- Home

- Process Worldview

- Community

- Art and Music

- Whitehead and Process Thinking

- Podcasts

- Spirituality

- Ecological Civilization

- Education

- Contact

- Social Justice

- Science

- Animals

- Sacred Poems

- Whitehead Videos

- Index of All Titles

- Practicing Process Thought

- Process Spirituality: A Spiritual Alphabet

- Recent Posts

Crazy Horse

by John Trudell

After the Quaking and Breaking

(The Need to Widen Our Vision)

So the question, then, after the quaking and breaking subsides, is this: can we ever find solid ground again—a sense of reassurance that something is solid somewhere? The bleached, smooth corpses of trees, even in their stark demise, seem to answer in the affirmative. Of course time, nature's natural remedy, comes into play. Eventually the sand will cover up the dead timber, or it will be caught by a tide in the full moon and be swept away to other shores. People will come and carry it off to build houses and fences. The shore will, with time, be cleared. But time does not always clear away the debris of pain and heartbreak, not all by itself.

After sitting for awhile among the dead trees, I stood and stretched and looked up at the pillowy clouds and back to the mist-covered mountains in the distance, and then toward the wide sea. A flock of pelicans flew overhead, on a mission to somewhere. And it occurred to me, that one way through the quaking and breaking moments of life is to widen our vision.

For it is only natural that when even a single tree is torn from its roots,we feel as though everything is lost; that this single brutality drowns out all other signs of life. Our eyes lock themselves firmly on the pain and injustice and waste of this beautiful tree, so that we soon identify with the pain, until finally, we are the pain.

But we can stretch out our awareness a bit—slowly at first—until, one day, something within us suddenly breaks loose and we can see it: the whole, wide spacious sky. It is still there! We turn around to see verdant hills and mountains made of solid rock. They are still standing! We look toward the endless gray-blue sea still pounding out its ancient rhythm onto a welcoming shore. It is all still there!

-- Patricia Adams Farmer

After sitting for awhile among the dead trees, I stood and stretched and looked up at the pillowy clouds and back to the mist-covered mountains in the distance, and then toward the wide sea. A flock of pelicans flew overhead, on a mission to somewhere. And it occurred to me, that one way through the quaking and breaking moments of life is to widen our vision.

For it is only natural that when even a single tree is torn from its roots,we feel as though everything is lost; that this single brutality drowns out all other signs of life. Our eyes lock themselves firmly on the pain and injustice and waste of this beautiful tree, so that we soon identify with the pain, until finally, we are the pain.

But we can stretch out our awareness a bit—slowly at first—until, one day, something within us suddenly breaks loose and we can see it: the whole, wide spacious sky. It is still there! We turn around to see verdant hills and mountains made of solid rock. They are still standing! We look toward the endless gray-blue sea still pounding out its ancient rhythm onto a welcoming shore. It is all still there!

-- Patricia Adams Farmer

The Need to be Crazier than Hell

Imagine a group of people who are making hell on earth today. They are obsessed with oil and power, and with the movement of arms and money. They think numbers and data are more important than stories and songs, and they believe that the earth was created for human use. They don't know that rocks are alive and that the ancestral spirits are as real in their way as are the plants and animals around us. They think that the well-being of a society is measured in terms of gross domestic product rather than the well-being of life, both human and more-than-human. Intoxicated by ideologies of consumerism, they are blind to the beauty of the planet and the poignancy of each life. They are crazy as hell.

It will take somebody crazier than hell to see beyond their craziness. Someone who knows that the truly real things of our universe -- plants and animals, stars and planets, people and spirits -- are made of stories and songs rather than zeros and ones. Someone who knows that our calling in life is not to amass wealth beyond our need, but to hear the songs of creation and sing with all our relatives: friends and strangers, plants and animals, stars and planets. Someone who knows that we are bones made of spirit.

