Can Trees Make Us Happier?

Ecological Civilizations, Mental Health, the Cobb Eco-Village,

and The Greater Good Science Center at UC Berkeley

\

In light of global climate change, ethnic nationalisms, environmental destruction, violence at home and abroad, and gaps between haves and have nots, it's pretty clear. The best hope of the world -- and perhaps the only real hope -- is that we develop communities in rutal and urban settings that are creative, compassionate, participatory, diverse, inclusive, humane to animals, good for the earth, and spiritually satisfying, with no one left behind. These communities are the building blocks of what process philosophers and many others call ecological civilizations. We might also call them compassionate societies, recocnizing that compassion extends to the more-than-human world as well as human beings. Their citizens live with a recognition that all life is precious and that we are small but included in a larger web of mutual becoming that is the earth, our home.

Science

Toward the end of helping cultivate these communies we need science. Not only the science that helps us understand how the world works and the laws that inform it, but also science that helps us become whole people helping to create a whole world. Researchers in psychology, sociology, and neuroscience are already exploring these topics in great depth. They are exploring the dynamics and practices of awe, compassion, empathy, forgiveness. gratitude, happiness, social connections, mindfulness, empathy, and peace-making or bridge-building. With their insights they can assist in hope of building ecological civilizations or compassionate societies. The Greater Good Center at the University of California, Berkeley offers just this kind of assistance: "The Greater Good Science Center studies the psychology, sociology, and neuroscience of well-being and teaches skills that foster a thriving, resilient, and compassionate society."

Spirituality

Of course science is not enough. We also need spirituality. By spirituality I mean various forms of embodied wisdom and emotional intelligence that help us care for ourselves, one another, other animals, and the earth. We might call them "qualities of mind and heart" or "forms of relatedness." They include the various behaviors presented by the Greater Good Science Center, plus more. Here is a list developed by the world's most influential interfath spirituality network: Spirituality and Practice.

Attention -- Beauty -- Being Present -- Compassion -- Connections -- Devotion -- Enthusiasm -- Faith -- Forgiveness -- Grace -- Gratitude -- Hope -- Hospitality -- Imagination -- Joy -- Justice -- Kindness -- Listening -- Love -- Meaning -- Nurturing -- Openness -- Peace -- Play -- Questing -- Reverence -- Shadow -- Silence -- Teachers (learning from) -- Transformation -- Unity -- Vision -- Wonder -- X (the Mystery) -- Yearning -- You (self-compassion) -- Zeal (zest for life)

These qualities of heart and mind constitute a spiritual alphabet that can enrich individual lives at home and in the workplace, and also the overall cultural atmosphere of a compassionate society. The qualities are available to religious and non-religious alike. Religious people may understand them as ways of touching God, understood as a higher power or deeper source; non-religious people may understand them as ways of constructively participating in a universe that is a communion of subjects, not a collection of objects. Many will understand them both ways.

Social Media and Technology

Toward the end of creating ecological civilizations, it is not enough to focus on science and spirituality are not enough. Any realistic approach to helping build ecological civilizations will need to pay attention, and develop a responsible use of, social media and technology. Here again, the Greater Good Science Center offers the help we need. The staff at the center are not naive. They know that social media and technology can be, and are, misused, and that there are negative effects even in its constructive uses. However, they also know that social media and technology are here to stay, and they offer much wisdom on how to use media and technology responsibly, as in articles such as Five Ways to Build Caring Community on Social Media. The Greater Good Science Center has devoted an entire section of its work to exploring the negative and positive effects of social media and technology. See Media and Technology.

Who Cares?

There are people all over the world who are committed to the development of these communities and who can benefit from the insights offered by the Greater Good Center. These include the millennials involved in the Cobb Eco-Village (or Sunshine Eco-Village) just outside Hangzhoul, China. You see some of them in the photo above. Coming to a rural area in China from the city, and seeking to learn from traditional farmers, their aim is to reclaim the wisdom of agriculatural traditions practically and spiritually, in cooperation with the farmers who function as their mentors. Together with the farmers they are seeking to develop an eco-community that is strong, resilient, and vital. Their name comes from the fact that they are influenced and supported by the vision of John B. Cobb, Jr., a leading advocate of eco-philosophy in the West, and also by the work of the INsgitute for the Postmodern Development of China, directed by Zhihe Wang and Meijun Fan. They are quite sophisticated technologically, even as they are also learning how to plant, farm, and harvest crops for local markets. In one of the photos you see them using Zoom to have a seminar with John Cobb.

The remainder of this page offers resources for people interested in eco-civilizations as they might be enriched by insights from the Greater Good Science Center and, at the end, an essay by process novelist, Patricia Adams Farmer.

