- Home

- Process Worldview

- Community

- Art and Music

- Whitehead and Process Thinking

- Podcasts

- Spirituality

- Ecological Civilization

- Education

- Contact

- Social Justice

- Science

- Animals

- Sacred Poems

- Whitehead Videos

- Index of All Titles

- Practicing Process Thought

- Process Spirituality: A Spiritual Alphabet

- Recent Posts

I dwell in Possibility – (466)

BY EMILY DICKINSON

I dwell in Possibility –

A fairer House than Prose –

More numerous of Windows –

Superior – for Doors –

Of Chambers as the Cedars –

Impregnable of eye –

And for an everlasting Roof

The Gambrels of the Sky –

Of Visitors – the fairest –

For Occupation – This –

The spreading wide my narrow Hands

To gather Paradise –

A fairer House than Prose –

More numerous of Windows –

Superior – for Doors –

Of Chambers as the Cedars –

Impregnable of eye –

And for an everlasting Roof

The Gambrels of the Sky –

Of Visitors – the fairest –

For Occupation – This –

The spreading wide my narrow Hands

To gather Paradise –

Alfred North Whitehead on Possibility

The value of Whitehead's philosophy is not that he presents a perfect system for understanding reality. Whitehead dismisses that possibility: "how shallow, puny, and imperfect are efforts to sound the depths in the nature of things. In philosophical discussion, the merest hint of dogmatic certainty as to finality of statement is an exhibition of folly." Whitehead's philosophy is systematic, yes. But it is not a perfect system, and its aim is not to get everyone to fit the world into a Whitehead box. It is best understood as a rich and multi-faceted invitation for thinking about and feeling the world in a fresh way and acting out of this freshness.

Possibility: What Can Be

One thing that Whitehead invites us to feel is the presence and role of possibility in human life. Indeed, he suggests that possibility is part of the very fabric of the universe as understood scientically. He's not alone. See, for example, Tim Eastman's Whitehead-influenced proposal, in Untying the Gordian Knot, that potentiality plays a huge role in the dynamics of matter and energy at the quantum level and galactic level no less than the biological and human level. Eastman's point is that from a scientific perspective a potentiality is as real in its way as is an actuality in its way. Eastman agrees with Whitehead. There are two kinds of reality: potentialities and actualities.

The Realm of the Can Be

What is a potentiality? I am using the words potentiality and possibility as equivalents. Whitehead sometimes distinguishes the two, restricting the word "potentialities" to the most abstract kinds of possibilities and the word "possibility" to those which may actually happen in the course of the world. Following his lead I suggest that we speak of two different kinds of possibilities: the highly abstract and the embodied. The most abstract are what Whitehead calls pure potentialities or "eternal objects." Examples would include a seven-dimensional space and a specific shade of the color yellow. They are abstract possibilities that can also be considered intellectually even if they have not been, and will never be, actualized. They are real but not actual. On the other hand there are also real possibilities which have been or can be actualized. Whitehead speaks of these as "impure potentials" or "propositions." An example would be the possibility of going to the store tomorrow. It is a proposition, a proposal, for something that can happen in the world. In what follows, then, I use the word "possibility" to include both pure potentials and impure potentials, timeless potentialities and temporal possibilities, eternal objects and propositions. I want to put in a word for what we might call the subjunctive side of the universe - the Realm of the Can Be - in relation to education and offer an example of how it might work in one of the most important forms of education needed today: Eco-Education.

Possibilities for Physical Arrangement and Possibilities for Subjective Feeling

But first things first. Let us note two kinds of possibility that permeate our lives: (1) possibilities for how things can be arranged or designed in our environments, and (2) possibilities for how we and others might feel, subjectively, if things are arranged that way. These two kinds of distinct but together in much daily and professional life. A landscape artist, a set designer, a graphic designer, an interior decorator, a flower arranger, an architect, a culinary artists, a sound engineer, a restauranteur, a teacher who designs curricula - all are feeling these two kinds of possibilities. They are asking: How would things feel if things were arranged in this way?

