- Home

- Process Worldview

- Community

- Art and Music

- Whitehead and Process Thinking

- Podcasts

- Spirituality

- Ecological Civilization

- Education

- Contact

- Social Justice

- Science

- Animals

- Sacred Poems

- Whitehead Videos

- Index of All Titles

- Practicing Process Thought

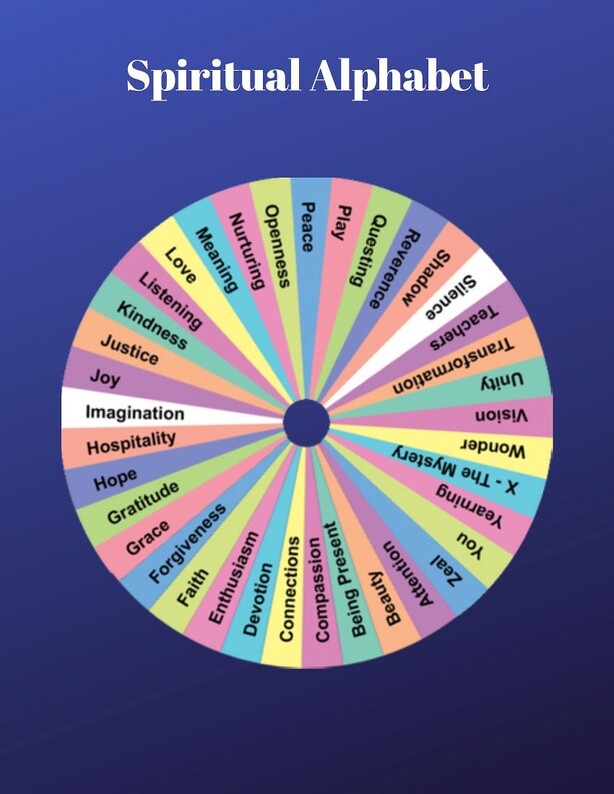

- Process Spirituality: A Spiritual Alphabet

- Recent Posts

China's Spiritual Awakening

and the small role that process philosophy is playing in it

A spiritual awakening is occuring in China today that is supported by the government but also transcends the government. Process philosophy is playing small but important role in this awakening by introducing the idea that a person can partake of, and enjoy, spiritual well-being independently of formal religious affiliation.

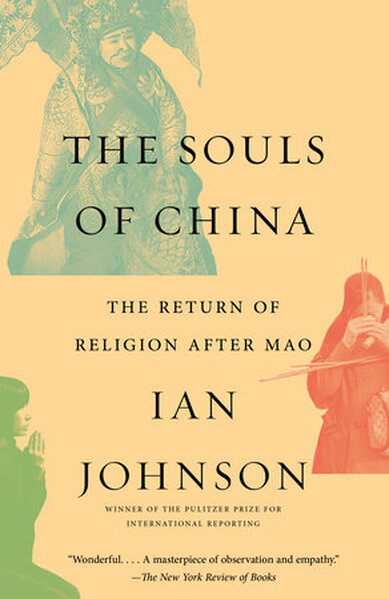

The awakening itself, quite apart from the influence of process philosophy, is described by Ian Johnson in his award-winning book The Souls of China: The Return of Religion After Mao. He also describes it in an essay in the NY Times.

The awakening itself, quite apart from the influence of process philosophy, is described by Ian Johnson in his award-winning book The Souls of China: The Return of Religion After Mao. He also describes it in an essay in the NY Times.

As Johnson makes clear, the awakening is not formally religious in ways that Westerners might recognize. It is not a promotion of Christianity or Islam. Indeed, the government is suppressing both of these traditions. Johnson puts it this way:

"Officials believe these two global faiths are hard to control because of their foreign ties, and they have used negotiation or force — diplomacy with the Vatican, arrests of prominent Protestants, internment camps for Muslims — to try to bring these religions to heel....Yet Beijing’s recent turn to tradition may be even more significant. Even though Islam and Christianity are world religions, in China they remain minor, with the number of their combined adherents amounting to less than 10 percent of the population. Most Chinese believe in an amalgam of Buddhism, Taoism, Confucianism and other traditional values and ideas that still resonate deeply. (Ian Johnson NY Times Essay)

The upshot is that the spiritual awakeng supported by the government builds upon indigenous Chinese traditions (folk, Confucian, Daoist, and Chinese Buddhist).