A Whiteheadian Appreciation of Shamanism

Yes, it will take someone like the philosopher Alfred North Whitehead, who offers ten ideas conducive to a philosophy of shamanism. Whitehead knows (1) that the entire universe is an ongoing journey which forever dances forward into an undetermined future from out of infinite memories of the past; (2) that so-called dead matter is filled with creative energy, which means that even rocks are alive in their way, radiant with a kind of personality; (3) that three-dimensional space is but one of an uncountable number of dimensions in which actualities can exist, suggesting that humans can access multiple planes of existence through multiple forms of feeling, some of which are in touch with eternal realities; (4) that each moment of experience -- whether human or angelic, atomic or divine -- is a coming together, a concrescence, of the whole past history of the universe, meaning that each bone in our body is a site where the many become one; (5) that human experience is always embodied, and that bodies can be invisible as well as visible; (6) that all beings are present in all other beings, which means that the universe is a seamless web of inter-dependence and mutual story-telling, incapable of being torn apart into absolutely separate compartments; (7) that all living beings tell stories, not only in how they present themselves to the world but in who they are from the inside, which means that stories are not mere appendages to what it means to be real, but the very essence of reality; (8) that human consciousness is but the tip of the experiential iceberg, which means that there are modes of knowing and feeling which far transcend verbal-linguistic knowing, and which can yield insights conducive to the well-being of life; (9) that science and art and religion are three ways of approaching the same reality, namely life itself; and (10) that the universe unfolds within the womb of a Creator spirit whose very breath can offer guidance for the journey of each soul, human and more-than-human.

And it will take someone who can articulate these sensibilities artistically, through music and image and movement, like the crazier than hell John Trudell, who reminds us that we can become fully human only as we remember the voices that rise up from within us, from out of a living universe in which bone and spirit are interwoven, helping us respond to the Creator spirit and find our calling as children of earth and sky.

Or someone who, like Patricia Adams Farmer, the Whitehead-influenced novelist who has authored the Fat Soul Philosophy series, invites us to take note of the way in which the warm energy of a rock is very sure of itself; and how ceibo trees are shamans in their own right, provoking and cajoling us into flights of imagination and self-awareness; and how even in the quaking and breaking of everything, the very endurance of rocks and bones invite us, as children of the earth, to recognize that we are also children of the sky.

Fat Soul Shamanism

For Patricia Adams Farmer a truly "fat" soul is not overweight, rather it is rightly and expansively sized. It is fat because it is wide enough to include the energy of rocks, the teaching of the ceibo, the quaking of the earth, and the multiplicity of the spirits, some of whom are in heaven and some on earth. A fat soul is a shamanic soul, crazier than hell and thus offering a portal by which the will of the heavenly Shaman might be done on earth as it is in heaven. Her words capture the spirit. Call it Fat Soul Shamanism.

- Jay McDaniel

It will take somebody crazier than hell to see beyond their craziness. Someone who knows that the truly real things of our universe -- plants and animals, stars and planets, people and spirits -- are made of stories and songs rather than zeros and ones. Someone who knows that our calling in life is not to amass wealth beyond our need, but to hear the songs of creation and sing with all our relatives: friends and strangers, plants and animals, stars and planets. Someone who knows that we are bones made of spirit.

A Whiteheadian Appreciation of Shamanism

Yes, it will take someone like the philosopher Alfred North Whitehead, who offers ten ideas conducive to a philosophy of shamanism. Whitehead knows (1) that the entire universe is an ongoing journey which forever dances forward into an undetermined future from out of infinite memories of the past; (2) that so-called dead matter is filled with creative energy, which means that even rocks are alive in their way, radiant with a kind of personality; (3) that three-dimensional space is but one of an uncountable number of dimensions in which actualities can exist, suggesting that humans can access multiple planes of existence through multiple forms of feeling, some of which are in touch with eternal realities; (4) that each moment of experience -- whether human or angelic, atomic or divine -- is a coming together, a concrescence, of the whole past history of the universe, meaning that each bone in our body is a site where the many become one; (5) that human experience is always embodied, and that bodies can be invisible as well as visible; (6) that all beings are present in all other beings, which means that the universe is a seamless web of inter-dependence and mutual story-telling, incapable of being torn apart into absolutely separate compartments; (7) that all living beings tell stories, not only in how they present themselves to the world but in who they are from the inside, which means that stories are not mere appendages to what it means to be real, but the very essence of reality; (8) that human consciousness is but the tip of the experiential iceberg, which means that there are modes of knowing and feeling which far transcend verbal-linguistic knowing, and which can yield insights conducive to the well-being of life; (9) that science and art and religion are three ways of approaching the same reality, namely life itself; and (10) that the universe unfolds within the womb of a Creator spirit whose very breath can offer guidance for the journey of each soul, human and more-than-human.

And it will take someone who can articulate these sensibilities artistically, through music and image and movement, like the crazier than hell John Trudell, who reminds us that we can become fully human only as we remember the voices that rise up from within us, from out of a living universe in which bone and spirit are interwoven, helping us respond to the Creator spirit and find our calling as children of earth and sky.

