- Home

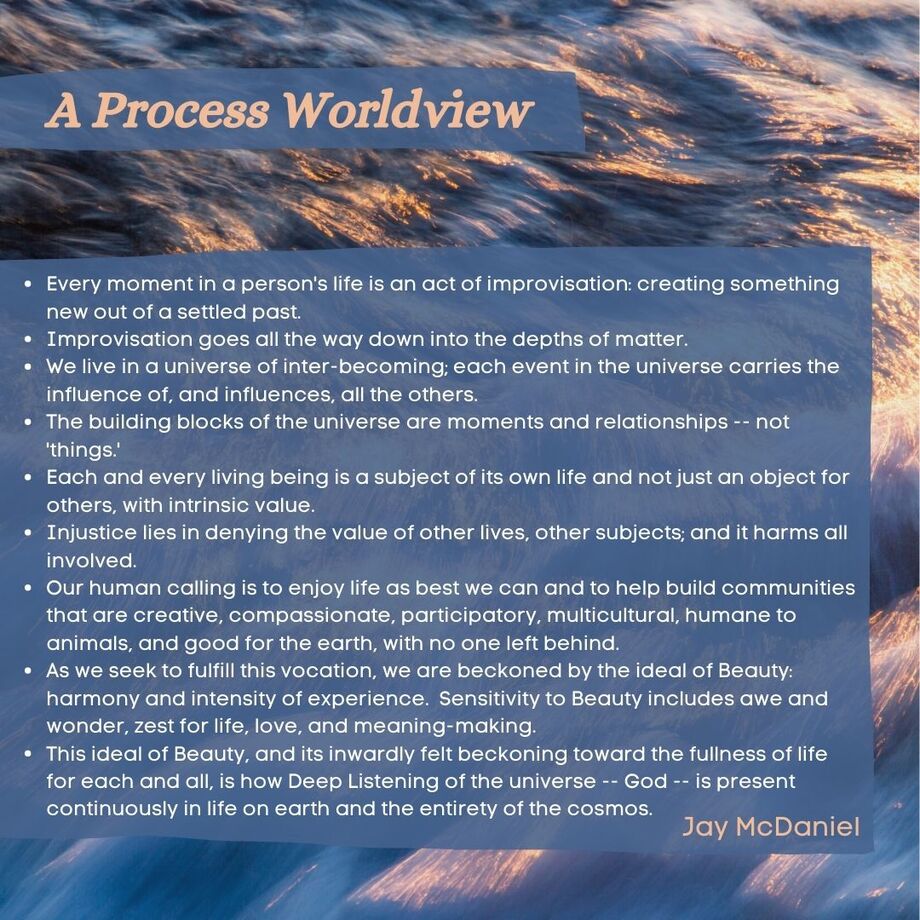

- Process Worldview

- Community

- Art and Music

- Whitehead and Process Thinking

- Podcasts

- Spirituality

- Ecological Civilization

- Education

- Contact

- Social Justice

- Science

- Animals

- Sacred Poems

- Whitehead Videos

- Index of All Titles

- Practicing Process Thought

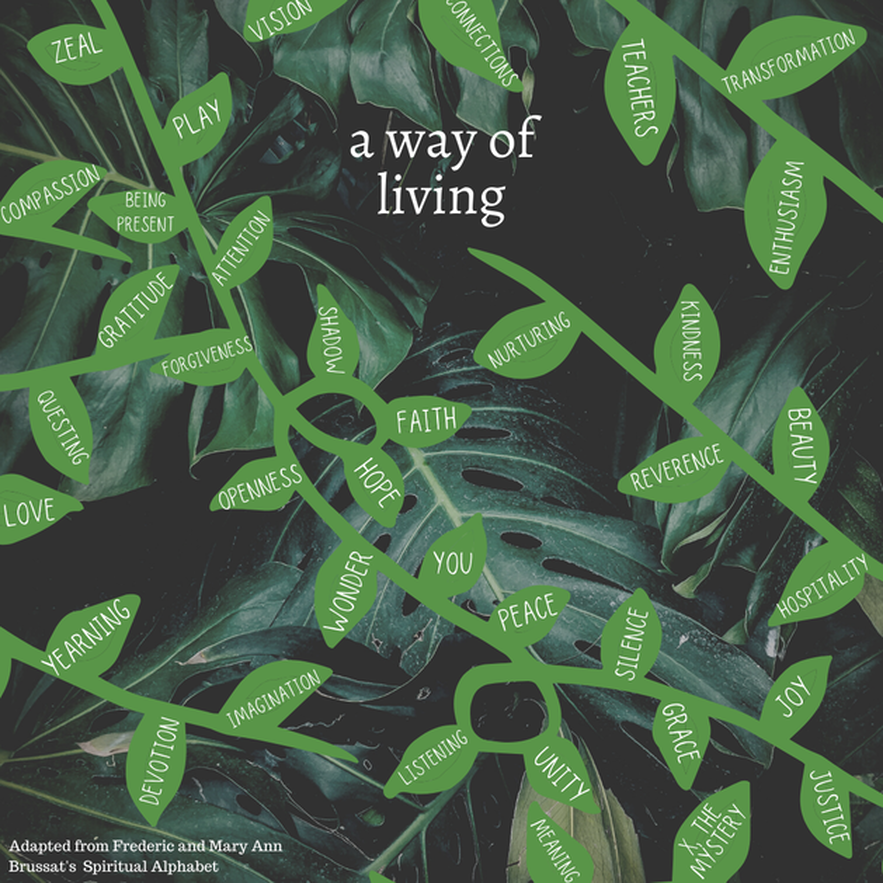

- Process Spirituality: A Spiritual Alphabet

- Recent Posts

The Process movement is a network of people around the world who want to make a constructive difference in the world. They include farmers, artists, business persons, government officials, philosophers, sociologists, educators, grandmothers, social workers, musicians, and poets. Some are religious and some are not; but all are hopeful.

Those who are religious include Bahais, Buddhists, Christians, Daoists, Hindus, Jews, Muslims, Pagans, and Unitarian Universalists. These traditions are very important to them, and they weave a process outlook on life onto, and with help from, their spiritual lineages.

Nevertheless some people in the process network are spiritually interested but not religiously affiliated. Indeed, for many, including those who enjoy a sense of religious belonging, the topic of "religion" is not as important to them as are many other topics facing humanity, other animals, local communities, and the Earth today.

So what do they have in common? They share four hopes that animate their actions in local communities and the broader world.

Whole Persons. They work to help individuals around the world grow in personal wholeness and spiritual vitality (e.g. creativity, beauty, love, forgiveness, faith, playfulness, gratitude, listening, and a sense of wonder)

Compassionate Communities: They help build compassionate communities that are creative, caring, participatory, diverse, inclusive, good for animals and good for the Earth: with no one left behind.

