- Home

- Process Worldview

- Community

- Art and Music

- Whitehead and Process Thinking

- Podcasts

- Spirituality

- Ecological Civilization

- Education

- Contact

- Social Justice

- Science

- Animals

- Sacred Poems

- Whitehead Videos

- Index of All Titles

- Practicing Process Thought

- Process Spirituality: A Spiritual Alphabet

- Recent Posts

Jeremy Lent's What an Ecological Civilization Looks Like in Yes Magazine is an excellent springboard for thinking about the hopes of the world. It invites us to rethink and work toward a civilization in which we let, in his words, "the design principles of nature' inform our own understanding of what it means to be human and dwell in community with one another and the more-than-human world. He spells out some of the policies and values that would guide society as based on these principles:

However, I read it with four readers in mind: (1) a friend at the local mosque, Sophia Said, with whom I co-chair a weeklly interfaith exploration, (2) a former student, age 24, who finds something 'sacred' in nature itself, who is influenced by Thomas Berry, and counts herself among the spiritual but not religious, (3) a former student, now in seminary preparing for the Christian ministry in the United Methodist Church,herself influenced by open and relational theology, and (4) a scientist friend of mine who, though not a theist, sings of the natural world as containing something like a Spirit of life. These are among the kinds of people I hope will be inspired by the idea of Ecological Civilization.

I think they would have missed four ideas in Lent's presentation which, I fear, would have diminished their enthusiasm:

Without some nod to these four ideas, I think they will not be on board with the idea of ecological civilization, as much as I wish they would. If, as Lent says, there is a wave of young people seeking a new worldview, systems theory won't do it; they will be hesitant to join the wave.

Here are the questions, at least for me.

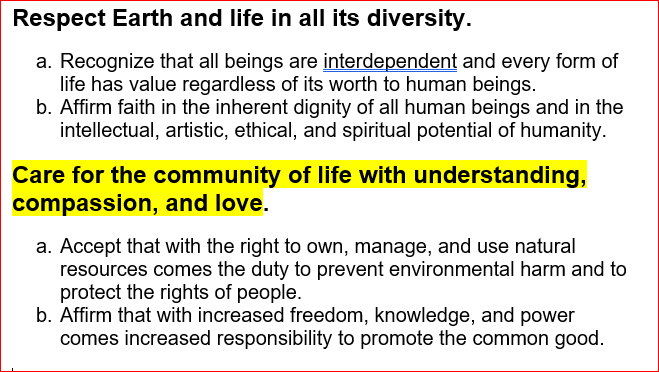

Of course I know that, if we want to appeal to scientists, they are often put off by words that suggest emotion. But isn't this, too, part of the problem. One thing for sure, we need poets not just scientists. The language of the Earth Charter comes so much closer: "Care for the community of life with understanding, compassion, and and love."

*

I did a word search. The words “God” and “Sacred” and “Divine” do not appear in Lent’s excellent article in Yes. Perhaps such words will appear in his forthcoming book, about which I am excited: The word “spiritual” appears once:

Buddhist, Taoist, and other philosophical and religious traditions have based much of their spiritual wisdom on the recognition of the deep interconnectedness of all things.

I wish he’d said just a bit more about those other philosophical and religious traditions. In any case, in place of words like “God” and “Sacred” and “Divine” Lent speaks instead of the natural world as a primary source of revelation, and he seems to think of the natural world as a "system of systems of systems." He then offers “six rules for rejoining the natural world” if we want an ecological civilization.

The rules come from what he calls nature’s intelligence and nature’s wisdom. They (the rules) are “design principles.” You might imagine them as mitvot (commandments) without God. To be sure, some might read Lent’s essay and say to themselves: “But nature is part of God and thus sacred, even if the word isn't used." And some might add "the commandments are indeed sacred commandments; he just doesn’t use the word God." Still, they would miss the words.

Too much System but not enough Love

So many of these friends are Wordsworthians, in that their sensitibilities bear some resemblance to the intuitions of William Wordsworth. I could as easily call them the Daoists or the Native Americans or the Womanists. They believe that the whole universe is, in the words of Thomas Berry, a communion of subjects and not just a collection of objects. It is a community of communities of communities: an Earth community, to use the language of the Earth Charter and Thomas Berry.

The word "system" is used in Lent's essay 33 times. Of course, words have different meanings in different contexts, but often when Wordsworthians hear people using the word “system” they sense that the speakers are picturing something external to themselves, somewhat machine-like, and they are interested in noting and highlighting the myriad connections between its components parts. The relations are object-to-object but not subject-to-subject, and the "I" remains a specator to the system.

To be sure, for Lent and others, what is important about the “system” is that the whole depends on the parts and the parts on the whole. The system – whether a forest or a plant or a human society – is relational. But what troubles the Wordsworthians is the sense of externality (it’s out there) which excludes the subject and the hint of the possibility that it, the system, is closed and bounded, such that if we really understood it, we would have mastered it in some way.

