- Home

- Process Worldview

- Community

- Art and Music

- Whitehead and Process Thinking

- Podcasts

- Spirituality

- Ecological Civilization

- Education

- Contact

- Social Justice

- Science

- Animals

- Sacred Poems

- Whitehead Videos

- Index of All Titles

- Practicing Process Thought

- Process Spirituality: A Spiritual Alphabet

- Recent Posts

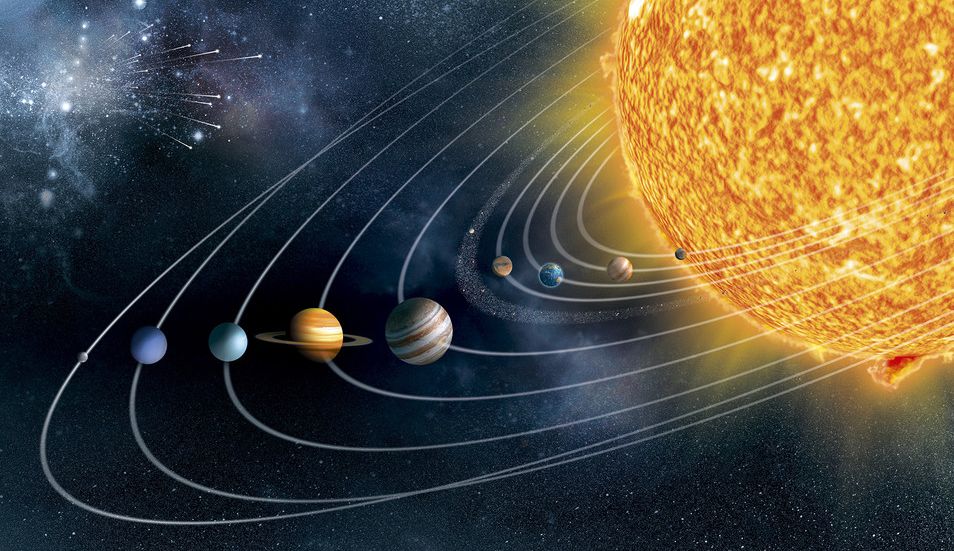

The Solar System as

Cosmic Neighborhood

Here we are, tucked away in a spiral arm of the Milky Way, orbiting a middle-aged star, with seven or eight planets joining us. We are fragile, confused, sometimes violent, sometimes loving, and often beautiful. We are also companions to kindred creatures who are equally beautiful. We are earthlings.

Never are we alone. Always we are parts of communities on Earth: families, cities, nations, landscapes, waterways, and bioregions. They are a part of who we are. We are relational earthlings, just like other plants and animals on our small planet.

Still, we are tucked within yet another community, the solar system, consisting of our host star, the Sun, and everything bound to it by gravity: the planets Mercury, Venus, Earth, Mars, Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, and Neptune; dwarf planets such as Pluto; dozens of moons; and millions of asteroids, comets, and meteoroids.

And that's not the whole of it. Beyond our own solar system, scientists have discovered thousands of additional planetary systems orbiting other stars in the Milky Way. And the Milky Way is but one of billions upon billions of galaxies, which, in all probability, likewise have thousands upon thousands of planetary systems. The vastness is fascinating and a little terrifying. Rudolph Otto described the experience of the "holy" as a mystery both attractive and frightening, The vastness is holy.

What to do? At the very least, we should befriend our own local solar community, cultivating an expanded sense of neighborhood. The planets are our neighbors. We should greet them, get to know them, and befriend them, without pretending that they are made in our image.

How to do this? Planetary astronomy helps us get to know them. It helps us greet our neighbors. Process theology, with its emphasis on relationality, both physical and emotional, and with its understanding of a Life in whom all systems unfold, provides a context.

- Jay McDaniel

Never are we alone. Always we are parts of communities on Earth: families, cities, nations, landscapes, waterways, and bioregions. They are a part of who we are. We are relational earthlings, just like other plants and animals on our small planet.

Still, we are tucked within yet another community, the solar system, consisting of our host star, the Sun, and everything bound to it by gravity: the planets Mercury, Venus, Earth, Mars, Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, and Neptune; dwarf planets such as Pluto; dozens of moons; and millions of asteroids, comets, and meteoroids.