A Flourishing Planet: They work to help the planet as a whole flourish with its many forms of life. Toward this end they encourage "world loyalty" as well as "local loyalty," encouraging people to think of the Earth as a whole as an Earth Community deserving respect and care. This hope lies behind their commitment to "ecological civilizations."

Holistic Thinking. They encourage holistic ways of thinking - drawing from science, art, philosophy, and spirituality - that help people live with respect and care for the Earth community, enjoy meaningful bonds in local settings, and find personal happiness.

For process thinkers there are many obstacles to these hopes. Examples include (1) the excessive individualism of western modernity and consumer culture, (2) a mechanistic understanding of the world that reduces all things to inert objects in space, (3) the failure of higher education to address serious problems of the world, and (4) the failure of education as a whole to help people become whole persons in whole communities.

Some process thinkers believe that the world is headed toward catastrophe: global climate change, chronic economic inequities, animosities between nations, and political dysfunction, The four hopes are not just icing on a cake. They are necessary for survival.

Many process thinkers take the philosophy of the late mathematician and philosopher, Alfred North Whitehead, as an alternative to hyper-individualism and mechanism and believe that his "philosophy of organism" is the kind of holistic thinking sorely needed. Below I offer an example of a Whiteheadian version of holistic thinking.

Some process thinkers believe that the world is headed toward catastrophe: global climate change, chronic economic inequities, animosities between nations, and political dysfunction, The four hopes are not just icing on a cake. They are necessary for survival.

Many process thinkers take the philosophy of the late mathematician and philosopher, Alfred North Whitehead, as an alternative to hyper-individualism and mechanism and believe that his "philosophy of organism" is the kind of holistic thinking sorely needed. Below I offer an example of a Whiteheadian version of holistic thinking.

