Multiple Religious Belonging

Christian - Unitarian - Universalist - Buddhist

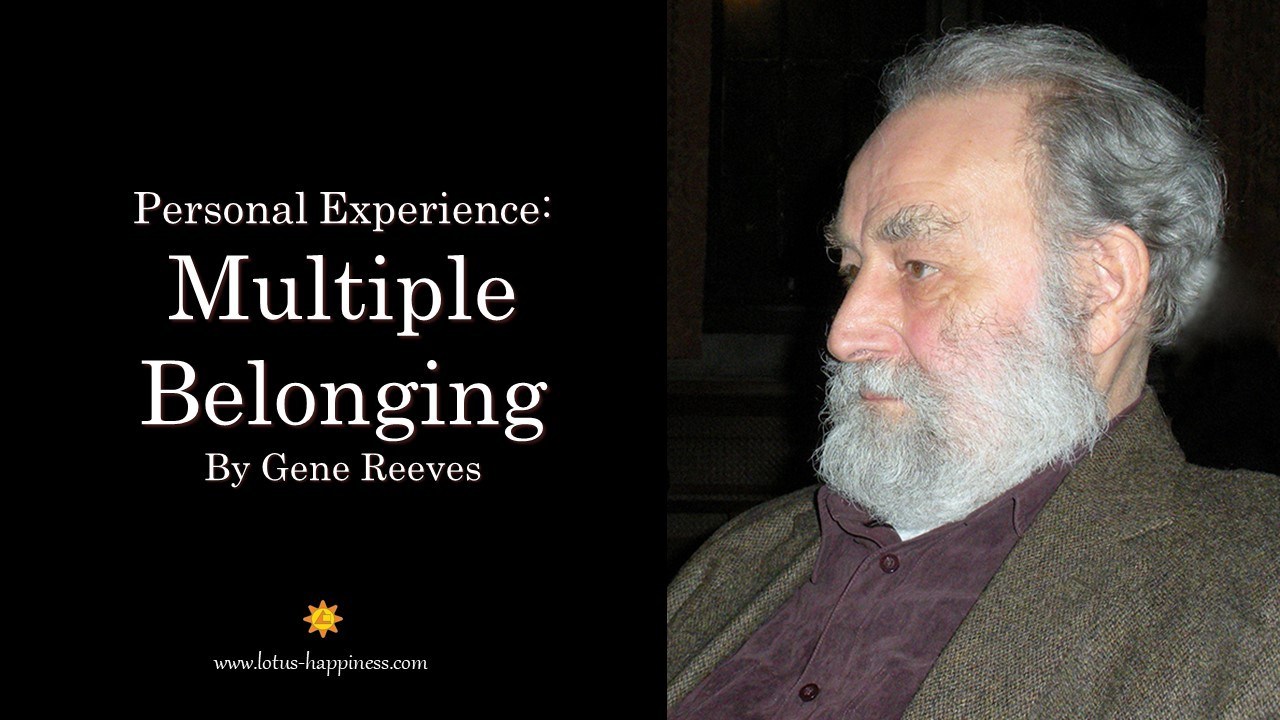

Gene Reeves as a Process Philosopher and

Pioneer in Multiple Religious Belonging

Genes Reeves was a central figure in early process philosophy and theology. The process perspective influenced his way of understanding the four paths that were folded into his life: Christian, Unitarian, Universalist, and Buddhist. As someone very interested in the Christian encounter with Buddhism, I had and have a tremendous admiration for him. I looked up to him in two ways. He was very tall, at least as compared to me. And he was very wise, also as compared to me. He passed away recently, and I offer this page as a testimony to his example, wisdom, and inspiration. He was a pioneer in multiple religious belonging. (Jay McDaniel)

Personal Experience: Multiple Religious Belonging by Gene Reeves

I believe we are called today . . . to move beyond our own tribalisms, our racial and ethnic and national and class smallness, and let our vision of human wholeness become a basis for a more genuine community, a model of what can be. One way [to do this] is by participating in multiple religious traditions.

Personal identity is a tricky thing. I have not always known who I am. Sometimes, perhaps, I tried to find myself. And even now, having entered the ranks of “the elderly,” I’m not sure I know who I am.

Many years ago, when I was invited to preach at the Unitarian Church in Cape Town, South Africa, I wanted to encourage the struggling congregation to broaden their outlook, and for this purpose I chose a passage from the Jewish bible, from the book of Isaiah: “Make your tent larger, lengthen your cords and strengthen your stakes” (54:2).