The government is supporting and encouraging this awakening, because it knows that Chinese need a moral and spiritual compass that is not offered by Chinese Communism. Chinese Communism will be the economic and political foundation for China's future. But the Chinese yearn for something more, and the government knows it. Something like "faith" or "spirituality" can help. The Chinese governments plan is to encourage a revival of tradition:

"The plan stems from a widespread feeling that China’s relentless drive to get ahead economically has created a spiritual vacuum, and sometimes justifies breaking rules and trampling civility. Many people do not trust one another. The government’s blueprint for handling this moral crisis calls for endorsing certain traditional beliefs." (Ian Johnson, NY Times)

Enter process philosophy. It is not a traditional Chinese belief, but its general ideas support many such beliefs. In many ways it feels Chinese to many Chinese, albeit with the added component of science, which appeals to Chinese as well. (For more on the connections, see Process Philosophy and Chinese Philosophy.)

Accordingly, process philosophy is now playing a small but important role in the current spiritual awakening, largely through the efforts of Zhihe Wang and Meijun Fan of the Institute for the Postmodern Development of China. Through their work in their homeland, many of the ideas essential to process philosophy are being studied, explored, and applied in various Chinese contexts: rural development, urban development, culture studies, psychology, economics, cosmology, and education.

To be sure, the formal mission of IPDC is not to promote religion or spirituality. The mission statement of IPDC is as follows: "The Institute for the Postmodern Development of China weds the best Chinese and Western resources to identify global pathways toward ecological civilization."

"Officials believe these two global faiths are hard to control because of their foreign ties, and they have used negotiation or force — diplomacy with the Vatican, arrests of prominent Protestants, internment camps for Muslims — to try to bring these religions to heel....Yet Beijing’s recent turn to tradition may be even more significant. Even though Islam and Christianity are world religions, in China they remain minor, with the number of their combined adherents amounting to less than 10 percent of the population. Most Chinese believe in an amalgam of Buddhism, Taoism, Confucianism and other traditional values and ideas that still resonate deeply. (Ian Johnson NY Times Essay)

The upshot is that the spiritual awakeng supported by the government builds upon indigenous Chinese traditions (folk, Confucian, Daoist, and Chinese Buddhist).

The government is supporting and encouraging this awakening, because it knows that Chinese need a moral and spiritual compass that is not offered by Chinese Communism. Chinese Communism will be the economic and political foundation for China's future. But the Chinese yearn for something more, and the government knows it. Something like "faith" or "spirituality" can help. The Chinese governments plan is to encourage a revival of tradition:

"The plan stems from a widespread feeling that China’s relentless drive to get ahead economically has created a spiritual vacuum, and sometimes justifies breaking rules and trampling civility. Many people do not trust one another. The government’s blueprint for handling this moral crisis calls for endorsing certain traditional beliefs." (Ian Johnson, NY Times)

Enter process philosophy. It is not a traditional Chinese belief, but its general ideas support many such beliefs. In many ways it feels Chinese to many Chinese, albeit with the added component of science, which appeals to Chinese as well. (For more on the connections, see Process Philosophy and Chinese Philosophy.)

Accordingly, process philosophy is now playing a small but important role in the current spiritual awakening, largely through the efforts of Zhihe Wang and Meijun Fan of the Institute for the Postmodern Development of China. Through their work in their homeland, many of the ideas essential to process philosophy are being studied, explored, and applied in various Chinese contexts: rural development, urban development, culture studies, psychology, economics, cosmology, and education.

To be sure, the formal mission of IPDC is not to promote religion or spirituality. The mission statement of IPDC is as follows: "The Institute for the Postmodern Development of China weds the best Chinese and Western resources to identify global pathways toward ecological civilization."

But in the context of working toward such a civilization, Wang and Fan, along with many other working with IPDC, are helping many Chinese, young and old, claim a spiritual side to their lives.

The Two Fronts

All of this is to day that process philosophy is especially relevant to Chinese on two fronts. On the one hand it offers a philosophy conducive to the cultivation of a social ideal: the building of an Ecological Civilization in which people live with respect and care for one another and the larger community of life. Many Chinese know that they they need to evolve into an Ecological Civilization, even as they are quite distant from being such a civilization today. Process philosophy provides a foundation for that evolution. See, for example, the work of IPDC with it many conferences, in China and the US, on this subject.