Those of us in the Process movement recognize and celebrate that there are other, non-Whiteheadian forms of holistic thinking that are also condusive to living with respect and care for the community of life on Earth. The Process network can well include Islamic, Jewish, East Asian, African, and Ingenous forms of wisdom that are Whiteheadian, but that are extremely important if the four hopes are to be realized. It is the four hopes that matter the most. They are what animate the Process movement.

- Jay McDaniel, July 7, 2021

Addenda

What Would Whitehead Think?

10 Principles of Whiteheadian Thinking by John Cobb

1. Question the assumptions of your community, your society, your religion, your science, your educational institutions, especially those that are rarely mentioned.

2. Question the dominant media, asking who controls it and what they want you to think.

3. Recognize that a serious answer to any important question brings into view lots of other questions.

4. When people appeal to mystery, consider that it may be mystification. Push critical thought as far as you can.

5. Recognize that the wider the range of influences on an event or person that you consider, the better you understand that event of person.

6. Recognize that the broader your consideration of the context and of the likely consequences of your action, the better the chance that you will make the right choice.

7. Realize that all your ideas and values are influenced by your particular situation, but refuse to conclude that for this reason they can be dismissed as merely “relative.”

8. Recognize that there may be no actions that are completely harmless, but do not let that prevent you from acting decisively.

9. Understand that compassion is the most basic aspect of our experience, and seek to liberate and extend your compassion to all with which you come in contact.

10. Deepen your commitments to your own immediate communities, but always remember that other communities make similar demands on their members. Let your ultimate commitment be all-inclusive.

Practicing Process Thought

in Local Settings

Some Guidelines

Think big, but think small, too. Always listen. Let God be in heaven as well as on earth. Avoid cliches and jargon. Remember the cosmic but honor the particular. Seek unity but be a champion of differences. Avoid self-absorbed mysticism. Learn from science and beauty. Love your enemies. Don't hide from the brokenness. Make merry when you can. Be kind.

A new process organization is emerging by the name of The Cobb Institute: A Community for Process and Practice. Click here to visit their website. As I told a former student about the Cobb Institute, he asked me what it really means to practice the process way. I thought of so many activities: being kind, building compassionate communities, spending time in nature, praying and meditating, being curious, gathering in community, spending time alone, studying and learning (including studying process thought), creating and enjoying music and art, resisting evil, loving your enemies, and wholesale (sometimes raucous) merry-making. I emphasized that an important part of the practice is social and prophetic. It is to help create ecological civilizations, the fundamental units of which are local communities, in rural and urban settings, that are creative, compassionate, participatory, inclusive, good for animals, and good for the earth, with no one left behind.

I added that, at a local level, the practice of process thought has a lot to do with practicing the art of living and pointed him toward this statement developed by the Cobb Institute on spiritual integration. It defines spirituality as embodied wisdom and emotional intelligence in daily life. He also wanted some more general guidelines, so I came up with the list that you will find below. The guidelines I offer aren't rigid or final, and I don't speak for the Cobb Institute. Its many friends might arrive at a very different list of suggested guidelines. Let them be springboards for your own reflection.

I added that, at a local level, the practice of process thought has a lot to do with practicing the art of living and pointed him toward this statement developed by the Cobb Institute on spiritual integration. It defines spirituality as embodied wisdom and emotional intelligence in daily life. He also wanted some more general guidelines, so I came up with the list that you will find below. The guidelines I offer aren't rigid or final, and I don't speak for the Cobb Institute. Its many friends might arrive at a very different list of suggested guidelines. Let them be springboards for your own reflection.

Be there, be here

Be there with the whole of it as best you can. With people in other parts of the world, with the hills and rivers, trees and stars. Grieve with them and hope with them. Have planetary feeling. Know that the universe is a communion of subjects and not simply a collection of objects. See something like subjectivity, vital energy, everywhere. Fall in love with the all.

And also be here with your local community, with friends and family, neighbors and strangers close at hand. Don't pretend that you are, or need to be, everywhere. Help your local community become creative, compassionate, participatory, diverse, inclusive, humane to animals, and good for the earth, with no one left behind. Help people in your community know, and be compassionately linked with, people in other communities. Help them understand that we are small but included in the larger web of life. Help them love the local and love the planetary. Call it ecological civilization.

