- Home

- Process Worldview

- Community

- Art and Music

- Whitehead and Process Thinking

- Podcasts

- Spirituality

- Ecological Civilization

- Education

- Contact

- Social Justice

- Science

- Animals

- Sacred Poems

- Whitehead Videos

- Index of All Titles

- Practicing Process Thought

- Process Spirituality: A Spiritual Alphabet

- Recent Posts

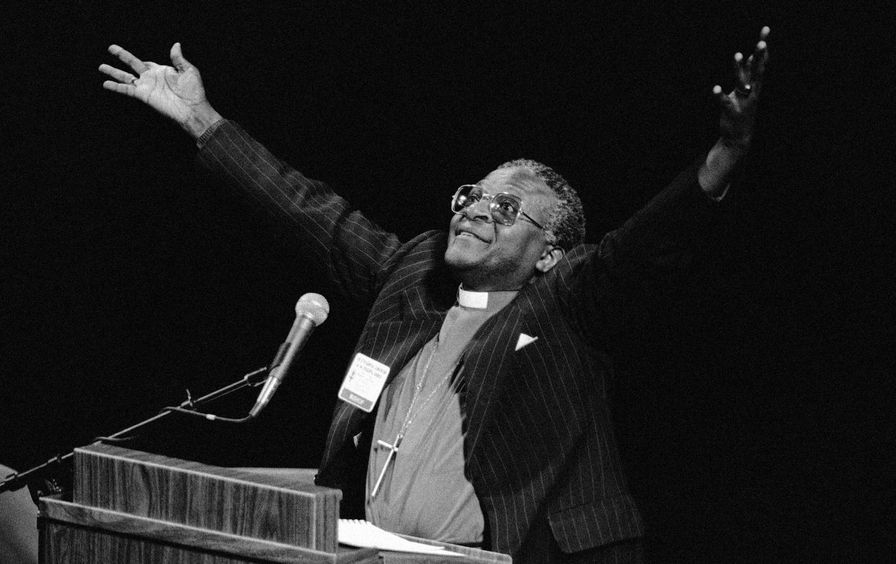

Three Cheers for Desmond Tutu's

Beautifully Fat Soul

There are at least two kinds of large selves: (1) large selves who seek to absorb all others into their individual orbits so that all things “circle” around them like planets around the sun; and (2) large selves whose generous spirit encourages others to be large selves, too.

The second kind of large self is what process theologians, influenced by Bernard Loomer, call a soul with size. Following the lead of Patricia Adams Farmer in Fat Soul Philosophy, I'll speak of the second type as a generously fat soul and the first type as an insecure suffocating soul. Here's the difference. Generously fat souls are at home in their skins; whereas large selves of the first type, oxygen-depleting or suffocating souls, are insecure in their skins, which is why they need so much attention.

Here are some characteristics of a generously fat soul.

Capacity for Loving Relationships: A fat soul enjoys range and depth in its capacity for loving relationships, helping others to become freer in their diversity and uniqueness. It is open-hearted.

Open-Mindedness: A fat soul can understand a variety of outlooks on life without feeling defensive and insecure. It is open-minded.

Openness to Complexity: A fat soul has the power to sustain complex relationships and enriching tensions. It does not lapse into either-or thinking but is inclined toward both-and thinking.

Tolerance for Enriching Tensions: A fat soul can live with enriching tensions without being overwhelmed. It does not flee from constructive conflict.

Personal Integrity: A fat soul does all this while maintaining a sense of integrity. It sticks to its principles and enjoys a sense of individual freedom.

Individuality: A fat soul does not lose its agency or self-creativity. It celebrates diversity and delights in uniqueness, and it enjoys unique agency itself.

Large selves of the second type, souls with size, are not arrogant or self-absorbed; and they are not without their faults. But they can laugh at themselves as easily as they can laugh with others. And when it's time to be unnoticed, they can step back and let relish the fact that others are in the spotlight. They can be humble. If they are introverts, they prefer not to be in the spotlight at all. Large selves of the second type, souls with size, can be extroverts or introverts or anywhere in between.