I explained to the congregation that I was raised Christian. At twenty I became a Unitarian. At thirty I became a Unitarian Universalist. And at fifty I became a Buddhist. But not once did I think of those becomings as a conversion from one faith to another. And so I remain, in my own self-understanding, Christian, Unitarian, Universalist, and Buddhist. The sermon, I claimed in Cape Town, could be understood as Jewish, Christian, Unitarian, Universalist, and Buddhist.

When I was young, even among Christian sects and denominations, being religiously more than one thing was not allowed. My family’s local church was Saint Jude’s, a small, working-class, Episcopal church. Among other responsibilities there, I was the janitor. As janitor, I had keys to the small, three-room building built in the shape of a cross. Late one night, under cover of darkness, I sneaked into the building with one of my best friends, a Roman Catholic, just to show him what the inside of a Protestant church looked like. We had to sneak in because at that time Roman Catholics were not allowed even to enter a Protestant church for any reason.

The Second Vatican Council, often called Vatican II, convened by Pope John XXIII in 1962, pretty much brought an end to that attitude, with Catholics not only allowed to enter non-Catholic facilities and holy places but often encouraged to engage with members of other religious traditions both for improving personal understanding and for benefiting the world. In reference to various discussions before the Second Vatican Council actually convened, Pope John XXIII is often quoted as saying that it was time to open the windows of the Church to let in some fresh air. And he invited organizations outside the Catholic Church to send observers to the Council.

In Cape Town I was suggesting that I am in some ways Jewish, Christian, Unitarian, and Buddhist. Even today, if someone were to ask me whether I am Christian or Unitarian, under most circumstances I would reply in the affirmative. That is basically for two reasons: First, I find that both Christian and Unitarian sensibilities, even biases and prejudices, are deeply imbedded in me, in my values, in my ways of thinking and being. Moreover, there is much in Christian and Unitarian teachings and symbolism that I affirm. I am not a fatalist but believe strongly in the reality and ever-present possibility of personal transformation. I learned that, even took it into my being, from Christianity. I also believe firmly in the importance of respecting other religious traditions. I learned that at a young age from Unitarianism. But there are also other traditions and occupations that are part of my self-identity, some by choice, others by circumstance.

It is common to divide personal identities into two kinds – those that are chosen, often through voluntary association with some group or organization, and those that one inherits or adheres to because of the circumstances one happens to be in. But while this distinction between chosen identities and circumstantial ones can be useful, it is not very clear or strictly applicable.

Take, for example, nationality. I was born and raised as an American. I did not choose to be an American. But I can choose to no longer be an American by resigning my citizenship and becoming, for example, a Japanese citizen. But were I to do that, would I also become Japanese? Hardly! To my way of thinking, being Japanese is at least as much a matter of ethnic identity as it is of nationality. One can become a citizen of Japan, but that is very different, it seems to me, from being “Japanese.” But not everyone thinks the way I do on this matter. So there are, in fact, people who have become citizens of Japan, though they are not ethnically Japanese, who think of themselves, and would like others to think of them, as Japanese, which in at least one sense they actually are. But I would not understand myself to be Japanese even if I became a citizen of Japan.

I am also a professional philosopher and think of myself, to some degree, as a philosopher. Being a philosopher is part of my identity. And it seems to me, it is part of my identity whether I choose it or not. It’s true, of course, that I originally made a choice to study philosophy and, in that sense, to become a philosopher. But since then, it has been part of my identity, part of my being – whether I like it or not. In one sense it is a chosen identity; in another it is not.

Until fairly recently, all of my adult life I have been a university professor. That’s obviously a profession that I chose. But now, in retirement, some still address me as “Professor,” some as “Professor Reeves,” others as “Professor Gene.” Am I, like the colonels, generals, governors, and presidents, to have that title forever? To me it does not seem appropriate, but obviously others have other views. For them, being a professor is part of my identity.

The point I would like to make is that personal identity is not as clear-cut as we sometimes think. Individuals have many identities, some very important to themselves, others not; some chosen, others not; some clearly applicable, others not; some quite permanent, others not.

On Being Buddhist

I have several other identities that might be worth discussing, but the one that I would most like to mention here is that of being Buddhist.

Partly I think because of my history as a Unitarian Universalist minister and the head of a Unitarian Universalist Theological School, I have often been asked whether I am now Buddhist. My usual response is, “Yes, I think so.” That response suggests a kind of ambivalence, an ambivalence not in my own sense of what I am but an ambivalence rooted in a strong sense that many Buddhists would not regard me as Buddhist.

There are several reasons for this. For many Buddhists, the only way to be a “real” Buddhist is to be a monastic, a monk or a nun, and to follow some form of a code of behavior for monastics, the Vinaya. Accordingly, for some Buddhists there are practically no Buddhists in Japan, since even Japanese Buddhist clergy typically marry, eat meat, and drink alcoholic beverages. With such a sense or definition of what it means to be Buddhist, I am clearly not a Buddhist.

