- Home

- Process Worldview

- Community

- Art and Music

- Whitehead and Process Thinking

- Podcasts

- Spirituality

- Ecological Civilization

- Education

- Contact

- Social Justice

- Science

- Animals

- Sacred Poems

- Whitehead Videos

- Index of All Titles

- Practicing Process Thought

- Process Spirituality: A Spiritual Alphabet

- Recent Posts

|

|

|

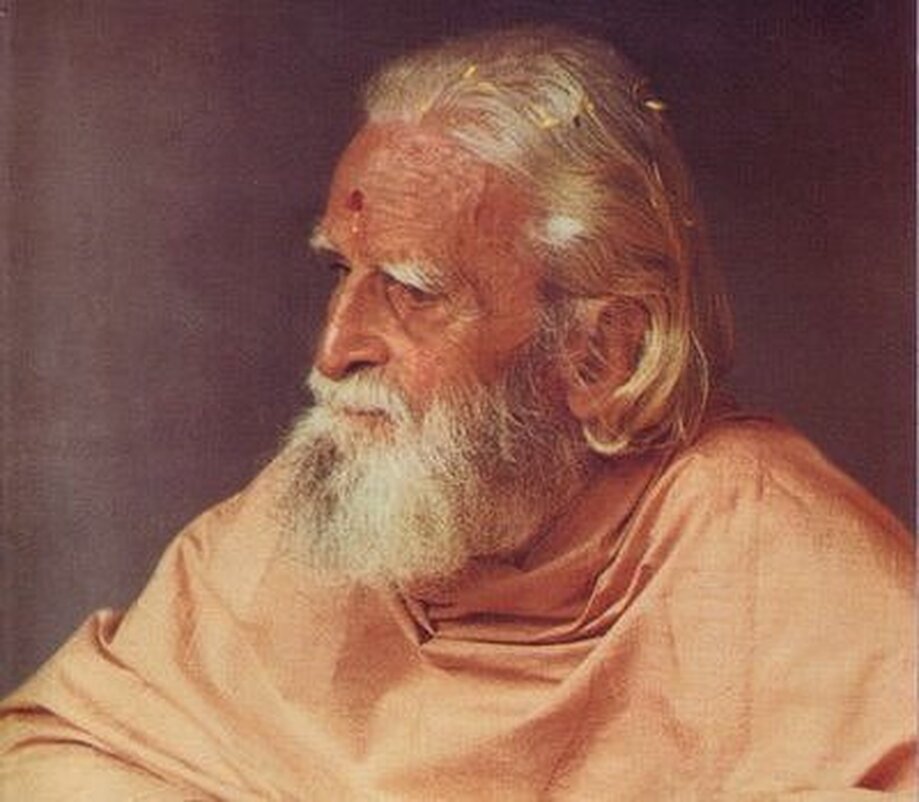

Bede Griffiths OSB Cam, born Alan Richard Griffiths and also known by the end of his life as Swami Dayananda, was a British-born priest and Benedictine monk who lived in ashrams in South India and became a noted yogi.

Brahman and God

Delmar Langbauer's essay "Indian Theism and Process Philosophy" (below) ends by concluding that the Brahman of India philosophy is similar to Whitehead's notion of Creativity as the ultimate reality, and that Whitehead's philosophy also offers a way of appreciating the Hindu idea that the ultimate reality, in addition to being transpersonal, also has a personal or theistic side, namely Isvara. As Langbauer puts it:

"The similarity of the cosmic conception of brahman and the notion of creativity has now been established. The parallel between the Indian view of Isvara and Whitehead’s vision of the divine has also become apparent. These facts serve as further evidence for the validity of these common conceptions from widely differing cultural contexts. They also suggest that Whitehead’s thought might provide the key element for an adequate bridge between Indian and Western philosophico-religious traditions. Lastly, in coherently and adequately relating God and creativity, Whitehead may have implicitly solved the age-old problem of Indian theists. Perhaps the bhakta’s problem of how best to understand Isvara and brahman may yet be resolved. Moreover, if this were done through the use of a system philosophically equal to that of Shankara, theism’s rightful claim to a place in the Indian tradition might again be clear."

Complementary to Langbauer's rich comparisons between Whitehead and Hindu philosophy is that of Jeffery Long in God, Creativity, Monism, and Pluralism: The Mutual Relevance of Process Thought and Hinduism. In this essay Long argues that process thought can benefit Hinduism and that Hinduism can benefit process thought. Whiteheadian thought can benefit Hinduism by:

1. Aiding in the recovery of the concept of māyā as ‘creativity,’ rather than as ‘illusion,’ as it has often been translated in academic scholarship.

2. Aiding in the articulation of the doctrine of the jīva, or soul, by means of the process affirmation of ontological monism with structural dualism.

3. Aiding in the articulation of the religious pluralism of the Ramakrishna tradition with the process concept of the three ultimate realities.

Hinduism can benefit Whiteheadian thought by helping process thinkers refine some of its already-existing ideas:

1. Hinduism sheds light on the process understanding of soul development by affirming that souls have, like God and the world, always existed.

2. The Hindu emphasis on the fundamental unity of existence complements the emphasis of process thought on change and difference.

3. Hinduism demonstrates that a non-omnipotent deity can be worshiped with intensity and devotion, contrary to the claims of classical theology.

Indian Theism and Process Philosophy

by Delmar Langbauer

The following article appeared in Process Studies, pp. 5-28, Vol. 2, Number 1, Spring, 1972. Process Studies is published quarterly by the Center for Process Studies, 1325 N. College Ave., Claremont, CA 91711. Used by permission. This material was prepared for Religion Online by Ted and Winnie Brock. It is reposted with permission of Religion Online.

