Becoming an Interfaith Leader

A Collection of Resources for Students, Teachers,

Engaged Citizens and Community Builders

|

Might I, Too, be an Interfaith Leader?

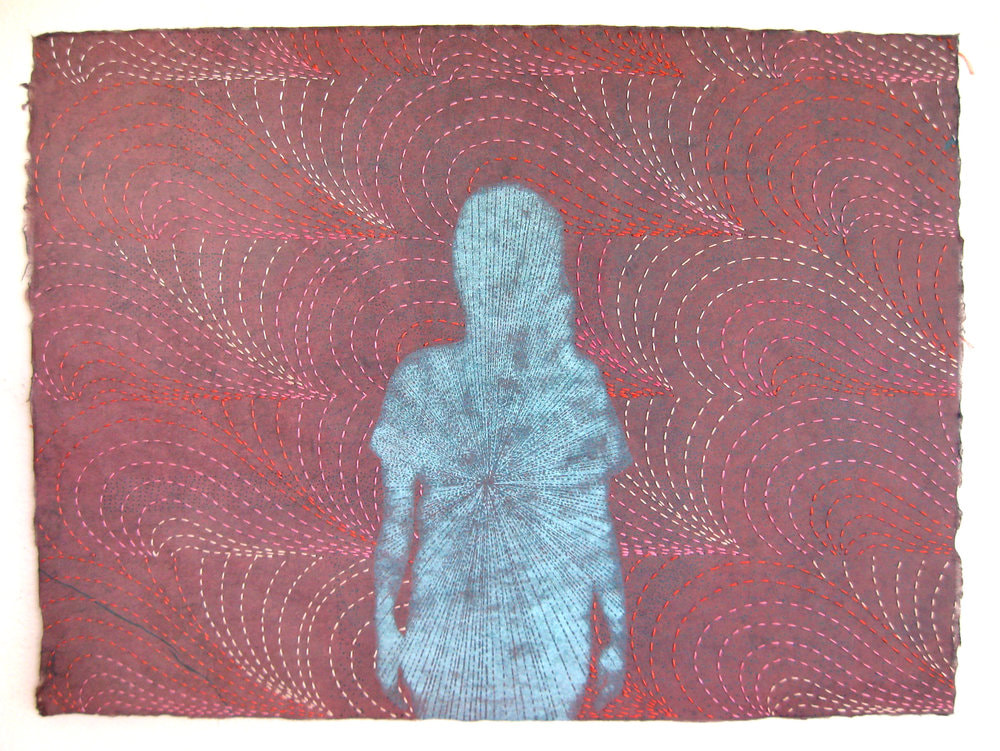

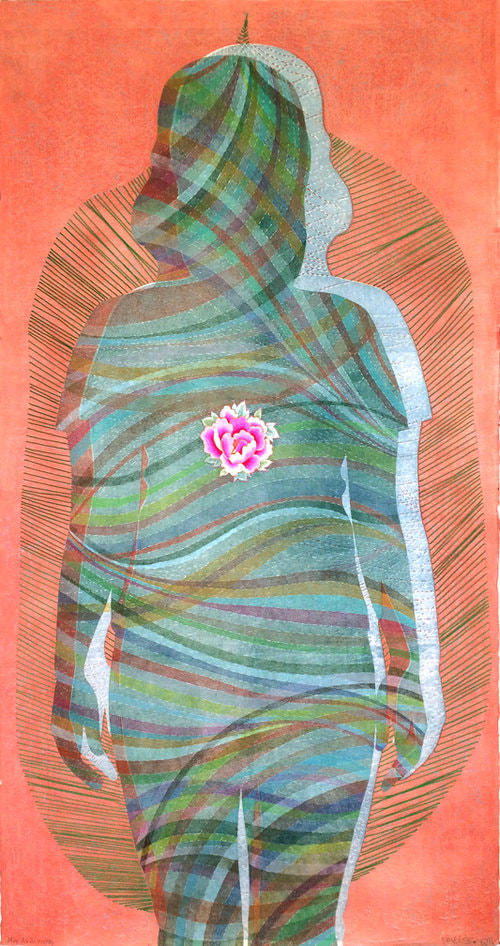

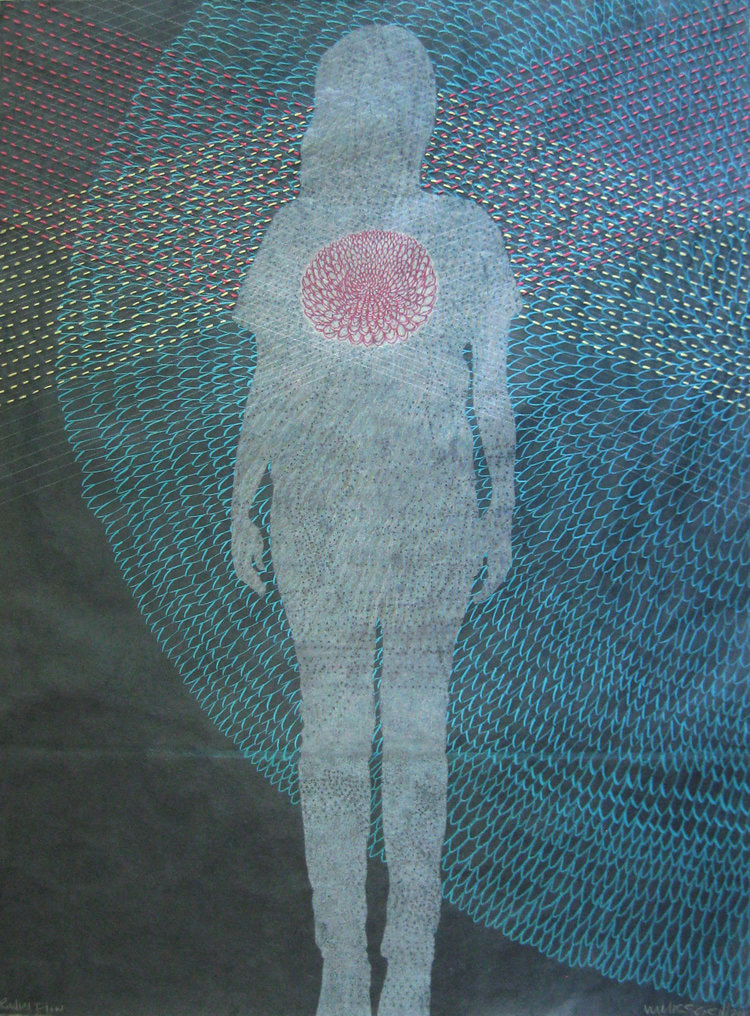

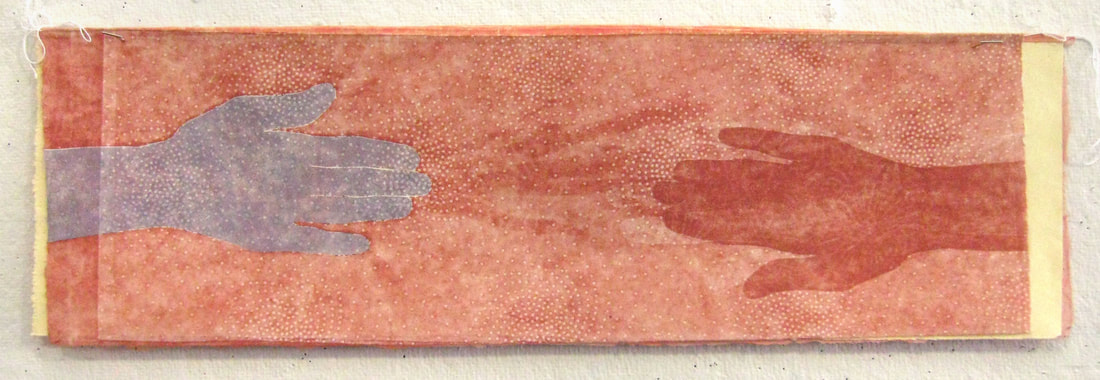

This page is a collection of resources for individuals and groups interested in exercising interfaith leadership in a multi-faith world. An interfaith leader is someone who helps build micro-bridges (friendships) and macro-bridges (vibrant interfaith communities) within and across religious differences. He or she can be a poet, schoolteacher, businessperson, police officer, chaplain, clergy person, barista, or politician. She is a bridge builder, no matter what. Interfaith community includes people who are affiliated with one or more of the world's institutional religions: Bahai, Buddhism, Christianity, Daoism, Islam, Judaism, Hinduism, Native Traditions, Paganism, Sikhism, Unitarian Universalism, for example. It also includes people without any affiliation: for example, secular humanists, atheists, people who are spiritually interested but not religiously affiliated. Humanists have a special role to play in interfaith work because they focus on life itself (human but also other forms of life) as a primary locus of value, reminding us that people's lives are always more than their affiliations, religious or otherwise. See How Can We Explore Questions of Purpose, Value, and Vocation in an Interfaith Context? and The Human Side of Interfaith. * If you feel drawn to exercise interfaith leadership, our