Football: It's About the Hitting

John Churchill, PhD

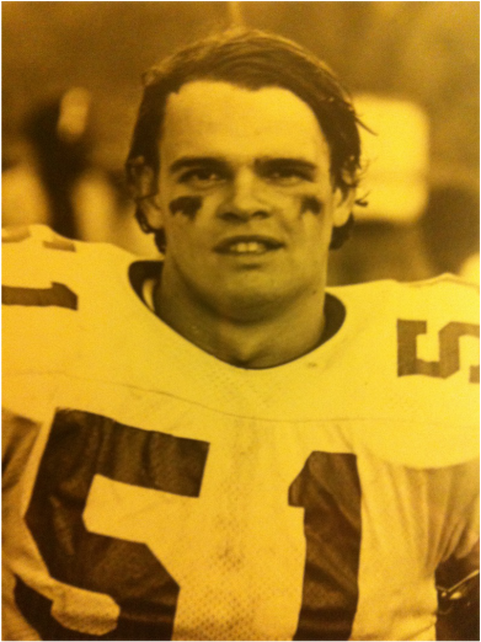

John Churchill after a game in which Southwestern beat Washington and Lee, 42-14.

Overlay of Remembrance

The grass had that sweet, intense, wet, green smell, as if freshly cut--the smell that gives us such a rush of well-being. I could feel it against my cheek. I lifted my chin and saw the scoreboard, with the time left to play ticking away, second by second, in white lights, and each team's points given in yellow ones under signs that said "visitors," and some team name--Wildcats, or Panthers. I was in the midst of an enclosed capsule of light, the evening darkness sealing it all around. Closer in there were moving legs and shoes, the sturdy, lace-up football shoes called "cleats." I lay there in the unshakeable certainty that I had seen and done and experienced all this before. Not something like this pretty much, but just exactly this very thing. It was déjà vu.

That night convinced me of something about the experience called déjà vu, the common experience we sometimes have when a scene we know is novel in our lives presents itself with an irresistible overlay of remembrance. I have this sense infrequently, but when it comes--walking into a room we've never visited, meeting someone for the first time, looking at a vista down a city street--there is no disputing the impression: "I've seen this before!" Some people take this an evidence of remembering past lives. Not me. I had just made a good tackle, bringing down the ball-carrier, and in the process had taken a sharp blow to the head. As one of my coaches used to say, I had "scrambled my brains." Déjà vu.

Vividness of Immediate Experience

Sometimes people like to talk about football in ways meant to redeem its violence, and give some sort of justifying, positive moral slant to this business of crashing around into other people and throwing them to the ground. They often talk about a predictable set of lessons. They talk about learning to work hard and sacrifice in order to achieve goals, about teamwork, learning to get your job done because others depend on you, learning to depend on others, overcoming fear, continuing on through pain and injury, hanging in there when things are tough, never giving up, and so on. I think all that is probably right, or can be, though I also don't doubt that there are negatively skewed versions of all these moral lessons, and that football could teach stupid stubbornness as well as resolute determination, or vindictiveness as well as fair play. It depends.

But I am sure that one thing I owe to football, and almost certainly to its violence, is a particular keen awareness of the vividness of immediate experience. I had a buddy in college who used to listen to Tchaikovsky's 1812 Overture before games. It builds to a crashingly triumphant finale, with the old Russian national anthem exploding into peels of church bells and cannon fire. After that he was ready to go out and hit. I watched him with envy before games. He seemed so ready, and I was so full of dread. I would sit in the locker room and listen to the coaches trying to whip up our emotion, morosely analyzing their rhetorical ploys, thinking about what they were trying to do to us, emotionally, rather than responding to it. And so I took the field almost reluctantly, with the thought, "Why am I here? What on earth is going on and why did I agree to it?"