On the other hand, with its appreciation of the role that emotion and feeling plays in human life, process philosophy offers an outlook on life conducive to the cultivation of personal spirituality and satisfying personal relationships at home, in the workplace, and in the larger community. It offers a "spirituality" that can be adopted to many different circumstances and embraced from many different points of view, including Buddhist and Confucian and Daoist as well as Christian and Muslim and Jewish. The kind of "spirituality" recommended by process philosophy can likewise be embraced by the many Chinese who are formally atheistic or "spiritual but not religious."

Of course 'spirituality' is a loaded and contested word. In the context of my own work in China, I define it as positive psychology and embodied wisdom in daily life. It can be studied scientifically and explored artistically, as well as appreciated philosophically and, most important, practiced in daily life. For my part, I find the spiritual alphabet of one of the world's most influential interfaith organizations, Spirituality and Practice. most helpful for understanding the wide range of emotions or subjective forms that make sense philosophically (from a process perspective) and that are relevant to Chinese today. I tell that story next.

-- Jay McDaniel

The Two Fronts

All of this is to day that process philosophy is especially relevant to Chinese on two fronts. On the one hand it offers a philosophy conducive to the cultivation of a social ideal: the building of an Ecological Civilization in which people live with respect and care for one another and the larger community of life. Many Chinese know that they they need to evolve into an Ecological Civilization, even as they are quite distant from being such a civilization today. Process philosophy provides a foundation for that evolution. See, for example, the work of IPDC with it many conferences, in China and the US, on this subject.

On the other hand, with its appreciation of the role that emotion and feeling plays in human life, process philosophy offers an outlook on life conducive to the cultivation of personal spirituality and satisfying personal relationships at home, in the workplace, and in the larger community. It offers a "spirituality" that can be adopted to many different circumstances and embraced from many different points of view, including Buddhist and Confucian and Daoist as well as Christian and Muslim and Jewish. The kind of "spirituality" recommended by process philosophy can likewise be embraced by the many Chinese who are formally atheistic or "spiritual but not religious."

Of course 'spirituality' is a loaded and contested word. In the context of my own work in China, I define it as positive psychology and embodied wisdom in daily life. It can be studied scientifically and explored artistically, as well as appreciated philosophically and, most important, practiced in daily life. For my part, I find the spiritual alphabet of one of the world's most influential interfaith organizations, Spirituality and Practice. most helpful for understanding the wide range of emotions or subjective forms that make sense philosophically (from a process perspective) and that are relevant to Chinese today. I tell that story next.

-- Jay McDaniel

The Spiritual Alphabet

also posted Spirituality and Practice

I have spent a lot of time in mainland China over the years, teaching process philosophy to students young and old. The youngest are in kindergarten and the oldest are in their late eighties. I’ve been fifteen times in thirteen years.

One thing I’ve discovered in China is that philosophy cannot and need not be separated from everyday life and emotions. A philosophy quickly becomes irrelevant if it seems to be only a matter of the head not the heart, and if it lacks relevance to interactions with friends, family, and neighbors.

Thus I have appreciated aspects of process philosophy that are too often ignored by Western audiences: namely its emphasis on what Whitehead called subjective forms.

When we hear the word “form” we may initially think of objective forms: that is, the shapes and patterns of things we see in our eyes and entertain in our minds. The shapes of tables and chairs and trees and stars, for example. Subjective forms are different. They are the emotions we experience as we see with our eyes and entertain ideas in our minds. They are subjective, not objective. Awe, wonder, curiosity, fear, anxiety: these are subjective forms.

Chinese friends are especially interested in positive subjective forms: the emotions that can be part of a healthy life. Some speak of a life nurtured by positive subjective forms as spirituality. Of course the nurturing is itself an ongoing process, animated and guided by friends and family, hills and rivers, music and poems. “N” is for nurturing.

Knowing my context. I share the spiritual alphabet of Spirituality and Practice, using the diagram above. I introduce the letters in the alphabet as qualities of heart and mind and forms of relatedness that can help a person find a bit of happiness, given the circumstances of life. As I do so, I do not speak of “God” or “religion.” These words can evoke problematic feelings in some Chinese who have been conditioned to be resistant to both words. For many of them, rightly or wrongly, religion is too often superstitious and divisive; and God is an emperor in the sky, rightly rejected in the interests of freedom and human development.

Those of us who use the alphabet know that it is tremendously powerful as a way of naming and thus becoming mindful of some of the most important things in life: love and wonder, kindness and play, listening and beauty, for example.

And we also know that it can function as an invitation to imagine additional positive subjective forms that may not be obviously present in the alphabet. In China one important example of this is the letter C. In the alphabet it has two meanings: compassion and connection. Of course these are very important to all people, including Chinese. One reason people in China are drawn to process philosophy is that they believe it can encourage and support a deeply compassionate way of living in the world.