Always listen

Especially if you are in a position of privilege, make sure you listen to other people and also to the more than human world. Let the voices of others enter your ear, let the experiences of others be part of your life. Feel their feelings as best you can, without pretending that they are your own. Don't just listen to what you like; listen to what irritates you, or shocks you, or changes you.

Also listen to your body, to your own feelings, and, as you can, listen for a still small voice inside you which is God's calling. Know that even God begins with listening: with feeling the feelings of all things and responding with fresh possibilities. Listen for the fresh possibilities.

Think small as well as big

We're all familiar with the axiom "think globally, act locally." It's a good one. But it's important to think locally, too. Think small as well as big. Don't pretend that global consciousness is superior to local consciousness, or the other way around. Let the two forms of consciousness be on a par, on the same level. See beauty in those who think locally and encourage them to think globally. And see beauty in those who think globally and encourage them to think locally.

Critique all notions of global thinking that somehow neglect the fact that other creatures matter, too, that the "globe" is not a human globe. And critique all notions of global thinking that neglect just how differentiated and fragmented the world is, ecologically and humanly. Avoid saying "we're all in this together" if there's even a hint that "we" are - or should be - one big, happy, middle class, western family. Be honest about the fragmentation, the brokenness, the injustice.

Seek harmony and unity, but be a champion of differences

It's good to want people and other living beings to dwell in mutually enhancing harmonies. It's good to talk about peace and unity. But also be a champion of differences: different religions, different cultures, different personalities, different animals, different seasons, different landscapes, different moods. Don't fall into the trap of sameness, of presuming that there is one "right" way to be human or to be alive or to exist. Don't let your convictions and views and values become an umbrella that suffocates others. Be glad that there are people who disagree with you. Be glad that not everyone is a process theologian.

Avoid self-absorbed mysticism

It's good to have a mystical side: a sense of the numinous, a feeling of oneness, a love of beauty, a capacity for silence, a heart for the ecstatic. But don't fall into the trap of saying it's all here. Accept the fact that your here is different from the here of someone in another country, a distant city, another zip code, another social class, another race, another religion. Even next door. Give other people space to have their own here: to have feelings and wisdom and beauty that are not your own. Don't pretend that you are disembodied; that your here is everywhere. Let there be many here's, some of which are there for you. Know that being there means honoring the distance and uniqueness of what is here for others.

Remember the cosmic but honor the particular

Remember the cosmic. Don't think that human beings on planet earth are the center of creation. We are small but included in an evolving galactic whole. But also remember that the whole of the universe is contained in each particular, in each grain of sand, and that the individual grains are where the action is.

Know that "everything is interconnected" but also that connections are always unique and specific. Your connections with your parents are different from your connections with best friends, which are different from your connections with small children, which are different from your connections with trees and soil and sunshine. Have affection for the particular, for the small, for the unique, for the specific. Avoid the fallacy of misplaced concreteness.

Avoid cliches and jargon

In explaining process thought to others, or to yourself, avoid cliches to the best of your ability, such as "everything is interconnected" and "the future is open." They grow tiresome and empty. Seek out poets and find fresh ways to say things. Use specific and poetic language when possible, and don't be afraid to appeal to intuition. Remember that, for Whitehead, ideas can be expressed in many different ways and are not reducible to words. They can be expressed through illustrations as well as abstractions. Have a little Zen in you; in explaining how everything is interconnected, offer someone a cup of tea.

Avoid process jargon to the best of your ability. Use only when necessary. It's alright to say "actual entities" every once in a while, but also just say moments of experience. It's alright to say "eternal objects" every once in a while, but also just say the pure potentials. It's alright to say "the consequent nature of God," but also just say God's tenderness or the deep Listening. It's alright to speak of "creative transformation," but also say, with Gerard Manley Hopkins, the freshness deep down. Don't fall into what Whitehead calls the fallacy of the perfect dictionary. Create your own dictionary.

Learn from science and beauty

Remember that for Whitehead the objects in our world are facts, as are our subjective responses to those objects. Science does an excellent job of helping us understand the objects of our world, especially if science is liberated from mechanistic paradigms that forget the qualitative and organic sides of the world. Be willing to critique the mechanism but also learn from the insights. Appreciate the fact that science is evidence-based and try to be evidence based yourself, albeit with an expanded understanding of evidence that includes beauty.

