- Home

- Process Worldview

- Community

- Art and Music

- Whitehead and Process Thinking

- Podcasts

- Spirituality

- Ecological Civilization

- Education

- Contact

- Social Justice

- Science

- Animals

- Sacred Poems

- Whitehead Videos

- Index of All Titles

- Practicing Process Thought

- Process Spirituality: A Spiritual Alphabet

- Recent Posts

|

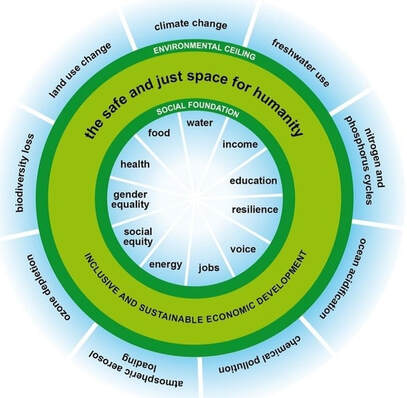

The Doughnut, or Doughnut economics, is a visual framework for sustainable development – shaped like a doughnut – combining the concept of planetary boundaries with the complementary concept of social boundaries. The framework was proposed to regard the performance of an economy by the extent to which the needs of people are met without overshooting Earth's ecological ceiling. The name derives from the shape of the diagram, i.e. a disc with a hole in the middle. The centre hole of the model depicts the proportion of people that lack access to life's essentials (healthcare, education, equity and so on) while the crust represents the ecological ceilings (planetary boundaries) that life depends on and must not be overshot.

Consequently, an economy is considered prosperous when all twelve social foundations are met without overshooting any of the nine ecological ceilings. This situation is represented by the area between the two rings, namely the safe and just space for humanity. The diagram was developed by Oxford economist Kate Raworth in the Oxfam paper A Safe and Just Space for Humanity and elaborated upon in her book Doughnut Economics: Seven Ways to Think Like a 21st-Century Economist. |

|

Kate Raworth as a voice

for Planetary Economics by John Cobb. co-author with Herman Daly of For the Common Good The most important discussions in shaping actual policies and actions around the world are those about economics. Sadly, they are still carried on in classical ways, generally now, in terms of neo-liberalism. As long as this continues, the world will continue to head toward catastrophe. Far better alternatives have been offered. The most important is that of Herman Daly. But he and his followers are largely ignored. In departments of economics, the default position has not been affected. Ecological economics is marginal, and since this margin cannot be rationally defeated, it is not discussed. There is another margin. Among those economists who are dealing concretely with real problems, especially in the "developing" world, many are open to considering ideas that are in tension with neo-liberal economics. Kate Raworth speaks to their concerns, and they are listening. This margin is growing. It is still largely ignored in the academy, but it has the ear of governments and even businesses. It may not be possible in the long run for academics simply to ignore it. Once there is serious discussion of Raworth's work, change will be rapid. Neo-liberals cannot hold their own in debate, once the issues are presented clearly and forcefully as by Raworth. Our task is to keep attention focused on her ideas despite their continued marginalization in the academy. There is a chance, probably not a probability, that the authorities will listen and professional economists will begin to help us find a way that leads away from catastrophe. Thank you, Kate |

A Review of Doughnut Economics

Herman Daly, the father of eco-economics, reviews Kate Raworth’s Doughnut Economics (Green Publishers, 2017). By Herman E. Daly In spite of its title, Doughnut Economics is a serious book by someone with a strong background in both academic economics and development policy. Writing in a clear and engaging style, Kate Raworth explains to the general public and students what is wrong with the standard curriculum in economics, and how to break out of that monopolized mental prison. It is likely a waste of time to address arguments to economics professors, including some of her tutors at Oxford, although honesty demands that we still do it. One might think that only old economists are beyond reach, while young ones are open-minded. My experience, however, is that the old teachers have been very successful in producing identical clones in the younger generation. They do this by narrowing the curriculum to exclude whatever subject matter raises problems. Philosophy and epistemology were excluded early on–no more troublesome courses in “methodology.” Next, the history of economic though was eliminated–why study the errors of the past when you know the truth? Economic history was banished to the history department–not rigorous enough. Then comparative economic systems was jettisoned with the triumph of capitalism–there is no alternative. The space opened by these omissions was filled by mathematics, which lent a façade of scientific respectability to the economists’ retreat to hide in thickets of algebra while leaving the important questions to journalists, to paraphrase Joan Robinson. When a relatively young, but experienced, economist defects from this weak and cowardly army, it is a cause for celebration, and for hope that more defectors will follow. The main epiphany for Raworth is the realization that the economy has both a biophysical ceiling and an ethico-social floor, and that the Keynesian-neoclassical growth synthesis tends to violate both of these limits. Raworth’s specific defections are discussed in seven topical chapters. Briefly, these include:

By the last I think Raworth means not automatically attaching the adjective “economic” to the noun “growth” anytime the economy grows in its physical scale relative to the containing ecosphere. Physical growth of the economy can be, and in some countries is, uneconomic growth, in the sense that it increases environmental and social costs faster than production benefits. And the world as a whole is likely engaged in uneconomic growth if costs and benefits were properly measured. I highly recommend the book, especially to university economics students. If there is to be a second edition, and I hope there will be, I would like to see a further analysis of the seventh point–less agnosticism and more clarification of economic versus uneconomic growth. In addition, a more critical discussion of the slogan “circular economy” would be welcome since it ultimately conflicts with entropy (noted in passing, but not discussed), and does not fit comfortably with her earlier critique of the famous circular flow diagram. More attention to population growth would be good. Also an index would be helpful. Herman E. Daly is Emeritus Professor, School of Public Policy, University of Maryland |

Seven One-Minute Videos explaining

Raworth's Doughnut Economics

|

|

|

|