Whose Flesh is it Anyway?

Theological Reflections while Strolling through

the Body of Empathy Exhibition

The Body of Empathy is an internationally juried show of environmental portrait paintings by six different artist: Donna Festa, Karen Fleming, Nina Jordan, Eva O'Donovan, Emily McIlroy, and Niamh McGuinne. The yearlong show is jointly curated by Professor Mathew Lopas and Dr. James Dow. The theme of The Body of Empathy is whether we can empathize with characters or persons in paintings. Can looking at the human body in a painting be a type of ethical witnessing of the life of a person? How does engagement with paintings cultivate empathy differently than perspective taking with people?

|

Niamh McGuinne, Wilgefortis, 2018Thermal Transfer Screen Print and Encaustic on Aluminum 42cm x 35cm

Donna Festa, Happy Birthday Evie Smith, 2012, Oil on Panel, 6in x 6in

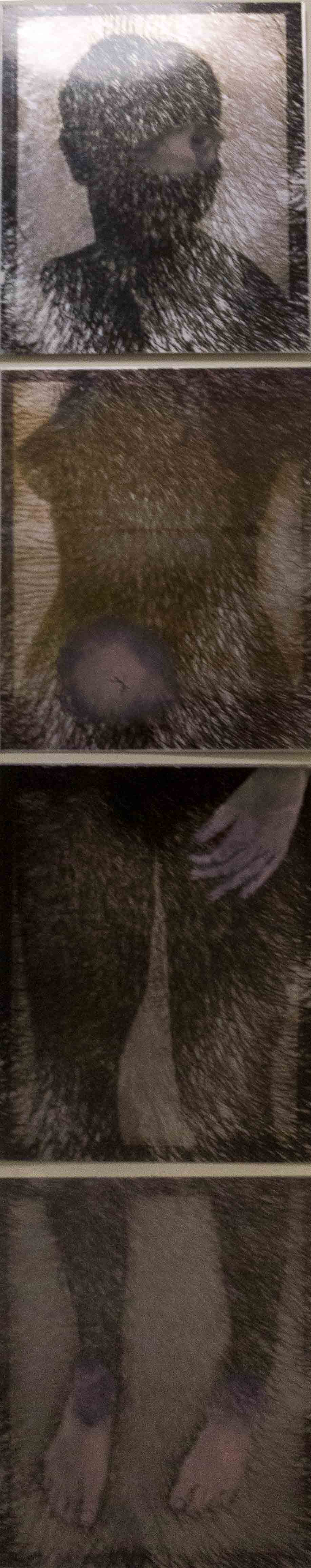

Emily McIlroy, Memory: Autopsy, 2014, Oil and Black Pastel on Paper52in x 33in

|

Thinking about FleshFlesh is always becoming. Air, water, food, sunlight, and even societies of microorganisms enter our bodies to weave the delicate tissue of our flesh. Imperceptibly to the naked eye, cell by cell, day after day, the world constitutes your body and mine. And our bodies enter into the constitution of the world. They are intimately our own, singular and irreplaceable, and yet formed by and given to the world. (Mayra Rivera, Poetics of the Flesh)

The flesh is that which connects you to the world, but with that connection comes the vulnerability of being shaped by the world... Part of what I want to see in flesh is vitality. What are the possibility of people imagining different realities, different ways of constituting the world, so that their own bodies can develop, can flourish in ways they have not been allowed to flourish. The flourishing of the person is tied to the flourishing of the community. (Mayra Rivera, Poetics of the Flesh) Whose Flesh is it, Anyway?

Who said theology can't be communicated in art? Thanks to the work of James Dow and Matthew Lopas, a year-long art exhibit begins at Hendrix College on the Body of Empathy, and to my mind the exhibit builds a bridge between spirituality, philosophy, and theology. The exhibition is an internationally juried show of environmental portrait paintings by six different artist: Donna Festa, Karen Fleming, Nina Jordan, Eva O'Donovan, Emily McIlroy, and Niamh McGuinne.

