- Home

- Process Worldview

- Community

- Art and Music

- Whitehead and Process Thinking

- Podcasts

- Spirituality

- Ecological Civilization

- Education

- Contact

- Social Justice

- Science

- Animals

- Sacred Poems

- Whitehead Videos

- Index of All Titles

- Practicing Process Thought

- Process Spirituality: A Spiritual Alphabet

- Recent Posts

Divine Inscrutability

Countee Cullen's "Yet Do I Marvel"

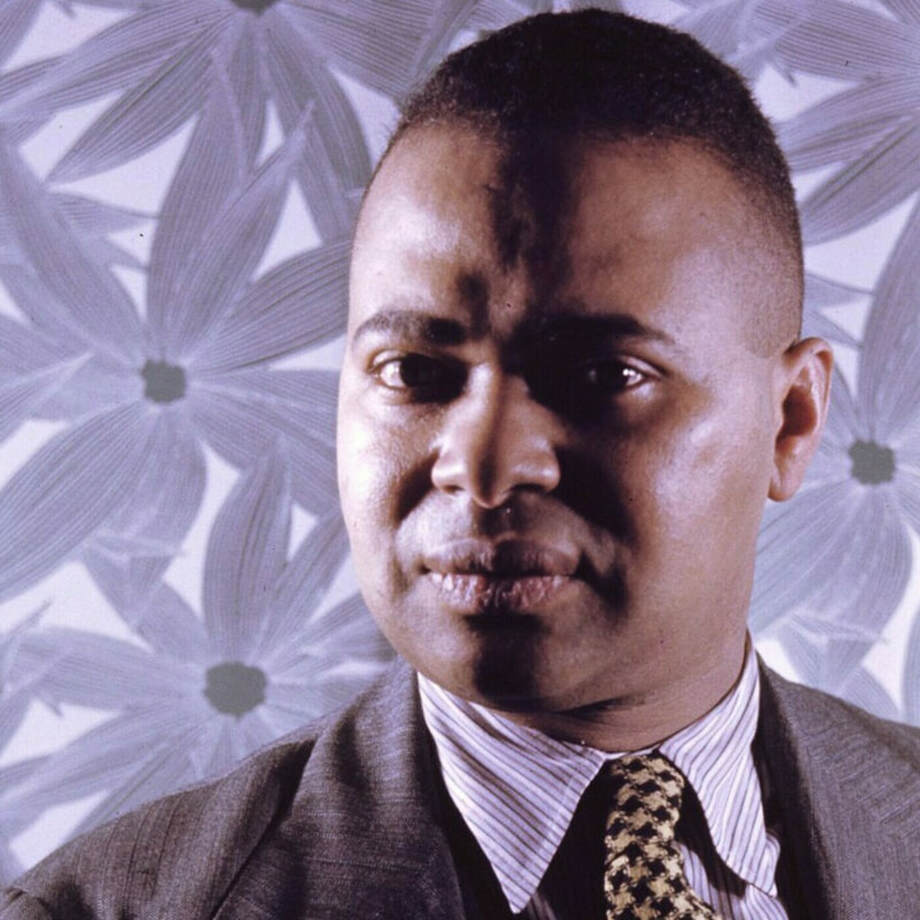

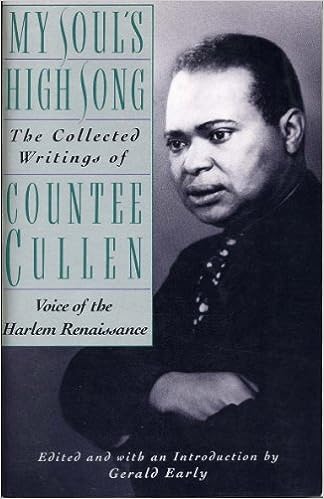

Countee Cullen (1903-1946), a prominent figure during the Harlem Renaissance of the 1920s, understands the cosmic injustice embedded in racial prejudice. As a Christian, he maintains faith in God's goodness and kindness despite this injustice, but he candidly acknowledges the inscrutable nature of God's ways. The very enigma within and behind the world—God—possesses an "awful brain" that compels its "awful hands" to permit such evils. And then Cullen adds:"Yet do I marvel at this curious thing/To make a poet black, and bid him sing!"

While the word "marvel" could be interpreted as a forceful and pious proclamation, the phrase "a curious thing" tempers this interpretation. The marveling in question assumes a more subdued tone, infused with a sense of ambiguity. It is "curious" that God would bring forth a black poet in a world with so much pain, almost as if it were a misstep. Behind it all lies divine inscrutability.