Science

Toward the end of helping cultivate these communies we need science. Not only the science that helps us understand how the world works and the laws that inform it, but also science that helps us become whole people helping to create a whole world. Researchers in psychology, sociology, and neuroscience are already exploring these topics in great depth. They are exploring the dynamics and practices of awe, compassion, empathy, forgiveness. gratitude, happiness, social connections, mindfulness, empathy, and peace-making or bridge-building. With their insights they can assist in hope of building ecological civilizations or compassionate societies. The Greater Good Center at the University of California, Berkeley offers just this kind of assistance: "The Greater Good Science Center studies the psychology, sociology, and neuroscience of well-being and teaches skills that foster a thriving, resilient, and compassionate society."

Spirituality

Of course science is not enough. We also need spirituality. By spirituality I mean various forms of embodied wisdom and emotional intelligence that help us care for ourselves, one another, other animals, and the earth. We might call them "qualities of mind and heart" or "forms of relatedness." They include the various behaviors presented by the Greater Good Science Center, plus more. Here is a list developed by the world's most influential interfath spirituality network: Spirituality and Practice.

Attention -- Beauty -- Being Present -- Compassion -- Connections -- Devotion -- Enthusiasm -- Faith -- Forgiveness -- Grace -- Gratitude -- Hope -- Hospitality -- Imagination -- Joy -- Justice -- Kindness -- Listening -- Love -- Meaning -- Nurturing -- Openness -- Peace -- Play -- Questing -- Reverence -- Shadow -- Silence -- Teachers (learning from) -- Transformation -- Unity -- Vision -- Wonder -- X (the Mystery) -- Yearning -- You (self-compassion) -- Zeal (zest for life)

These qualities of heart and mind constitute a spiritual alphabet that can enrich individual lives at home and in the workplace, and also the overall cultural atmosphere of a compassionate society. The qualities are available to religious and non-religious alike. Religious people may understand them as ways of touching God, understood as a higher power or deeper source; non-religious people may understand them as ways of constructively participating in a universe that is a communion of subjects, not a collection of objects. Many will understand them both ways.

Social Media and Technology

Toward the end of creating ecological civilizations, it is not enough to focus on science and spirituality are not enough. Any realistic approach to helping build ecological civilizations will need to pay attention, and develop a responsible use of, social media and technology. Here again, the Greater Good Science Center offers the help we need. The staff at the center are not naive. They know that social media and technology can be, and are, misused, and that there are negative effects even in its constructive uses. However, they also know that social media and technology are here to stay, and they offer much wisdom on how to use media and technology responsibly, as in articles such as Five Ways to Build Caring Community on Social Media. The Greater Good Science Center has devoted an entire section of its work to exploring the negative and positive effects of social media and technology. See Media and Technology.

Who Cares?

There are people all over the world who are committed to the development of these communities and who can benefit from the insights offered by the Greater Good Center. These include the millennials involved in the Cobb Eco-Village (or Sunshine Eco-Village) just outside Hangzhoul, China. You see some of them in the photo above. Coming to a rural area in China from the city, and seeking to learn from traditional farmers, their aim is to reclaim the wisdom of agriculatural traditions practically and spiritually, in cooperation with the farmers who function as their mentors. Together with the farmers they are seeking to develop an eco-community that is strong, resilient, and vital. Their name comes from the fact that they are influenced and supported by the vision of John B. Cobb, Jr., a leading advocate of eco-philosophy in the West, and also by the work of the INsgitute for the Postmodern Development of China, directed by Zhihe Wang and Meijun Fan. They are quite sophisticated technologically, even as they are also learning how to plant, farm, and harvest crops for local markets. In one of the photos you see them using Zoom to have a seminar with John Cobb.

The remainder of this page offers resources for people interested in eco-civilizations as they might be enriched by insights from the Greater Good Science Center and, at the end, an essay by process novelist, Patricia Adams Farmer.

Practices for Daily Life Recommended and Developed

by the Greater Good Science Center at Berkeley

The Greater Good Science Center

"The Greater Good Science Center studies the psychology, sociology, and neuroscience of well-being and teaches skills that foster a thriving, resilient, and compassionate society." "Our free online magazine, Greater Good, turns scientific research into stories, tips, and tools for a happier life and a more compassionate society. Its mission is to bridge the gap between scientific journals and people’s daily lives, applying cutting-edge research to homes and workplaces, particularly for parents, educators, business leaders, and health care professionals." "Based at UC Berkeley, Greater Good reports on groundbreaking research into the roots of compassion, happiness, and altruism. The results are impressive and eminently available to the general public through their magazine"-- Greater Good: Science-Based Insights or a Meaningful Life. |

Why Trees Can Make Us Happier

click on button for article:

|

Why is Nature so Good for Mental Health?

click on button for article:

|

In an ecological civilization spirituality is a combination of emotional intelligence and embodied wisdom in daily life. It can be, but need not be, associated with religion or belief in a higher power. What, then, are the spiritual emotions available to human beings and how might we practice them?