A great deal of the interest which has recently developed concerning the thought of Alfred North Whitehead has come from the Christian theological community. Studies on the relations of various aspects of Whiteheadian thought to elements of the Judeo-Christian religious tradition continue to appear. On the other hand, little research has been done concerning the relation of the philosophy of organism to Asia's major religions. This is surprising since the possibility of discovering a truly adequate means of relating the intellectual and religious traditions of East and West should provide more than adequate motivation for that task The following study of the Indian religious tradition and ‘Whiteheadian thought is offered from this perspective. Hopefully, illustrating the value of Whitehead’s categories for understanding Indian culture and religion will stimulate further research into the area of East-West comparisons from a Whiteheadian point of view.

The chief problem facing any comparative study involving the Indian religious tradition is the identification of the characteristic elements of that tradition. Its complexity is well known. Where should one begin a study among such diverse elements as Vedic ritual, Upanishadic speculation, devotional theism, Neo-Vedantin philosophy, Tantric mysteries, and modern movements? Perhaps the best approach is one which emphasizes the history of the religious literature. In this way no major element will be omitted and the importance of each aspect can be judged in the light of the entire tradition,

The literature of the Indian religious tradition begins with the Vedas. The hymns of the Rig Veda are believed to have been composed between 1500 and 900 BC. Probably the most striking feature is their conception of deity. Most of the gods are transparent to their natural origins: Agni from fire, Soma from the wine, Usas from the dawn, Dyaus and Varuna from the sky, Surya and Savitri from the sun, the Asvins (twins) from the twilight, and so forth. The explanation for this transparency lies in the halt of the process of personification which produces the notion of deity.1 The evolution of that conception in India stopped halfway between its point of genesis in objects of nature and the very anthropomorphic notion of deity found in the Greek religions. The consequence of this is that the Vedic gods are never completely divorced from the objects of nature which explain their origin. This phenomenon of arrested personification caused a great multiplicity of gods. Because they were so closely related to the power of nature, there tended to be as many gods as there are aspects of nature. They lacked specific qualities and at times merged in character and function. Working against this tendency was the concept of rita. As natural law, it represents a unified and ordered universe. Such a universe has little room for a multitude of indistinct gods. Consequently there was a constant search for a single principle in terms of which the many gods and pluralities of nature might be ordered and explained. Monistic and monotheistic explanations were considered, yet no definitive solution emerged (Rv. X. 129)2

The Vedic search for unity was combined in the Brahmanic period with a quest for the cosmic power associated with sacrificial ritual. According to the priestly theory of the Brahmanas, there is a mysterious power which authorizes the Vedas and renders efficacious the ritual which they command (2:8). It is this same power which relates the microcosm and macrocosm, man and the universe. Thus man and the universe could be related and harmonized by the proper sacrificial ritual. Through their knowledge of Vedic ritual, the priests could manipulate this power. Individuals, gods, and the universe itself were thus dependent on the brahmins for the preservation of cosmic harmony (see: Satapatha Brahmana II. 226; IV. 3.4.4; and XII. 4.4.6). Probably because of the abuses associated with this scheme, a notion developed in the Aranyaka period which explained that the cosmic power might also be known through symbolic meditation upon sacrificial procedure (1:1.35). This in turn led to increased speculation concerning the nature of the mysterious power itself. That speculation was then associated with the older interest in a unifying principle behind natural and divine pluralities. The product of the combination provided the central theme for the Upanishadic literature -- what is the ultimate unity in terms of which all reality might be explained?

The Upanishadic quest for a unity proceeded in two directions: the objective and the subjective. Early Indian sages searched the cosmos for an absolute arid they searched man himself. The objective search was for brahman, the final irreducible unity behind nature and the cosmos. The possibilities considered are many and disparate, often incompatible.3 The subjective quest was for atman, the innermost self. At some point during the early Upanishadic period the objective and subjective quests for unity tended to draw together Often both types of inquiry are presented in the same passage or narrative (Chan. V. 11-18; Brih. II. 1; Kaus. IV) - The search for the self (atman) became confused with the search for the essence of the cosmos conceived personally as atman or purusha. Finally the realization was made that the two quests were in reality one. The unity behind the individual is the unity behind the cosmos. Brahman equals atman (Brih. IV. 4.25; Ait. V. 3; Svet. I. 16; Brih. II, 5.1; etc.). With this new conception of the absolute, each of the two partial elements which formed it were transcended. A higher synthesis was created. The new absolute, brahman, was described as spiritual and indubitable like the essence of the self -- atman. Yet like the earlier conception of brabman. it was also characterized as the objective unity behind the entire universe.

Nevertheless, the situation is not quite so simple. We find the absolute beyond the old subjective and objective unities described in two ways. Hiriyanna has termed these the cosmic and acosmic: "in sonic passages the Absolute is presented as cosmic or all-comprehensive in its nature (saprapanca); in some others again, as acosmic or all-exclusive (nisprapanca)" (7:~9). A typical example of the cosmic description of brahman, brahman understood inclusively, is: containing all works, containing all desires, containing all odors, containing all tastes, encompassing this whole world, the unspeaking, the unconcerned -- this is the Soul of mine within the heart, this is Brahma" (Chan. III. 14.4; cf. III. 14.2-3). Dasgupta suggests the following passages as characteristic descriptions of the cosmic notion of brahman:

"He creates all, wills all, smells all, tastes all, he has pervaded all, silent and unaffected." He is below, above, in the back, in front, in the south and in the north he is all this. "These rivers in the east and west originating from the ocean, return back into it and become the ocean themselves, though they do not know that they are so. So also these people coming into being from the Being, do not know that they have come from the Being" (Chan. III. 14.4; II. 2.2; and VI. 10). (1:I. 49)

According to both Keith and Hume, this is the oldest and most commonly found description of brahman in the Upanishads (9:11. 510f; 8:32-52). Typical expressions of this concept are those in which brahman or the One is described as creating the universe out of itself, and then reentering it as its essence (Brih. 1. 4.7; Chan. VI. 3.3; Tait. II. 6; Ait. III. 11-12). Brahman is thus both source of the universe and is essence dwelling immanently within it.