And that's not the whole of it. Beyond our own solar system, scientists have discovered thousands of additional planetary systems orbiting other stars in the Milky Way. And the Milky Way is but one of billions upon billions of galaxies, which, in all probability, likewise have thousands upon thousands of planetary systems. The vastness is fascinating and a little terrifying. Rudolph Otto described the experience of the "holy" as a mystery both attractive and frightening, The vastness is holy.

What to do? At the very least, we should befriend our own local solar community, cultivating an expanded sense of neighborhood. The planets are our neighbors. We should greet them, get to know them, and befriend them, without pretending that they are made in our image.

How to do this? Planetary astronomy helps us get to know them. It helps us greet our neighbors. Process theology, with its emphasis on relationality, both physical and emotional, and with its understanding of a Life in whom all systems unfold, provides a context.

- Jay McDaniel

Ten Gifts from the Planets

We living beings on Earth are not alone in orbiting the Sun. Other planets have their own unique solar dances. We join them in a celestial choreography, each planet with our unique qualities and orbits, coordinated with one another in various ways. The other planets are strange and beautiful, independent from us in many ways, and also our co-dancers, our material kin, our kindred pilgrims, and our neighbors. If God is a lure toward ordered forms of novelty and novel forms of order, God is about all the communities, not just our own.

For most of human history, people have believed that the movements of other planets are related to their destinies on Earth. These movements need not control destinies, but they influence destinies. If you believe that everything is interconnected, then this perspective makes sense. Just as aspects of life are influenced by the tides and gravity from the moon, so perhaps aspects are influenced by movements of the planets. Hence the wisdom, or at least the plausibility, of astrology, a field of interest much maligned by many. Let there be more openness to multiple sources of wisdom.

Nevertheless, astronomy too has much to offer, and that is my focus in this essay. As we learn more and more from astronomy, our imaginations are tweaked and stimulated. Planets are objects in the heavens and, to use Whitehead's phrase, "lures for feeling." We learn about them and from them. Both forms of learning are important. These two forms of learning, both prompted by astronomy, occur together, for scientists and non-scientists alike. Astronomers would not undertake their research if they were not amazed, as are we all, by the beauty and strangeness of other planets: their beautiful otherness and the sheer fact of outer space. In its science no less than its poetry, astronomy is an attempt to befriend this otherness through understanding.

Jared Morningstar, a process philosopher, understands "understanding" as a form of intimacy. For him, intimacy includes but is not limited to bodily touch. It is taking on the perspective of another, either by imagining yourself inside it or, as is the case in planetary astronomy, gathering information about the Other in a way that respectfully lets the Other speak.

Planetary astronomy is a way of letting planets speak without pretending to be inside them. The instruments of planetary astronomy are visual telescopes, radio telescopes, spectrometers, cameras, and other forms of imaging equipment, radar systems, computer modeling and simulation, spacecraft, and probes for understanding the uniqueness of planets. They are extensions of our human senses, and they help astronomers explore, and thus touch, planetary bodies. The touch is conceptual, to be sure, but also poetic and imaginative. Scientists are whole persons. The aim of such touch is not conquest but rather, as Morningstar says, "intimacy." It is to be with something other and, as it were, befriend it.

Of course, science is but one way of knowing. The instruments just named are complemented by other forms of knowing that can be inspired by the planets: poetic, mythical, imaginative, and musical. With help from these instruments, the planets become our teachers, perhaps even our spiritual guides, in at least ten ways. Here are some gifts of our planetary neighbors:

- They provide an expanded sense of place: The planets of our solar system remind us that the living Earth is part of larger systems (in this case, solar systems), giving us a sense of our place in the larger scheme of things. They challenge Earthism when it becomes idolatrous.

- They are invitations to humility: The planets invite a sense of humility, acknowledging that we are not the center of the universe or even the solar system. They de-center us in healthy ways. They serve as a reminder that there may well be life on other planets, both within our solar system and in planets around other solar systems in other galaxies.

- They offer touches of transcendence: The planets offer a touch of transcendence, as described by theologian Maya Rivera, allowing us to glimpse something beyond ourselves through the face of another—specifically, the face of a planet. Already we receive these "touches" in the presence of other people, landscapes, and waterways; the planets offer an additional and unique touch.

- They are catalysts for wonder: The planets inspire wonder and imagination, which are fundamental spiritual emotions for a fulfilling life. The planets inspire imagination both scientifically and mythically. Scientifically, they spur adventures in research and understanding, including the impulse to probe space in spacecraft. Mythically, they offer images for poets, science fiction writers, musicians, and "regular" people who need homes away from home.

