Emerging Hopes in China

The Sunshine Eco-Village, Process Philosophy,

and the Resurrection of Tao Yuanming

.

Contents of Page

|

1. Why This Page?

|

A Word from Jay McDaniel

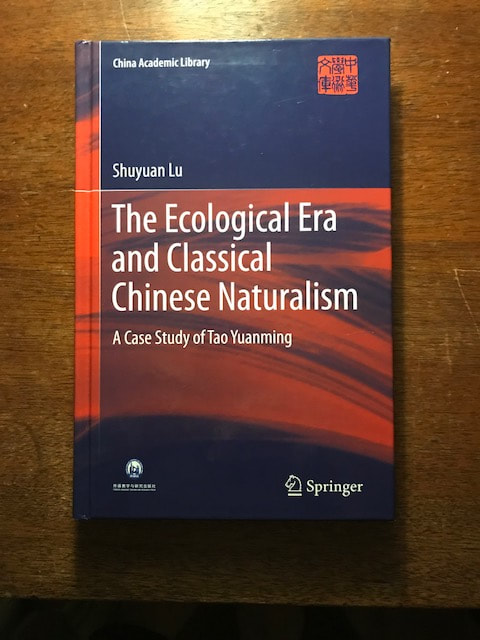

In The Ecological Era and Classical Chinese Naturalism: A Case Study of Tao Yuanming, Professor Shuyuan Lu proposes that the great Chinese nature poet, Tao Yuanming, can be "resurrected" when people reclaim their felt bonds with the more-than-human world and live accordingly. This page offers two illustrations of that resurrection: the inspirational work of the Sunshine International Eco-Village in Zhejiang Province and that of Process Philosophers in China. Along the way I explain what process thinking is for those who do not know it. Readers might also be interested in another page on this site: Open Horizons China. At the end of the page, I offers a "process" appreciation of core themes in Professor Lu's book. (Jay McDaniel) |

A Word from John Cobb

"Many of us speak generally and appreciatively of classical Chinese thought and of its potential relevance to our time and need. Some of us know that there was a great Chinese thinker by the name of Tao Yuanming whose thought especailly significant and useful form to the Chinese tradition. Now Professor Lu Shuyuan has not only described that thought in nuanced detail but located it in relation to Western thnkers so as to display the value of Tao Yuanming's insights." (John B. Cobb Jr.) |

2. Audio Version of Peach Blossom Spring (in English)

English Version of "Peach Blossom Spring"

by Tao Yuanming (365-427)

3.. The Sunshine International Eco-Village in Zhejiang Province

"Ecovillages are traditional or intentional communities whose goal is to become more socially, culturally, economically and ecologically sustainable. Ecovillages are consciously designed through locally owned, participatory processes to regenerate and restore their social and natural environments. Most range from a population of 50 to 150 individuals, although some are smaller, and traditional ecovillages are often much larger. Larger ecovillages often exist as networks of smaller subcommunities. Certain ecovillages have grown by the addition of individuals, families, or other small groups who are not necessarily members settling on the periphery of the ecovillage and effectively participating in the ecovillage community." (Wikipedia)

|

The Sunshine Eco-Village in its own Words:

"As a certificated Eco-village and a member of GEN (Global Eco-village Network ), Sunshine Eco-village Network ( SEN ) has been building the first base in Xuling Hangzhou for 1.5 years as a Chinese local eco-village. We focus on three essentials: lifestyle, ecology and life. We practice how to build a real eco-village from four aspects of Ecology, Economy, Community and Culture under the EDE (Eco-village Design Education ) system of GEN and Gaia Education. We combine Chinese traditional lifestyle wisdom and culture with the international eco-village building theory and try to find a good way to regenerate 100 eco-villages in China in future. Our emphases are on Ecology, Localized Economy, Community, and Culture (Chinese traditional culture including Taoism, Tea Art, Chin, Bow and Arrow Art, Traditional Chinese Medicine, International culture exchanging and communicating. We believe the Eco-village is one of the best solutions to practice global sustainable development. In Sunshine Eco-village, we have 10 children from 6 moths to 14 years old and we have a green school. When we are building our village, they are quite active and offered a lot of brilliant ideas and inspired us. From our sight, children have different eyes and words, they are more natural and direct to the essence of the world. Watching this second generation for future eco-village, we cannot help asking: What kind of eco-village will be if it is built by children? We are really curious and would like to give it a try! We can give our children an opportunity to start their eco-village now. We call ourselves Sunshine International Eco-village and we do believe that global could be a village, better eco-village : ) We do receive a lot of foreign families from both Europe and East Asia and share a lot of wonderful moments together in our valley. A fact we are facing is our children will not be living alone in our own country all the time. To learn more about other countries' culture or even languages become quite important for all our children. Another important reason is we will not fight with our friends or because of misunderstanding of each other’s culture, right? -- https://mp.weixin.qq.com/s/GDcFBvwlvc58AD7MYQz-IQ |