Perhaps in Western terms the cosmic conception of brahman might best be understood as being itself. In the above quotation from the Chandogya Upanishad, Dasgupta translated it as "the Being" It is inclusive in the sense In which being itself includes all reality. Like the latter, brahman thus conceived Is the source of all existents. It might be thought of as the material cause. It is not an existent, but is the ground or essence of all existents. It unites the one and the many. It is the universal. All existents are individuations or expressions of it.

Probably the most characteristic acosmic or all-exclusive descriptions of brahman may be found in the Brihadaranyaka Upanishad. The negative method is typical:

It is not coarse, not fine, not short, not long, not glowing (like fire), not adhesive (like water), without shadow and without darkness, without air and without space, without stickiness, odorless, tasteless, without eye, without ear, without voice, without winds, without energy, without breath, without mouth (without personal or family name, unaging, undying, without fear, immortal, stainless, not uncovered, not covered), without measure, without inside and without outside. (Brih. III. 8.8; cf. III. 926; Katha III. 15)

In order to prevent one from concluding from this description that brahman is simply void, it is asserted that all that is owes its existence and reality to brahman, "At the command of the Imperishable the sun and the moon stand apart . . . at the command of the Imperishable the earth and the sky stand apart" (Brih. III. 8.9). This exclusive description implies a notion of transcendence. Brahman is not transcendent in the sense in which a monotheistic god transcends the world. Instead, it is transcendent in that it is beyond finite things and the essence of finite things. This notion of transcendence is therefore even more radical than the sense in which cosmic brahman or being itself transcends existents.

It is the acosmic notion of brahman which is associated with what has been called the transcendental subject of knowledge, a conception which plays an especially important role in the teaching of Yajnavalkya in the Brihadaranyaka Upanishad. Brahman is described as the knowing self. It is the ever-regressing self of the subject-object relation. It is the objectifying self which can never be known. It can never be known because when the objectifier becomes objectified, it is no longer subject. It has become object (see: Brih. III. 8-23; Brih. I. 4.7; Chan. VIII. 12.4; Katha IV. 3-4). It is because this subject cannot be known as subject that it is often described negatively. That fact is made clear in the following:

Explain to me him who is just the Brahma present and not beyond our ken, him who is the Soul of all things.

"He is your soul, which is in all things."

"Which one, O Yajnavalkya, is in all things?"

"You could not see the seer of seeing. You could not hear the hearer of hearing. You could not think the thinker of thinking. You could not understand the understander of understanding. He is your soul, which is in all things. Aught else than Him (or, than this] is wretched." (Brih. II. 4.2; cf. Katha III 15; and Mait. VI. 7)4

Here, then, is the acosmic conception of Brahman: all-exclusive, transcendent, inscrutable, the knowing subject.

The cosmic and acosmic descriptions of brahman are two of the three major elements of the Indian religious tradition. The third is the theistic. It is associated primarily with the post-Upanishadic period. The thought of this period has been described as generally realistic, theistic, and emphasizing the cosmic form of the absolute. With that background we can look more specifically at how the development, of theism proceeded.

Indian theism is to be found among those sects which emphasize bhakti, or devotional faith. Vaishnavism and to a lesser degree Saivism are the most important among these sects. The word bhakti and the related words bhagavat and bhagavata are derived from the root bhaj. The oldest meaning of this word is to participate, but in this context it means "to adore." Grierson tells us that according to the Aphorisms of Sandilya (1.2), bhakti is defined as " ‘a[n] affection fixed upon the Lord’; but the word ‘affection’ (anurakti) itself is further defined as that particular affection (rak ti) which arises after (anu) a knowledge of the attributes of the Adorable One" (5:539)5 Rudolf Otto defined bhakti as "faith, filled with love, expressing itself in reverence" (11 :55).

Although important Saivite sects such as Saiva Siddhantam6 are clearly theistic, Vaishnavite history provides more material for the study of Indian theism.7 Vishnu, like Siva. is an old Vedic god who came into prominence at about the same time as Siva but probably in a different part of India. In the Rig Veda he is a minor god, an ally of Indra, known for prowess as a fighter (Rv. IV. 55.4; VII. 99.5; VIII. 10.2). The next step in the evolution of this deity involves the concept of Narayana. Narayana was a supreme being much like Purusha. Purusha was the primeval cosmic person whose sacrifice was used to explain the origin of the world. Narayana too was a supreme being who through sacrifice became the world. In the evolution of Vaishnavite theism, the conceptions of Vishnu and Narayana were joined to form an Important element of the notion of the divine.

Soon after the beginning of the Aryan migrations into India, the occupied portion of the subcontinent is believed to have been divided into two somewhat different religious areas. There was the northern section of India around modern Delhi called the Midland (Madhyadesa). It was the center of the Vedic form of brahmanic religion. To the immediate east and south of the Midland was the other area which might be termed the Outland. Here, brahmanic ritualism played much less of a role and brahmin authority was almost unknown. It was also here that, in contrast to the developments toward monism going on in the Midland, monotheism arose.