The best answer to this question today comes from a worldwide resource for spiritual development called Spirituality and Faith. It offers a list of 37 qualities of heart and mind, forms of relatedness, that constitute the spiritual vocabulary of human beings. Many of them overlap with the Ten Key Behaviors offered by the Greater Good Science Center, but they include more qualities of heart and mind on which, in principle, science-based research can be done in a field we might call Positive Spirituality. See What is the Role of Spirituality in an Ecological Civilization? The thirty seven are:

The best answer to this question today comes from a worldwide resource for spiritual development called Spirituality and Faith. It offers a list of 37 qualities of heart and mind, forms of relatedness, that constitute the spiritual vocabulary of human beings. Many of them overlap with the Ten Key Behaviors offered by the Greater Good Science Center, but they include more qualities of heart and mind on which, in principle, science-based research can be done in a field we might call Positive Spirituality. See What is the Role of Spirituality in an Ecological Civilization? The thirty seven are:

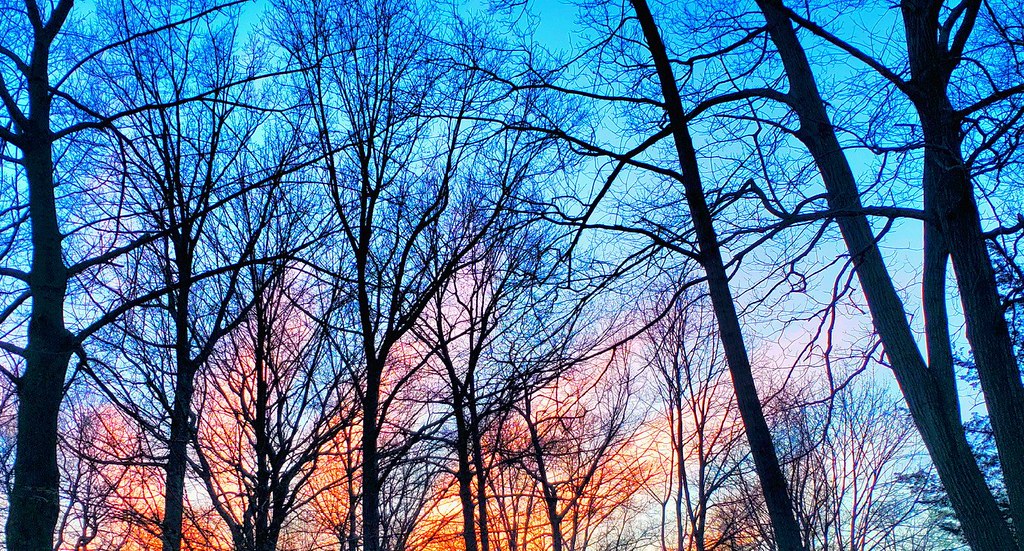

"On the Gratitude of Trees" by Patricia Adams Farmer

TREES ARE EVERYTHING I long to be: deep, tall, gorgeous, hospitable, and unapologetically assertive as they stretch upward in hungry yearning for the sky. Trees are like souls, fat souls, lively souls, and like us, they change. They just can’t stay the same. No one ever wrote in the school year book of a tree “Never change,” for that would be the silliest idea for a tree (and for people, too). For trees are all about change and growth and loss and rebirth. But they don’t mind—they really don’t. In fact, trees are monuments to gratitude and worthy of recognition at Thanksgiving. That’s because trees are wise and grateful even in late autumn when their leaves fall off, yes, even while they are shivering and naked and vulnerable and quite lacking in leafy frills and fruit. They may prefer to be green or vermilion or yellow-gold or studded with ripe, red berries--who wouldn't?--but still, they appreciate what the emptiness reveals.

At Thanksgiving we tend to list the things that are already realized in our life, like family and friends, food and shelter, things and loves that we possess in one way or another. It is good to be thankful for what we have. But if take a walk in the park in autumn, we find that trees ask us to stretch our souls a bit further by adding to the list a few things that we do not possess, but that perhaps possess us: like change itself, the moments of becoming and freshness, the seasons of life, the possibilities, the surprises.

Sometimes gratitude in any form feels like a stretch, especially when we are losing leaves by the barrel full. We may have lost a love, a hope, a dream; perhaps we are old and losing our hearing or our eyesight; youth itself may have come and gone before we knew what was happening. We may have even lost faith in people, in peace, in justice, like leaves devoid of nutrients, turning and torn. Discontent sets in. Trees know all about that wintry discontent, that quiet patience—faith, if you will—that spring will come. Patience born on faith: this quiet, invisible blessing, must be counted too, says the tree.

