Chinese Rock Music:

It Begins with Cui Jian

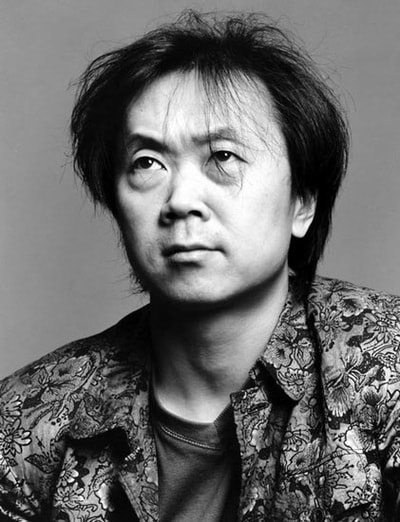

Cui Jian (崔健, born 2 August 1961) is a Beijing-based Chinese singer-songwriter, trumpeter, and guitarist. Affectionately called "Old Cui" (Chinese: 老崔; pinyin: lǎo Cuī), he is one of the first Chinese artists to write rock songs. He is often called "The Father of Chinese Rock".[1]

Cui Jian became popular after his performance of a song he wrote, “Nothing to My Name”, in late 1980s. Many of his rock songs, including “Nothing to My Name,” are love songs. These love songs were new to mainland China; they expressed feelings in an overt and spontaneous way that was foreign to a generation of young Chinese who, for almost four decades, had lost opportunities for expressing private feelings. Additionally many of his songs were interpreted as political allegories. Young Chinese were coming to think that China had taken a wrong path during and after the Cultural Revolution. Cui Jian, an icon for the popular music in 1980s and 1990s, was and remains a pioneer in China of what we might call rock for social change.

And, of course, he was very, very popular. Some fans of rock and roll in the West distinguish between rock music and pop music. They say that rock and roll has an edge to it, critiquing the status quo and offering images of a better way of living in the world for individuals and society. By contrast, they say that pop music is anesthetizing, drawing people into short-lived fantasies of romantic love at the expense of critiquing existing social condition. Often, they add, the romantic fantasies are those of adolescents and young adults. For these lovers of rock and roll, pop music is quite shallow and adolescent. It is too sentimental and insufficiently critical. It needs an edge.

Cui Jian's music has this edge. He was -- and remains -- an alternative to this questionable binary between rock and pop. Much of his music is about deeply help feelings of intimacy and longed-for intimacy (romance) and about a different kind of China: a China that is creative, compassionate, participatory, and pluralistic, with no one left behind. Often we speak of the need in China and other parts of the world for a society with these qualities. We call it an "ecological civilization,' because it includes harmony with the earth as well as kindness and respect among people. In his way Cui Jian was inaugurating the hope for ecological civilization in China, albeit pointing toward the human side of things. It's easy enough to add the ecology. For the social vision he brings to rock music, and for the pleasurable intensity of his music itself, we can only say: Keep it up! Below enjoy some of this music.

[1] http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cui_Jian

-- Wenjia Liu and Jay McDaniel

Cui Jian became popular after his performance of a song he wrote, “Nothing to My Name”, in late 1980s. Many of his rock songs, including “Nothing to My Name,” are love songs. These love songs were new to mainland China; they expressed feelings in an overt and spontaneous way that was foreign to a generation of young Chinese who, for almost four decades, had lost opportunities for expressing private feelings. Additionally many of his songs were interpreted as political allegories. Young Chinese were coming to think that China had taken a wrong path during and after the Cultural Revolution. Cui Jian, an icon for the popular music in 1980s and 1990s, was and remains a pioneer in China of what we might call rock for social change.

And, of course, he was very, very popular. Some fans of rock and roll in the West distinguish between rock music and pop music. They say that rock and roll has an edge to it, critiquing the status quo and offering images of a better way of living in the world for individuals and society. By contrast, they say that pop music is anesthetizing, drawing people into short-lived fantasies of romantic love at the expense of critiquing existing social condition. Often, they add, the romantic fantasies are those of adolescents and young adults. For these lovers of rock and roll, pop music is quite shallow and adolescent. It is too sentimental and insufficiently critical. It needs an edge.

Cui Jian's music has this edge. He was -- and remains -- an alternative to this questionable binary between rock and pop. Much of his music is about deeply help feelings of intimacy and longed-for intimacy (romance) and about a different kind of China: a China that is creative, compassionate, participatory, and pluralistic, with no one left behind. Often we speak of the need in China and other parts of the world for a society with these qualities. We call it an "ecological civilization,' because it includes harmony with the earth as well as kindness and respect among people. In his way Cui Jian was inaugurating the hope for ecological civilization in China, albeit pointing toward the human side of things. It's easy enough to add the ecology. For the social vision he brings to rock music, and for the pleasurable intensity of his music itself, we can only say: Keep it up! Below enjoy some of this music.

[1] http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cui_Jian

-- Wenjia Liu and Jay McDaniel

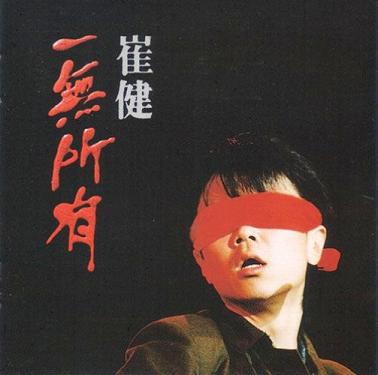

Chinese rock star Cui Jian begins his song "The 90s" with the line: "Words are not precise already—can't express this world clearly." ...His lyrics are vague enough that they can be defended as lonely love songs, and yet precise enough to be bone-cuttingly stark political anthems...When he created Chinese rock in the 1980s, Cui Jian changed the landscape of youth culture forever, and inspired a new Chinese conversation. The vocabulary for that conversation is like Cui Jian: simultaneously subtle and laceratingly direct. His art comes out of an eclectic collage of traditions: classical music, gauzy Chinese pop ballads, Western rock, and most recently rap and hip-hop. His lyrics come from language that spans a wide band: Cultural Revolution slogans, modern propaganda, the jingles of commercialization, and rough-hewn Beijing street slang....In the early eighties he became increasingly passionate about Western rock music, which was seeping through China's slightly open door, usually in the backpacks of foreign students and tourists. Cui Jian spent the eighties listening to Simon and Garfunkel, Bob Dylan, the Rolling Stones, the Beatles and the Talking Heads. He learned to play guitar and began writing music, which he played in cafés and dormitories...In May of 1986, in a televised pop music competition, Cui Jian performed what would turn out to be the biggest hit in Chinese history: "Nothing to My Name." At the otherwise pastel, romantic balladfest, he wore army fatigues and a green Communist Party of China tee shirt, sang in a gravelly voice, and ground his hips. The appearance had an Elvis Presley effect; Cui's rock sent shock waves across the country. By the following day, Chinese youth all over China were singing "Nothing to my Name"; by 1989 in Tiananmen Square, it had become their battle song. Standing in the square, Cui Jian tied a red bandana over his eyes and sang to millions of Chinese who felt like they had nothing to their names; with his words, he implied that the Chinese nation itself had nothing. No one had ever dared put it the way he did: "I keep asking endlessly/ When will you go with me?/ But you just laugh at me/ I've nothing to my name./I'll give you my dreams,/and give you my freedom./But you just laugh at me/I've nothing to my name." His music was both the most commercially popular and politically contentious in China.... |

一无所有 Nothing to My Name[1] (1986) |