All that can be said for certain about Vaishnavite history at this point is that a monotheistic creed developed around Vasudeva, the adorable (bhagavat). Hiriyanna says that, "its essential features were belief in a single personal god, Vasudeva, and in salvation as resulting from an unswerving devotion to him. Briefly, we may say that it resembles the Hebraic type of godhead." (7:100). Otto echoes, "Whatever the earliest expression of the Vishnu-faith may have been, a god, originally a mere tribal deity, gathers to himself, as in Israel, in ever-increasing measure, the position and dignity of complete and unique super-mundane deity" (11 :27f). The increased usage of the term Isvara (lord) for God rather than the Vedic term deva (god) suggests the unique conception of deity that was developing.8

The unknown founder and teacher of this tribe may have been a member of the Satvata sect of the Outland tribe. As is often the case with the founder of a tribe or religion, he was later identified with the god about whom he had preached. Perhaps this is the explanation of the name Vasudeva.9 He also came to be called Krishna through an identification with the sage Krishna about whom there is a tradition reaching back into the Rig Vedic period. We may say then that Krishna Vasudeva, the founder of the Bhagavata religion who later became identified with the god in whom he believed, taught salvation by devotional faith to the one god Vaseduva. Grierson and Bhandarkar explain that he "taught that the Supreme Being was infinite, eternal, and full of grace, and that salvation consisted in a life of perpetual bliss near him" (5:541).10

The second stage in the development of this form of devotional theism is the wedding of the Bhagavata religion and Sankhya philosophy. In its search for a self-understanding, the monistic developments going on within the Midland were anathema to this religion. The quest for an absolute unity within the Vedic tradition was clearly incompatible with the relation between the soul and the lord which was ultimate for the Bhagavatas. Consequently an alliance was made with what may be called the proto-Sankhya philosophy then developing in the Outland (7:270). At that time this philosophy was probably no more than a dualistic world vision based on the principles of prakriti and purusha (matter and spirit). The Yoga system which complemented this basic world view elaborated a technique for the realization of the self (purusha) as independent of prakriti. The association of the Bhagavata tradition with Sankhya-Yoga thought resulted in the former’s adopting the technical term yoga and in taking the name Purusha for Vasudeva, the lord. The new name for the bhagavat opened the way for the later identification of Vasudeva with Narayana, who was conceptually related to Purusha, the original male.

The next stage in the evolution of Indian theism is the crucial one. It is marked by the brahmanization of the theistic tradition. At this point the question of the relation of God or Isvara to the impersonal One of the Upanishadic tradition arises. This development may be seen in the famous story of the Bhagavad Gita. The impetus behind the marriage of the theistic movement to Upanishadic monism was the rise of Buddhism and Jainism in the Outland (7:100; 5:541). Buddhism especially was a genuine threat to the brahmin orthodoxy of the Midland. The latter was prepared to compromise with the theistic sect in order to form a united front with the Bhagavatas against the Buddhists. As for the worshippers of Vasudeva, they too felt attacked by the openly atheistic Buddhists and Jams. At least the brahmins who represented Aryan orthodoxy affirmed an ambiguously defined brahman. Thus the theists of the Outland joined forces with the monists of the Midland and the great question of the precise relation of brahman and Isvara was set for later thought.

The price that orthodoxy was forced to pay for its alliance with theism was twofold. It had to concede to an identification of Vasudeva with the old Vedic god Vishnu, thus granting the former a place in the orthodox Vedic tradition. The other concession was accepting as orthodox Bhagavat monotheism with its bhakti-oriented form of worship and ethic (12:495). The reconciliation of bhakti with the central concepts of Brahmanic and Upanishadic ethics -- karma and jnana -- is particularly obvious in the Gita. A definitive solution to the problem of the relation of brahman and God is much more difficult to end.

In the period shortly after the Gita the identification of Vasudeva with Narayana and Vishnu was completed. More importantly, Bhagavata theism became increasingly dominated by Upanishadic monism. During this later epic period, under the influence of the very old Vedic conception of deity produced by the process of arrested anthropomorphism, the Bhagavatas were led to simply identify their lord Vasudeva with the cosmic conception of brahman. Grierson explains:

In Northern India, where the influence of the Midland was strongest, the Bhagavatas even admitted the truth of brahmanism, and identified the Pantheos with the Adorable, although they never made pantheism a vital part of their religion. It never worked itself into the texture of their doctrines, but was added to their belief as loosely as their own monotheism had been added to the yoga philosophy. (5:542)

This period in the history of Indian thought is found represented in the eighteen Puranas. These books are sectarian in nature, although most of the basic subject matter comes from the epics, especially the Mahabharata. They consistently teach a rather imprecise form of monism in which the conception of God which arose with the Bhagavata cult is identified with the cosmic conception of brahman. This union is the artificial result of the compromise between Bhagavata theism and Upanishadic monism. Other products of the compromise are ambiguities concerning the relation of Vishnu-Vasudeva to other gods and inconsistencies concerning the final end for man."

It was into a religious situation much like the one reflected in the Puranas that Shankara came in the early part of the ninth century. In clarifying the ambiguities which we have mentioned, and in building the most coherent and complete philosophy that India has ever known, he thoroughly undercut the past theistic tradition. He began by distinguishing two levels of knowledge.12 He then used these to reconcile the obvious tensions between the two conceptions of brahman and the idea of a personal God. Brahman conceived cosmically and God are aspects of reality from the perspective of common life. Knowledge of them is avidya. It is true in terms of the phenomenal world. Vidya however, is a higher knowledge. It is the knowledge of the mystic. From this perspective, all reality is brahman, acosmically conceived. It is the consciousness of the transcendental subject. There is complete unity here. Brahman is entirely devoid of qualities, parts, or distinctions. There is no world, no God, no individual. There is only brahman, and brahman is atman.