hope is that this page offers some of the resources you need in order to do this work. Most of the material is drawn from the Interfaith Youth Core and the Harvard Pluralism Project, but some comes from other sources. We encourage you to use whatever is helpful in your context: public library, community center, classroom, coffee shop, church, synagogue, or mosque. If you would like a book to start your work, we recommend Interfaith Leadership: A Primer by Eboo Patel. Many of us interested in interfaith have used this book in the context of university teaching, along with the helpful videos offered below. If you are a faith leader, you may be interested in how a clergyperson approaches interfaith work. On this you might be interested in Rev. Teri Daily's Can I, Too, Be an Interfaith Leader? She is Christian priest in the Episcopal tradition, but her ideas speak to many in positions of religious leadership. Feel free to use the materials in a way that makes sense to you and speaks to your situation. And a special word of thanks to the Buddhist artist, Melissa Gill, for her artwork. -- Jay McDaniel |

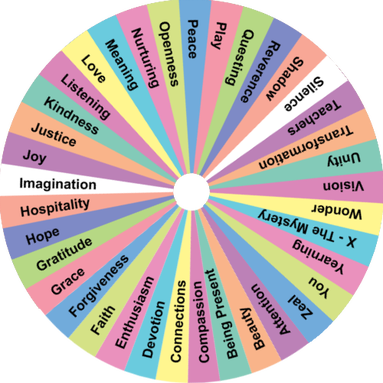

Wheel of Interfaith Spirituality

created by Jacob Turner, drawn from the work of Mary Ann and Fred Brussat in Spirituality and Practice

Selected Organizations and Links

Video Series from Interfaith Youth Core to help Train Interfaith Leaders

used in courses around the US

I. Introduction to Interfaith Leadership

2. Key Concepts of Interfaith Leadership

3. Identity of an Interfaith Leader

4. Cultivating Appreciative Knowledge

5. Historical Examples of Interfaith Cooperation

