- Home

- Process Worldview

- Community

- Art and Music

- Whitehead and Process Thinking

- Podcasts

- Spirituality

- Ecological Civilization

- Education

- Contact

- Social Justice

- Science

- Animals

- Sacred Poems

- Whitehead Videos

- Index of All Titles

- Practicing Process Thought

- Process Spirituality: A Spiritual Alphabet

- Recent Posts

Jerusalem

|

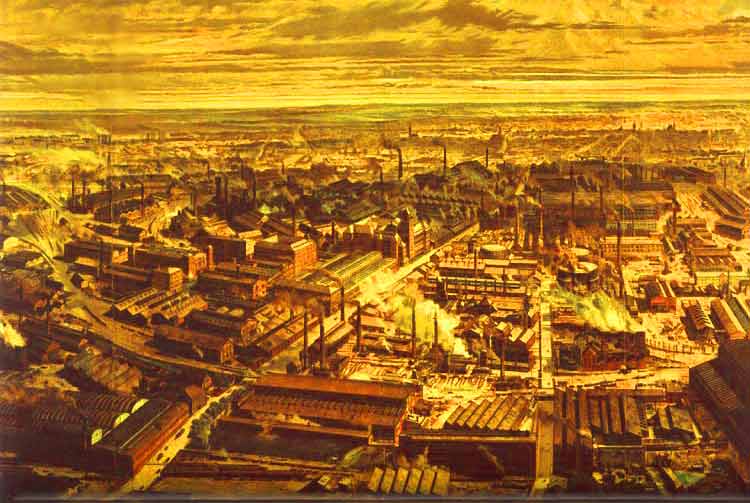

The video -- offered by BBC in its Let Poetry Into Your Life Series -- brings William Blake alive in a playful yet serious rendition of a football signing which stops London in its tracks. The poem, often called Jerusalem, is commonly interpreted as a critique of the industrial revolution and its "dark Satanic mills." The idea is that Jesus, prince of peace and minister of love, would do things differently. Christian theologian, John Cobb, agrees. He doesn't think Christians need to appeal to Jesus to respond constructively to our need for a different way of living. He thinks Christians can join others and appeal to the deeper hopes and better angels of humanity. These angels emerge out of a love of life itself. Here's how he sees things:

