- Home

- Process Worldview

- Community

- Art and Music

- Whitehead and Process Thinking

- Podcasts

- Spirituality

- Ecological Civilization

- Education

- Contact

- Social Justice

- Science

- Animals

- Sacred Poems

- Whitehead Videos

- Index of All Titles

- Practicing Process Thought

- Process Spirituality: A Spiritual Alphabet

- Recent Posts

How Duke Ellington Changed my Life

and helped me appreciate Whitehead

by George Hermanson

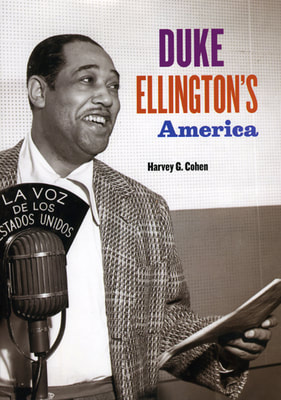

In the New York Review of Books I came across a review of Duke Ellington's America by Harvey Cohen (Oct 28, 2010). The review traces Ellington’s influence on Jazz and how his works helped change the reality of social and jazz history. The review also outlines both the resistance within the jazz community and how his music brought another transformation. It reminded me of Whitehead’s idea of how change comes and how it is also resisted. “But on the whole the social system has been inoculated against the full infection of the principle.” (Adventures of Ideas p 15)

The review reminded me of my own history. In high school music class, I listened to experiments in jazz done by Stan Kenton and Duke Ellington. Those recordings began a sense of music and beauty that also prepared me for an appreciation of classical music, something that was so foreign to me at the time.

