- Home

- Process Worldview

- Community

- Art and Music

- Whitehead and Process Thinking

- Podcasts

- Spirituality

- Ecological Civilization

- Education

- Contact

- Social Justice

- Science

- Animals

- Sacred Poems

- Whitehead Videos

- Index of All Titles

- Practicing Process Thought

- Process Spirituality: A Spiritual Alphabet

- Recent Posts

Don't Never Tell Nobody

Not to Use No Double Negatives

Process Theology, Linguistic Imperialism,

and the Liberation of Grammar

Linguistic Prejudice

Language use is one of the last places where prejudice remains socially acceptable. It can even have official approval, as we see in attempts to suppress slang and dialects at school...Native speakers of English are generally at least bidialectal. We have the dialect we grew up using, with its idiosyncrasies of vocabulary, grammar and pronunciation, and we learn standard English at school and through media like books and radio. As with any social behaviour, we pick up linguistic norms and learn to code-switch according to context. Just as we may wear a T-shirt and slippers at home, but a suit and shoes at work, so we adjust our language to fit the situation.

- Stan Carey

Grammatical Imperialism

Imagine a world in which a cultured elite rules over non-dominant social and economic classes by insisting on a correct way of speaking. Imagine also that this "correct" way is encoded in formal education and taught as "standard," meaning that that alternative ways which "break the rules" of standard speech are demeaned, and the people who use them are stigmatized as slovenly, vulgar, barbarous, or ignorant by the elite. Imagine, in other words, our world.

The cultured elite forget, or conveniently neglect to acknowledge, that grammatical rules do not drop from heaven, they emerge from how people use language. Would that they had all read the later Wittgenstein.

Now imagine that the universe itself is an evolving network of mutual becoming, such that all kinds of entities - atoms, molecules, planets, plants, animals, and people - evolve different grammars, different habits of self-expression, relative to the contexts of their becoming. These habits are called, abstractly, the laws of nature, but even these laws do not drop from heaven; nor are they fixed. The habits are evolving, too. Some may last for billions of years, but even they are in process. Would that those who believe the contrary had all read Whitehead.

Consider then the idea that the universe itself has a mind or soul: an intelligent Life in whose consciousness the universe lives and moves and has its being. Think of this Life as on the side of life itself, wherever it is. On our small planet or on planets surrounding other stars. It wants, it hopes, that they will flourish. In the case of lives such as our own, it hopes that they will awaken to the fact that language itself is contextual and, deep down, poetic and metaphorical. Its function is to serve life, not the other way around. It seeks their satisfaction, however momentary. Think of this Life as God.

Perhaps, in relation to life on Earth, this Life is hopeful that we humans will learn to live lightly on the Earth and gently with one another, free from prejudice and free for love. Our imaginations will be flexible and open, such that we avoid altogether the idea that we hear the grammars of many forms of life, appreciating that they have languages of their own. We will be, as it were, eco-grammatical in our approach to life. And our imagines will celebrate, not flee from, the idea that there are many different and beautiful grammars in human life, none superior to others and each with their gifts. This Life will dwell within each human being as an inwardly felt lure to celebrate the different ways of speaking and to reject the idea that anyone "ought" to speak in the power-imposing and dominating way. Its hidden call, anywhere and everywhere, will be: "Don't never tell nobody not to use no double negatives."

- Jay McDaniel

The cultured elite forget, or conveniently neglect to acknowledge, that grammatical rules do not drop from heaven, they emerge from how people use language. Would that they had all read the later Wittgenstein.

Now imagine that the universe itself is an evolving network of mutual becoming, such that all kinds of entities - atoms, molecules, planets, plants, animals, and people - evolve different grammars, different habits of self-expression, relative to the contexts of their becoming. These habits are called, abstractly, the laws of nature, but even these laws do not drop from heaven; nor are they fixed. The habits are evolving, too. Some may last for billions of years, but even they are in process. Would that those who believe the contrary had all read Whitehead.