4. The Resurrection of Tao Yuanming

reclaiming the classical Chinese arts for the 21st Century

"Tao Yuanming's (365-427) philosophy of "knowing the bright but cleaving to the dark," his abandon, aloofness, and serenity, his romantic resignation to Nature's transformation, his returning to Nature his pure and simple tianyuan, and his honest poverty, ease, and idling - could all of these inspire people today?...Will Tao be resurrected?" (Shuyuan Lu)

*

Tao Yuanming will be resurrected only if, and when, significant numbers of people in China and other parts of the world remember that they are small but included in a much larger whole - a whole that includes the hills and rifers, the trees and stars. And he will be resurrected only if, and when, amid their remembrance, they learn to live lightly on the earth and gently with one another, avoiding the twin evils of the modern era: rootless consumerism on the one hand and religious fundamentalism on the other.

Even as they -- we -- might strive to believe in certain truths, we will hold convictions with a relaxed grasp, knowing that the brightness of the daytime world is nested within the nourishing darkness of the Way of the universe. We will know the bright but cleave to the dark.

With these sensibilities in mind, we can then reclaim a healthy balance between the vibrancy of urban life and the profound dignity of rural life, including the dignity of farming. At night, after a day's work, we may drink a glass of local wine, and tell stories, and laugh. We will befriend one another even as they befriend the earth.

We may simultaneously seek some kind of philosophy, some outlook on life, by which we can affirm the wisdom of their own bodies, the wisdom of animals, the wisdom of the sages, the wisdom of the stars. This philosophy will remind them that all living being -- all of them -- have value worthy of respect and care. It will remind us that the trees have voices, too. It will be a philosophy that sees feeling in energy and energy in feeling.

This philosophy is now waiting to be born in the hearts and minds of people all over the world. It is itself a way of living - a way that moves beyond the destructive sides of modernity into the constructive sides of a postmodern world. The philosophy of Alfred North Whitehead provides a powerful hint of it, as does Heidegger's idea that we humans might "dwell poetically in the world." But the poetry of Tao Yuanming likewise provides a hint of it, and he lived many centuries before Whitehead and Heidegger.

Will Tao be resurrected? Might process philosophy help?

*

Tao Yuanming will be resurrected only if, and when, significant numbers of people in China and other parts of the world remember that they are small but included in a much larger whole - a whole that includes the hills and rifers, the trees and stars. And he will be resurrected only if, and when, amid their remembrance, they learn to live lightly on the earth and gently with one another, avoiding the twin evils of the modern era: rootless consumerism on the one hand and religious fundamentalism on the other.

Even as they -- we -- might strive to believe in certain truths, we will hold convictions with a relaxed grasp, knowing that the brightness of the daytime world is nested within the nourishing darkness of the Way of the universe. We will know the bright but cleave to the dark.

With these sensibilities in mind, we can then reclaim a healthy balance between the vibrancy of urban life and the profound dignity of rural life, including the dignity of farming. At night, after a day's work, we may drink a glass of local wine, and tell stories, and laugh. We will befriend one another even as they befriend the earth.