Beauty is the richness of experience found in human life and the more than human world: the harmonies and intensities, sometimes pleasurable and sometimes painful, that are life as lived from the inside. The arts (music, literature, poetry, dance, sculpture, drama) are masters of presenting beauty. And so, in a different but complementary way, are the hills and rivers, trees and lakes, planets and stars. The awe we feel in the presence of a mountain or ocean tell us something about the world no less than a scientific accounts of those immensities. The truths we discern from a really good movie about life on a battlefield are no less valuable than the facts and figures about that battle. A song or dance well performed, that tells us about the cruelties of injustice is as informative, if not more informative, than a more prosaic account of those cruelties. Know that facts include the subjective as well as the objective: in Whitehead's words, the private matters of fact and the public matters of face. Stick to the facts and learn from them all.

Let God be in heaven and on earth.

If you believe in a personal God who has properties such as love and wisdom, and who prefers peace over violence, justice over hatred, let God be there, too. There in your nearby neighbors, there in people in other parts of the world, there in plants and animals. Acknowledge that their ways of knowing God may be very different from your own, and beautiful, too. Be responsible to the face of the other (Levinas). Love their there-ness.

Also, don't talk about divine immanence all the time. Let God have a here of God's own, which is other to your own here. Just as other people transcend you in their uniqueness, and other animals and plants do the same, so let God transcend you. Speak of God as the Deep There. Address God as You who transcends and loves you and you and you.

Celebrate local connections and enjoy life.

Know that life is more than ethics, more than "being good." It's also about gladness and playfulness, wonder and a sense of mystery. About friends and family, music and storytelling. About food and water, bicycles and trees. About laughter and struggle, silence and beauty. Let your here include zest for life. Let it include all the "letters" in the spiritual alphabet: Use your time, energy, and money to help others do the same.

Be there with the whole of it as best you can. With people in other parts of the world, with the hills and rivers, trees and stars. Grieve with them and hope with them. Have planetary feeling. Know that the universe is a communion of subjects and not simply a collection of objects. See something like subjectivity, vital energy, everywhere. Fall in love with the all.

And also be here with your local community, with friends and family, neighbors and strangers close at hand. Don't pretend that you are, or need to be, everywhere. Help your local community become creative, compassionate, participatory, diverse, inclusive, humane to animals, and good for the earth, with no one left behind. Help people in your community know, and be compassionately linked with, people in other communities. Help them understand that we are small but included in the larger web of life. Help them love the local and love the planetary. Call it ecological civilization.

Always listen

Especially if you are in a position of privilege, make sure you listen to other people and also to the more than human world. Let the voices of others enter your ear, let the experiences of others be part of your life. Feel their feelings as best you can, without pretending that they are your own. Don't just listen to what you like; listen to what irritates you, or shocks you, or changes you.

Also listen to your body, to your own feelings, and, as you can, listen for a still small voice inside you which is God's calling. Know that even God begins with listening: with feeling the feelings of all things and responding with fresh possibilities. Listen for the fresh possibilities.

Think small as well as big

We're all familiar with the axiom "think globally, act locally." It's a good one. But it's important to think locally, too. Think small as well as big. Don't pretend that global consciousness is superior to local consciousness, or the other way around. Let the two forms of consciousness be on a par, on the same level. See beauty in those who think locally and encourage them to think globally. And see beauty in those who think globally and encourage them to think locally.

Critique all notions of global thinking that somehow neglect the fact that other creatures matter, too, that the "globe" is not a human globe. And critique all notions of global thinking that neglect just how differentiated and fragmented the world is, ecologically and humanly. Avoid saying "we're all in this together" if there's even a hint that "we" are - or should be - one big, happy, middle class, western family. Be honest about the fragmentation, the brokenness, the injustice.

Seek harmony and unity, but be a champion of differences

It's good to want people and other living beings to dwell in mutually enhancing harmonies. It's good to talk about peace and unity. But also be a champion of differences: different religions, different cultures, different personalities, different animals, different seasons, different landscapes, different moods. Don't fall into the trap of sameness, of presuming that there is one "right" way to be human or to be alive or to exist. Don't let your convictions and views and values become an umbrella that suffocates others. Be glad that there are people who disagree with you. Be glad that not everyone is a process theologian.