In spite of Shankara’s genuine interest in devotionalism and the bhakti movements as important for life in the realm of avidya, the implications of his thought soon became clear. Many of the theistic Saivites and especially the Vaishnavites realized that Shankara’s distinctions between ontological and epistemological levels did not really alter the effect of his monistic position. This was so because it was precisely at the level of the most real that they, the bhaktas, affirmed the absolute ultimacy of the God-man relation. Therefore they could not accept unity at that level, whatever concessions might be made on other levels. The result was a reaction against Shankara and monistic thought generally.

This reaction manifested itself in two ways. One was the rise of the powerful bhakti devotionalism in the lives of the alvar, and nayanar poets. The love poetry of this period of Indian literature is characterized by a deep longing for communion with God.13 The other side of the reaction against the rise of Shankara’s Advaita Vedantic thought was a more philosophic one. It manifested itself in a renewed interest in Sankhya philosophy and in a movement away from Upanishadic monism. Its culmination came in the eleventh century with the thought of Ramanuja. He attempted a detailed refutation of much of Shankara’s thought and then went on to provide the final context for modern Indian theism. First, he implicitly rejected the acosmic description of brahman (Sribhasya IV. 2.1-20 in 13:728-743)14 This was done by expanding the cosmic notion so as to include consciousness. Being itself or the cosmic notion was interpreted somewhat idealistically in terms of consciousness. Having done this, Ramanuja could then argue that Upanishadic passages referring to the acosmic conception (as the transcendent conscious subject) really referred to the cosmic notion with the intent of emphasizing its conscious character (Sribhasya III. 2.3 in 13:602; Sribhasya II. 1.9 in 13:421-424).15 Passages referring to the acosmic conception as absolute unity were said to refer to brahman conceived cosmically, but in the unmanifest state. This form of the cosmic conception was then related to God through the use of a body-soul metaphor and a unique substance-accident theory. Brahman and Isvara were said to be related inseparably as are substance and attribute, the latter being the necessary expression of the former. Whatever the philosophic shortcomings of his substance-attribute theory, Ramanuja succeeded in fixing a permanent place for theism in the Indian philosophic tradition.

Since the time of Ramanuja the bhakti tradition has continued down to the present. Yet, Shankara’s thought has tended to dominate later philosophic directions. It may be said that India’s theistic tradition has not produced a system of equal philosophic excellence to that of Shankara. Consequently, a really adequate answer to the bhakta’s problem of the relation of Isvara and brahman has not been given. Also, Indian theists therefore have lacked the conceptual tools to express adequately their faith in terms of their intellectual and cultural tradition. Later philosophers of the Visistadvaita Vedanta school clarified and further elaborated Ramanuja’s thought, but it still lacked the originality, power, and coherence of Shankara’s Advaitic thought. Added to this, after the period of Ramanuja, interest in philosophic thought somewhat declined. Consequently, new attempts to deal philosophically with the problems of theism in the Indian setting were very few. When interest again developed in Indian philosophy during the nineteenth century, attention centered on Advaitic thought. One reason for this may have been the uniqueness of the acosmic notion of brahman which appealed to those with nationalistic interests. Whatever the case, the problem of adequately relating Isvara and brahman remains a contemporary problem for Indian theists.

With this brief outline before us we are now in a position to begin the comparative study. The perspective gained should make it clear that the characteristic elements to be considered in comparison with Whiteheadian thought should be the two conceptions of brahman and the Indian conception of God or Isvara. Yet, the fact is that these three elements are not compatible even within the Indian tradition itself. Given the acosmic conception of brahman as transcendental consciousness, there finally can be neither God nor being itself. There is only brahman, the one alone. Ramanuja’s response to this dilemma was to reject the acosmic notion and develop a philosophy that would adequately relate Isvara and brahman cosmically conceived. Because of the force of Ramanuja’s claim to having systematized the real truths of the Hindu religion, and because of the obvious gains to be realized through the comparison of two culturally different theistic traditions, Ramanuja’s approach will be followed. In developing our comparison with Whiteheadian thought, we will refer only to the cosmic notion of brahman and its relation to the Indian conception of God.

In a general vein, it might first be said that Whitehead’s philosophy and the Indian tradition share a certain unity of vision. Both reject any sort of final metaphysical dualism. For Whitehead, there is a cosmic unity of feeling or experience. It is a consequence of the principle of universal relativity according to which all actual entities participate in each other. It is because this participation constitutes actual entities that they are generically identical. They are all instances of participation, process, or creativity, "the universal of universals characterizing ultimate matter of fact" (PR 31). Creativity is, then, the final explanation for the unity of vision in the philosophy of organism. On the other side, the cosmic conception of brahman grounds all plurality and provides a metaphysical unity in the Indian tradition. The central question is, "what is the relation of creativity and this conception of brahman?" The answer we shall argue is that Whitehead’s description of creativity and the cosmic description of brahman are two descriptions of the same reality.16

Perhaps the best place to begin a comparison of brahman and creativity is with the negative descriptions of both. In the Upanishads, the cosmic conception of brahman is said to he beyond space, time, and causality. Regarding space, brahman is often characterized as being at the same time very small and very large: "smaller than a mustard seed" and "greater than the earth" (Chan. III. 14.3). Further, it is omnipresent, e.g., "that . . . which is above the sky, . . . beneath the earth, that which is between these two" (Brih. III. 8.7; cf. IV. 2.4). The implication of these passages is "a disengagement of brahman from the laws of space, which assigns limits to everything and appoints it a definite place and no other" (3:150-151). There is a similar relation between brahman and time. It is described as being apart from or independent of past and future (Katha II. 14; Brih. IV. 4.15). At other places brahman is pictured as being of infinite duration (Katha III, 15; Svet. V. 13) and of very small moment -- "like a flash of lightning" (Kena 29-30; Brih. II. 3.6).