This is not at all Lent’s intention. He is himself amazed by the fractal like creativity of the more than human world. It and the other six principles for design are, for him, a source of wonder. But I wonder if the language of “system” and “rules for design” doesn’t get in the way of the wonder and a recognition that we humans don’t just interact with one another and the more than human world, we are part of what Thomas Berry called a community of subjects. We feel the feelings of one another and the more than human world, and are inwardly formed by their feelings. A simple word for this is empathy. Another is compassion. Neither appear in the essay, and yet both are so essential to any kind of ecological civilization worth living into.

Empathy and Compassion

Consider how he treats symbiosis. It is a relationship between two parties to which each contributes something the other lacks. It is transational but not empathic; fair and just in the human sphere, but not compassion-based.

There is a secret formula hidden deep in nature’s intelligence, which catalyzed each of life’s great evolutionary leaps over billions of years and forms the basis of all ecosystems. It’s captured in the simple but profound concept of mutually beneficial symbiosis: a relationship between two parties to which each contributes something the other lacks, and both gain as a result. With such symbiosis, there is no zero-sum game: The contributions of each party create a whole that is greater than the sum of its parts.

In human society, symbiosis translates into foundational principles of fairness and justice, ensuring that the efforts and skills people contribute to society are rewarded equitably. In an ecological civilization, relationships between workers and employers, producers and consumers, humans and animals, would thus be based on each party gaining in value rather than one group exploiting the other.

Yes to fairness, yes to justice, yes to mutual benefit. But where's the love?

Perhaps philosophies such as that of Whitehead can help, as they combine the best of systems thinking with the best of love thinking. Whitehead proposes that something like "love" - namely the attraction of one entity to another and an aiming toward community -- goes all the down into the depths of matter. He calls it prehending. If we live in a universe of mutual prehension, it would follow that "love" is an expression of, not an exception to, what happens in the very depths of matter, and that "systems" of connection are themselves "communities" in many cases. The universe is not simply a system of systems of systems, but a community of communities of communities, embraced (some would add) by a holy communion that includes any and all in a spirit of love. Not that all in an ecological civilization would think this way, but some would. They would well include my four friends: the Muslim, the None, the Christian, and perhaps, in some way, my biologist friends who sings of Spirit.

However, I read it with four readers in mind: (1) a friend at the local mosque, Sophia Said, with whom I co-chair a weeklly interfaith exploration, (2) a former student, age 24, who finds something 'sacred' in nature itself, who is influenced by Thomas Berry, and counts herself among the spiritual but not religious, (3) a former student, now in seminary preparing for the Christian ministry in the United Methodist Church,herself influenced by open and relational theology, and (4) a scientist friend of mine who, though not a theist, sings of the natural world as containing something like a Spirit of life. These are among the kinds of people I hope will be inspired by the idea of Ecological Civilization.

I think they would have missed four ideas in Lent's presentation which, I fear, would have diminished their enthusiasm:

- a sense of the sacred, including the idea that the earth itself is sacred (especially important to my spiritual but not religious friend)

- a consideration of the idea that there may be a larger life, God, in whose heart the universe unfolds (especially important to my open and relational theology friend)

- a recognition that the universe is a communion of subjects and not just a collection of objects: an Earth Community (especiallly important to my Thomas Berry influenced friend)

- an affirmation of the importance of love in understanding "symbiotic" relations between human beings and with the more than human world (especially important to all of them)

Without some nod to these four ideas, I think they will not be on board with the idea of ecological civilization, as much as I wish they would. If, as Lent says, there is a wave of young people seeking a new worldview, systems theory won't do it; they will be hesitant to join the wave.

Here are the questions, at least for me.

- Do we - advocates of Ecocological Civilization - use the word "system" too much, and the word "love" to little?

- Does our preference for the idea of the earth being a "system of systems of systems" to use the language of a wonderful book by Philip Clayton and Andrew Schwartz called What is Ecological Civilization, reveal a hesitancy or fear on our part of including language that has emotional tones, such as Earth community?

- Might this fear of emotion, this separation of the 'objectifying intellect' from the affective heart, be itself a symptom of the problem we face today, if Ecological Civilizations are to become a reality? The legacy of a dualism that hides from intimacy (another of Thomas Berry's words)

- Might the poetic part of the Earth Charter, with its beautiful injunction to care for the community of life with understanding, compassion and love help us move in the right direction?

- Might the philosophy of Whitehead, with his idea that there is something like feeling and community even in the depths of matter help us follow the lead of the Earth Charter more closely, by imagining a universe in which something like love -- feeling and with with others -- is part of intrinsic value of all things?