Indeed, these two kinds of possibilities are definitive of a designer's vocation in life. A designer is someone who seeks to create a physical, conceptual or digital environment that affords human beings of certain ways of feeling themselves and the world around them. A designer is at home in the Realm of the Possible.

Eco-Education

An educator is likewise at home in the realm of the possible. An educator at any level (pre-kindergarten, primary, secondary, higher) is interested in helping students discover two kinds of possibility: (1) possibilities for objective arrangement in time and space, including possibilities for how they might act in the world and (2) possibilities for subjective feeling. An eco-educator is especially interested in fostering capacities for design that help students feel connected with the more than human world and with one another. The work of Dr. Jillian Judson below is illustrative. She emphasizes three principles: feeling (engaging emotion and imagination), activeness (engaging the body), and place (engaging with context.) In so doing she is helping students discover the possible.

Possibility: What Can Be

One thing that Whitehead invites us to feel is the presence and role of possibility in human life. Indeed, he suggests that possibility is part of the very fabric of the universe as understood scientically. He's not alone. See, for example, Tim Eastman's Whitehead-influenced proposal, in Untying the Gordian Knot, that potentiality plays a huge role in the dynamics of matter and energy at the quantum level and galactic level no less than the biological and human level. Eastman's point is that from a scientific perspective a potentiality is as real in its way as is an actuality in its way. Eastman agrees with Whitehead. There are two kinds of reality: potentialities and actualities.

The Realm of the Can Be

What is a potentiality? I am using the words potentiality and possibility as equivalents. Whitehead sometimes distinguishes the two, restricting the word "potentialities" to the most abstract kinds of possibilities and the word "possibility" to those which may actually happen in the course of the world. Following his lead I suggest that we speak of two different kinds of possibilities: the highly abstract and the embodied. The most abstract are what Whitehead calls pure potentialities or "eternal objects." Examples would include a seven-dimensional space and a specific shade of the color yellow. They are abstract possibilities that can also be considered intellectually even if they have not been, and will never be, actualized. They are real but not actual. On the other hand there are also real possibilities which have been or can be actualized. Whitehead speaks of these as "impure potentials" or "propositions." An example would be the possibility of going to the store tomorrow. It is a proposition, a proposal, for something that can happen in the world. In what follows, then, I use the word "possibility" to include both pure potentials and impure potentials, timeless potentialities and temporal possibilities, eternal objects and propositions. I want to put in a word for what we might call the subjunctive side of the universe - the Realm of the Can Be - in relation to education and offer an example of how it might work in one of the most important forms of education needed today: Eco-Education.

Possibilities for Physical Arrangement and Possibilities for Subjective Feeling

But first things first. Let us note two kinds of possibility that permeate our lives: (1) possibilities for how things can be arranged or designed in our environments, and (2) possibilities for how we and others might feel, subjectively, if things are arranged that way. These two kinds of distinct but together in much daily and professional life. A landscape artist, a set designer, a graphic designer, an interior decorator, a flower arranger, an architect, a culinary artists, a sound engineer, a restauranteur, a teacher who designs curricula - all are feeling these two kinds of possibilities. They are asking: How would things feel if things were arranged in this way?

Indeed, these two kinds of possibilities are definitive of a designer's vocation in life. A designer is someone who seeks to create a physical, conceptual or digital environment that affords human beings of certain ways of feeling themselves and the world around them. A designer is at home in the Realm of the Possible.

Eco-Education

An educator is likewise at home in the realm of the possible. An educator at any level (pre-kindergarten, primary, secondary, higher) is interested in helping students discover two kinds of possibility: (1) possibilities for objective arrangement in time and space, including possibilities for how they might act in the world and (2) possibilities for subjective feeling. An eco-educator is especially interested in fostering capacities for design that help students feel connected with the more than human world and with one another. The work of Dr. Jillian Judson below is illustrative. She emphasizes three principles: feeling (engaging emotion and imagination), activeness (engaging the body), and place (engaging with context.) In so doing she is helping students discover the possible.