- They expand our understanding of God: The planets expand our idea of God, so that we learn to think in less earth-absolutizing ways. We remember that the solar system is part of God's life, not just our small planet, and that God is present in and to other planets. They are present in and to God. And we realize that if God is indeed a lure toward becoming within each existent, God is a lure toward becoming in all planets, not just our own.

- They are homes away from home: Sun Ra, the American jazz musician and bandleader, often said he was born on Saturn and often incorporated cosmic and science fiction themes into his music and persona. His birth name was Herman Poole Blount, and records suggest he was born on Earth in Birmingham, Alabama, United States, on May 22, 1914. Literalists see the Alabama birth as "true" and the Saturn birth as playfully "fictional." But Saturn functioned for Sun Ra as a home away from home. It was, for him, as literally true, and perhaps more so, than much of what he knew on Earth.

- They are invitations to think beyond property: The planets remind us that we do not need to own things. They remind us that true friends are not owned, as they have their own autonomy and existence. In their transcendence, they possess their own integrity and cannot be reduced to mere possessions.

- They are invitations to think beyond nation: The planets transcend national boundaries and remind us that we are part of a larger cosmic community. They challenge our narrow perspectives and encourage us to think beyond the limitations of national identities. They inspire a sense of unity and interconnectedness among all Earth's inhabitants.

- They are invitations to think beyond religion: The planets offer a perspective that extends beyond any particular religious beliefs or dogmas. They remind us that the mysteries of the universe are not confined to any single religious framework. They invite us to explore the wonder and awe of the cosmos, transcending religious boundaries and embracing a broader understanding of the divine.

- They are, or can be, invitations to love the Earth: The planets can invite us to better realize the fragility and beauty of life on Earth, loving it more dearly as a unique habitat for the kinds of life that we rightly hold dear. Even as they are homes away from home, we can sense the preciousness, the uniqueness, of our home. Just because other homes are beautiful doesn't mean that our home can't be beautiful too.

Back, then, to God. I have said that getting to know other planets affords an expanded understanding of God. It also affords an expanded understanding of revelation. It is all too easy for human beings to think of revelation as occurring primarily in texts (Torah, the Bible, the Qur'an, the Bhagavad Gita, the Dao de Jing) or in the natural world (hills, rivers, trees, animals, and plants) or in terrestrial relationships, human to human and human to earth. The planets are revelations, too. They remind us ever so vividly that we are not alone in the universe and that the lure of God is by no means limited to life on Earth.

- Jay McDaniel

Greeting our Neighbors

with help from BBC

The Planets

Melvyn Bragg and guests discuss our knowledge of the planets in both our and other solar systems. Tucked away in the outer Western Spiral arm of the Milky Way is a middle aged star, with nine, or possibly ten orbiting planets of hugely varying sizes. Roughly ninety-two million miles and third in line from that central star is our own planet Earth, in thrall to our Sun, just one of the several thousand million stars that make up the Galaxy.Ever since Galileo and Copernicus gave us a scientific model of our own solar system, we have assumed that somewhere amongst the myriad stars there must be other orbiting planets, but it took until 1995 to find one. ‘51 Pegasus A’ was discovered in the Pegasus constellation and was far bigger and far closer to its sun than any of our existing theories could have predicted. Since then 121 new planets have been found. And now it is thought there may be more planets in the skies than there are stars.What causes a planet to form? How do you track one down? And how likely is there to be another one out there with properties like the Earth’s?

With Paul Murdin, Senior Fellow at the Institute of Astronomy in Cambridge;

Hugh Jones, planet hunter and Reader in Astrophysics at Liverpool John Moores University;

Carolin Crawford, Royal Society Research Fellow at the Institute of Astronomy in Cambridge.

Venus

Melvyn Bragg and guests discuss the planet Venus which is both the morning star and the evening star, rotates backwards at walking speed and has a day which is longer than its year. It has long been called Earth’s twin, yet the differences are more striking than the similarities. Once imagined covered with steaming jungles and oceans, we now know the surface of Venus is 450 degrees celsius, and the pressure there is 90 times greater than on Earth, enough to crush an astronaut. The more we learn of it, though, the more we learn of our own planet, such as whether Earth could become more like Venus in some ways, over time.