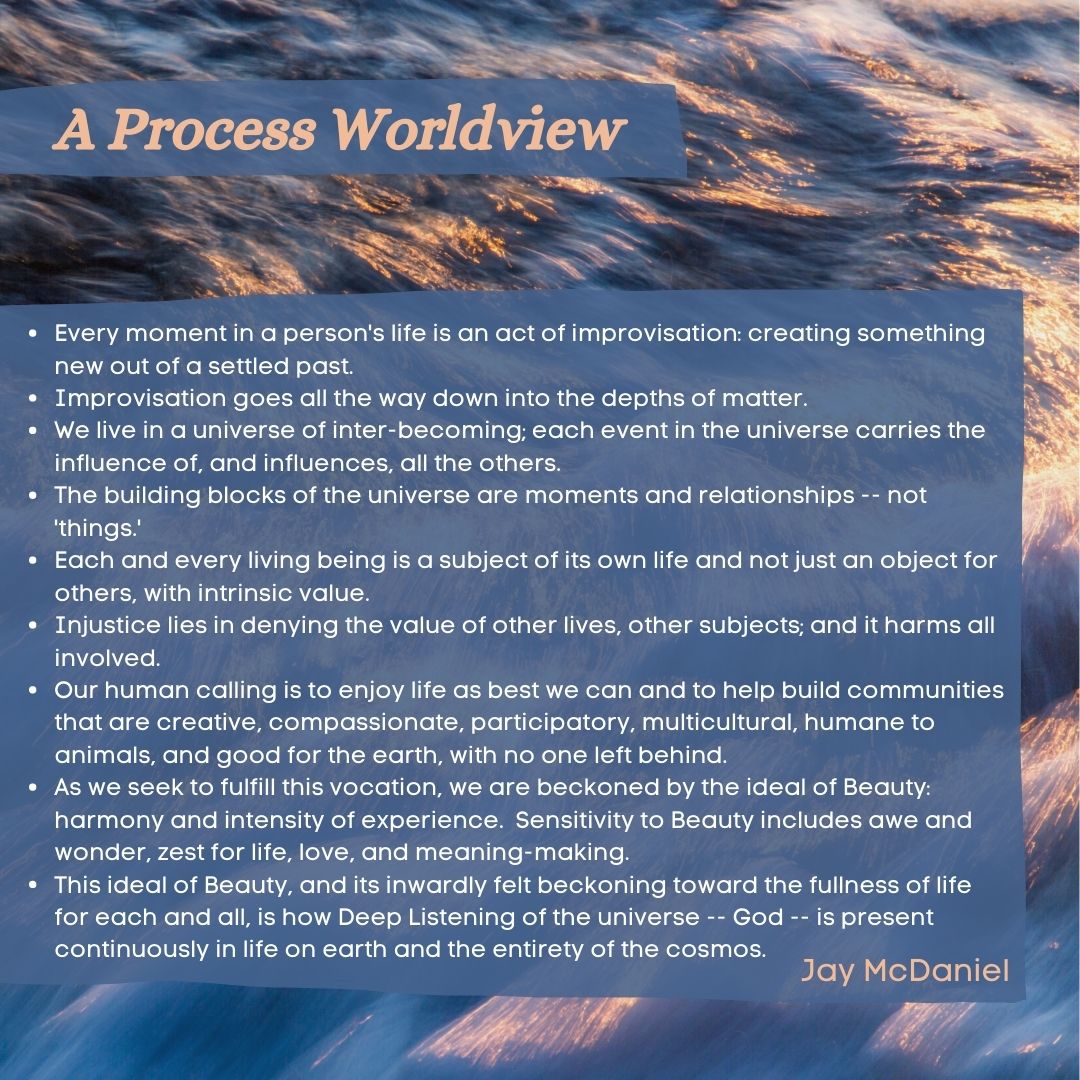

The Duke’s music also introduced me to the issues of a segregated society. Through the music I began to see, the native Canadians who worked on my uncles’ farm. It charmed me into listening to my world in new ways. To hear, through the contrasts and the freedom of the players, a deep listening to the movement of the cosmos and all that lived within. It was a foundation for me to experiment in ideas, and to search for a God who is found in all things. It prepared me to read Whitehead’s Adventures of Ideas and realize that there is a wider world than the narrow confines of middle-class, European existence.

What was unique for me was that Ellington found ways of presenting himself on his own terms, creating his own definition of reality, a definition that the world around him was charmed rather forced into accepting. His music had that effect. And his way is an example of the persuasive power of love - experimenting and being true the lure of a kind of love whom Whitehead names “God.”

The review goes on to remind us that Ellington is a child of America. The subject of the book is Duke Ellington’s America: the America that shaped him, the musical tropes and voices he heard. His drummer said they played and listened to “anything and everything - pop songs, jazz songs. blues, dirty songs, torch songs, Jewish songs.” His music reflected the world he lived in, and through it and his projected self-image, his music played a part of creating a new sense of America, another America that was coming into being. His music is inextricably of piece with the way he lived and thought.

He used his experience of being African and American, and of knowing the history of African Americans in the United States, to compose Black, Brown and Beige: A Tone Parallel of the Negro in America. The response was disappointing, yet he showed through Jazz and this piece the corrosive effects of slavery on slaves and masters alike - “The master carried his fear with him” - and evocations of the ambiguous messages of the white man’s religion. This piece was ahead of its time. For me this was again suggestive of Whitehead’s thesis that change comes about through persuasion not coercion: in this instance the persuasion of music. And I was reminded that persuasion can include vocal lamentation and images of color, too: black and brown and beige. Some people think in words, some in colors, and some in sounds. Ellington invites you to think in all media.

And he invites you to think of worship in such terms. Dave Brubeck carried on that tradition and The Duke influenced many religious thinkers to hear divine love in the improvisation that is the base of Jazz. In talking about the sacred concerts Ellington once said: “Worship is a matter of profound intent. I tried to invite everybody. It is very easy to misunderstand.”

He transformed the currents of music. It is said his personal traits are those associated more readily with those found in religious orders. In the book he emerges as a prophetic figure, luring us with his music. Profound intent sums up his arc of life. Ellington composed his music not as meticulously laid out plans but through a kind of relenting energetic improvisation in the service of deeply held convictions. A reflection of the idea of love working with the world as it is calling out of us in our improvisations a new sense of beauty.

Thank you, Duke Ellington, for helping me see the world so many colors. Black and brown and beige; and red and yellow and white. And thank you for helping me see that the colors of a person’s life are multiple and changing over time. If, as Whitehead suggests, colors are what feelings look like, then none of us are really one color. We are kaleidoscopes, creating new colors as we proceed through life. We cannot be reduced to one color: that would be the fallacy of misplaced concreteness. Nor can we be reduced to who we have been. That would be the fallacy of misplaced concreteness, too. We are improvising our lives, moment by moment, like you. Your music is what our improvisation sounds like.

George Hermanson

The review reminded me of my own history. In high school music class, I listened to experiments in jazz done by Stan Kenton and Duke Ellington. Those recordings began a sense of music and beauty that also prepared me for an appreciation of classical music, something that was so foreign to me at the time.

The Duke’s music also introduced me to the issues of a segregated society. Through the music I began to see, the native Canadians who worked on my uncles’ farm. It charmed me into listening to my world in new ways. To hear, through the contrasts and the freedom of the players, a deep listening to the movement of the cosmos and all that lived within. It was a foundation for me to experiment in ideas, and to search for a God who is found in all things. It prepared me to read Whitehead’s Adventures of Ideas and realize that there is a wider world than the narrow confines of middle-class, European existence.

What was unique for me was that Ellington found ways of presenting himself on his own terms, creating his own definition of reality, a definition that the world around him was charmed rather forced into accepting. His music had that effect. And his way is an example of the persuasive power of love - experimenting and being true the lure of a kind of love whom Whitehead names “God.”

The review goes on to remind us that Ellington is a child of America. The subject of the book is Duke Ellington’s America: the America that shaped him, the musical tropes and voices he heard. His drummer said they played and listened to “anything and everything - pop songs, jazz songs. blues, dirty songs, torch songs, Jewish songs.” His music reflected the world he lived in, and through it and his projected self-image, his music played a part of creating a new sense of America, another America that was coming into being. His music is inextricably of piece with the way he lived and thought.

