A Grateful Day and Loving Your Enemies

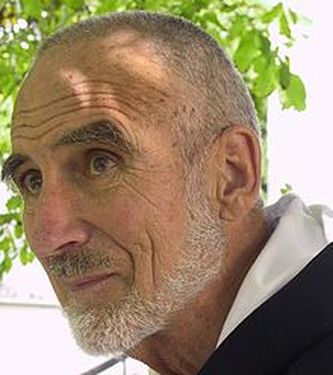

BR. DAVID STEINDL-RAST, OSB

|

David Steindl-Rast OSB (born July 12, 1926) is a Catholic Benedictine monk, notable for his active participation in interfaith dialogue and his work on the interaction between spirituality and science.

|

A Grateful Day

“Love Your Enemies!” What Does It Mean? Can It Be Done?

BY BR. DAVID STEINDL-RAST, OSB

To love our enemies does not mean that we suddenly become their friends. If it is our enemies we are to love, they must remain enemies. Unless you have enemies, you cannot love them. And if you have no enemies, I wonder if you have any friends. The moment you choose your friends, their enemies become your own enemies. By having convictions, we make ourselves the enemies of those who oppose these convictions. But let’s be sure we agree on what we mean by terms like Friend, Enemy, Hatred, or Love.

The mutual intimacy we share with our best friends is one of the greatest gifts of life, but it is not always given when we call someone a friend. Friendship need not even be mutual. How about organizations like Friends of Our Local Library? Friends of Elephants and of other endangered species? Friendship allows for many degrees of closeness and takes many different forms. What it always implies is active support of those whom we befriend, engagement to help them reach their goals.

With enemies it is the exact opposite. After all, the very word “enemy” comes from the Latin ”inimicus”, and means simply “not a friend”. Of course, not everyone who is not a friend is therefore an enemy. Enemies are opponents – not opponents for play, as in sports or games, but in mutual opposition with us in matters of deep concern. Their goals are opposed to our own highest aspirations. Thus, out of conviction we must actively try to prevent them from reaching their goals. We can do this lovingly, or not – and thus we find ourselves head-on confronted with the possibility to love of enemies.

Love makes us first of all think of romantic attraction, affection and desire – a whirlwind of emotions, yes, but that is only one of countless forms in which we experience love. In so many different contexts do we speak of love that one may actually wonder what they have in common, if anything: Love between teacher and pupil, love of parents for children, of children for parents; love of your dog or your cats, your country, your grandparents. Again, how different our love for a grandmother is from that for a grandfather and both of them from love for a pet geranium among our potted plants, let alone love for a sweetheart. Is there a common denominator for all these varieties of love? Yes, indeed, there is.

Love in every one of its forms is a lived “yes” to belonging. I call it a “lived yes”, because the very way loving people live and act says loudly and clearly: “Yes, I affirm and respect you and I wish you well. As members of the cosmic family we belong together, and this belonging goes far deeper than anything that can ever divide us.” In an upside-down way, a “Yes” to belonging is even present in hatred. While love says this yes joyfully and with fondness, hatred says it grudgingly with animosity, gall. Still, even one who hates acknowledges mutual belonging. Have there not been moments in your life when you couldn’t say whether you loved or hated someone close to your heart? This shows that hatred is not the opposite of love. The opposite of love (and of hatred) is indifference.

How, then, can we go about loving our enemies?

The mutual intimacy we share with our best friends is one of the greatest gifts of life, but it is not always given when we call someone a friend. Friendship need not even be mutual. How about organizations like Friends of Our Local Library? Friends of Elephants and of other endangered species? Friendship allows for many degrees of closeness and takes many different forms. What it always implies is active support of those whom we befriend, engagement to help them reach their goals.

With enemies it is the exact opposite. After all, the very word “enemy” comes from the Latin ”inimicus”, and means simply “not a friend”. Of course, not everyone who is not a friend is therefore an enemy. Enemies are opponents – not opponents for play, as in sports or games, but in mutual opposition with us in matters of deep concern. Their goals are opposed to our own highest aspirations. Thus, out of conviction we must actively try to prevent them from reaching their goals. We can do this lovingly, or not – and thus we find ourselves head-on confronted with the possibility to love of enemies.

Love makes us first of all think of romantic attraction, affection and desire – a whirlwind of emotions, yes, but that is only one of countless forms in which we experience love. In so many different contexts do we speak of love that one may actually wonder what they have in common, if anything: Love between teacher and pupil, love of parents for children, of children for parents; love of your dog or your cats, your country, your grandparents. Again, how different our love for a grandmother is from that for a grandfather and both of them from love for a pet geranium among our potted plants, let alone love for a sweetheart. Is there a common denominator for all these varieties of love? Yes, indeed, there is.

Love in every one of its forms is a lived “yes” to belonging. I call it a “lived yes”, because the very way loving people live and act says loudly and clearly: “Yes, I affirm and respect you and I wish you well. As members of the cosmic family we belong together, and this belonging goes far deeper than anything that can ever divide us.” In an upside-down way, a “Yes” to belonging is even present in hatred. While love says this yes joyfully and with fondness, hatred says it grudgingly with animosity, gall. Still, even one who hates acknowledges mutual belonging. Have there not been moments in your life when you couldn’t say whether you loved or hated someone close to your heart? This shows that hatred is not the opposite of love. The opposite of love (and of hatred) is indifference.

How, then, can we go about loving our enemies?

- Show your enemies the genuine respect that every human being deserves. Learn to think of them with compassion.

- In cultivating compassion, it may help to visualize your enemies as the children they once were (and somehow remain).

- Do not dispense compassion from above, but meet your enemies in your imagination always at eye-level.

- Make every effort to come to know and understand them better – their hopes, their fears, concerns, and aspirations.

- Search for common goals, spell them out, and try to explore together ways of reaching these goals.

- Don’t cling to your own convictions. Examine them in light of your enemies’ convictions with all the sincerity you can muster.

- Invite your enemies to focus on issues. While focusing on the issues at hand, suspend your convictions.

- Do not judge persons, but look closely at the effect of their actions. Are they building up or endangering the common good?

- Take a sober look at your enemies’ goals and evaluate them with fairness. If necessary, block them decisively.

- In order to counteract your enemies effectively on a given issue, join the greatest possible variety of likeminded people.

- Wherever possible, show your enemies kindness. Do them as much good you can. At least, sincerely wish them well.

- For the rest, entrust yourself and your enemies to the great Mystery of life that has assigned us such different – and often opposing – roles, and that will see us through if we play or part with love.