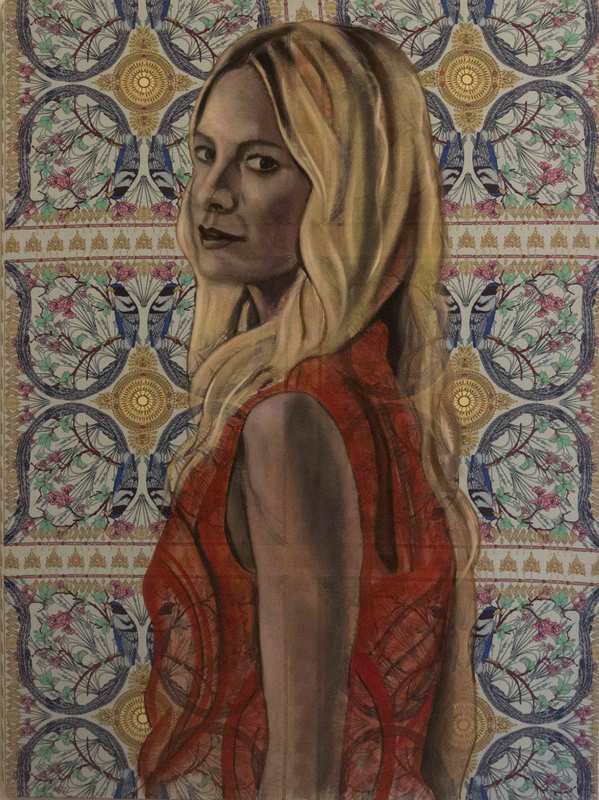

For my part I think "theologically" as a view the exhibition, and if you're in the same situatiion I have a suggestion. Assume for the sake of discussion that empathy is feeling the feelings of another human being, another animal, or (so process theologians would propose) the soul -- the embodied mind -- of the universe, sometimes named God, whose very body is the universe itself. And imagine further, for the sake of discussion, that the embodied mind is, as Buddhists might say, a combination of deep wisdom and unbounded compassion. In the latter respect the mind might be called cosmic Empathy or deep Empathy, with upper case letters, signifying the fact that the deep Empathy feels the feelings of all sentient beings, humans much included, with, in Whitehead's words, a "tender care that nothing be lost." The deep Empathy can be named "God" or "Guan Yin" or "The Great Compassion" -- and of course it need not be named at all. But let's recognize still further that we humans can only participate in this empathy fleetingly and partially. On the one hand we are made in the image of the Empathy -- so we learn from Buddhism with its idea of the image of the Buddha Nature within each of us, and from Judaism, Christianity, and Islam with their idea of the image of God within each of us. Indeed we learn something of this image by means of evolutionary biology, with its studies of how and why we carry capacities for empathy and altruism. Nevertheless, we are made in other images, too, which also have their evolutionary antecedents: hatred, greed, indifference, confusion, tribalism, fear of the stranger. These impulses, too, are part of our makeup. The question then emerges, might some forms of art help us grow in our capacities for empathy, avoid the liabilities of the other forms, and thus better participate in the deep Empathy, if we find the idea meaningful. Of course other things besides art come to might help as well: concrete acts of lovingkindness, for example, in which we so often learn what others feel not by reflection but by immersion. And music, too, introduces us to the emotional ranges of human life because, after all, music is what feelings sound like. But visual art of the kind found in the Body of Empathy exhibition, in its sheer presence to us, can likewise inspire our capacities for empathy, if we are present to it in mindful ways. Our mindful presence to the art is very important: we must sit with it, without being hurried, for much more than a few seconds, and let it speak to us on its terms. We must avoid interpreting or analyzing it too quickly. We must rest in what classical theologians called the apophatic way: the way of "unknowing" where our categories drop away and we let the other speak on her terms, on his terms, in ways that leave us speechless. In their speaking to us, we partake of what Harvard theologian Mayra Rivera calls a touch of transcendence. What transcends us in this case is not the embodied mind of the universe, but also, and more importantly, the other person who gazes back at us, or away from us, in her own embodied way. Yes, the body of the other is canvas on which flesh is depicted, not flesh itself. But for that very reason the flesh has a capacity to speak to us more directly, in almost archetypal form, saying: "Here I am, in my ambiguity, in my suffering, in my confusion, in my resistance to your consuming me with your imposed frameworks." As this happens the painting itself becomes a koan, a question, a claim made upon us by, in the words of Emmanuel Levinas, the "face of the other." As the claim is made, and we receive it, we partake of the deep Empathy, thus recognized or not. This is the theological side of the Body of Empathy. It is not simply what we see, but how we see, with a surrender to the image, with a relinquishing of the categorizing mind, with an inner voice which says to us, from the other side of our skin, "I, too, am alive. I, too, count." -- Jay McDaniel Eva O'Donovan, Emma, 2018, Oil on Printed Fabric, 35in x 45in

|