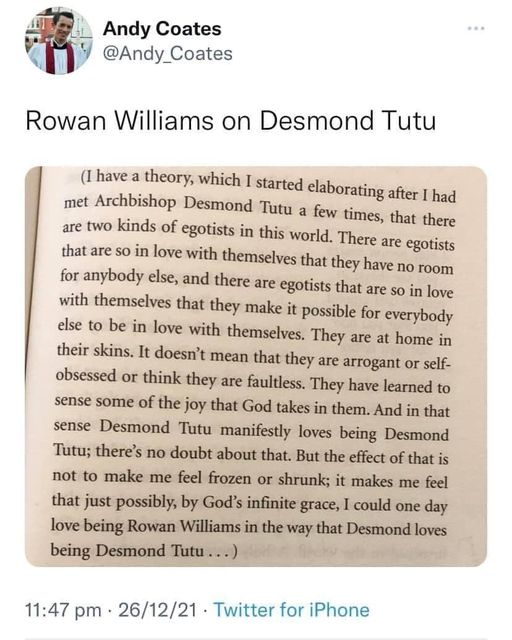

Desmond Tutu, as described by the Archbishop of Canterbury, Rowan Williams, was a large self of the second type and probably an extrovert, too, at least in his public moments. He was a generously fat soul.

Williams speaks of Tutu’s energy as “egotistical’ in a good sense, contrasting it with the energy of a large self of the first type, which is “egotistical” in a bad sense. It is doubtful that this way of speaking can easily catch on, since the word “egotistical” has negative connotations for many.

But one value of using the word in a positive sense is that it encourages us to recognize that, after all, certain kinds of self-love are very important. We best love ourselves enough, and in ways that help others love themselves, too, so that our communities grow closer to what they are called to be: compassionate communities in which everyone feels at home, and no one is left behind.

Three cheers for generously fat souls. Three cheers for Desmond Tutu's way of being a large self. In a certain sense, what the world sorely needs is more egotism of the loving kind.

- Jay McDaniel, January 1, 2022

You, Too.

attention - beauty - being present - compassion - connections - devotion - enthusiasm - faith

forgiveness - grace - gratitude - hope - hospitality - imagination - joy - justice - kindness - listening

love - meaning - nurturing - openness - peace - play - questing - reverence - shadow - silence

teachers - transformation - unity - vision - wonder - x, the mystery - yearning - you - zeal

forgiveness - grace - gratitude - hope - hospitality - imagination - joy - justice - kindness - listening

love - meaning - nurturing - openness - peace - play - questing - reverence - shadow - silence

teachers - transformation - unity - vision - wonder - x, the mystery - yearning - you - zeal

In the alphabet of spiritual literacy offered above, there are thirty-seven qualities of heart and mind that are part of humanity's spiritual vocabulary. We can be attentive or mindful, open to beauty, grateful for life, compassionate to others, connected to community, etc. The alphabet is offered by my favorite interfaith and spirituality network: Spirituality and Practice.

I think of these thirty-seven qualities as forms of emotional intelligence and practical wisdom that help us become fully alive as human beings. Process theologians add that these qualities are inspired and loved by a Great Companion in whose life the universe unfolds, often addressed as God. Not unlike a truly loving parent or grandparent, this companion takes delight in our delight; this Companion is gladdened by our full aliveness. We participate in God's life by embodying these qualities.

Some might think that all thirty-seven qualities are forms of ego-loss or ego-denial, or that they are primarily and exclusively about morality. Certainly some of them are: compassion, forgiveness, justice, and kindness, for example, But not all of them. One of them, for example, is what Spirituality and Practice calls You.

Rowan Williams says that Desmond Tutu had a large and capacious You. We in the process world speak of capacious Youness as width of soul. Bernard Loomer puts it this way:

"By S-I-Z-E I mean the stature of [your] soul, the range and depth of [your] love, [your] capacity for relationships. I mean the volume of life you can take into your being and still maintain your integrity and individuality, the intensity and variety of outlook you can entertain in the unity of your being without feeling defensive or insecure. I mean the strength of your spirit to encourage others to become freer in the development of their diversity and uniqueness. I mean the power to sustain more complex and enriching tensions. I mean the magnanimity of concern to provide conditions that enable others to increase in stature."

