each of whom has his or her voice. Or perhaps better, voice-in-the-making. After all, no individual person is a completed or finished fact. Individual people are always on the way toward becoming who they can become. They are not simply speaking their voices, as if their voices were already defined; they are finding their voices, as are we all. Each age of a person’s life presents a new challenge, a new opportunity, for finding one’s voice. Your voice at age six is different from your voice at age sixteen, which is different from your voice at twenty-six, which is different from your voice at thirty-six. God is inside you all the time as a lure to find your voice, to speak your truth, to sing your song, to become yourself in the time at hand. At least this is how we process theologians think of God. God is not only an encompassing You in whose compassion we live and move and have our being; God is also a living spirit, inside us, beckoning us to become more fully ourselves, so that we can be carriers of divine love in the world. There’s more. If we carry stereotypes of others within our minds, God is in us as a call to let go of them, to relinquish abstractions in our minds, so that we can hear others on their own terms and for their own sakes. This call is unsettling, because we must relinquish ideas that may have given us a false sense of security. Indeed, the ideas may well have led us to divide the world into us and them, as if we are normal and even normative, and they are a bit different and maybe kind of wrong, because they belong to a different ethnic group, or religion, or political party. When we relinquish stereotypes, consciously and unconsciously, something almost magical happens inside us. We can call it grace, because it is a gift from the One who loves us, insofar as we cooperate with the inner promptings to let go. We are creatively transformed into wider selves, fatter souls, more hospitable hearts, and wiser minds. We can carry multiplicities in our minds and hearts, without reducing things to unanimity. We can embrace enriching tensions without pretending that everything must always be smooth. We can accept complexities without pretending everything is simple. We can become more fully ourselves, because someone else, a voice from elsewhere, has entered our lives, in all particularity, and said: “Here I am. Let's get to know each other. We can be friends.” O mankind, indeed We have created you from male and female and made you peoples and tribes that you may know one another. Indeed, the most noble of you in the sight of Allah is the most righteous of you. Indeed, Allah is Knowing and Acquainted. -- Qur'an 49:13 |

Frpm You Tube

Published on Nov 22, 2013 Meet Asmaa Elamrousy: Muslim. American. Rapper. Asmaa Elamrousy is a devout Muslim and Hijabi, covering herself from head to toe and hiding her hair under a headscarf tightly wrapped around her head. But there's more to her than meets the eye. She's also a rapper, who pounds her fist into the air demanding equality and international justice. "You shouldn't be scared or have fear of judgment," said Asmaa Elamrousy who tested her hustle and flow for an audience the first time at the annual Arab-Americans Got Talent competition. "You should say what's on your mind." Asmaa' is 19 years-old, born in Egypt and raised in Staten Island, New York where her interest in rap music stemmed from sibling rivalry of exchanging insults back and forth with her older brother Ahmed that escalated into rap battles. Ahmed then introduced Asmaa to her current idols Lupe Fiasco and Tupac Shakur, rappers whom she could identify with as Muslims who don't, as she puts it, just "rap about sex, money, drugs." "I'm not doing anything wrong, anything haram (forbidden)," explained Asmaa as she doesn't perform in bars and clubs that serve alcohol or objectify herself sexually, but she knows that some Muslims might still see what she is doing as wrong. "Hijabis are supposed to be quiet, they're not supposed to go out there and sing or rap, as there is a debate over the traditional saying "sawt al maraa awra (a woman's voice is exposing)." But Asmaa received a lot of community support at Brooklyn's second Arab Americans Got Talent competition, especially from last year's winner Omnia Hegazy, a singer/songwriter who says she faces such responses addressing critical issues from Arab communities publically, such as child marriage and women's rights. "They say well Arab Americans are discriminated against and you should be helping us look good, so let's deal with it within our own community," said Omnia who makes it a point to expose these issues and bring awareness to them. "But I think what makes us not look so great, is the fact that we ignore them." She hopes that more Arab-Americans, like Asmaa, will follow in her footsteps as a professional artist given that Arab-Americans are one of the least represented groups in the American music industry. Despite her take no prisoners attitude, Asmaa is currently battling with the idea of whether rap and music will stay a hobby or become a profession for her as she doesn't want to disappoint her parents. "They're supportive in a way," said Asmaa who wants to make sure they approve of her choices but at the same time show that hijabis can rap just as good as the men, if not better. "Anything a man can do, a woman can do it better.. I really believe that." Asmaa hopes to prove her claim one day by forming an all hijabi rap group. -- in Youtube |