We may simultaneously seek some kind of philosophy, some outlook on life, by which we can affirm the wisdom of their own bodies, the wisdom of animals, the wisdom of the sages, the wisdom of the stars. This philosophy will remind them that all living being -- all of them -- have value worthy of respect and care. It will remind us that the trees have voices, too. It will be a philosophy that sees feeling in energy and energy in feeling.

This philosophy is now waiting to be born in the hearts and minds of people all over the world. It is itself a way of living - a way that moves beyond the destructive sides of modernity into the constructive sides of a postmodern world. The philosophy of Alfred North Whitehead provides a powerful hint of it, as does Heidegger's idea that we humans might "dwell poetically in the world." But the poetry of Tao Yuanming likewise provides a hint of it, and he lived many centuries before Whitehead and Heidegger.

Will Tao be resurrected? Might process philosophy help?

5. Process Philosophy in Five Sentences

Process Thinking in Five Chinese Sentences

1. 一切皆在联系中,一个现实实有存在于其它现实实有之中。 |

A Very Rough Paraphrase in English1. Everything is connected to everything else: every actual entity is present in every other actual entity even as each entity is also unique. |

6. Further Reflections on Sunshine Village

|

This is Karen in the photo, offering me some locally made wine at a remote village in the Zhejiang Province of Eastern China. She is explaining how it is made.

A growing number of young Chinese (ages 20 to 45) are drawn to living in, and helping build, eco-villages. In The Ecological Era and Classical Chinese Naturalism, Professor Shuyuan Lu puts this in perspective. He discusses a movement in China called the "Freeter" movement in which young Chinese decide that, all things considered, they would rather live without material ambition or aspiration, working minimally, and enjoying whatever leisure is possible for them. Abandoning the example of their fathers, they "refuse to dedicate themselves entirely to their work," and many do so for spiritual reasons: "The meaning of their lives begins to return to life itself." Lu sees them as connected in their way to the same aspirations that inspired Thoreau in the West and the poet Tao Yangming in China: "It seems that Thoreau and Tao dwell in them." By this he means that their hearts are drawn by a desire to return to the womb of existence and live from its nourishment: the Dao. "Man's aspirations to naturalness and freedom have begun to regerminate in the minds and hearts of the younger generation." (Shuyuan Lu in The Ecological Era and Classical Chinese Naturalism). Some of these young Chinese move to the countryside, to eco-villages. Of course they do not find the move easy. Some stay in a village for a few days or a week; some stay for years. But their aim is to recover felt bonds with nature and gain freedom from what Professor Lu calls "the cage" of industrial civilization, wherein the air is not clean and the soul itself is polluted with greed, hatred, and confusion. They want to farm, to "chant in the fields," to reclaim a spontaneous earth-based way of living. Karen, a resident of the Sunshine Eco-Village outside Hanzhou, is an example. A lover of Chinese traditions, I met her in the Sunshine Eco-Village near Jiande, China, in the summer of 2018. In the spirit of Taoism, she shared some wine with me and others. She was proud of the villagers and their wisdom and wanted to learn from them. I wanted to learn from them, too. As an American college teacher, I, too, am in a cage of sorts: the cage of anthropocentrism, they cage of hurriedness and compulsion, the cage of a self-centeredness that measures life in terms of appearance, affluence, and marketable achievement, the cage of consumer culture. Yes, I, too, would like to find another and better way: a way that is aware of the bright but cleaves to the dark: thhe womb-like font from which all creativity comes. And love, too. The womb of Creative Compassion. |