East Asia

For more than twenty-five years I have been living in East Asia, primarily in Japan, but also in China, and with occasional extended visits to Taiwan, Korea, and Singapore. In all of these countries, and in other smaller areas with Chinese populations or influence, though they may disagree with each other on many issues, one finds that Confucian values and Confucian sensibilities are still very strong. At the same time, in much of East Asia, Buddhist institutions are also strong and growing stronger, both in numbers and in vitality and cultural influence. Other indigenous traditions, especially Taoism in China and Taiwan and Shinto in Japan, are doing well in various ways, though their institutional embodiments may not be quite as strong as the Buddhist temples and associations. And sometimes these old traditions are embodied in “new” religions, where they attract many adherents. Very often the strong connection between the traditional religious tradition and the new religion is not explicit, and may even be denied, but is there nonetheless. In addition, in many places in East Asia, “foreign” religions, especially Christianity and Islam, are growing and increasing their public prominence.

These countries and cultures are not all the same, not even with respect to religious institutions. For example, Christianity is very strong in Korea and growing rapidly in China, despite government opposition, or perhaps because of it, while in Japan Christians remain a tiny, though influential, presence. But one thing I think all of these countries and cultures have in common is widespread tolerance of multiple religious customs and traditions.

Not only is mutual tolerance widespread in East Asia, so is multiple belonging. Since no one is counting, it is difficult to be precise about this, but it seems as though the majority of people in Japan who support a Buddhist temple or belong to relatively new Buddhist organizations such as Rissho Kosei-kai also occasionally visit and pay their respects at Shinto shrines. In fact, in most of the new lay Buddhist organizations, both Buddhist bodhisattvas and Shinto kami are recognized and incorporated into religious life in various ways. In Rissho Kosei-kai, for example, a Buddhist altar often incorporates a Shinto shrine. In China, too – though in most parts of the country Taoist traditions are not as well institutionalized as Shinto shrines are in Japan – where Taoist temples exist, there does not appear to be much conflict or even tension between Buddhism and Taoism or between being Buddhist and Taoist at the same time. There is even one famous case in Singapore where a large Taoist temple is owned by a nearby Buddhist temple and run by its Buddhist monks.

The big exception to this mutual respect and multiple belonging is the Abrahamic religions of Christianity and Islam, where, for the most part, being a Christian or being a Muslim pretty much precludes being Shinto, Taoist, or Buddhist. This does not mean that there are not exceptions, where, for example, some Japanese Christians are free to participate in Buddhist rituals and may even regard themselves as being Buddhist in some ways. I’m less familiar with Muslims in East Asia, but it seems to me that in both Japan and China there is a strong sense among them of belonging exclusively to Islam.

The point I want to make here, without putting it too strongly, is that in East Asia, more than in the West, there is, and has long been, a kind of openness to participating in and belonging to more than one religious tradition. I have thought that this would be less so among religious professionals, but I will never forget being guided around a Taoist temple in Taiwan by a Buddhist nun, who insisted strongly that even in their most bizarre portrayals the traditional Taoist or popular Chinese gods should be suitably respected and honored. For her, I suppose respect for and even veneration of Taoist and popular deities is not felt to be multiple belonging. It’s just being Chinese. But clearly something like multiple belonging is involved.

In East Asia generally, it seems to me, multiple belonging comes easily. This has not always been true, certainly not everywhere. One does not have to look far to find examples, even today, of extreme intolerance toward other religious traditions. Though not always, very often such intolerance involves, on one side or the other, an Abrahamic tradition, Muslim or Christian. Today in western Myanmar, for example, which is generally a Buddhist country, it is not safe to be Muslim. In parts of Bangladesh, a Muslim country, it is not safe to be Christian or Buddhist. Generally, when such intolerance and hatred of other religious traditions exist, multiple belonging is impossible or at least extremely difficult.

But even with important exceptions, though not often recognized, participation in multiple religious traditions has been going on for centuries. This does not always, perhaps not even often, involve any sense of multiple religious identity. A Japanese Buddhist who goes to a Shinto shrine at New Year’s does not necessarily think of himself or herself as Shinto, just as a young Shinto couple, closely related to a Shinto shrine, who have a Christian-style wedding service do not thereby think of themselves as Christian.

Mutual tolerance and even participation in practices and rituals of other religious traditions do not constitute multiple belonging and do not mean the people involved have a religious identity that is consciously rooted in more than one tradition. But such tolerance and participation do get one close to multiple belonging and open a way, so to speak, at least on reflection, for one to come to see oneself as belonging to more than one tradition.