The implication here is that brahman is limited neither to a particular moment in time nor to existence over a specific extent of time. Rather, time is dependent upon brahman (Svet. VI. 5.6; 1.2). Brahman is also occasionally described as static, as "the Imperishable" (Brih. III. 8). At other times, it is said to be independent of, or different from, both becoming and not becoming (Isa. 12-14). Radhakrishnan has argued that descriptions like the latter indicate that brahman is described as static only to emphasize its independence of causality (12:175). Certainly there is much ambiguity in the texts concerning whether or not brahman is static. Nevertheless, descriptions like the one in Brihadaranyaka II. 3.15 showing brahman as both stationary and moving would seem to support Radhakrishnan’s argument.

Like brahman, creativity too is "beyond" space, time, and causality. It cannot be located in terms of the spatiotemporal continuum. The latter has reference to the interrelation of actual entities rather than to creativity. It can be neither an efficient cause nor the effect of a particular cause. By the ontological principle, causality like spatiotemporal location applies only to actual entities. Creativity however is not an actual entity, but the "ultimate principle" (PR 31, 47). It is a "principle," a "concept," or a "notion". As such, like brahman, it is quite beyond location in terms of space and time. Also, it transcends efficient and final causality.

In addition to descriptions of brahman as transcending space, time, and causality, it was also considered by the Upanishadic sages in terms of the old formula of sat chit anada (being, consciousness, bliss). There is considerable development of thought concerning the relation of brahman and king. The situation is further complicated because although the cosmic conception of brahman is characterized as being, the acosmic is not. Regarding the cosmic conception of brahman, it is often described as being or being itself: "Being . . . , this was in the beginning, one only without a second" (Chan. VI. 2.1; cf. Brih. V. 4). Along with this there is the constant reminder that as being, brahman transcends all beings or particulars. It is not this, not that (neti, neti).

Concerning the relation of brahman and consciousness, there are occasional Upanishadic passages which suggest that it is consciousness (Brih. IV. 4.6; Ait. III) - Yet the fact that brahman is described as the self one step beyond the self in dreamless sleep (turiya) indicates that brahman is beyond consciousness (Mait. VII. 11). As being itself, it must be said to be beyond consciousness. This is so because as universal (Brih. II. 4.12), brahman is beyond all plurality including the subject-object duality of consciousness.

The third element in the traditional threefold characterization of brahman is bliss. Scholars believe the original meaning of the word ananda to have been sexual. In its Upanishadic usage it implies the transcendence of worldly suffering (Brih. III. 5. I) and desires (Brih. IV. 3. 21). It also has reference to the transcendence of the dichotomy between good and evil (Tait. II. 9). The transcendence of these elements is the result of the realization of unity. Suffering, desire, good and evil are all related to individuality. The realization of brahman, conceived cosmically or acosmically, is the "experience" of universality. It must therefore involve a movement away from plurality and experiences related to individuality (Tait. II. 8). As the realization of absolute unity, the bliss of brahman must also transcend all worldly forms of bliss associated with plurality. And for that reason it is quite beyond the powers of normal understanding and appreciation.

Upanishadic discussion of brahman in terms of being, consciousness, and bliss produces little in the way of concrete information concerning brahman. Characterizations of brahman in these terms all have turned out to be negative. Brahman transcends the dichotomy of empirical being and nonbeing. It is even beyond consciousness. Although brahman may positively be said to be bliss, this is a bliss so far removed from any sort of empirically known bliss as to be of little descriptive value. Consideration of brahman in terms of sat chit ananda thus only serves to implicitly emphasize the general teaching of the inscrutability of brahman. In transcending being and consciousness, all normal modes of prehension and understanding also have been eliminated.

Returning to Whitehead’s conception of creativity, only actual entities or clusters of actual entities are beings. Consequently, as an abstraction rather than an actual entity, creativity must be quite other than any being or existent. The parallel with the cosmic conception of brahman is exact Concerning consciousness, creativity too transcends that form of experience. Consciousness is the subjective form of a particular type of feeling, the feeling of the contrast between a nexus of actual entities and a proposition related to the same nexus (PR 407, 372). Creativity is the generic activity related to all types of feeling. Its generality carries quite beyond the realm of consciousness. Further, for Whitehead. "consciousness presupposes experience, and not experience consciousness" (PR 83). Creativity, the most fundamental metaphysical characterization of experience, must therefore transcend consciousness. And, with regard to both creativity and brahman. consciousness may be said to be derivative and secondary.

As to the relation of creativity and the Indian realization of bliss, obviously Whitehead did not address himself to this type of question. Since the philosophy of organism is a study based on general experience, it should come as no surprise that the realization of creativity has not been considered. It is doubtful if, according to the Whiteheadian scheme, creativity could be said to rise to the level of consciousness. Consciousness depends on negation and contrast. That hardly seems compatible with the many Indian descriptions of the bliss of brahman as tranquility, integration, and equanimity. More specifically, consciousness is the subjective form of an intellectual feeling. Feelings are positive prehensions, and prehensions have reference to actual entities and eternal objects. They do not refer to creativity itself. Thus, in any normal sense creativity could not rise to consciousness. That, of course, is just what the Indians have said all along. We are left with the ontic question of whether or not brahman is "realized" The Indian mystical experience certainly occurs. Descriptions of it seem to suggest that there is some form of radical self-awareness in which a living person discovers himself transparent to the very process of concrescence itself. Yet, the idea of such a "realization" sounds strange in terms of the system as it now stands. The question remains as to how one can most adequately account for the acknowledged experience in terms of Whiteheadian categories. That this question stands does not necessarily jeopardize the central argument that brahman and creativity are one.