Trees teach us about widening out, stretching our souls toward the sky of possibility, toward God, toward love. They teach us about being aware of more than our little patch of earth, a mindfulness which promulgates a wider sense of gratitude. The Chinese Pistache is a case in point. Of all the trees in the park in autumn, nothing can touch the Chinese Pistache when it comes to color—a show-stopping rubicund of tree perfection, its radiance catching fire in the attenuated sun. The Chinese Pastiche is a god in the community of trees, at least for a month or two. These delicate, perfectly shaped trees sporting the most delicious shades of red, tend to feel a bit smug around early November; but by the end of the month, they find themselves invisible, sticks in the wind, spiny and colorless, bowing humbly before the giant, husky cottonwood, which knows how to keep its luscious leaves of shimmering gold intact a bit longer. And then there is that annoying Evergreen, which never seems to change at all. If the Chinese Pistache can ever get over its envy, it can become a Zen master, and learn to look outside oneself to the beauty of the whole.

The community of trees in a park reminds us that if we want to become larger souls—buoyant, resilient, gorgeously fat souls—we might consider giving thanks for wider things than what we have now, for the ability to get over ourselves and our grasping after things, yes, to be grateful even for change itself. For change means possibility, and possibility means hope.

Sometimes our leafy branches blind us to this a wider world of beauty, diversity, interconnection, and deep belonging. During winter, we have a clearer vision. In our wider, unobstructed view of things, we can learn to be grateful for the beauty beyond our own state of affairs. We can grateful that we are not alone in this unpredictable and scary world, but part of a community of fellow-trees rooted in the earth on a planet chock- full of beauty-in-motion. We can be thankful for futures not yet written, for buds not yet formed, for fruit tasted only in the imagination, for the sheer possibilities within our wintry branches.

We can become like trees, Zen masters of gratitude during every season. Just take a walk in the park after the Thanksgiving feast and all will be made clear.

At Thanksgiving we tend to list the things that are already realized in our life, like family and friends, food and shelter, things and loves that we possess in one way or another. It is good to be thankful for what we have. But if take a walk in the park in autumn, we find that trees ask us to stretch our souls a bit further by adding to the list a few things that we do not possess, but that perhaps possess us: like change itself, the moments of becoming and freshness, the seasons of life, the possibilities, the surprises.

Sometimes gratitude in any form feels like a stretch, especially when we are losing leaves by the barrel full. We may have lost a love, a hope, a dream; perhaps we are old and losing our hearing or our eyesight; youth itself may have come and gone before we knew what was happening. We may have even lost faith in people, in peace, in justice, like leaves devoid of nutrients, turning and torn. Discontent sets in. Trees know all about that wintry discontent, that quiet patience—faith, if you will—that spring will come. Patience born on faith: this quiet, invisible blessing, must be counted too, says the tree.

Trees teach us about widening out, stretching our souls toward the sky of possibility, toward God, toward love. They teach us about being aware of more than our little patch of earth, a mindfulness which promulgates a wider sense of gratitude. The Chinese Pistache is a case in point. Of all the trees in the park in autumn, nothing can touch the Chinese Pistache when it comes to color—a show-stopping rubicund of tree perfection, its radiance catching fire in the attenuated sun. The Chinese Pastiche is a god in the community of trees, at least for a month or two. These delicate, perfectly shaped trees sporting the most delicious shades of red, tend to feel a bit smug around early November; but by the end of the month, they find themselves invisible, sticks in the wind, spiny and colorless, bowing humbly before the giant, husky cottonwood, which knows how to keep its luscious leaves of shimmering gold intact a bit longer. And then there is that annoying Evergreen, which never seems to change at all. If the Chinese Pistache can ever get over its envy, it can become a Zen master, and learn to look outside oneself to the beauty of the whole.

The community of trees in a park reminds us that if we want to become larger souls—buoyant, resilient, gorgeously fat souls—we might consider giving thanks for wider things than what we have now, for the ability to get over ourselves and our grasping after things, yes, to be grateful even for change itself. For change means possibility, and possibility means hope.

Sometimes our leafy branches blind us to this a wider world of beauty, diversity, interconnection, and deep belonging. During winter, we have a clearer vision. In our wider, unobstructed view of things, we can learn to be grateful for the beauty beyond our own state of affairs. We can grateful that we are not alone in this unpredictable and scary world, but part of a community of fellow-trees rooted in the earth on a planet chock- full of beauty-in-motion. We can be thankful for futures not yet written, for buds not yet formed, for fruit tasted only in the imagination, for the sheer possibilities within our wintry branches.

We can become like trees, Zen masters of gratitude during every season. Just take a walk in the park after the Thanksgiving feast and all will be made clear.