If we think of multiple belonging as only a matter of chosen, conscious, identity, then perhaps it is no more common in East Asia than it is in America or Europe. But if we can allow that there is such a thing as circumstantial multiple belonging, a multiple belonging that is not so much a matter of consciously chosen personal identity as it is a matter of participating in more than one religious tradition and drawing significant spiritual sustenance from them, perhaps multiple religious belonging is actually quite common in East Asia.

Second Isaiah

Scholarly views of the Old Testament book of Isaiah have changed rather dramatically in recent decades. But I think we need not trouble ourselves with that here. Regardless of what actually happened in history, we have a story, a story that can contribute to our understanding of religious tolerance and multiple belonging.

Around the middle of the sixth century BCE, with the Jews in captivity in Babylon, a prophet arose in their midst. We now know him as Second or Deutero Isaiah, because his story is found in the second section, or second half, of the book of Isaiah. This was an extremely difficult time for the seminomadic Jews. Pinched between Egypt and Babylon, they had been thrown out of their homeland and made captives of the Babylonians. There had been nothing like a functioning Jewish state for several decades, and now Cyrus, the Persian king, was winning battles everywhere and was about to take Babylon itself. To many Jews, there seemed to be no ground for hope. Some even began to doubt the existence of their god, Yahweh.

But this prophet, Isaiah, spoke with a vision, a vision that transcended the present moment and difficulties. Basically he told the exiled Jews two things. First, he assured them that their lives were very important, that they had a purpose in the world and therefore the strength to move forward. “Comfort, comfort my people, says your God. Speak tenderly to Jerusalem, and cry to her, that her warfare is ended, that her iniquity is pardoned” (40:1-2).

“Haven’t you known? Haven’t you heard?” he said. “Your God is everlasting, the creator of the world. He never gets tired or weary, and he strengthens those who are tired and weak” (40:28-29). “The grass withers, the flower fades; but the word of our God will stand forever” (40:8). “Even young people become weak and get weary . . . but those who trust God shall renew their strength, they shall mount up with wings like eagles; they shall run and not be weary; they shall walk and not faint” (40:30-31). And then the prophet promised the people that despite all that had happened, despite their sins and captivity, they would return to Israel and rebuild the Temple and the walls of Jerusalem. So the first part of what the prophet said was a word of comfort, promise, and encouragement.

But the second thing this prophet said was that this was not to be simply another restoration project. “Behold, the former things have come to pass, and new things I now declare” (42:9). “Sing to the Lord a new song” (42:10). “For I create new heavens and a new earth” (65:17). Something new was about to happen, and this new thing was to be a kind of universalism. No more narrowness, no more petty nationalism, no more small-time tribalism.

It is not enough, this prophet said, for Israel alone to be restored. “Behold my servant [Israel], whom I support; my chosen in whom my soul delights; I have put my spirit upon you; you will bring forth justice to the whole world. You will not fail or be discouraged until you have established justice over all the earth” (42:1, 4; emphasis mine). “I have given you as a covenant to all people, a light to all nations, to open the eyes of the blind and to bring from prisons those who sit in darkness” (42:7). “It is too small a thing that you should be my servant to raise up the tribes of Jacob and to restore . . . Israel. I will give you as a light to the nations, that my salvation shall reach the ends of the earth” (49:6). “For my house shall be called a house of prayer for all peoples” (56:7). In other words, no more business as usual. You have a new task as a people – to bring justice to all the earth, that the blind may see and the oppressed be liberated and a covenant made with all peoples.

How was this to be accomplished? Toward the end of the prophecy, the prophet says, “Make your tent larger, lengthen your cords and strengthen your stakes” (54:2).

Make your tent larger. Like those Jews in their Babylonian captivity, I believe we are called today, each one of us is called, to make our tents larger, to move beyond our own tribalisms, our racial and ethnic and national and class smallness, and let our vision of human wholeness become a basis for a more genuine community, a model of what can be.

One way – to be sure, not the only way – to make our tents larger is by participating in multiple religious traditions. By doing so, we can perhaps glimpse, or even come to know deeply, perspectives not our own. We can learn to see the world through the eyes of a Muslim, and thereby even be a Muslim, without casting off the identity with which we entered our too small, but growing, tent.

Source: Dharma World for Living Buddhism and Interfaith Dialogue

Personal identity is a tricky thing. I have not always known who I am. Sometimes, perhaps, I tried to find myself. And even now, having entered the ranks of “the elderly,” I’m not sure I know who I am.