But one time, in exploring the letter C, a twenty-year old student said: “But what about curiosity. Can’t C stand for curiosity, too? For me this is one of the most important spiritual qualities available to us.” His English name was Michael, and his specialty was physics. As Michael said this, I thought of the letter Q. “Q’ is for questing, and the pleasures of curiosity are indeed a form of questing. But I didn’t seem right in the moment to say to my friend “curiosity is a form of questing,” as if his insight gained validity only when subsumed in an already existing template. It seemed best to say: “You’re right! Add it!” I’m sure he did along with others in the group.

My own process musing these days, also a process hope, is that the spiritual alphabet can find its way into the hearts and minds of billions of Chinese who aren’t sure what they think about “religion” and “God” but sure know that they need and want wonder, imagination, love, listening, justice, and, yes, curiosity. And it is that the alphabet can find its heart in Americans and others, too. Any approximation of an Ecological Civilization depends on this. "H" is for hope.

-- Jay McDaniel

I have spent a lot of time in mainland China over the years, teaching process philosophy to students young and old. The youngest are in kindergarten and the oldest are in their late eighties. I’ve been fifteen times in thirteen years.

One thing I’ve discovered in China is that philosophy cannot and need not be separated from everyday life and emotions. A philosophy quickly becomes irrelevant if it seems to be only a matter of the head not the heart, and if it lacks relevance to interactions with friends, family, and neighbors.

Thus I have appreciated aspects of process philosophy that are too often ignored by Western audiences: namely its emphasis on what Whitehead called subjective forms.

When we hear the word “form” we may initially think of objective forms: that is, the shapes and patterns of things we see in our eyes and entertain in our minds. The shapes of tables and chairs and trees and stars, for example. Subjective forms are different. They are the emotions we experience as we see with our eyes and entertain ideas in our minds. They are subjective, not objective. Awe, wonder, curiosity, fear, anxiety: these are subjective forms.

Chinese friends are especially interested in positive subjective forms: the emotions that can be part of a healthy life. Some speak of a life nurtured by positive subjective forms as spirituality. Of course the nurturing is itself an ongoing process, animated and guided by friends and family, hills and rivers, music and poems. “N” is for nurturing.

Knowing my context. I share the spiritual alphabet of Spirituality and Practice, using the diagram above. I introduce the letters in the alphabet as qualities of heart and mind and forms of relatedness that can help a person find a bit of happiness, given the circumstances of life. As I do so, I do not speak of “God” or “religion.” These words can evoke problematic feelings in some Chinese who have been conditioned to be resistant to both words. For many of them, rightly or wrongly, religion is too often superstitious and divisive; and God is an emperor in the sky, rightly rejected in the interests of freedom and human development.

Those of us who use the alphabet know that it is tremendously powerful as a way of naming and thus becoming mindful of some of the most important things in life: love and wonder, kindness and play, listening and beauty, for example.

And we also know that it can function as an invitation to imagine additional positive subjective forms that may not be obviously present in the alphabet. In China one important example of this is the letter C. In the alphabet it has two meanings: compassion and connection. Of course these are very important to all people, including Chinese. One reason people in China are drawn to process philosophy is that they believe it can encourage and support a deeply compassionate way of living in the world.

But one time, in exploring the letter C, a twenty-year old student said: “But what about curiosity. Can’t C stand for curiosity, too? For me this is one of the most important spiritual qualities available to us.” His English name was Michael, and his specialty was physics. As Michael said this, I thought of the letter Q. “Q’ is for questing, and the pleasures of curiosity are indeed a form of questing. But I didn’t seem right in the moment to say to my friend “curiosity is a form of questing,” as if his insight gained validity only when subsumed in an already existing template. It seemed best to say: “You’re right! Add it!” I’m sure he did along with others in the group.

My own process musing these days, also a process hope, is that the spiritual alphabet can find its way into the hearts and minds of billions of Chinese who aren’t sure what they think about “religion” and “God” but sure know that they need and want wonder, imagination, love, listening, justice, and, yes, curiosity. And it is that the alphabet can find its heart in Americans and others, too. Any approximation of an Ecological Civilization depends on this. "H" is for hope.

-- Jay McDaniel

Want to know more about Process Philosophy

and the work of IPDC in China?

Here are some links.

The Return of Religion after Mao

ABOUT THE SOULS OF CHINA |