Of course I know that, if we want to appeal to scientists, they are often put off by words that suggest emotion. But isn't this, too, part of the problem. One thing for sure, we need poets not just scientists. The language of the Earth Charter comes so much closer: "Care for the community of life with understanding, compassion, and and love."

*

I did a word search. The words “God” and “Sacred” and “Divine” do not appear in Lent’s excellent article in Yes. Perhaps such words will appear in his forthcoming book, about which I am excited: The word “spiritual” appears once:

Buddhist, Taoist, and other philosophical and religious traditions have based much of their spiritual wisdom on the recognition of the deep interconnectedness of all things.

I wish he’d said just a bit more about those other philosophical and religious traditions. In any case, in place of words like “God” and “Sacred” and “Divine” Lent speaks instead of the natural world as a primary source of revelation, and he seems to think of the natural world as a "system of systems of systems." He then offers “six rules for rejoining the natural world” if we want an ecological civilization.

The rules come from what he calls nature’s intelligence and nature’s wisdom. They (the rules) are “design principles.” You might imagine them as mitvot (commandments) without God. To be sure, some might read Lent’s essay and say to themselves: “But nature is part of God and thus sacred, even if the word isn't used." And some might add "the commandments are indeed sacred commandments; he just doesn’t use the word God." Still, they would miss the words.

Too much System but not enough Love

So many of these friends are Wordsworthians, in that their sensitibilities bear some resemblance to the intuitions of William Wordsworth. I could as easily call them the Daoists or the Native Americans or the Womanists. They believe that the whole universe is, in the words of Thomas Berry, a communion of subjects and not just a collection of objects. It is a community of communities of communities: an Earth community, to use the language of the Earth Charter and Thomas Berry.

The word "system" is used in Lent's essay 33 times. Of course, words have different meanings in different contexts, but often when Wordsworthians hear people using the word “system” they sense that the speakers are picturing something external to themselves, somewhat machine-like, and they are interested in noting and highlighting the myriad connections between its components parts. The relations are object-to-object but not subject-to-subject, and the "I" remains a specator to the system.

To be sure, for Lent and others, what is important about the “system” is that the whole depends on the parts and the parts on the whole. The system – whether a forest or a plant or a human society – is relational. But what troubles the Wordsworthians is the sense of externality (it’s out there) which excludes the subject and the hint of the possibility that it, the system, is closed and bounded, such that if we really understood it, we would have mastered it in some way.

This is not at all Lent’s intention. He is himself amazed by the fractal like creativity of the more than human world. It and the other six principles for design are, for him, a source of wonder. But I wonder if the language of “system” and “rules for design” doesn’t get in the way of the wonder and a recognition that we humans don’t just interact with one another and the more than human world, we are part of what Thomas Berry called a community of subjects. We feel the feelings of one another and the more than human world, and are inwardly formed by their feelings. A simple word for this is empathy. Another is compassion. Neither appear in the essay, and yet both are so essential to any kind of ecological civilization worth living into.

Empathy and Compassion

Consider how he treats symbiosis. It is a relationship between two parties to which each contributes something the other lacks. It is transational but not empathic; fair and just in the human sphere, but not compassion-based.

There is a secret formula hidden deep in nature’s intelligence, which catalyzed each of life’s great evolutionary leaps over billions of years and forms the basis of all ecosystems. It’s captured in the simple but profound concept of mutually beneficial symbiosis: a relationship between two parties to which each contributes something the other lacks, and both gain as a result. With such symbiosis, there is no zero-sum game: The contributions of each party create a whole that is greater than the sum of its parts.

In human society, symbiosis translates into foundational principles of fairness and justice, ensuring that the efforts and skills people contribute to society are rewarded equitably. In an ecological civilization, relationships between workers and employers, producers and consumers, humans and animals, would thus be based on each party gaining in value rather than one group exploiting the other.

Yes to fairness, yes to justice, yes to mutual benefit. But where's the love?

Perhaps philosophies such as that of Whitehead can help, as they combine the best of systems thinking with the best of love thinking. Whitehead proposes that something like "love" - namely the attraction of one entity to another and an aiming toward community -- goes all the down into the depths of matter. He calls it prehending. If we live in a universe of mutual prehension, it would follow that "love" is an expression of, not an exception to, what happens in the very depths of matter, and that "systems" of connection are themselves "communities" in many cases. The universe is not simply a system of systems of systems, but a community of communities of communities, embraced (some would add) by a holy communion that includes any and all in a spirit of love. Not that all in an ecological civilization would think this way, but some would. They would well include my four friends: the Muslim, the None, the Christian, and perhaps, in some way, my biologist friends who sings of Spirit.

Elements of the new worldview have emerged in the Earth Charter and Laudato Si |

Waves of young people are looking for a new worldview |