Many years ago, when I was invited to preach at the Unitarian Church in Cape Town, South Africa, I wanted to encourage the struggling congregation to broaden their outlook, and for this purpose I chose a passage from the Jewish bible, from the book of Isaiah: “Make your tent larger, lengthen your cords and strengthen your stakes” (54:2).

I explained to the congregation that I was raised Christian. At twenty I became a Unitarian. At thirty I became a Unitarian Universalist. And at fifty I became a Buddhist. But not once did I think of those becomings as a conversion from one faith to another. And so I remain, in my own self-understanding, Christian, Unitarian, Universalist, and Buddhist. The sermon, I claimed in Cape Town, could be understood as Jewish, Christian, Unitarian, Universalist, and Buddhist.

When I was young, even among Christian sects and denominations, being religiously more than one thing was not allowed. My family’s local church was Saint Jude’s, a small, working-class, Episcopal church. Among other responsibilities there, I was the janitor. As janitor, I had keys to the small, three-room building built in the shape of a cross. Late one night, under cover of darkness, I sneaked into the building with one of my best friends, a Roman Catholic, just to show him what the inside of a Protestant church looked like. We had to sneak in because at that time Roman Catholics were not allowed even to enter a Protestant church for any reason.

The Second Vatican Council, often called Vatican II, convened by Pope John XXIII in 1962, pretty much brought an end to that attitude, with Catholics not only allowed to enter non-Catholic facilities and holy places but often encouraged to engage with members of other religious traditions both for improving personal understanding and for benefiting the world. In reference to various discussions before the Second Vatican Council actually convened, Pope John XXIII is often quoted as saying that it was time to open the windows of the Church to let in some fresh air. And he invited organizations outside the Catholic Church to send observers to the Council.

In Cape Town I was suggesting that I am in some ways Jewish, Christian, Unitarian, and Buddhist. Even today, if someone were to ask me whether I am Christian or Unitarian, under most circumstances I would reply in the affirmative. That is basically for two reasons: First, I find that both Christian and Unitarian sensibilities, even biases and prejudices, are deeply imbedded in me, in my values, in my ways of thinking and being. Moreover, there is much in Christian and Unitarian teachings and symbolism that I affirm. I am not a fatalist but believe strongly in the reality and ever-present possibility of personal transformation. I learned that, even took it into my being, from Christianity. I also believe firmly in the importance of respecting other religious traditions. I learned that at a young age from Unitarianism. But there are also other traditions and occupations that are part of my self-identity, some by choice, others by circumstance.

It is common to divide personal identities into two kinds – those that are chosen, often through voluntary association with some group or organization, and those that one inherits or adheres to because of the circumstances one happens to be in. But while this distinction between chosen identities and circumstantial ones can be useful, it is not very clear or strictly applicable.

Take, for example, nationality. I was born and raised as an American. I did not choose to be an American. But I can choose to no longer be an American by resigning my citizenship and becoming, for example, a Japanese citizen. But were I to do that, would I also become Japanese? Hardly! To my way of thinking, being Japanese is at least as much a matter of ethnic identity as it is of nationality. One can become a citizen of Japan, but that is very different, it seems to me, from being “Japanese.” But not everyone thinks the way I do on this matter. So there are, in fact, people who have become citizens of Japan, though they are not ethnically Japanese, who think of themselves, and would like others to think of them, as Japanese, which in at least one sense they actually are. But I would not understand myself to be Japanese even if I became a citizen of Japan.

I am also a professional philosopher and think of myself, to some degree, as a philosopher. Being a philosopher is part of my identity. And it seems to me, it is part of my identity whether I choose it or not. It’s true, of course, that I originally made a choice to study philosophy and, in that sense, to become a philosopher. But since then, it has been part of my identity, part of my being – whether I like it or not. In one sense it is a chosen identity; in another it is not.

Until fairly recently, all of my adult life I have been a university professor. That’s obviously a profession that I chose. But now, in retirement, some still address me as “Professor,” some as “Professor Reeves,” others as “Professor Gene.” Am I, like the colonels, generals, governors, and presidents, to have that title forever? To me it does not seem appropriate, but obviously others have other views. For them, being a professor is part of my identity.

The point I would like to make is that personal identity is not as clear-cut as we sometimes think. Individuals have many identities, some very important to themselves, others not; some chosen, others not; some clearly applicable, others not; some quite permanent, others not.

On Being Buddhist

I have several other identities that might be worth discussing, but the one that I would most like to mention here is that of being Buddhist.

Partly I think because of my history as a Unitarian Universalist minister and the head of a Unitarian Universalist Theological School, I have often been asked whether I am now Buddhist. My usual response is, “Yes, I think so.” That response suggests a kind of ambivalence, an ambivalence not in my own sense of what I am but an ambivalence rooted in a strong sense that many Buddhists would not regard me as Buddhist.