6. Ethics and Theologies of Interfaith Cooperation

7. The Movement Now

8. Leadership in Action

2. Key Concepts of Interfaith Leadership

3. Identity of an Interfaith Leader

4. Cultivating Appreciative Knowledge

5. Historical Examples of Interfaith Cooperation

6. Ethics and Theologies of Interfaith Cooperation

7. The Movement Now

8. Leadership in Action

| Discussion Questions and Activities for Videos |

|

|

|

|

Special Topics

Podcasts, Articles, Links

from IFYC and the Pluralism Project

Theological Addendum (only if helpful)

I have compiled this page for anyone and everyone who wants readily accessible, online resources for study groups in Interfaith Studies. My own hope is that readers from many faiths and no faith will use it, quite apart from religious affiliations. The practice of Pluralism is too important to be restricted by a single religious commitment. Nevertheless, I best admit that, among the many theologies available for incorporating interfaith studies in a larger context, I find process theology especially helpful

Process theology is an international, multifaith movement influenced by the organic cosmology of the philosopher Alfred North Whitehead. Process theologians come from a variety of backgrounds and combine aspects of Whitehead’s thought with wisdom from their own points of view. They are developing Christian process theologies, Jewish process theologies, Muslim process theologies, Buddhist process theologies, Hindu process theologies, Humanist process theologies, and more. Each form of process theology has its own unique coloration and emphases, but they also share some common ideas and values.