Three Principles of Imaginative Ecological Education

in an Ecological Civilization

"Building on the premise that human beings perceive, feel, and think together—that they are, in David Kresch’s neat term “perfinkers”—IEE aims to develop students’ somatic, emotional, and imaginative bonds with the natural world generally, and with specific places in particular, by teaching in ways that engage students as “perfinkers.” IEE has three requirements or principles--Feeling, Activeness, and Place/Sense of Place—that come together in theory and practice to support this aim. We may, indeed, support ecological understanding across the curriculum by teaching in ways that make all learning both imaginative and ecological.

Feeling acknowledges the imaginative core of all learning and of ecological understanding. To engage emotions and imagination in everything we are teaching a cognitive tools approach is required. Activeness acknowledges the central role of the body’s understanding for development of ecological understanding. To experience one’s interconnectedness in a living world one takes time to evoke the body’s tools for learning. Place/Sense of Place acknowledges the role of one’s personal connections with real places for the development a sense of stewardship for the Earth. To nurture relationships with one’s local natural context the teacher will consider how to engage the student’s place-making cognitive tools."

-- from IIE website

Feeling acknowledges the imaginative core of all learning and of ecological understanding. To engage emotions and imagination in everything we are teaching a cognitive tools approach is required. Activeness acknowledges the central role of the body’s understanding for development of ecological understanding. To experience one’s interconnectedness in a living world one takes time to evoke the body’s tools for learning. Place/Sense of Place acknowledges the role of one’s personal connections with real places for the development a sense of stewardship for the Earth. To nurture relationships with one’s local natural context the teacher will consider how to engage the student’s place-making cognitive tools."

-- from IIE website

Making the Connection with

Hopes for an Ecological Civilization

I discovered Dr. Gillian Judson through the work of the Institute for Ecological Civilization. She appeared on one of their videos. The Institute for Ecological Civilization is, to my mind, one of the most important organizations on the planet if we are interested in, well, ecological civilization. And we really need to be interested in it, because it is truly the best and only hope for our fragile species. We must learn to live within, not apart from, the larger web of life, understanding the hills and rivers, plants and animals, as extended family. Not that we would be the first to do this. Indigenous traditions the world over have done this for millennia. But we "moderns" must learn from them and move forward into what, in China, they call a 'constructive' postmodern world. There is no way for this to happen without rethinking education, which takes me to the topic of this page:

My friend tells me that, when she took environmental education in college, she was completely bored. It’s not that she lacked interest in the more than human world: the hills and rivers, the plants and animals. She’s a gardener and forest lover. But for some reason her professor didn’t think it very important to engage the imaginations of his students; the course was almost all about memorizing facts to pass weekly exams. Even the field work, with time spent outside in a nearby park, was almost always about learning names for things, but not about, in her words, "feeling connected" with things, Her professor forgot Whitehead’s idea that good education must include ‘romance’ as well as ‘precision.’ He thought emotions got in the way of learning. Whitehead believed, by contrast, that all human cognition includes emotions, that emotions have wisdom in their own right, and that all learning includes emotions.