7. The Way of Creative Compassion:

Process Thinking in China

|

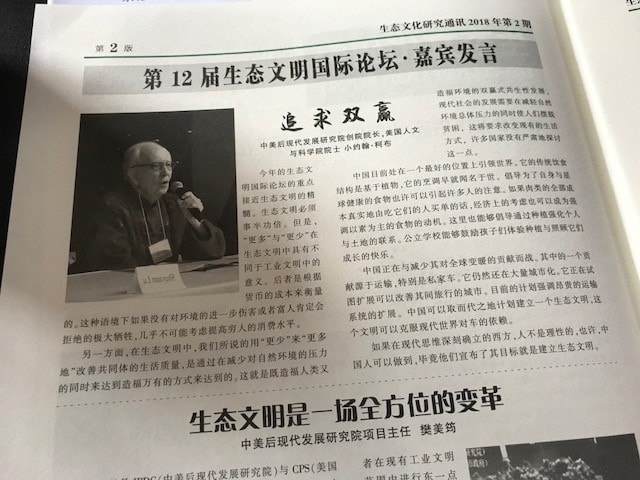

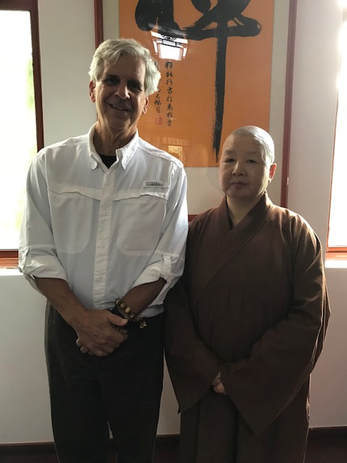

Why I Go to China

by Jay McDaniel I go to China most every summer to make friends, and to give talks and lead workshops on process thinking or process thought. Maybe you haven't heard of process thought? In the section below I will say more about that I mean by process thought in a short five sentences, in both Chinese and English. I do this at the request of some Chinese friends of mine. But first, some context. In China Process Thinking is not simply a philosophy; it is also, and perhaps more deeply, a way of living. I call it "the way of Creative Compassion." When I do to China i encourage my Chinese friends to explore this Way from out of their own resources. I explore them myself, in companionship with them. We are seeking wisdom together in a spirit of cross-cultural friendship. My work is sponsored by the Institute for the Postmodern Development of China. Dr. Zhihe Wang and Dr. Meijun Fan, founders of the Institute, make all of this possible. Creative Compassion I arrived at the simple phrase Creative Compassion in response to a question from Karen, who is pictured at the top of this page. She was a resident of the Sunshine Village Eco-Village just outside Hangzhou. There is a growing network of eco-villages in China, and our summer academy was at one of them. Karen asked me to articulate the meaning of process thinking in one word, but I needed two. 'Creative Compassion," I said. As I see it, the Way of Creative Compassion can include many ways. It an be practiced by Buddhists, Christians, Daoists, Hindus, Jews, Muslims and the countless people around the world who are "spiritually interested but not religiously affiliated." The majority of Chinese are in the latter category. The Way is compassionate in that its bond of empathy include strangers as well as friends and family, the more-than-human world as well as human beings. And it is creative because it unfolds moment-by-moment in a spirit of improvisation: open to the call of the moment and to the fresh possibilities for living that come with it. Always it is discovering something new. Always it is on the road even if settled in one place. It is also a Way that Knows the Bright while Cleaving to the Dark, I will explain this phrase in the final section on the poet Tao Yuanming, as introduced to me by Professor Shuyuan Lue. Why "Process"Thinking? The Way of Creative Compassion - a Way that Knows the Bright while Cleaving to the Dark - is being explored by Chinese in many different settings, both rural and urban, under the banner of process thought or process thinking. The question naturally emerges, Why call it "process" thinking? The word "process" is meant to indicate the that the Way is itself a process. It partakes of what the Chinese call Tong: 通. Here is how Dr. Zhihe Wang and Dr. Meijun Fan explaing Tong. In the Chinese language, Tong(通)is a very widely used word. Structurally, it is composed of two parts: one is “walk,” one is “road.” The original meaning of Tong as a verb means: open, penetrate, get through, remove obstacles, unimpede, connect, communicate, link up, etc. As an adjective, Tong refers to whole, all, general, holistic, comprehensive, etc. Therefore, “Tong” is inherently related to Dao or Tao (the Way). In the words of Zhuangzi or Chuang-tzu (c. 369 BCE – c. 286 BCE), a defining figure in Chinese Taoism, “Dao identifies itself with Tong.”[1]Tong is not only the “the original meaning of Dao,” but also “the fundamental feature and condition of Dao”, because a way cannot be called a way if it is not open. The Way of Creative Compassion is indeed "on the way" in the spirit of Tong. I go to China to explore it and, I hope, embody a bit of it in my own life while others do the same.