With

Carolin Crawford

Public Astronomer at the Institute of Astronomy and Fellow of Emmanuel College, University of Cambridge

Colin Wilson

Senior Research Fellow in Planetary Science at the University of Oxford

And

Andrew Coates

Professor of Physics at Mullard Space Science Laboratory, University College London

Produced by: Simon Tillotson and Julia Johnson

With

Carolin Crawford

Public Astronomer at the Institute of Astronomy and Fellow of Emmanuel College, University of Cambridge

Colin Wilson

Senior Research Fellow in Planetary Science at the University of Oxford

And

Andrew Coates

Professor of Physics at Mullard Space Science Laboratory, University College London

Produced by: Simon Tillotson and Julia Johnson

Mars

Melvyn Bragg and guests discuss the planet Mars. Named after the Roman god of war, Mars has been a source of continual fascination. It is one of our nearest neighbours in space, though it takes about a year to get there. It is very inhospitable with high winds racing across extremely cold deserts. But it is spectacular, with the highest volcano in the solar system and a giant chasm that dwarfs the Grand Canyon.For centuries there has been fierce debate about whether there is life on Mars and from the 19th century it was even thought there might be a system of canals on the planet. This insatiable curiosity has been fuelled by writers like HG Wells and CS Lewis and countless sci-fi films about little green men.So what do we know about Mars – its conditions, now and in the past? What is the evidence that there might be water and thus life on Mars? And when might we expect man to walk on its surface?

With

John Zarnecki, Professor of Space Science at the Open University and a team leader on the ExoMars mission;

Colin Pillinger, Professor of Planetary Sciences at the Open University and leader of the Beagle 2 expedition to Mars;

Monica Grady, Professor of Planetary and Space Sciences at the Open University and an expert on Martian meteorites.

Saturn

Melvyn Bragg and guests discuss the planet Saturn with its rings of ice and rock and over 60 moons. In 1610, Galileo used an early telescope to observe Saturn, one of the brightest points in the night sky, but could not make sense of what he saw: perhaps two large moons on either side. When he looked a few years later, those supposed moons had disappeared. It was another forty years before Dutch scientist Christiaan Huygens solved the mystery, realizing the moons were really a system of rings. Successive astronomers added more detail, with the greatest leaps forward in the last forty years. The Pioneer 11 spacecraft and two Voyager missions have flown by, sending back the first close-up images, and Cassini is still there, in orbit, confirming Saturn, with its rings and many moons, as one of the most intriguing and beautiful planets in our Solar System.

With

Carolin Crawford

Public Astronomer at the Institute of Astronomy and Fellow of Emmanuel College, University of Cambridge

Michele Dougherty

Professor of Space Physics at Imperial College London

And

Andrew Coates

Deputy Director in charge of the Solar System at the Mullard Space Science Laboratory at UCL.

With

Carolin Crawford

Public Astronomer at the Institute of Astronomy and Fellow of Emmanuel College, University of Cambridge

Michele Dougherty

Professor of Space Physics at Imperial College London

And

Andrew Coates

Deputy Director in charge of the Solar System at the Mullard Space Science Laboratory at UCL.