There are several reasons for this. For many Buddhists, the only way to be a “real” Buddhist is to be a monastic, a monk or a nun, and to follow some form of a code of behavior for monastics, the Vinaya. Accordingly, for some Buddhists there are practically no Buddhists in Japan, since even Japanese Buddhist clergy typically marry, eat meat, and drink alcoholic beverages. With such a sense or definition of what it means to be Buddhist, I am clearly not a Buddhist.

East Asia

For more than twenty-five years I have been living in East Asia, primarily in Japan, but also in China, and with occasional extended visits to Taiwan, Korea, and Singapore. In all of these countries, and in other smaller areas with Chinese populations or influence, though they may disagree with each other on many issues, one finds that Confucian values and Confucian sensibilities are still very strong. At the same time, in much of East Asia, Buddhist institutions are also strong and growing stronger, both in numbers and in vitality and cultural influence. Other indigenous traditions, especially Taoism in China and Taiwan and Shinto in Japan, are doing well in various ways, though their institutional embodiments may not be quite as strong as the Buddhist temples and associations. And sometimes these old traditions are embodied in “new” religions, where they attract many adherents. Very often the strong connection between the traditional religious tradition and the new religion is not explicit, and may even be denied, but is there nonetheless. In addition, in many places in East Asia, “foreign” religions, especially Christianity and Islam, are growing and increasing their public prominence.

These countries and cultures are not all the same, not even with respect to religious institutions. For example, Christianity is very strong in Korea and growing rapidly in China, despite government opposition, or perhaps because of it, while in Japan Christians remain a tiny, though influential, presence. But one thing I think all of these countries and cultures have in common is widespread tolerance of multiple religious customs and traditions.

Not only is mutual tolerance widespread in East Asia, so is multiple belonging. Since no one is counting, it is difficult to be precise about this, but it seems as though the majority of people in Japan who support a Buddhist temple or belong to relatively new Buddhist organizations such as Rissho Kosei-kai also occasionally visit and pay their respects at Shinto shrines. In fact, in most of the new lay Buddhist organizations, both Buddhist bodhisattvas and Shinto kami are recognized and incorporated into religious life in various ways. In Rissho Kosei-kai, for example, a Buddhist altar often incorporates a Shinto shrine. In China, too – though in most parts of the country Taoist traditions are not as well institutionalized as Shinto shrines are in Japan – where Taoist temples exist, there does not appear to be much conflict or even tension between Buddhism and Taoism or between being Buddhist and Taoist at the same time. There is even one famous case in Singapore where a large Taoist temple is owned by a nearby Buddhist temple and run by its Buddhist monks.

The big exception to this mutual respect and multiple belonging is the Abrahamic religions of Christianity and Islam, where, for the most part, being a Christian or being a Muslim pretty much precludes being Shinto, Taoist, or Buddhist. This does not mean that there are not exceptions, where, for example, some Japanese Christians are free to participate in Buddhist rituals and may even regard themselves as being Buddhist in some ways. I’m less familiar with Muslims in East Asia, but it seems to me that in both Japan and China there is a strong sense among them of belonging exclusively to Islam.

The point I want to make here, without putting it too strongly, is that in East Asia, more than in the West, there is, and has long been, a kind of openness to participating in and belonging to more than one religious tradition. I have thought that this would be less so among religious professionals, but I will never forget being guided around a Taoist temple in Taiwan by a Buddhist nun, who insisted strongly that even in their most bizarre portrayals the traditional Taoist or popular Chinese gods should be suitably respected and honored. For her, I suppose respect for and even veneration of Taoist and popular deities is not felt to be multiple belonging. It’s just being Chinese. But clearly something like multiple belonging is involved.

In East Asia generally, it seems to me, multiple belonging comes easily. This has not always been true, certainly not everywhere. One does not have to look far to find examples, even today, of extreme intolerance toward other religious traditions. Though not always, very often such intolerance involves, on one side or the other, an Abrahamic tradition, Muslim or Christian. Today in western Myanmar, for example, which is generally a Buddhist country, it is not safe to be Muslim. In parts of Bangladesh, a Muslim country, it is not safe to be Christian or Buddhist. Generally, when such intolerance and hatred of other religious traditions exist, multiple belonging is impossible or at least extremely difficult.

But even with important exceptions, though not often recognized, participation in multiple religious traditions has been going on for centuries. This does not always, perhaps not even often, involve any sense of multiple religious identity. A Japanese Buddhist who goes to a Shinto shrine at New Year’s does not necessarily think of himself or herself as Shinto, just as a young Shinto couple, closely related to a Shinto shrine, who have a Christian-style wedding service do not thereby think of themselves as Christian.

