How are things on Planet Earth?

Recently Max Fisher of the Washington Post shared 40 Maps that Explain the World and these maps can help. All forty can be found by clicking here. Below are eight of them.

1. Where are we?

"This NASA moving image, recorded by satellite over a full year as part of their Blue Marble Project, shows the ebb and flow of the seasons and vegetation. Both are absolutely crucial factors in every facet of human existence — so crucial we barely even think about them. It’s also a reminder that the Earth is, for all its political and social and religious divisions, still unified by the natural phenomena that make everything else possible."

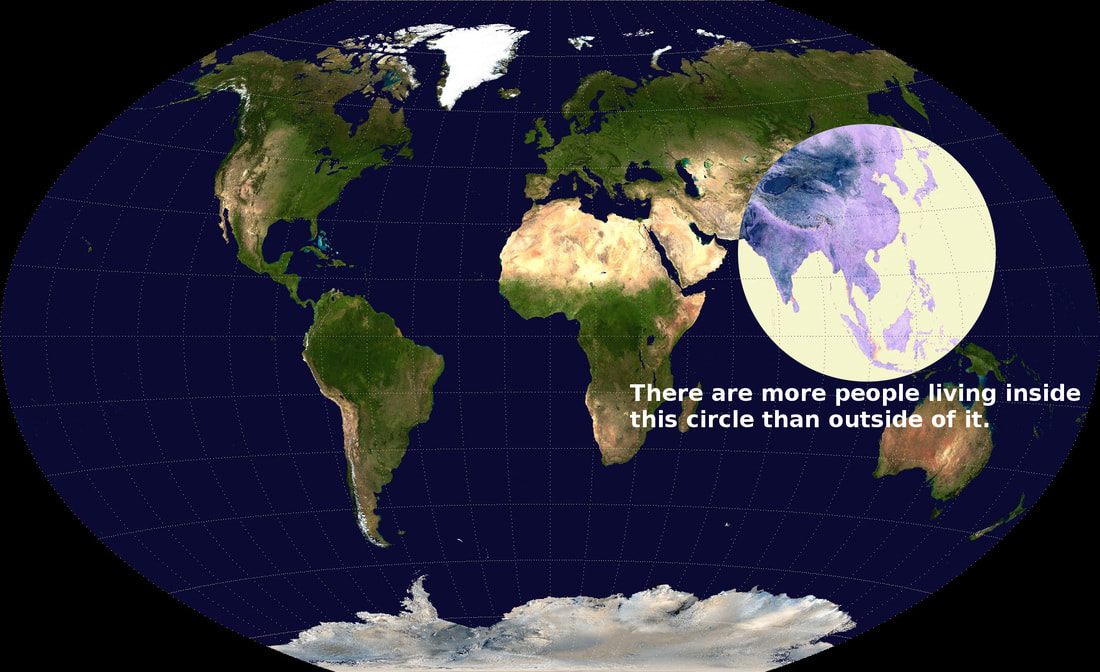

2. Where is everybody?

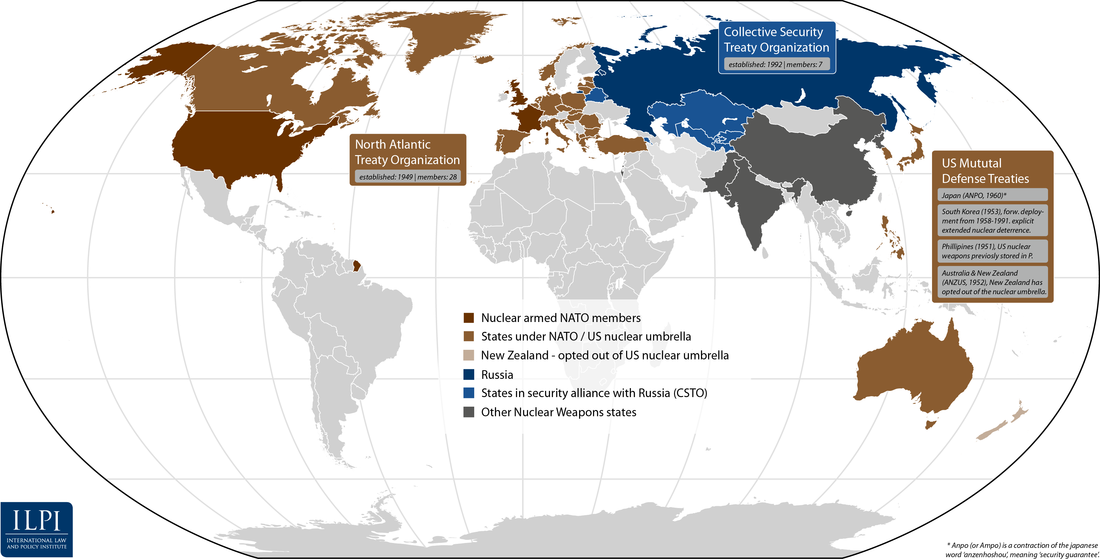

3. Who has the nuclear weapons?

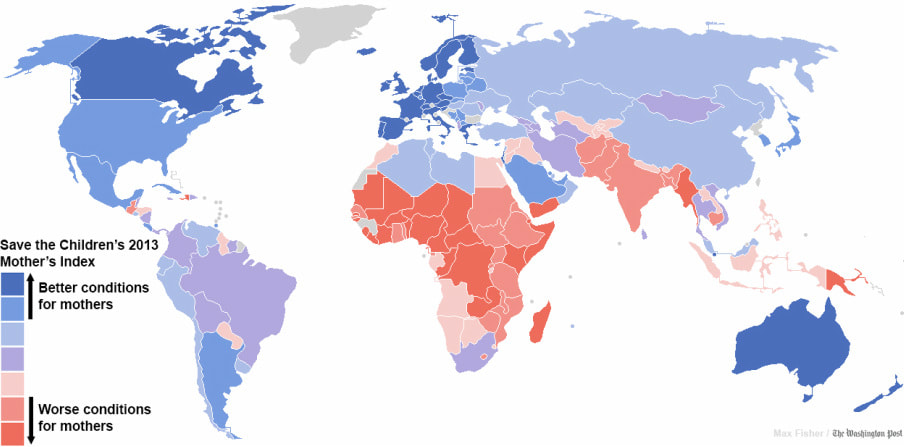

4. Where is it good and where is it bad to be a mother?

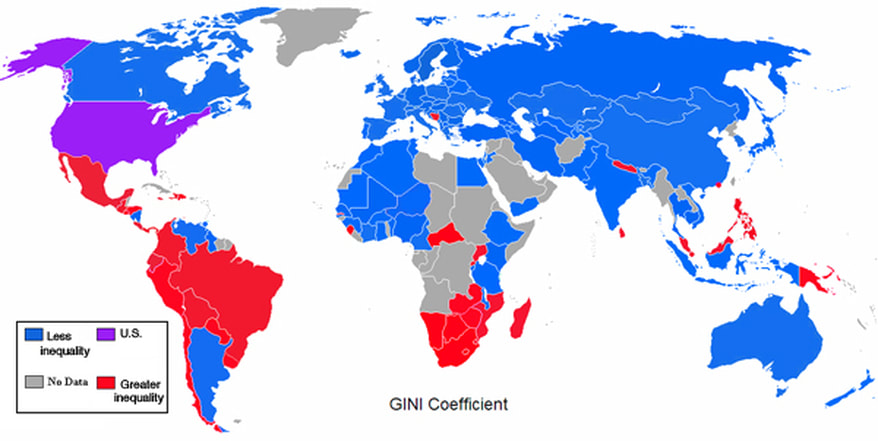

5. Where is economic inequality the greatest?