Avoid self-absorbed mysticism

It's good to have a mystical side: a sense of the numinous, a feeling of oneness, a love of beauty, a capacity for silence, a heart for the ecstatic. But don't fall into the trap of saying it's all here. Accept the fact that your here is different from the here of someone in another country, a distant city, another zip code, another social class, another race, another religion. Even next door. Give other people space to have their own here: to have feelings and wisdom and beauty that are not your own. Don't pretend that you are disembodied; that your here is everywhere. Let there be many here's, some of which are there for you. Know that being there means honoring the distance and uniqueness of what is here for others.

Remember the cosmic but honor the particular

Remember the cosmic. Don't think that human beings on planet earth are the center of creation. We are small but included in an evolving galactic whole. But also remember that the whole of the universe is contained in each particular, in each grain of sand, and that the individual grains are where the action is.

Know that "everything is interconnected" but also that connections are always unique and specific. Your connections with your parents are different from your connections with best friends, which are different from your connections with small children, which are different from your connections with trees and soil and sunshine. Have affection for the particular, for the small, for the unique, for the specific. Avoid the fallacy of misplaced concreteness.

Avoid cliches and jargon

In explaining process thought to others, or to yourself, avoid cliches to the best of your ability, such as "everything is interconnected" and "the future is open." They grow tiresome and empty. Seek out poets and find fresh ways to say things. Use specific and poetic language when possible, and don't be afraid to appeal to intuition. Remember that, for Whitehead, ideas can be expressed in many different ways and are not reducible to words. They can be expressed through illustrations as well as abstractions. Have a little Zen in you; in explaining how everything is interconnected, offer someone a cup of tea.

Avoid process jargon to the best of your ability. Use only when necessary. It's alright to say "actual entities" every once in a while, but also just say moments of experience. It's alright to say "eternal objects" every once in a while, but also just say the pure potentials. It's alright to say "the consequent nature of God," but also just say God's tenderness or the deep Listening. It's alright to speak of "creative transformation," but also say, with Gerard Manley Hopkins, the freshness deep down. Don't fall into what Whitehead calls the fallacy of the perfect dictionary. Create your own dictionary.

Learn from science and beauty

Remember that for Whitehead the objects in our world are facts, as are our subjective responses to those objects. Science does an excellent job of helping us understand the objects of our world, especially if science is liberated from mechanistic paradigms that forget the qualitative and organic sides of the world. Be willing to critique the mechanism but also learn from the insights. Appreciate the fact that science is evidence-based and try to be evidence based yourself, albeit with an expanded understanding of evidence that includes beauty.

Beauty is the richness of experience found in human life and the more than human world: the harmonies and intensities, sometimes pleasurable and sometimes painful, that are life as lived from the inside. The arts (music, literature, poetry, dance, sculpture, drama) are masters of presenting beauty. And so, in a different but complementary way, are the hills and rivers, trees and lakes, planets and stars. The awe we feel in the presence of a mountain or ocean tell us something about the world no less than a scientific accounts of those immensities. The truths we discern from a really good movie about life on a battlefield are no less valuable than the facts and figures about that battle. A song or dance well performed, that tells us about the cruelties of injustice is as informative, if not more informative, than a more prosaic account of those cruelties. Know that facts include the subjective as well as the objective: in Whitehead's words, the private matters of fact and the public matters of face. Stick to the facts and learn from them all.

Let God be in heaven and on earth.

If you believe in a personal God who has properties such as love and wisdom, and who prefers peace over violence, justice over hatred, let God be there, too. There in your nearby neighbors, there in people in other parts of the world, there in plants and animals. Acknowledge that their ways of knowing God may be very different from your own, and beautiful, too. Be responsible to the face of the other (Levinas). Love their there-ness.

Also, don't talk about divine immanence all the time. Let God have a here of God's own, which is other to your own here. Just as other people transcend you in their uniqueness, and other animals and plants do the same, so let God transcend you. Speak of God as the Deep There. Address God as You who transcends and loves you and you and you.

Celebrate local connections and enjoy life.

Know that life is more than ethics, more than "being good." It's also about gladness and playfulness, wonder and a sense of mystery. About friends and family, music and storytelling. About food and water, bicycles and trees. About laughter and struggle, silence and beauty. Let your here include zest for life. Let it include all the "letters" in the spiritual alphabet: Use your time, energy, and money to help others do the same.