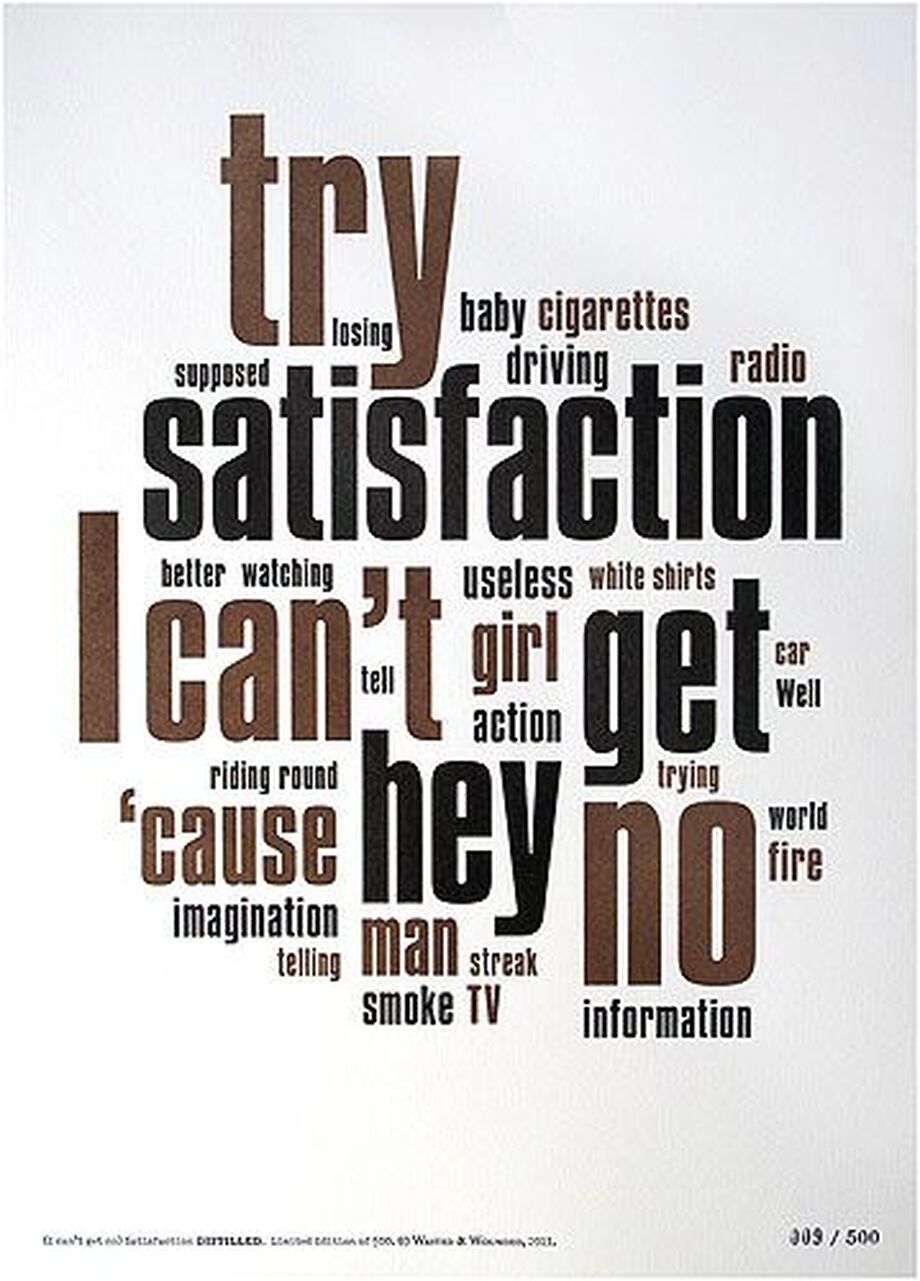

Consider then the idea that the universe itself has a mind or soul: an intelligent Life in whose consciousness the universe lives and moves and has its being. Think of this Life as on the side of life itself, wherever it is. On our small planet or on planets surrounding other stars. It wants, it hopes, that they will flourish. In the case of lives such as our own, it hopes that they will awaken to the fact that language itself is contextual and, deep down, poetic and metaphorical. Its function is to serve life, not the other way around. It seeks their satisfaction, however momentary. Think of this Life as God.