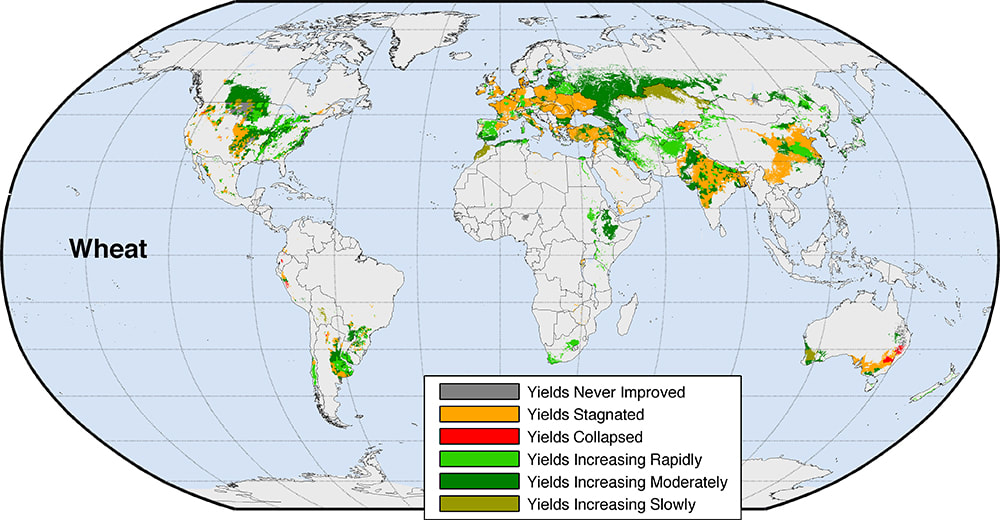

6. Are global crop rates stagnating? (Yes)

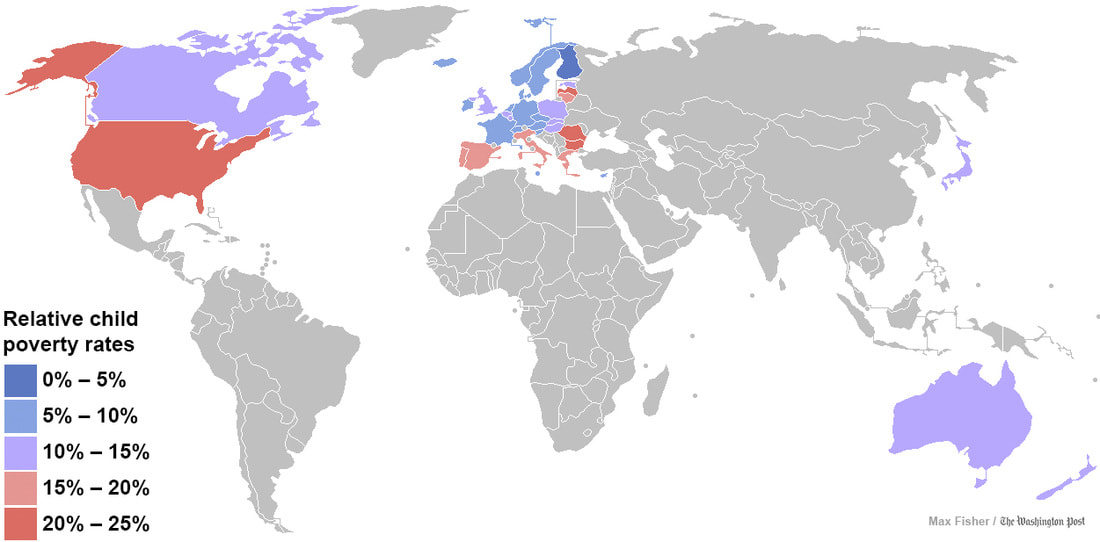

7. Where are child poverty rates the greatest in the developed world?

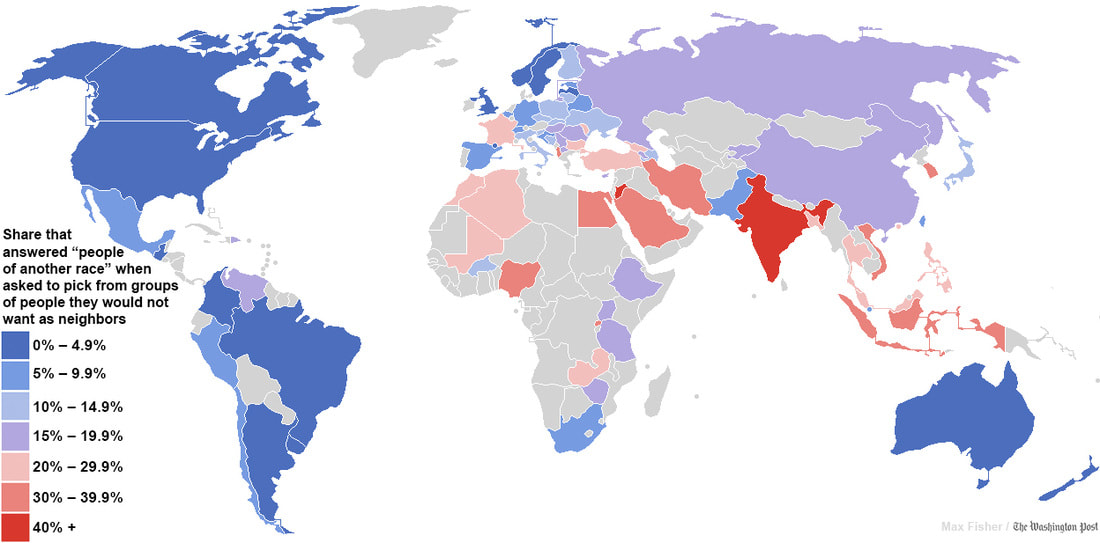

8. What societies are racially tolerant?

World Loyalty

commentary by Jay McDaniel

I don't think we can just recover orthodoxy in that way. I really feel that a whole new language is being created and there's too many people who are struggling with this. I mean, traditional religious language is part of it and will be part of it, but a whole new thing is being created, and it's going to involve other religions. It's going to involve other practices. I don't think you can simply resist it and say, you know, I'm going to just have my little corner and keep it safe and secure.

-- Christian Wiman, editor of Poetry Magazine, in interview with Krista Tippett in On Being

Religion is world loyalty.

-- Alfred North Whitehead, philosopher and mathematician, in Religion in the Making