In terms of being, consciousness, and bliss, it was seen that Upanishadic discussion continually returned to the theme of the inscrutability and indescribability of brahman. Brahman can be neither known nor described. This is because both processes presuppose a duality of subject and object. Yet, brahman is the unity characterizing all particulars. With respect to brahman, there is no subject apart from it to know it. In similar fashion, there is no other in terms of which to describe it since all are expressions of it. Thus brahman is quite beyond knowledge and description. Certainly Whitehead meant much the same when he explained that creativity could not be univocally characterized because of its ultimate generality. Creativity, he said, "is that ultimate notion of the highest generality at the base of actuality. It cannot be characterized, because all characters are more special than itself" (PR 47). In terms of a comparison of negative characterizations, we may thus summarize: both are inscrutable and beyond the realm of univocal definition and description.

Beyond these negative similarities, much can be said concerning the resemblance of the positive explanations of creativity and brahman. Most of these are related to the notion of "being itself’ which has been used to convey aspects of both Charles Hartshorne has emphasized the parallel between creativity and the scholastic notion of being itself. By employing that term he wishes to emphasize its universality. In his own words,

Creativity is not a thing but a concept, a "category," the "universal of universals." It corresponds to ‘being" as such, in the abstract, in some older systems. It is definitely not an agent, but the inclusive aspect of any and every agent, of agents in general. Indeed, it is agency as such, as Whitehead views agency. (6:517)17

Concerning brahman, we have already seen that Dasgupta used the term "Being" in relation to the cosmic conception of brahman. In the Upanishads brahman is often described as creating the universe out of itself and then reentering it as its essence. Descriptions are also common which refer to brahman as "containing" all things, "encompassing" all things, and "pervading" all things. The point behind these and other inclusive characterizations is that all realities are expressions or manifestations of brahman. The importance of Upanishadic representations of brahman as creating and reentering the universe is that brahman also may be viewed as the material cause and universal substance underlying all particular realities. In the Gita, brahman is described as "both the material cause of the universe and the eternal spirit immanent in the universe" (15:338). For Ramanuja, brahman is the material cause in the sense of a universal substance of which all things may be said to be modes (Sribhasya. II.3.17 in 13:539-40.) As has already been concluded from descriptions such as these, the cosmic conception of brahman is like the power of being or being itself. It is the most universal of categories, unknown except in its individual instances. In all these respects brabman and creativity are the same.

Whitehead presented the notion of creativity as follows:

"Creativity" is the universal of universals characterizing ultimate matter of fact. It is the ultimate principle by which the many, which are the universe disjunctively, become the one actual occasion, which is the universe conjunctively. It lies in the nature of things that the many enter into a complex unity. (PR 31; cf. PR 47)

By the phrase "universal of universals characterizing ultimate matter of fact" Whitehead means that creativity is the primary metaphysical principle. It is the most fundamental principle of being. Its ultimacy involves two factors. It is ultimate, first, in "that it constitutes the generic metaphysical character of all actualities; and secondly it is ultimate in the sense that the actualities are individualizations of it" (WM 86) - Like brahman creativity is the most general metaphysical principle and it is also a universal of which all realities are manifestations. Beyond these similarities, this universal substance is operative as the material cause of all existents in the same sense as brahman.

In order to avoid misunderstanding at this point, the particular sense in which creativity may be said to be substance and material cause should be reviewed. By the time of Process and Reality, Whitehead had rejected any notion of substance in a Spinozistic sense. He particularly objected to Spinoza’s conception of substance as eminently real (PR 10-11). He also protested against the modern notion of substance as a "neutral stuff." Yet, he rejected the Aristotelian characterization that emphasized substance as a static substratum most emphatically (PR 79. 43f). Also, for Ramanuja, the conception of brahman as substance does not involve such elements. Although Whitehead rejected the Aristotelian notion of substance as a passively receptive, primary substance, and the Spinozistic conception of substance as an eminently real, efficient and material cause, he did not altogether reject the notion of substance. He recognized the philosophic necessity for a universal substance, and in the philosophy of organism creativity plays this role He explained "‘Creativity’ is another rendering of the Aristotelian ‘matter’ and of the modern ‘neutral stuff.’ But it is divested of the notion of passive receptivity, either of ‘form’ or of external relations" (PR 46; cf. PR 32). For the Whiteheadian scheme, creativity is substance. It is substantial in two senses it is the universal characterizing all particulars, and it constitutes the actuality of entities. It is materially causal. The phrase "materially causal" refers to the existence or "thatness" of reality. It is this "thatness" to which creativity points. It is only in these respects that creativity may be said to be substance, and it is just in these senses that it is like brahman.

Just as it was seen that brahman cannot exist as a particular being, so "creativity exists only in its individual instances" (WA 15). We have already seen how it transcends all kings or particulars. It follows from this fact and the two senses in which creativity is substantial, that it might best be conceived as being itself or the power of being. Certainly this was Hartshorne’s meaning when he compared creativity with being as such and agency as such. In all these ways, then, creativity and brahman are identical in their relation to being itself. While both being and creativity are beyond the contrast between the static and the dynamic as it applies to actualities, being itself might be understood in terms of either one. On the other hand, because of the continuous interaction of the one and the many, creativity may only be interpreted in terms of the dynamic.