Open and relational theologians might hastily respond by claiming to have resolved the dilemma of evil. They propose that God is all-loving but not all-powerful, suggesting that many events in the world surpass God's control.

While this perspective may contain some truth, it deviates from the core message of the poem. The essence of the poem resides in presenting a moment of audacious questioning and conveying an emotion—marveling at goodness in the face of divine inscrutability—that is holy in its own right and requires no resolution. The sanctity exists in the act of marveling, in being sensitive to the capricious side of life, in holding the two together without allowing one to collapse into the other, and in being honest about divine inscrutability. A significant peril of open and relational theology is its presumption that we require answers about God and life when, in reality, there is holiness in the questioning.

- Jay McDaniel

While the word "marvel" could be interpreted as a forceful and pious proclamation, the phrase "a curious thing" tempers this interpretation. The marveling in question assumes a more subdued tone, infused with a sense of ambiguity. It is "curious" that God would bring forth a black poet in a world with so much pain, almost as if it were a misstep. Behind it all lies divine inscrutability.

Open and relational theologians might hastily respond by claiming to have resolved the dilemma of evil. They propose that God is all-loving but not all-powerful, suggesting that many events in the world surpass God's control.

While this perspective may contain some truth, it deviates from the core message of the poem. The essence of the poem resides in presenting a moment of audacious questioning and conveying an emotion—marveling at goodness in the face of divine inscrutability—that is holy in its own right and requires no resolution. The sanctity exists in the act of marveling, in being sensitive to the capricious side of life, in holding the two together without allowing one to collapse into the other, and in being honest about divine inscrutability. A significant peril of open and relational theology is its presumption that we require answers about God and life when, in reality, there is holiness in the questioning.

- Jay McDaniel

Yet Do I Marvel

BY COUNTEE CULLEN

I doubt not God is good, well-meaning, kind,

And did He stoop to quibble could tell why

The little buried mole continues blind,

Why flesh that mirrors Him must some day die,

Make plain the reason tortured Tantalus

Is baited by the fickle fruit, declare

If merely brute caprice dooms Sisyphus

To struggle up a never-ending stair.

Inscrutable His ways are, and immune

To catechism by a mind too strewn

With petty cares to slightly understand

What awful brain compels His awful hand.

Yet do I marvel at this curious thing:

To make a poet black, and bid him sing!

Countee Cullen, “Yet Do I Marvel” from Color. Copyright 1925 by Harper & Brothers, NY. Renewed 1953 by Ida M. Cullen. Copyrights held by The Amistad Research Center, Tulane University. Administrated by Thompson and Thompson, Brooklyn, NY.

Cullen's Aesthetic:

Art Transcends Race

"Because of Cullen’s success in both black and white cultures, and because of his romantic temperament, he formulated an aesthetic that embraced both cultures. He came to believe that art transcended race and that it could be used as a vehicle to minimize the distance between black and white peoples. When he chose as his models poet John Keats and to a lesser extent A.E. Housman, he did so not consciously to curry favor with white America but for four logical reasons: First, though there had been African American poets, there was not yet an African American poetic tradition—in any meaningful sense of the term—to draw upon. Second, the English poetic tradition was the one that was available to him—the one that had been taught to him in schools he attended. Third, he felt challenged to demonstrate that a black poet could excel within that traditional framework. And fourth, he felt absolutely free to choose as exemplars any poets in the world with whom he sensed a temperamental affinity (and he certainly had that affinity with Housman and, especially, Keats). In addition, he shared their romantic self-involvement; he had an ego that was sensitive to the slightest tremors and that needed expression to remain whole, and like Keats he had to believe in human perfectibility."

- The Poetry Foundation

- The Poetry Foundation

God's Astonishing Miscue

Those who overlook Cullen’s strong indictment of racism in American society miss the main thrust of his work. His poetry throbs with anger as in “Incident” when he recalls his personal response to being called “nigger” on a Baltimore bus, or in the selection “Yet Do I Marvel,” in which Cullen identifies what he regards as God’s most astonishing miscue that he could “make a poet black, and bid him sing!”

- The Poetry Foundation

- The Poetry Foundation

Poems by Countee Cullen

- A Brown Girl Dead

- Epitaphs

- For Amy Lowell

- From the Dark Tower

- Heritage

- Incident

- Karenge ya Marenge

- Lines to My Father

- Saturday’s Child

- Simon the Cyrenian Speaks

- Thoughts in a Zoo

- Three Epitaphs

- Threnody for a Brown Girl

- To Certain Critics

- To the Swimmer

- Two Thoughts of Death

- The Wind Bloweth Where It Listeth

- Yet Do I Marvel