What does it mean to be loyal to the world? It is not to forego a love of friends and families, of neighbors and strangers in local settings, whom we rightly love as we love ourselves. It is not to think big at the expense of thinking small. If global thinking means local neglect, it is overly abstract and feckless.

Imagine someone who loves the Earth but won't plant a garden, or who loves Justice but doesn't like people. They are disconnected and out of touch with what is immediate and true and beautiful. They can say there but not here.

People who are truly loyal to the world plant gardens and spend time with friends. They seek to reduce suffering in active ways, but they also savor the good things in life: fresh tomatoes, fresh ideas, friends both old and new. They know that stories are always more than numbers, and they like listening to stories -- those of people they know and people they do not know. And they know that we live on a small but gorgeous planet in which each person has a story and every voice counts, not just those close at hand. They remember that other living beings, too, have their stories as do the hills and rivers, landscapes and waterways. There are stories within stories within stories, which together form a republic of stories.

World loyalty is to live wisely and kindly within the republic of stories, seeking the well-being of those close at hand and those far away. Its measure is of well-being is not ever-increasing GDP but rather the flourishing of life in local and distant settings. It sees the world as a community of communities of communities, human and ecological. It prefers life over ideology.

Can religion elicit a sense of world loyalty? Let us hope so. Whitehead says that religion at its best does indeed elicit such loyalty. It moves beyond attachment to particularized ideologies, communities, and practices into a wider fidelity to life itself and a commitment to its flourishing.