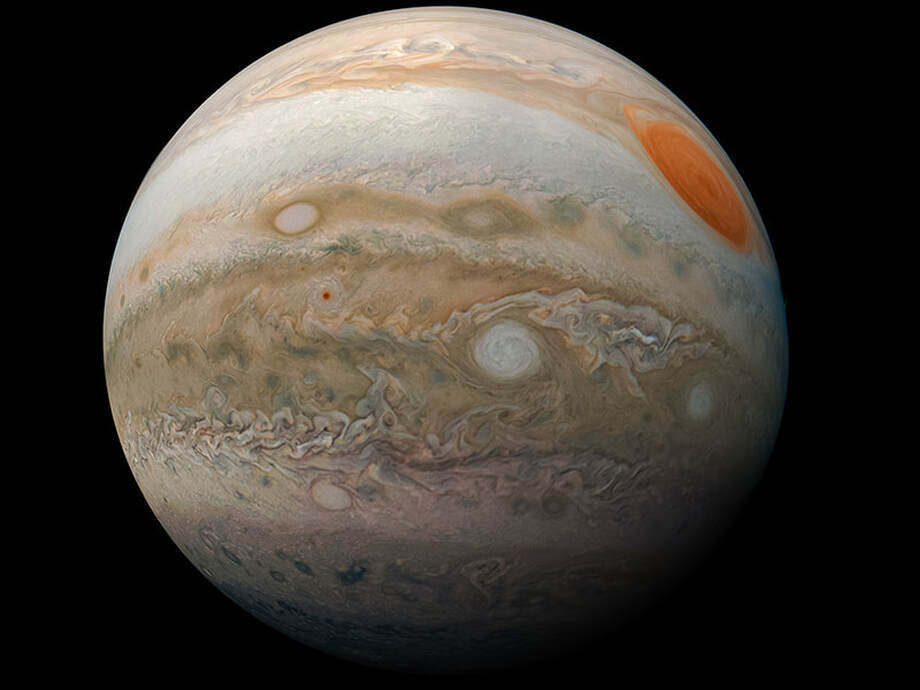

Jupiter

Jupiter is the largest planet in our solar system, and it’s hard to imagine a world more alien and different from Earth. It’s known as a Gas Giant, and its diameter is eleven times the size of Earth’s: our planet would fit inside it one thousand three hundred times. But its mass is only three hundred and twenty times greater, suggesting that although Jupiter is much bigger than Earth, the stuff it’s made of is much, much lighter. When you look at it through a powerful telescope you see a mass of colourful bands and stripes: these are the tops of ferocious weather systems that tear around the planet, including the great Red Spot, probably the longest-lasting storm in the solar system. Jupiter is so enormous that it’s thought to have played an essential role in the distribution of matter as the solar system formed – and it plays an important role in hoovering up astral debris that might otherwise rain down on Earth. It’s almost a mini solar system in its own right, with 95 moons orbiting around it. At least two of these are places life might possibly be found.

With

Michele Dougherty, Professor of Space Physics and Head of the Department of Physics at Imperial College London, and principle investigator of the magnetometer instrument on the JUICE spacecraft (JUICE is the Jupiter Icy Moons Explorer, a mission launched by the European Space Agency in April 2023)

Leigh Fletcher, Professor of Planetary Science at the University of Leicester, and interdisciplinary scientist for JUICE

Carolin Crawford, Emeritus Fellow of Emmanuel College, University of Cambridge, and Emeritus Member of the Institute of Astronomy, Cambridge

With

Michele Dougherty, Professor of Space Physics and Head of the Department of Physics at Imperial College London, and principle investigator of the magnetometer instrument on the JUICE spacecraft (JUICE is the Jupiter Icy Moons Explorer, a mission launched by the European Space Agency in April 2023)

Leigh Fletcher, Professor of Planetary Science at the University of Leicester, and interdisciplinary scientist for JUICE

Carolin Crawford, Emeritus Fellow of Emmanuel College, University of Cambridge, and Emeritus Member of the Institute of Astronomy, Cambridge

Appendix: About Moons

The "traditional" moon count most people are familiar with stands at 290: One moon for Earth; two for Mars; 95 at Jupiter; 146 at Saturn; 27 at Uranus; 14 at Neptune; and five for dwarf planet Pluto. According to NASA/JPL's Solar System Dynamics team, astronomers have documented more than 460 natural satellites orbiting smaller objects, such as asteroids, other dwarf planets, or Kuiper Belt Objects (KBOs) beyond the orbit of Neptune.

Moons come in many shapes, sizes, and types. A few have atmospheres and even hidden oceans beneath their surfaces. Most planetary moons probably formed from the discs of gas and dust circulating around planets in the early solar system, though some are captured objects that formed elsewhere and fell into orbit around larger worlds.

Scientists are getting so good at spotting tiny moons orbiting distant, giant planets that the International Astronomical Union, which governs official names of planets and moons, will no longer name the smallest moons unless they’re of “significant” scientific interest. There are likely thousands more moons awaiting discovery in our solar system.

Moons come in many shapes, sizes, and types. A few have atmospheres and even hidden oceans beneath their surfaces. Most planetary moons probably formed from the discs of gas and dust circulating around planets in the early solar system, though some are captured objects that formed elsewhere and fell into orbit around larger worlds.

Scientists are getting so good at spotting tiny moons orbiting distant, giant planets that the International Astronomical Union, which governs official names of planets and moons, will no longer name the smallest moons unless they’re of “significant” scientific interest. There are likely thousands more moons awaiting discovery in our solar system.