Toward a Humane, Sustainable

Post-Industrial Economy The most important revolution in history is the industrial one. Prior to it, there had been many important changes in the way of life of masses of people, but the capacity of people to produce goods and services in an agricultural economy had not varied greatly over time. In almost all societies the masses of people lived on the land at a subsistence level, while a few gained wealth by siphoning off what was more than needed for the subsistence of the farmers. This surplus supported life in towns and even cities, where a middle class of artisans, merchants, and professionals developed alongside an urban proletariat. A few lived in great luxury. In general, the limited availability of food for the poor played a primary role in preventing rapid population increase. What was discovered in the eighteenth century was that the same number of workers could produce a great deal more. The early focus was on the production of clothing and furniture and household goods and tools and machines. It turned out that by organizing workers in assembly lines and supporting them with energy from coal, production per hour of work could be vastly increased. There could be abundance of goods that had formerly been scarce and their price could be greatly reduced. What had formerly been luxuries for the rich could now be made available to the masses. From the beginning there was a price to pay. The satisfaction artisans felt in their work was denied to assembly-line workers. Factories brought with them pollution of a type not previously known. The aim at profit for the investors in a factory led to exploitation of labor that was in some ways more vicious than the exploitation of peasants in the countryside. Industrial cities were typically filled with slums. Unemployment became a problem rarely experienced in agricultural societies. The landed nobility saw that its power was passing into the hands of industrial capitalists. Noblesse oblige gave way to a single-minded quest for profit. Not everyone was pleased by the changes effected by industrialization, but there was little prospect of turning back the clock. Over time the industrial model was applied more and more widely. Eventually agriculture was also industrialized, and features of the industrial method were applied to merchandizing as well. Increasing productivity, defined as production per hour of labor became the norm everywhere. The industrial economy required larger markets. There were economies of scale; so that one huge factory could often under price several smaller ones. But to sell its product it needed more customers. This affected international relations as industrial powers sought markets all over the world. Factories often needed natural resources not plentiful locally. Hence nations whose policies were driven by economic concerns were also interested in securing supplies of such resources. There was another great advance of empire building. There was also a drive, especially after World War II to make of the whole globe a single market, so that goods could be produced wherever conditions were most favorable and sold wherever they were in demand. Modern economic theory beginning with Adam Smith grew up alongside industrialization. The economists explained the benefits of industrialization and sided with industrialists against those who wanted to curtail their freedom. They saw not only factory production but the whole of the economy as ideally geared to “growth” measured by total production of goods and services per capita. They were strong advocates of the move toward a global market. Mainstream economists have based their study and theories on industrial society. Today the financial sector has come to dominate the productive one. It clearly dominates government as well. Its control of the money supply is a major source of its power. Economists have far less understanding of this phenomenon than of the industrial economy it supersedes. Markets controlled by banks are not free. We might expect that economic theorists would be concerned with the ability of the environment to supply all the raw materials needed for a growing industry. However, they have largely dismissed this problem. They note that as a particular resource becomes scarce its price rises. This leads users to be more frugal and efficient with this resource and also to seek more plentiful, and therefore less expensive, substitutes. Such scarcity also leads inventors to find new ways of meeting the need that do not require the scarce item. Economists assure us that economic signals lead to developments that by-pass the problem of scarcity. They do not view resource scarcity as placing any limit on growth. Although there has been less discussion of pollution until very recently, economists try to subsume this under the same type of response. Those few who argue against unlimited growth of the human economy are viewed as outsiders to the community. The idea of “overshoot and collapse” comes from zoology and, as explained above, has no role in mainstream economic thinking. Today, the acute problem of global warming calls for the application of this concept to human affairs. But thus far it has been excluded from economic theory. Economists remain cheer leaders for economic growth everywhere and under almost any circumstances. They have been deeply misled by the modern worldview in its most harmful form. Fortunately, largely outside of academic departments and of the economics guild, others are developing an ecological economics that emphasizes the issue of scale. They note that the human economy is a subset of the natural economy and must remain a limited portion. As long as the natural economy is limited, the human economy must also be limited. Herman Daly has long been the leader in this development. Ecological economists redefine the goal of the economy. One important contribution to this task is the book, “The Economics of Happiness” by Mark Anielski. (New Society Publishers, 2007) We have found that the growth so prized by economists does not, in any regular way, make for the happiness of real people. To pursue growth when it does not contribute to the well being of people is quite mistaken. The task of economists is to find the ways of organizing the economy that contribute most to human well-being. The Kingdom of Bhutan now measures its wellbeing in terms of Gross National Happiness. A major shift that helps redefine the goal of economics is that from the individualism that underlies all mainstream economic theory to an appreciation for community. We now know that, beyond a very limited level, personal happiness is more a function of human relations than of the quantity of goods and services consumed. Unfortunately, modern thought has led economists astray. They have ignored human relations other than those of contract and exchange. Often the way of benefiting people is to improve the quality of the communities in which they live, but the application of modern economic thought has systematically destroyed communities. Focusing on community does not mean rejecting economic growth. Many communities are improved by increasing the supply of fresh water, food, improved shelter, education, and medical care. However, forcing people to leave their communities in order to find employment rarely adds to human well being. Even “economics for happiness” does not go far enough in our time. As Anielski and the rulers of Bhutan fully understand, human happiness cannot be separated from the flourishing of the whole ecosystem. We need an economic theory directed to the regeneration of the global biosphere. The move toward an ecological economy will require breaking the control of financial institutions over both industry and government. The key to this is recovering for community, at whatever level, the control over the money supply. Nationalizing the “Federal” Reserve system would transform the situation for the United States. State banks, like that in North Dakota, would greatly improve the financial condition of states. Money creation is possible at still smaller levels. The present global economy is collapsing. Rather than trying to stave off this collapse, we can use the occasion to build local economies that serve their communities well. This will be a profound reversal of long-term trends. It may include state and municipal banks and local currencies that free the community from subservience to the international banks. Local economies can encourage frugality and sustainability instead of growth. They need not look to growth to solve the problems of the poor. Instead, the local community will accept responsibility for providing work for all who want it and for meeting the essential needs also of those who cannot work. We may exchange the “high” standard of living measured by the surfeit of goods for a secure place in a healthy human community in a healthy ecological context. -- John Cobb in Ten Ideas for Saving the Planet |