But of course we know that religions can unfold in other ways. Religions can promote divisiveness, arrogance, superstition, and violence. We are told that all things evolve over time. All things in nature and all things in society. Can religion evolve, too? Can it move beyond we-they thinking into inclusive hospitality? It is toughest for the evangelizing religions to do this: Christianity and Islam. But all religions have fostered problematic insulariti

The poet Christian Wiman rightly senses that "a whole new thing" is being created today, and needs to be created, in which religious people take delight in the fact that there are other religions. Imagine, then, a local multifaith community in which the participants -- while Jewish or Muslim, Christian or Hindu, Jain or Free Spirit -- are rooted in their faiths but also post-parochial. They will share a common liturgy, a common hope, and it goes like this:

Bread. A clean sky. Active peace. A woman's voice singing somewhere. The army disbanded. The harvest abundant. The wound healed. The child wanted. The prisoner freed. The body's integrity honored. The lover returned....Labor equal, fair and valued. No hand raised in gesture but greeting. Secure interiors - of heart, home, and land -- so firm as to make secure borders irrelevant.

I borrow these words from the poet Robin Morgan, who shared them years ago at a women's conference in Beijing. To live wisely within the republic of stories is to seek something like this for all people in all lands.

The phrase republic of stories comes from another colleague in the spirit, Arlene Goldbard, who uses it in her book The Culture of Possibility: Art, Artists, and the Future. For her a culture of possibility is both an ideal to be approximated and a condition to be enjoyed. Steeped in Jewish wisdom and open to spiritual callings from myriad sources, she believes that our vocation as humans is to avoid self-destruction and build communities that are creative, compassionate, participatory, equitable, and ecologically wise, with no one left behind. She invites us to seize an alternative: to think in ways that transcend homogenizing and mechanistic views of the universe, to engage in community-based practices that help build sustainable communities, and to become alternatives in the very way we live our lives. For more on this approach to life see Seizing an Alternative: Thinking, Practicing, and Being and John Cobb's Ten Ideas for Saving the Planet.

Toward this end we need the arts, we need wise public policy, we need courageous souls, we need spiritual practices, and we need maps. Of course maps are not the territory. The territory consists of the stories themselves, as lived from the inside out. But maps help us get a bigger picture and in this sense they can function as religious icons or, if you will, maps for world loyalty.

Recently Max Fisher of the Washington Post shared 40 Maps that Explain the World and these maps can help. All forty can be found by clicking here. Most of them are maps for where we are now, not where we want to be. Robin Morgan gives us the latter map in words: fresh bread, a clean sky, and no hand raised in gesture except in greeting. It is an ideal to be approximated, the world's best hope.

One more thing before you look at the maps. Maps are like religious icons. They can be helpful or unhelpful depending on the disposition of those who look at them. Some can be downright misleading, although I trust that there are significant degrees of accuracy in those below. The notes beneath each map are those of Max Fisher, as published on August 12, at 11:30 pm in WorldViews by Max Fisher and the Washington Post staff. My own hope is that religiously minded people - and I am among them -- will turn to maps such as these as complements to our faith. Maps can be lures for feeling and invitations for action, In their own ways, like sacred scriptures, they tell stories of where we've been and where we are, so that we can voyage forth in a spirit of world loyalty.

-- Christian Wiman, editor of Poetry Magazine, in interview with Krista Tippett in On Being

Religion is world loyalty.

-- Alfred North Whitehead, philosopher and mathematician, in Religion in the Making

What does it mean to be loyal to the world? It is not to forego a love of friends and families, of neighbors and strangers in local settings, whom we rightly love as we love ourselves. It is not to think big at the expense of thinking small. If global thinking means local neglect, it is overly abstract and feckless.

Imagine someone who loves the Earth but won't plant a garden, or who loves Justice but doesn't like people. They are disconnected and out of touch with what is immediate and true and beautiful. They can say there but not here.

People who are truly loyal to the world plant gardens and spend time with friends. They seek to reduce suffering in active ways, but they also savor the good things in life: fresh tomatoes, fresh ideas, friends both old and new. They know that stories are always more than numbers, and they like listening to stories -- those of people they know and people they do not know. And they know that we live on a small but gorgeous planet in which each person has a story and every voice counts, not just those close at hand. They remember that other living beings, too, have their stories as do the hills and rivers, landscapes and waterways. There are stories within stories within stories, which together form a republic of stories.