- Bernard Loomer

This page is an invitation to appreciate a spirituality of You-ness, understanding it as akin to the healthy egotism of, say, Desmond Tutu as described by Rowan Williams. Healthy egotism is a sizeable soulhood that reaches out and helps others find their You, too.

The Spiritual Practice of You

Frederic and Mary Ann Brussat

"Each of us is a work-in-progress. The spiritual practice of you challenges us to become all we are meant to be as God's beloved sons and daughters. We are, after all, co-creators of the Great Work of the universe. By attuning ourselves to what in different traditions has been called the image of God, the everlasting soul, or the higher self, we are able to fulfill our mission in life.

All the world's religions refer to the civil war that rages inside us when self-absorption meets self-regard and selfishness clashes with selflessness. The spiritual life requires that we think enough of ourselves to believe we can serve others without putting ourselves above them. It's sometimes a tricky balance to maintain.

Begin with what is right in front of you. Have both pride and humility. Be assertive and yielding. You are much more and much less than you probably think you are. Relax. This, the Creator reminds us, is good."

All the world's religions refer to the civil war that rages inside us when self-absorption meets self-regard and selfishness clashes with selflessness. The spiritual life requires that we think enough of ourselves to believe we can serve others without putting ourselves above them. It's sometimes a tricky balance to maintain.

Begin with what is right in front of you. Have both pride and humility. Be assertive and yielding. You are much more and much less than you probably think you are. Relax. This, the Creator reminds us, is good."

Three Cheers for Emmanuel Ofosu Yeboah's Fat Soul, Too

Emmanuel's Gift

Directed by Lisa Lax, Nancy Stern

An inspiring documentary about a determined young man

who almost single-handedly has changed the way the disabled are treated in Ghana.

Film Review by Frederic and Mary Ann Brussat

Reposted from Spirituality and Practice

In Ghana, Africa, babies who are born with disabilities are usually poisoned or abandoned by their parents to die alone. There are roughly two million disabled people in the country — which is about ten percent of the total population. Since these unfortunate individuals are believed to live under a curse, they are not allowed to work. All that is left for them is a life of begging on the streets. But now, thanks to one man, all that is slowly beginning to change.

Filmmakers Lisa Lax and Nancy Stern have made an inspiring documentary about Emmanuel Ofosu Yeboah, a charismatic and determined young man who was born with a malformed right leg but refused to allow this disability to slow him down or ruin his life.

Despite the fact that her husband left once Emmanuel was born, his mother decided that she would send him to school. Even though he faced prejudice and ridicule, this young boy even managed to become an athlete. In order to earn the money needed to take care of his mother, Emmanuel dropped out of school and left his small farming village for the large city of Accra. There he shined shoes for two dollars a day and sent the money home.

After the death of his mother who believed so strongly in him, Emmanuel decided to try to do something to change the attitudes of his countrymen toward disabled people. He applied to the Challenged Athletes Foundation in San Diego, California and received a mountain bike which he then road with his one leg on a journey across Ghana to raise people's consciousness about those born with physical deformities.

Emmanuel eventually travels to America , participates in some athletic competitions, and is eventually fitted with a prosthetic leg. At fundraising triathlons, he meets other disabled individuals who share his view that sports provides a great arena for testing oneself and accomplishing great things. Returning home to Ghana, Emmanuel receives a hero's welcome and then expands his work for the disabled by getting wheelchairs for many people, convincing an African king to host a party for him and his friends (a big step in influencing politicians to take another look at the shameful discrimination against the handicapped), and starting a program that offers scholarships to disabled children.

From start to finish, this documentary shows how one person driven by a passion can make a difference in the lives of others. Oprah Winfrey narrates Emmanuel's Gift.