Perhaps, in relation to life on Earth, this Life is hopeful that we humans will learn to live lightly on the Earth and gently with one another, free from prejudice and free for love. Our imaginations will be flexible and open, such that we avoid altogether the idea that we hear the grammars of many forms of life, appreciating that they have languages of their own. We will be, as it were, eco-grammatical in our approach to life. And our imagines will celebrate, not flee from, the idea that there are many different and beautiful grammars in human life, none superior to others and each with their gifts. This Life will dwell within each human being as an inwardly felt lure to celebrate the different ways of speaking and to reject the idea that anyone "ought" to speak in the power-imposing and dominating way. Its hidden call, anywhere and everywhere, will be: "Don't never tell nobody not to use no double negatives."

- Jay McDaniel

Don’t never tell nobody

not to use no double negatives

by Stan Carey

from Sentence First: An Irishman's Blog

about the English Language

excerpts

Language and Power

Negative concord is stigmatized today because it’s prohibited in standardized English and associated with people from non-dominant socioeconomic and ethnic populations: working-class people and people of colour. And language has always been a convenient proxy for social prejudice. Norman Fairclough, Language and Power:

Standard English was regarded as correct English, and other social dialects were stigmatised not only in terms of correctness but also in terms which indirectly reflected on the lifestyles, morality and so forth of their speakers, the emergent working class of capitalised society: they were vulgar, slovenly, low, barbarous, and so forth. . . . The codification of the standard was a crucial part of this process, which went hand-in-hand with prescription, the designation of the forms of the standard as the only ‘correct’ ones.

Standard English was regarded as correct English, and other social dialects were stigmatised not only in terms of correctness but also in terms which indirectly reflected on the lifestyles, morality and so forth of their speakers, the emergent working class of capitalised society: they were vulgar, slovenly, low, barbarous, and so forth. . . . The codification of the standard was a crucial part of this process, which went hand-in-hand with prescription, the designation of the forms of the standard as the only ‘correct’ ones.

Politics of use

Be wary, then, when you see Aristotelian logic applied to language use, especially to enforce a specious ‘rule’ that just happens to target informal or non-standardized language. This strategy mischaracterizes language and often smuggles value judgements of people disproportionately excluded from prevailing power structures.

The stigma against negative concord in English is social and political, not grammatical. But it’s been repeated so often, for so long, that it has seeped into conventional belief along with dozens of other superstitions, zombie rules, and myths about English usage.

Negative concord is not a flaw in the countless varieties of English that use it. It’s a systematic, age-old grammatical feature with pragmatic or expressive purpose. Double negatives generally only ‘cancel out’ in contexts where that intent is obvious,6 or in dubious fantasies of a more orderly tongue.

Grammar rules emerge from how people use language. Invented rules asserted as dogma may have social utility but have no underlying authority. Context is vital: obviously NC is not normally suited to job applications and the like – though increasingly there are jobs where it makes no difference, and that’s fine.

Many people whose dialect lacks NC still draw on it in informal chat with friends and family, often in jest or through set phrases like ain’t no thing or it don’t make no never mind. This vernacularisation is available to us all, part of the great diversity of conversational modes.

Negative concord is unlikely to become part of standardized English any time soon, if ever – its status as a shibboleth is too entrenched. But if it’s part of your everyday or occasional usage, know that there ain’t no grammatical or linguistic reason to discard it or feel bad about it.

Swimming in Expressive Abundance

Linguist Arnold Zwicky has written regularly about what he calls “One Right Way” – the common but erroneous belief that an expression has only one permissible meaning, or that a meaning has only one permissible form. The principle, Zwicky says, is used to object to lexical innovations. So if you mean before in a temporal sense, you have to use before: other phrases, such as ahead of, are not allowed to mean this, and must be treated as impostors.

This rigid approach is out of step with what language is and how people use it – it’s like trying to impose a uniform on public clothing habits. One of the great things about language is that it gives us so many options. We swim in expressive abundance, often being able to choose from several ways to say more or less the same thing. The luxury of alternatives allows us to deliver particular connotations or nuances with a given phrase, depending on our practical and pragmatic needs.

- Stan Carey

This rigid approach is out of step with what language is and how people use it – it’s like trying to impose a uniform on public clothing habits. One of the great things about language is that it gives us so many options. We swim in expressive abundance, often being able to choose from several ways to say more or less the same thing. The luxury of alternatives allows us to deliver particular connotations or nuances with a given phrase, depending on our practical and pragmatic needs.

- Stan Carey