He used his experience of being African and American, and of knowing the history of African Americans in the United States, to compose Black, Brown and Beige: A Tone Parallel of the Negro in America. The response was disappointing, yet he showed through Jazz and this piece the corrosive effects of slavery on slaves and masters alike - “The master carried his fear with him” - and evocations of the ambiguous messages of the white man’s religion. This piece was ahead of its time. For me this was again suggestive of Whitehead’s thesis that change comes about through persuasion not coercion: in this instance the persuasion of music. And I was reminded that persuasion can include vocal lamentation and images of color, too: black and brown and beige. Some people think in words, some in colors, and some in sounds. Ellington invites you to think in all media.

And he invites you to think of worship in such terms. Dave Brubeck carried on that tradition and The Duke influenced many religious thinkers to hear divine love in the improvisation that is the base of Jazz. In talking about the sacred concerts Ellington once said: “Worship is a matter of profound intent. I tried to invite everybody. It is very easy to misunderstand.”

He transformed the currents of music. It is said his personal traits are those associated more readily with those found in religious orders. In the book he emerges as a prophetic figure, luring us with his music. Profound intent sums up his arc of life. Ellington composed his music not as meticulously laid out plans but through a kind of relenting energetic improvisation in the service of deeply held convictions. A reflection of the idea of love working with the world as it is calling out of us in our improvisations a new sense of beauty.

Thank you, Duke Ellington, for helping me see the world so many colors. Black and brown and beige; and red and yellow and white. And thank you for helping me see that the colors of a person’s life are multiple and changing over time. If, as Whitehead suggests, colors are what feelings look like, then none of us are really one color. We are kaleidoscopes, creating new colors as we proceed through life. We cannot be reduced to one color: that would be the fallacy of misplaced concreteness. Nor can we be reduced to who we have been. That would be the fallacy of misplaced concreteness, too. We are improvising our lives, moment by moment, like you. Your music is what our improvisation sounds like.

George Hermanson

Duke Ellington's Musical Journey

The Character and Mood of My People

from the official Duke Ellington Website:

http://www.dukeellington.com/ellingtonbio.html

When asked what inspired him to write, Ellington replied, "My men and my race are the inspiration of my work. I try to catch the character and mood and feeling of my people".

Duke Ellington's popular compositions set the bar for generations of brilliant jazz, pop, theatre and soundtrack composers to come. While these compositions guarantee his greatness, whatmakes Duke an iconoclastic genius, and an unparalleled visionary, what has granted him immortality are his extended suites. From 1943's Black, Brown and Beige to 1972's The Uwis Suite, Duke used the suite format to give his jazz songs a far more empowering meaning, resonance and purpose: to exalt, mythologize and re-contextualize the African-American experience on a grand scale.

Duke Ellington was partial to giving brief verbal accounts of the moods his songs captured. Reading those accounts is like looking deep into the background of an old photo of New York and noticing the lost and almost unaccountable details that gave the city its character during Ellington's heyday, which began in 1927 when his band made the Cotton Club its home. ''The memory of things gone,'' Ellington once said, ''is important to a jazz musician,'' and the stories he sometimes told about his songs are the record of those things gone. But what is gone returns, its pulse kicking, when Ellington's music plays, and never mind what past it is, for the music itself still carries us forward today.

Duke Ellington was awarded the Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award in 1966. He was later awarded several other prizes, the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 1969, and the Legion of Honor by France in 1973, the highest civilian honors in each country. He died of lung cancer and pneumonia on May 24, 1974, a month after his 75th birthday, and is buried in the Bronx, in New York City. At his funeral attendedby over 12,000 people at the Cathedral of St. John the Divine, Ella Fitzgerald summed up the occasion, "It's a very sad day...A genius has passed."

Duke Ellington's popular compositions set the bar for generations of brilliant jazz, pop, theatre and soundtrack composers to come. While these compositions guarantee his greatness, whatmakes Duke an iconoclastic genius, and an unparalleled visionary, what has granted him immortality are his extended suites. From 1943's Black, Brown and Beige to 1972's The Uwis Suite, Duke used the suite format to give his jazz songs a far more empowering meaning, resonance and purpose: to exalt, mythologize and re-contextualize the African-American experience on a grand scale.

Duke Ellington was partial to giving brief verbal accounts of the moods his songs captured. Reading those accounts is like looking deep into the background of an old photo of New York and noticing the lost and almost unaccountable details that gave the city its character during Ellington's heyday, which began in 1927 when his band made the Cotton Club its home. ''The memory of things gone,'' Ellington once said, ''is important to a jazz musician,'' and the stories he sometimes told about his songs are the record of those things gone. But what is gone returns, its pulse kicking, when Ellington's music plays, and never mind what past it is, for the music itself still carries us forward today.

Duke Ellington was awarded the Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award in 1966. He was later awarded several other prizes, the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 1969, and the Legion of Honor by France in 1973, the highest civilian honors in each country. He died of lung cancer and pneumonia on May 24, 1974, a month after his 75th birthday, and is buried in the Bronx, in New York City. At his funeral attendedby over 12,000 people at the Cathedral of St. John the Divine, Ella Fitzgerald summed up the occasion, "It's a very sad day...A genius has passed."