Mutual tolerance and even participation in practices and rituals of other religious traditions do not constitute multiple belonging and do not mean the people involved have a religious identity that is consciously rooted in more than one tradition. But such tolerance and participation do get one close to multiple belonging and open a way, so to speak, at least on reflection, for one to come to see oneself as belonging to more than one tradition.

If we think of multiple belonging as only a matter of chosen, conscious, identity, then perhaps it is no more common in East Asia than it is in America or Europe. But if we can allow that there is such a thing as circumstantial multiple belonging, a multiple belonging that is not so much a matter of consciously chosen personal identity as it is a matter of participating in more than one religious tradition and drawing significant spiritual sustenance from them, perhaps multiple religious belonging is actually quite common in East Asia.

Second Isaiah

Scholarly views of the Old Testament book of Isaiah have changed rather dramatically in recent decades. But I think we need not trouble ourselves with that here. Regardless of what actually happened in history, we have a story, a story that can contribute to our understanding of religious tolerance and multiple belonging.

Around the middle of the sixth century BCE, with the Jews in captivity in Babylon, a prophet arose in their midst. We now know him as Second or Deutero Isaiah, because his story is found in the second section, or second half, of the book of Isaiah. This was an extremely difficult time for the seminomadic Jews. Pinched between Egypt and Babylon, they had been thrown out of their homeland and made captives of the Babylonians. There had been nothing like a functioning Jewish state for several decades, and now Cyrus, the Persian king, was winning battles everywhere and was about to take Babylon itself. To many Jews, there seemed to be no ground for hope. Some even began to doubt the existence of their god, Yahweh.

But this prophet, Isaiah, spoke with a vision, a vision that transcended the present moment and difficulties. Basically he told the exiled Jews two things. First, he assured them that their lives were very important, that they had a purpose in the world and therefore the strength to move forward. “Comfort, comfort my people, says your God. Speak tenderly to Jerusalem, and cry to her, that her warfare is ended, that her iniquity is pardoned” (40:1-2).

“Haven’t you known? Haven’t you heard?” he said. “Your God is everlasting, the creator of the world. He never gets tired or weary, and he strengthens those who are tired and weak” (40:28-29). “The grass withers, the flower fades; but the word of our God will stand forever” (40:8). “Even young people become weak and get weary . . . but those who trust God shall renew their strength, they shall mount up with wings like eagles; they shall run and not be weary; they shall walk and not faint” (40:30-31). And then the prophet promised the people that despite all that had happened, despite their sins and captivity, they would return to Israel and rebuild the Temple and the walls of Jerusalem. So the first part of what the prophet said was a word of comfort, promise, and encouragement.

But the second thing this prophet said was that this was not to be simply another restoration project. “Behold, the former things have come to pass, and new things I now declare” (42:9). “Sing to the Lord a new song” (42:10). “For I create new heavens and a new earth” (65:17). Something new was about to happen, and this new thing was to be a kind of universalism. No more narrowness, no more petty nationalism, no more small-time tribalism.

It is not enough, this prophet said, for Israel alone to be restored. “Behold my servant [Israel], whom I support; my chosen in whom my soul delights; I have put my spirit upon you; you will bring forth justice to the whole world. You will not fail or be discouraged until you have established justice over all the earth” (42:1, 4; emphasis mine). “I have given you as a covenant to all people, a light to all nations, to open the eyes of the blind and to bring from prisons those who sit in darkness” (42:7). “It is too small a thing that you should be my servant to raise up the tribes of Jacob and to restore . . . Israel. I will give you as a light to the nations, that my salvation shall reach the ends of the earth” (49:6). “For my house shall be called a house of prayer for all peoples” (56:7). In other words, no more business as usual. You have a new task as a people – to bring justice to all the earth, that the blind may see and the oppressed be liberated and a covenant made with all peoples.

How was this to be accomplished? Toward the end of the prophecy, the prophet says, “Make your tent larger, lengthen your cords and strengthen your stakes” (54:2).

Make your tent larger. Like those Jews in their Babylonian captivity, I believe we are called today, each one of us is called, to make our tents larger, to move beyond our own tribalisms, our racial and ethnic and national and class smallness, and let our vision of human wholeness become a basis for a more genuine community, a model of what can be.

One way – to be sure, not the only way – to make our tents larger is by participating in multiple religious traditions. By doing so, we can perhaps glimpse, or even come to know deeply, perspectives not our own. We can learn to see the world through the eyes of a Muslim, and thereby even be a Muslim, without casting off the identity with which we entered our too small, but growing, tent.