Or someone who, like Patricia Adams Farmer, the Whitehead-influenced novelist who has authored the Fat Soul Philosophy series, invites us to take note of the way in which the warm energy of a rock is very sure of itself; and how ceibo trees are shamans in their own right, provoking and cajoling us into flights of imagination and self-awareness; and how even in the quaking and breaking of everything, the very endurance of rocks and bones invite us, as children of the earth, to recognize that we are also children of the sky.

Fat Soul Shamanism

For Patricia Adams Farmer a truly "fat" soul is not overweight, rather it is rightly and expansively sized. It is fat because it is wide enough to include the energy of rocks, the teaching of the ceibo, the quaking of the earth, and the multiplicity of the spirits, some of whom are in heaven and some on earth. A fat soul is a shamanic soul, crazier than hell and thus offering a portal by which the will of the heavenly Shaman might be done on earth as it is in heaven. Her words capture the spirit. Call it Fat Soul Shamanism.

- Jay McDaniel

The Liberated Imagination

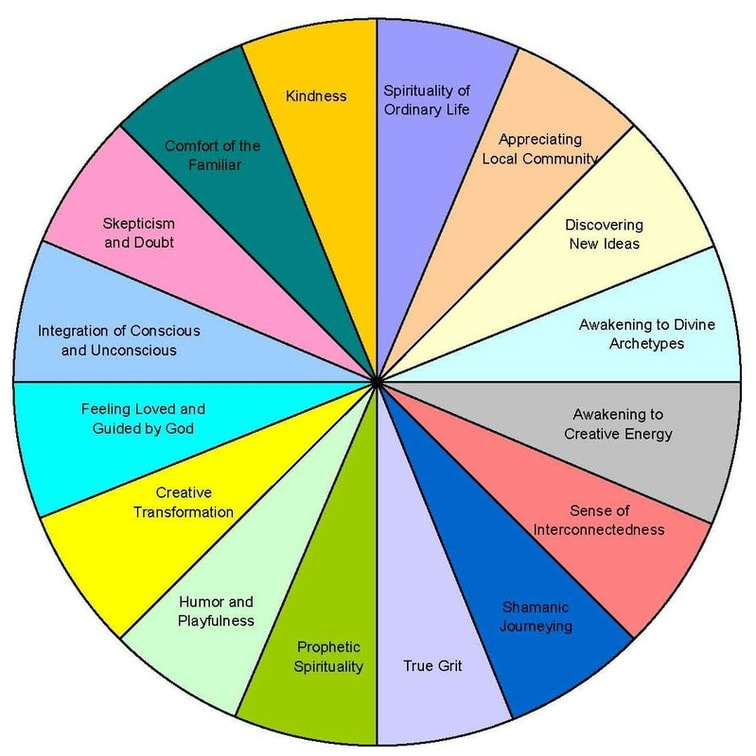

The shamanic sensibility is one of at least sixteen spiritual moods that can enrich and inform a life. It offers us a liberated imagination: that is, an imagination liberated from the mechanistic and life-destructive ways of thinking that are too often characteristic of techno-crazed western modernity, and liberated for an openness to a living universe in its visible and invisible dimensions.

But of course shamanic liberation never occurs in a vacuum. In the art of John Trudell and Patricia Adams Farmer, the spirit of shamanism is combined with humor and playfulness, an appreciation of local community, a discovery of new ideas, an awakening to the creative energy of which the universe is an expression, and a sense of connectedness.

Above all, it is connected to a hope that we humans live in fresh ways that transcend the hell made by greed, hatred, and confusion. This hope is characteristic of prophetic spirituality: that is, the spirituality that says no to unhealthy craziness and yes to a more nourishing and honest way of living in the world. Prophetic spirituality is always a little neurotic, a little crazy, a little out of sync with conventional wisdom of allegedly "sane" society. In the words of a leading process theologian, Rabbi Bradley Artson, it offers a crack that helps light enter our lives.

For process theologians God is the light that enters the crack. This light takes the form of fresh possibilities for seeing, feeling, hearing, and responding to the world, as mediated through the natural world, other people, rituals, and human artifacts (including sacred texts). The mediators are, as it were, the cracks that help us discover the light.

A discovery of this light can be playful and pleasant, but can also arise through pain and a creative transformation that comes in and after the pain. The story of John Trudell offers an image. In process theology the light is this spirit of creative transformation, and the spirit cannot be sharply separated from those who respond and cooperate with it. They may be angels, butterflies, foxes, quantum events, trees, stars, or people. They hear a song and they become a story. Along the way, if we have ears to hear, we begin to sing with them and tell stories of our own. The universe begins to flower anew, even amid the quaking and breaking of everything.

-- Jay McDaniel