World loyalty is to live wisely and kindly within the republic of stories, seeking the well-being of those close at hand and those far away. Its measure is of well-being is not ever-increasing GDP but rather the flourishing of life in local and distant settings. It sees the world as a community of communities of communities, human and ecological. It prefers life over ideology.

Can religion elicit a sense of world loyalty? Let us hope so. Whitehead says that religion at its best does indeed elicit such loyalty. It moves beyond attachment to particularized ideologies, communities, and practices into a wider fidelity to life itself and a commitment to its flourishing.

But of course we know that religions can unfold in other ways. Religions can promote divisiveness, arrogance, superstition, and violence. We are told that all things evolve over time. All things in nature and all things in society. Can religion evolve, too? Can it move beyond we-they thinking into inclusive hospitality? It is toughest for the evangelizing religions to do this: Christianity and Islam. But all religions have fostered problematic insulariti

The poet Christian Wiman rightly senses that "a whole new thing" is being created today, and needs to be created, in which religious people take delight in the fact that there are other religions. Imagine, then, a local multifaith community in which the participants -- while Jewish or Muslim, Christian or Hindu, Jain or Free Spirit -- are rooted in their faiths but also post-parochial. They will share a common liturgy, a common hope, and it goes like this:

Bread. A clean sky. Active peace. A woman's voice singing somewhere. The army disbanded. The harvest abundant. The wound healed. The child wanted. The prisoner freed. The body's integrity honored. The lover returned....Labor equal, fair and valued. No hand raised in gesture but greeting. Secure interiors - of heart, home, and land -- so firm as to make secure borders irrelevant.

I borrow these words from the poet Robin Morgan, who shared them years ago at a women's conference in Beijing. To live wisely within the republic of stories is to seek something like this for all people in all lands.

The phrase republic of stories comes from another colleague in the spirit, Arlene Goldbard, who uses it in her book The Culture of Possibility: Art, Artists, and the Future. For her a culture of possibility is both an ideal to be approximated and a condition to be enjoyed. Steeped in Jewish wisdom and open to spiritual callings from myriad sources, she believes that our vocation as humans is to avoid self-destruction and build communities that are creative, compassionate, participatory, equitable, and ecologically wise, with no one left behind. She invites us to seize an alternative: to think in ways that transcend homogenizing and mechanistic views of the universe, to engage in community-based practices that help build sustainable communities, and to become alternatives in the very way we live our lives. For more on this approach to life see Seizing an Alternative: Thinking, Practicing, and Being and John Cobb's Ten Ideas for Saving the Planet.

Toward this end we need the arts, we need wise public policy, we need courageous souls, we need spiritual practices, and we need maps. Of course maps are not the territory. The territory consists of the stories themselves, as lived from the inside out. But maps help us get a bigger picture and in this sense they can function as religious icons or, if you will, maps for world loyalty.

Recently Max Fisher of the Washington Post shared 40 Maps that Explain the World and these maps can help. All forty can be found by clicking here. Most of them are maps for where we are now, not where we want to be. Robin Morgan gives us the latter map in words: fresh bread, a clean sky, and no hand raised in gesture except in greeting. It is an ideal to be approximated, the world's best hope.

One more thing before you look at the maps. Maps are like religious icons. They can be helpful or unhelpful depending on the disposition of those who look at them. Some can be downright misleading, although I trust that there are significant degrees of accuracy in those below. The notes beneath each map are those of Max Fisher, as published on August 12, at 11:30 pm in WorldViews by Max Fisher and the Washington Post staff. My own hope is that religiously minded people - and I am among them -- will turn to maps such as these as complements to our faith. Maps can be lures for feeling and invitations for action, In their own ways, like sacred scriptures, they tell stories of where we've been and where we are, so that we can voyage forth in a spirit of world loyalty.