One of them is that the kind of interfaith literacy and cooperation developed by the Interfaith Youth Core is good in its own right and tremendously valuable in the world today. Indeed, the Interfaith Youth Core provides a vivid illustration of what it might mean to practice process theology from a given faith perspective.

Does the Interfaith Youth Core need process theology? Not necessarily. It needs whatever theologies dialogue partners might bring to the table of dialogue. But process theology might nevertheless be one of the voices at table. In what follows I offer some suggestions it might offer to the larger discussion.

Differences make the whole richer.

1. As people from different traditions enter into dialogue and cooperative relations, they can and should bring what is most important to them to the table. They don't have to leave their roots behind. Differences make the whole richer.

We are part of the Earth.

2. Interfaith dialogue can include a dialogue with the earth, because human life is nested within, not apart from the wider web of life. Environmental education and inter-faith dialogue can go hand in hand. All creatures have their own kind of spirituality. Subjectivity goes all the way down.

An essential need today is to build transition communities.

3. In an age of global climate change, one aim of interfaith dialogue and cooperation is to help build post-petroleum communities that are creative, compassionate, participatory, multi-religious and ecologically wise, with no one left behind. The common good of the world is not simply community, it is eco-community.

There may be many forms of ultimacy.

4. Different religions may highlight different features of reality as ultimately real (interconnectedness, the primacy of the present moment, the value of community, the reality of spirit worlds, the love of God). For one religion to be right, the others do not need to be wrong. They can be right about different things. The truths are many.

There may be many forms of salvation.

5. There may be different forms of salvation, corresponding to the diverse ultimates. One religion may highlight a form of well-being that emerges through an awakening to interconnectedness, another may highlight a form of well-being that emerges by accepting God's forgiving love, and still another may highlight a form of well-being that finds meaning in concourse with the spirits. Different religions do not need to have the same goals.

Religions are more than worldviews.

6. There is much more to religion than worldviews and beliefs. Religions include community, rituals, images, sounds, hopes, dreams, and stories. Sometimes it is these things -- not the worldviews -- that is most important to people.

We learn by listening.

7. We can bring to interfaith dialogue an appreciation of the role of the arts and music in dialogue, cognizant that, when it comes to knowing the religious other, there are many ways of knowing, including visual and musical and bodily knowing. Prayer and meditation are forms of knowing, too.

We can be transformed by what we hear.

8. One of the aims of dialogue, once trusted relations emerge, is mutual transformation, by which people internalize insights from the other and are transformed in the process.

Our capacities for empathy may be more than we know.

9. Human beings can feel the feelings of other human beings and take on their perspectives, even if they do not have shared histories or common backgrounds.

It's alright to critique one another, too.

10. Once trusted relations emerge, genuine dialogue can include mutual criticism and debate. In genuine dialogue it is alright to say "I disagree." Often we learn more from disagreements than agreements.

Self-critique is extremely important.

11. More important than critiquing others is self-critique. If we absolutize our inherited traditions (ritual and intellectual) and make gods of them, we miss the spirit of creative transformation. We have roots without wings.

We may need to reinvent our religions.

12. Religions are evolving through time, and they are never quire reducible to their inherited patterns and worldviews. Interfaith dialogue and cooperation provide opportunities for the creative development of world religions so they grow less violent, less arrogant, and more hospitable to life.

God is a lure toward dialogue and transformation.

13. The very desire for dialogue and widened horizons comes from a dimension of the universe itself -- a divine yearning -- that is present throughout the world as a spirit of creative transformation.

Interfaith cooperation as practicing the presence of God

14. When we are cooperating with others in respectful ways that help enrich the well-being of life on earth and in local communities, we are practicing the presence of God.