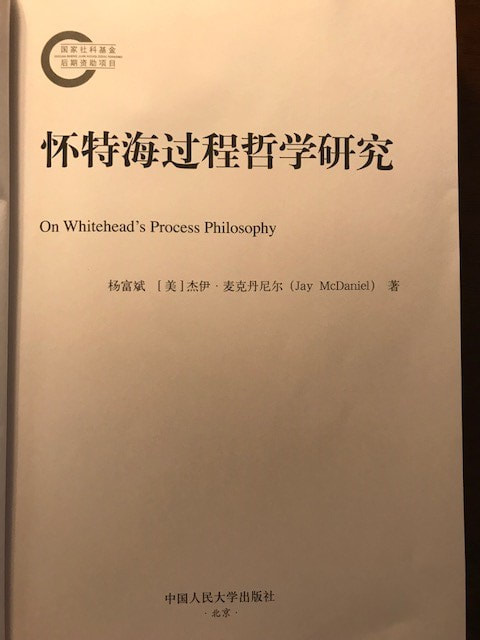

The Philosophy of Whitehead In exploring the Way most of my Chinese friends draw from the wisdom of traditional Chinese sources: Daoism, Confucianism, Buddhism, traditional Chinese medicine, and the arts. They are reclaiming the cultural treasures of their own Chinese past, which were neglected and sometimes repressed in the 20th century. They also draw from the philosophy of Alfred North Whitehead. Whitehead's philosophy functions as a bridge between East and West and a bridge toward the future. A bridge toward the way of creative compassion. The way of Creative Compassion is personally satisfying to those who practice it. It partakes of all the subjective moods (37 of them) that form a spiritual alphabet for human lifeL They find happiness and a certain kind of inner peace in walking its paths. But the Way also has a social aim. It is to help build Ecological Civilizations. An ecological civilization is easy to imagine and hard to realize. It is a nation -- a culture -- consisting of communities that are creative, compassionate, participatory, culturally diverse, humane to animals, ecologically wise, and spiritually satisfying – with no one left behind. The citizens live of these nations live with respect and care for the community of life and one another. They listen to one another and feel listened to, knowing that every voice counts. They belong to, and help create, what scholars have come to call a nurturing society. A nurturing society is a society oriented toward nurturance rather than domination, mutual support rather than hyper-competition, persuasion rather than coercion. Its citizens understand themselves as individuals, but they do not fall into a cult of individualism. They are faithful to the bonds of relationship: relationships with friends and family, to be sure, but also to neighbors and strangers, and of course to the natural world as well. The hills and rivers, the trees and stars – they, too, are their friends. They are what Zhihe Wang and Meijun Fan call eco-persons; they possess what process philosophers call wide souls. Their approach to life helps build and sustain nurturing societies -- the kind of society encouraged by constructive postmodern thinkers around the world, including those in China. I go to China because I believe in the Way of Creative Compassion and in the goal of Ecological Civilization. When I go, I lead workshops or give talks on Whitehead's philosophy, but I simultaneously discover that Whiteheadian ways of thinking have been part of China long before Whitehead was born. I myself have co-authored a book, in Chinese only, with Dr. Fubin Yang called On Whitehead's Process Philosophy (2018). The true pioneers of thinking about the Way of Creative Compassion in a Chinese context are Dr. Zhihe Wang, Dr. Meijun Fan, and Dr. John Cobb. |

Professor John Cobb in ChinaDr. Zhihe Wang and

|

8. Eight Lessons to Learn from Tao Yuanming

"Tao Yuanming spent most of his life in reclusion, living in a small house in the countryside, reading, drinking wine, receiving the occasional guest, and writing poems in which he often reflected on the pleasures and difficulties of life in the countryside, as well as his decision to withdraw from civil service. His simple, direct, and unmannered style was at odds with the norms for literary writing in his time." (Wikipedia)

|

The first lesson to learn from Tao Yuanming is to know the bright but cleave to the dark. a phrase which appears in Chapter 28 of the Lao Tzu's Dao de Jing.