Withness of the Body

Then with the kick off I would take a hit. It took that first blow, the impact. Oh, yeah, then I knew why I had come and why I had prepared and practiced all those weeks. After the first blow, I was ready. And I loved it. I loved hitting. Once, interviewing for a prestigious scholarship, I was asked by a committee member what I liked about football. Who knows where my answer came from? But it was swift and unpremeditated. "In football," I said, "you get to use your entire body as a striking instrument." I'm still convinced that that's it, the appeal and inexpungeability of the game. It's really a very old game. There is a reference to football players in Shakespeare's King Lear(not complimentary), and English kings of the middle ages repeatedly tried to stamp it out. Their hostility was based partly on its intrinsic violence and its proneness to lead to civil disorder, and partly on the conviction that it distracted young men from the practice of archery, essential to the defense of the realm. I think its enduring appeal, and the reason it will always be very hard to regulate, tame it, and make it safer lies in the totalizing experience of committing your entire body to striking something. OK, striking someone.

I'm not saying this is a good thing. I'm saying that it's a powerful experience. You're all-in. The impossibility of leaving anything in reserve--or maybe I ought to say the extreme inadvisability of leaving anything in reserve, unless you want to get run over--creates a kind of heightened consciousness. By God, it's happening! People who write about the extreme experience of combat, or of having been in absolutely terrifying danger, testify to an experience of heightened reality. I would not for a moment trivialize such genuinely momentous real life experiences with comparisons to a mere game, but it may be that what games like football can give us is a more or less controlled setting where something like that sense of immediacy can be tasted.

A Fact is There!

If something like that is right, then there are things to learn. About the texture of time and the sequentiality of events, for example. Football, in my experience, has given me moments when--somehow, suddenly, almost without lead-in--a fact is there! I recall intercepting a pass in a game against the Coast Guard Academy. There it was. I had the ball! Here I mean to illustrate the sharp, timeless focus on What Is Now the Case. I have the ball. There is no thought of how I came to have it, what I will do with it, whether I ever held it before. Just the sheer power of the fact itself of the ball in my hands. Timeless.

Or the feeling of the impending next thing. I recall lying on the sidelines, exhausted, late in a game in which we already trailed by an absurd score. We ultimately lost 62-8. (You lose by that score in the following way: You're down 62-0, get a last minute touchdown for 6, and take the risk of going for 2 points on conversion. Whatever.) Anyway, it might have been 55-0, and I was lying, panting on the sidelines while our team tried with futility to move the ball. As I lay there, I knew I would be go going back into the game at any moment, when we fumbled the ball away, to play defense. What I remember is the sweetness of the relaxation, edged with the certainty of its interruption. Not timelessness at all: a vivid sense of the time-bound nature of our lives.

Any old football player could go on forever like this. We remember particular plays, particular tackles, particular moments of diving for the ball as it lolled in the grass indifferent to our passion for possessing it. The point, though, is not merely to recall such intensity, but to have awakened to the possibility of experience on that level, and to be able to carry that receptivity into the rest of life. I am convinced that much of whatever ability I have to savor the sheer flavor of life is rooted in the capacities I gained in the intense experiences of football, and that I owe them to football just as much as the pain I feel every morning in my knees.

The grass had that sweet, intense, wet, green smell, as if freshly cut--the smell that gives us such a rush of well-being. I could feel it against my cheek. I lifted my chin and saw the scoreboard, with the time left to play ticking away, second by second, in white lights, and each team's points given in yellow ones under signs that said "visitors," and some team name--Wildcats, or Panthers. I was in the midst of an enclosed capsule of light, the evening darkness sealing it all around. Closer in there were moving legs and shoes, the sturdy, lace-up football shoes called "cleats." I lay there in the unshakeable certainty that I had seen and done and experienced all this before. Not something like this pretty much, but just exactly this very thing. It was déjà vu.

That night convinced me of something about the experience called déjà vu, the common experience we sometimes have when a scene we know is novel in our lives presents itself with an irresistible overlay of remembrance. I have this sense infrequently, but when it comes--walking into a room we've never visited, meeting someone for the first time, looking at a vista down a city street--there is no disputing the impression: "I've seen this before!" Some people take this an evidence of remembering past lives. Not me. I had just made a good tackle, bringing down the ball-carrier, and in the process had taken a sharp blow to the head. As one of my coaches used to say, I had "scrambled my brains." Déjà vu.