Process theology is an international, multifaith movement influenced by the organic cosmology of the philosopher Alfred North Whitehead. Process theologians come from a variety of backgrounds and combine aspects of Whitehead’s thought with wisdom from their own points of view. They are developing Christian process theologies, Jewish process theologies, Muslim process theologies, Buddhist process theologies, Hindu process theologies, Humanist process theologies, and more. Each form of process theology has its own unique coloration and emphases, but they also share some common ideas and values.

One of them is that the kind of interfaith literacy and cooperation developed by the Interfaith Youth Core is good in its own right and tremendously valuable in the world today. Indeed, the Interfaith Youth Core provides a vivid illustration of what it might mean to practice process theology from a given faith perspective.

Does the Interfaith Youth Core need process theology? Not necessarily. It needs whatever theologies dialogue partners might bring to the table of dialogue. But process theology might nevertheless be one of the voices at table. In what follows I offer some suggestions it might offer to the larger discussion.

Differences make the whole richer.

1. As people from different traditions enter into dialogue and cooperative relations, they can and should bring what is most important to them to the table. They don't have to leave their roots behind. Differences make the whole richer.

We are part of the Earth.

2. Interfaith dialogue can include a dialogue with the earth, because human life is nested within, not apart from the wider web of life. Environmental education and inter-faith dialogue can go hand in hand. All creatures have their own kind of spirituality. Subjectivity goes all the way down.

An essential need today is to build transition communities.

3. In an age of global climate change, one aim of interfaith dialogue and cooperation is to help build post-petroleum communities that are creative, compassionate, participatory, multi-religious and ecologically wise, with no one left behind. The common good of the world is not simply community, it is eco-community.

There may be many forms of ultimacy.

4. Different religions may highlight different features of reality as ultimately real (interconnectedness, the primacy of the present moment, the value of community, the reality of spirit worlds, the love of God). For one religion to be right, the others do not need to be wrong. They can be right about different things. The truths are many.

There may be many forms of salvation.

5. There may be different forms of salvation, corresponding to the diverse ultimates. One religion may highlight a form of well-being that emerges through an awakening to interconnectedness, another may highlight a form of well-being that emerges by accepting God's forgiving love, and still another may highlight a form of well-being that finds meaning in concourse with the spirits. Different religions do not need to have the same goals.

Religions are more than worldviews.

6. There is much more to religion than worldviews and beliefs. Religions include community, rituals, images, sounds, hopes, dreams, and stories. Sometimes it is these things -- not the worldviews -- that is most important to people.

We learn by listening.

7. We can bring to interfaith dialogue an appreciation of the role of the arts and music in dialogue, cognizant that, when it comes to knowing the religious other, there are many ways of knowing, including visual and musical and bodily knowing. Prayer and meditation are forms of knowing, too.

We can be transformed by what we hear.

8. One of the aims of dialogue, once trusted relations emerge, is mutual transformation, by which people internalize insights from the other and are transformed in the process.

Our capacities for empathy may be more than we know.

9. Human beings can feel the feelings of other human beings and take on their perspectives, even if they do not have shared histories or common backgrounds.

It's alright to critique one another, too.

10. Once trusted relations emerge, genuine dialogue can include mutual criticism and debate. In genuine dialogue it is alright to say "I disagree." Often we learn more from disagreements than agreements.

Self-critique is extremely important.

11. More important than critiquing others is self-critique. If we absolutize our inherited traditions (ritual and intellectual) and make gods of them, we miss the spirit of creative transformation. We have roots without wings.

We may need to reinvent our religions.

12. Religions are evolving through time, and they are never quire reducible to their inherited patterns and worldviews. Interfaith dialogue and cooperation provide opportunities for the creative development of world religions so they grow less violent, less arrogant, and more hospitable to life.

God is a lure toward dialogue and transformation.

13. The very desire for dialogue and widened horizons comes from a dimension of the universe itself -- a divine yearning -- that is present throughout the world as a spirit of creative transformation.

Interfaith cooperation as practicing the presence of God

14. When we are cooperating with others in respectful ways that help enrich the well-being of life on earth and in local communities, we are practicing the presence of God.