From a process perspective "to know the bright but cleave to the dark" is to center your life in something that is mysterious, beautiful, the mother of all creation, present throughout creation, and that cannot be encased by the grasping mind. We speak of this dark as the lure to healing and wholeness. It is within each person and also beyond each person. Here "the bright" represents all that glitters in our world, in ways healthy and unhealthy. The bright includes the hills and rivers and also the displays in department stores by which people feel lured to measure their lives in terms of the conspicuous consumption. It is, as it were, the yang side of life. Within yet beyond the bright is something more intuitive and nourishing, and which can only be felt once the grasping mind is relinquished. We can call it the Dao, understood as the Way of the Universe. Or, more poetically, we might all it the Dark. Professor Lu introduces seven more ideas which resonate deeply with my own process perspective. One of them is the theme of Abandonment, Aloofness, and Serenity, At first glance this might seem insufficiently relational for a process perspective, but on second thought it seems just right. We process thinkers recognize that we need to abandon and remain aloof from the false values of consumer culture: namely, appearance, affluence, and marketable achievement as measurements of life's well-being. We realize to the contrary that, whether we live in the city or the countryside we need to find a place within ourselves where there is a sense of balance: a serene heart. Only with this serenity can we add beauty to the world.

A third theme is Returning to Nature. Here the connections with Process Philosophy are obvious. Process philosophy is a cosmological tradition which sees human life as within, not outside of, the larger web of life. In truth, we do not need to return to nature, we need to recognize that we are always already within the larger horizons of nature, understood as the web of life. We need to return to what we have always known, but forgotten. A fourth theme is honest poverty. The poverty at issue is not that of hunger and disease. It is that of living simply, with enough to enjoy modest comforts of life, but not with more. Process philosophy reminds us that there is enough in the world for everyone's needs, but not everyone's greeds. The witness of Tao Yuanming reminds us of the same. A fifth theme is the importance of Ease and Idling. Professor Lu is right. Contemporary culture places too much emphasis on work, on labor, at the expense of simultaneously recognizing the human need for play and wonderment. There is a need for idle time, a need to end a day by "doing nothing" that pertains to the marketplace: spending time with friends and family, enjoying music and the arts, playing games, having fun. industrial society an lose the importance of play in human life; Tao Yuanming invites us to return to play. A sixth theme is that of Peach Blossom Springs, understood as a place in the heart if not also geographically, where people truly live in harmony with the earth and one another. This theme functions as an ideal to be approximated: that of dwelling poetically on the Earth, as Professor Lu explains. It is akin to what Martin Luther King, Jr. called Beloved Community, with ecology added. A seventh them is the Cage. Professor Lu rightly reminds us that we live in cages both mental and physical. The mental cages are the most serious. They are the mechanistic ways of thinking that cut us off from one another and the rest of the world by rendering the world itself into a mere collection of objects (in reserve for our use) rather than a communion of subjects (present to us as subjects of respect and love. The poetry of Tao Yuanming is an invitation to gain freedom from the Cage. An eighth and final theme is the idea that Tao Yuanming can indeed be resurrected. He is, in the language of Derrida, a spectre in the imagination: a spectre who comes from the future and not simply the past. His body consists, not only of his writing, but more deeply of his spirit, his ideas, his hopes. One aim of Process Philosophy is to help resurrect ideas such as he proposes: cleaving to the dark while knowing the light. It is from the dark itself, from the uncontainable womb of creative compassion, that hope comes tomorrow and perhaps also, we might hope, today. |

“Knowing the bright but cleaving to the dark” appears in Lao Tzu (Chapter 28). Arthur Waley’s translation of the chapter is as follows: |

Addendum: Powerpoints for Use in Introducing Process Thinking

| Ecological Civilization and Whole Person Education: A PPT on Process Thinking for Chinese Readers |

| Collecting Light: A PPT on Process Thinking for Chinese Readers |

| Ecological Civilization and Whole Person Education (In Chinese) |