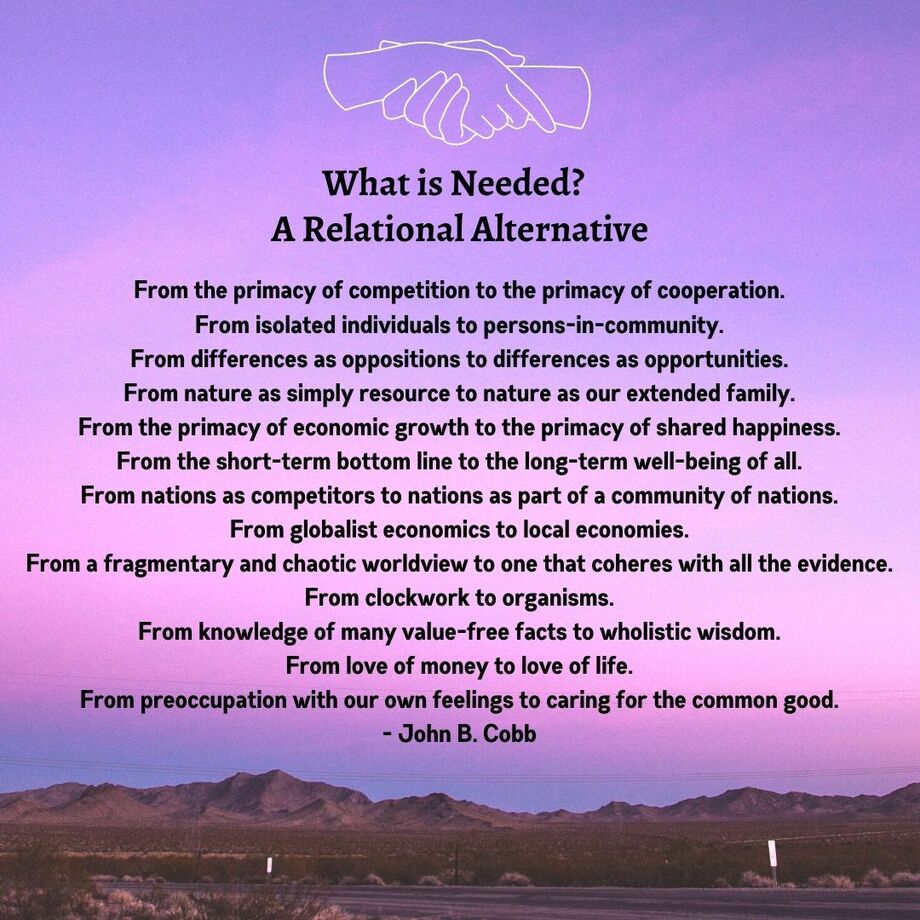

Dr. Gillian Judson has not forgotten Whitehead's insight. She knows that ecological education of any sort must involve engaging student's emotions and imaginations. With a focus on K-12 education, hers is the kind of approach that can serve the needs of those of us who believe education should be in service to the common good of the world: to the development of what, in China and now in other parts of the world, people call ecological civilization. The snapshot below gives you a sense of the overall vision. We call it the relational alternative, and it includes a shift from thinking of 'nature' primarily as a resource for to thinking of it an an extended family to which we humans belong. This is how Gillian Judson thinks of nature, and she thinks far too much environmental education has yet to make this shift.

- Jay McDaniel, Feb. 26, 2021

My friend tells me that, when she took environmental education in college, she was completely bored. It’s not that she lacked interest in the more than human world: the hills and rivers, the plants and animals. She’s a gardener and forest lover. But for some reason her professor didn’t think it very important to engage the imaginations of his students; the course was almost all about memorizing facts to pass weekly exams. Even the field work, with time spent outside in a nearby park, was almost always about learning names for things, but not about, in her words, "feeling connected" with things, Her professor forgot Whitehead’s idea that good education must include ‘romance’ as well as ‘precision.’ He thought emotions got in the way of learning. Whitehead believed, by contrast, that all human cognition includes emotions, that emotions have wisdom in their own right, and that all learning includes emotions.

Dr. Gillian Judson has not forgotten Whitehead's insight. She knows that ecological education of any sort must involve engaging student's emotions and imaginations. With a focus on K-12 education, hers is the kind of approach that can serve the needs of those of us who believe education should be in service to the common good of the world: to the development of what, in China and now in other parts of the world, people call ecological civilization. The snapshot below gives you a sense of the overall vision. We call it the relational alternative, and it includes a shift from thinking of 'nature' primarily as a resource for to thinking of it an an extended family to which we humans belong. This is how Gillian Judson thinks of nature, and she thinks far too much environmental education has yet to make this shift.

- Jay McDaniel, Feb. 26, 2021