Source: Dharma World for Living Buddhism and Interfaith Dialogue

Remembering Gene Reeves

by James Ford, reposted from Patheos (May 9, 2019)

I’m sad to learn of the death of the Reverend Doctor Gene Reeves yesterday, May 8th, 2019. Gene was a Unitarian Universalist minister as well as a Buddhist scholar & teacher. He once wrote, “I was raised Christian. At twenty I became a Unitarian. At thirty I became a Unitarian Universalist. And at fifty I became a Buddhist. But not once did I think of those becomings as a conversion from one faith to another. And so I remain, in my own self-understanding, Christian, Unitarian, Universalist, and Buddhist.”

*

Gene Reeves earned his undergraduate degree at the University of New Hampshire in 1956, an STB from Boston University in 1959, immediately after he was ordained a Unitarian minister, and finally his doctorate from Emory University in 1963. He taught at the university level in China and Japan, and held professorial appointments at the University of Chicago’s Divinity School, Wilberforce, Tufts, and Antioch College.

*

Gene was professor-emeritus at our UU seminary in Chicago, Meadville Lombard, which he also served for a time as dean. In those years he was a prominent process theologian. In 1965 he was among the clergy who answered Martin Luther King’s call to come to Selma. Gene was also a significant figure as a Buddhist teacher affiliated with the Rissho Kosei Kai movement. He spent the bulk of the last quarter of a century in Japan, where he helped to found the International Buddhist Congregation in Tokyo. His translation of the Lotus Sutra is considered one of the best available. He also edited A Buddhist Kaleidoscope: Essays on the Lotus Sutra, as well as the author of Stories of the Lotus Sutra.

Among his notable activities was as one of the planners for the Council for a Parliament of World Religions on the centenary of the original in 1993. He was a signal figure in the International Association for Religious Freedom, served for many years on the Society for Buddhist Christian Studies. While it would be forward to say we were friends, Gene & I corresponded over the years. I found him a wise and generous counselor. And in important ways a mentor. I find myself grief stricken. A light has passed from this world. tThe professor was principally aligned with the Rissho Kosei Kai and his practice as one might infer was deeply rooted in the Lotus Sutra. One practice shared by all within that broad family focused on the sutra was the practice of recitation of the mantra Namu Myoho Renge Kyo. While it is not emphasized within the RKK as much as with others within that Dharma family, the mantra, at least its deeper significances are resonant for all. "

-- James Ford

*

Gene Reeves earned his undergraduate degree at the University of New Hampshire in 1956, an STB from Boston University in 1959, immediately after he was ordained a Unitarian minister, and finally his doctorate from Emory University in 1963. He taught at the university level in China and Japan, and held professorial appointments at the University of Chicago’s Divinity School, Wilberforce, Tufts, and Antioch College.

*

Gene was professor-emeritus at our UU seminary in Chicago, Meadville Lombard, which he also served for a time as dean. In those years he was a prominent process theologian. In 1965 he was among the clergy who answered Martin Luther King’s call to come to Selma. Gene was also a significant figure as a Buddhist teacher affiliated with the Rissho Kosei Kai movement. He spent the bulk of the last quarter of a century in Japan, where he helped to found the International Buddhist Congregation in Tokyo. His translation of the Lotus Sutra is considered one of the best available. He also edited A Buddhist Kaleidoscope: Essays on the Lotus Sutra, as well as the author of Stories of the Lotus Sutra.

Among his notable activities was as one of the planners for the Council for a Parliament of World Religions on the centenary of the original in 1993. He was a signal figure in the International Association for Religious Freedom, served for many years on the Society for Buddhist Christian Studies. While it would be forward to say we were friends, Gene & I corresponded over the years. I found him a wise and generous counselor. And in important ways a mentor. I find myself grief stricken. A light has passed from this world. tThe professor was principally aligned with the Rissho Kosei Kai and his practice as one might infer was deeply rooted in the Lotus Sutra. One practice shared by all within that broad family focused on the sutra was the practice of recitation of the mantra Namu Myoho Renge Kyo. While it is not emphasized within the RKK as much as with others within that Dharma family, the mantra, at least its deeper significances are resonant for all. "

-- James Ford

Gene Reeves Writing: A Sample

Combining Buddhism and Process Philosophy

|

Free PDF of Divinity in Process Thought and the Lotus Sutra

|

e.

"Divinity in Process Thought and the Lotus Sutra" by Gene Reeves is available as a free PDF. Download and enjoy. | ||

The Buddhist Side of Gene Reeves

Lectures by Gene Reeves on the Flower Imagery in the Lotus Sutra

|

|

|

|

|

|