Vividness of Immediate Experience

Sometimes people like to talk about football in ways meant to redeem its violence, and give some sort of justifying, positive moral slant to this business of crashing around into other people and throwing them to the ground. They often talk about a predictable set of lessons. They talk about learning to work hard and sacrifice in order to achieve goals, about teamwork, learning to get your job done because others depend on you, learning to depend on others, overcoming fear, continuing on through pain and injury, hanging in there when things are tough, never giving up, and so on. I think all that is probably right, or can be, though I also don't doubt that there are negatively skewed versions of all these moral lessons, and that football could teach stupid stubbornness as well as resolute determination, or vindictiveness as well as fair play. It depends.

But I am sure that one thing I owe to football, and almost certainly to its violence, is a particular keen awareness of the vividness of immediate experience. I had a buddy in college who used to listen to Tchaikovsky's 1812 Overture before games. It builds to a crashingly triumphant finale, with the old Russian national anthem exploding into peels of church bells and cannon fire. After that he was ready to go out and hit. I watched him with envy before games. He seemed so ready, and I was so full of dread. I would sit in the locker room and listen to the coaches trying to whip up our emotion, morosely analyzing their rhetorical ploys, thinking about what they were trying to do to us, emotionally, rather than responding to it. And so I took the field almost reluctantly, with the thought, "Why am I here? What on earth is going on and why did I agree to it?"

Withness of the Body

Then with the kick off I would take a hit. It took that first blow, the impact. Oh, yeah, then I knew why I had come and why I had prepared and practiced all those weeks. After the first blow, I was ready. And I loved it. I loved hitting. Once, interviewing for a prestigious scholarship, I was asked by a committee member what I liked about football. Who knows where my answer came from? But it was swift and unpremeditated. "In football," I said, "you get to use your entire body as a striking instrument." I'm still convinced that that's it, the appeal and inexpungeability of the game. It's really a very old game. There is a reference to football players in Shakespeare's King Lear(not complimentary), and English kings of the middle ages repeatedly tried to stamp it out. Their hostility was based partly on its intrinsic violence and its proneness to lead to civil disorder, and partly on the conviction that it distracted young men from the practice of archery, essential to the defense of the realm. I think its enduring appeal, and the reason it will always be very hard to regulate, tame it, and make it safer lies in the totalizing experience of committing your entire body to striking something. OK, striking someone.

I'm not saying this is a good thing. I'm saying that it's a powerful experience. You're all-in. The impossibility of leaving anything in reserve--or maybe I ought to say the extreme inadvisability of leaving anything in reserve, unless you want to get run over--creates a kind of heightened consciousness. By God, it's happening! People who write about the extreme experience of combat, or of having been in absolutely terrifying danger, testify to an experience of heightened reality. I would not for a moment trivialize such genuinely momentous real life experiences with comparisons to a mere game, but it may be that what games like football can give us is a more or less controlled setting where something like that sense of immediacy can be tasted.

A Fact is There!

If something like that is right, then there are things to learn. About the texture of time and the sequentiality of events, for example. Football, in my experience, has given me moments when--somehow, suddenly, almost without lead-in--a fact is there! I recall intercepting a pass in a game against the Coast Guard Academy. There it was. I had the ball! Here I mean to illustrate the sharp, timeless focus on What Is Now the Case. I have the ball. There is no thought of how I came to have it, what I will do with it, whether I ever held it before. Just the sheer power of the fact itself of the ball in my hands. Timeless.

Or the feeling of the impending next thing. I recall lying on the sidelines, exhausted, late in a game in which we already trailed by an absurd score. We ultimately lost 62-8. (You lose by that score in the following way: You're down 62-0, get a last minute touchdown for 6, and take the risk of going for 2 points on conversion. Whatever.) Anyway, it might have been 55-0, and I was lying, panting on the sidelines while our team tried with futility to move the ball. As I lay there, I knew I would be go going back into the game at any moment, when we fumbled the ball away, to play defense. What I remember is the sweetness of the relaxation, edged with the certainty of its interruption. Not timelessness at all: a vivid sense of the time-bound nature of our lives.

Any old football player could go on forever like this. We remember particular plays, particular tackles, particular moments of diving for the ball as it lolled in the grass indifferent to our passion for possessing it. The point, though, is not merely to recall such intensity, but to have awakened to the possibility of experience on that level, and to be able to carry that receptivity into the rest of life. I am convinced that much of whatever ability I have to savor the sheer flavor of life is rooted in the capacities I gained in the intense experiences of football, and that I owe them to football just as much as the pain I feel every morning in my knees.