The materials of the Indian scriptural tradition do not dearly affirm brahman as either static or dynamic. Generally it was seen described as "imperishable," or as independent of both becoming and not becoming. Yet occasionally the texts affirmed it as moving or dynamic. Brihadaranyaka II. 3.1-5 referred to it as ‘unformed, real, noumenal, immortal, moving, and yon." In the Gita it is once described as "unmoved," "yet moving indeed" (BhG, XIII. 15). Radhakrishnan’s response to this ambiguity is to argue that statements affirming brahman as static are intended only to indicate brahman’s independence of the laws of causality. His own words are:

This way of establishing Brahman’s independence of causal relations countenances the conception of Brahman as absolute self-existence and unchanging endurance, and leads to misconceptions. Causality is the rule of all changes in the world, But Brahman is free from subjection to causality. There is no change in Brahman though all change is based on it. There is no second outside it, no other distinct from iL We have to sink all plurality In Brahman. All proximity in space, succession In time, interdependence of relations rest on it. (12:175)

Although there is no avoiding the fact that the Indian tradition is rather silent on the question of whether or not brahman is dynamic, Radhakrishnan has here raised the more fundamental elements involved in that question and provided material for comparison at this deeper level.

If brahman is free from subjection to causality, so is creativity. This is the case because. with the exception of material causality. causality only applies to actual entities. We have seen that this is implied in the ontological principle also called the "principle of efficient, and final, causation" (PR 37). According to it. only actual entities can function as efficient causes. Creativity, which is a principle or category rather than an actual entity, must therefore be independent of these types of causality which apply to actual entities. In a similar way, as "there is no change in Brahman, though all change is based on it." the same could be said of creativity.

In the Whiteheadian system change applies neither to creativity nor to any particular actual entity. To explain this, a few words must be said about Whitehead’s notion of the extensive continuum. The extensive continuum is the background matrix in terms of which all actual entities become. It includes all actual entities. It is the total coordination of the standpoints of all actual entities in terms of each other. In Whitehead’s terms: "An extensive continuum is a complex of entities united by the various allied relationships of whole to part, and of overlapping so as to possess common parts, and of contact, and of other- relationships derived from these primary relationships" (PR 103). Each actual entity receives its location in terms of this continuum along with its initial aim from God. Consequently "all actual entities are related according to the determinations of this continuum" (PR 103). Space, time, and change describe the relations of various actual entities in terms of this continuum. Thus, they do not refer to either a particular actual entity or creativity itself. Specifically, change characterizes neither creativity nor actual entities. "An actual entity never moves: it is where it is and what it is" (PR 113) in terms of the extensive continuum. The doctrine of internal relations which underlies the process of concrescence makes it impossible to attribute change to any actual entity" (PR 92). Rather, "change is the difference between actual occasions in one event" (PR 124). For the philosophy of organism, changes are a function of the relation of actual entities in an event with respect to the extensive continuum. It is quite as inapplicable to creativity as it is to brahman. Yet as change and relation are dependent upon brahman, so too they may be said to depend on creativity. This follows by simple logic. Change and spatiotemporal relations are a function of the relations of actual entities within an event. Each of these actual entities is a particular instance of creativity, its material cause. Thus, finally, change is dependent upon creativity, the substance of actual entities.

Associated with this parallel in regard to change, more may be said concerning the similarity between brahman and creativity with respect to time. Radhakrishnan has said of the relation of time and brahman,

It is true that the absolute is not in time, while time is in the absolute. Within the absolute we have real growth, creativity, evolution. The temporal process is an actual process, for reality manifests itself in and through and by means of the temporal changes. If we seek the real in some eternal and timeless void, we do not find it. All that the Upanishads urge is that the process of time find its basis and significance in an absolute which is essentially timeless. (12:198)

Brahman itself is timeless but grounds time. Yet, in a more specific sense than just mentioned above, creativity too is timeless and grounds time. This is not a timelessness like the static atemporality associated with eternal objects, but rather timelessness of another sort. It is the entire point of the epochal conception of time. According to Whitehead, "there is a becoming of continuity, but no continuity of becoming. The actual entities are the creatures which become, and they constitute a continuously extensive world. But, they are not temporally extensive. In other words, extensiveness becomes, but ‘becoming’ is not extensive" (PR 53). Time does not refer to actual entities. As actual entities emerge into existence, they pass instantaneously into objective immortality. The phases of concrescence have no temporal extension. Time has reference to the extensive world rather than to actual entities in themselves. It is a reality of measurement referring to the interrelations of actual entities which have already come into existence. This measurement is possible because, although there is no continuity of becoming, there is a becoming of continuity. Time is a function of that becoming or creativity expressed in actual entities. As such, it is dependent upon creativity. Creativity is in turn independent of its. The parallel with brahman and time is exact.

Another deeper issue connected with the question of the relation between brahman and creativity as process or becoming concerns the classical philosophic problem of the one and the many. Creativity is process in the sense that it is the movement of the many to a new unity which reestablishes plurality. For the Indian scriptural tradition, although there is no explicit literary teaching as to whether or not brahman is dynamic, there is the affirmation that it is the key to the problem of the one and the many. Thus at the level of this deeper question, there is material available for comparison, as well as the suggestion of a parallel.

Obviously, as the one universal substance and material cause of all actualities, brahman and creativity both may be said to be the one which unites the many. Dasgupta has pointed this out in connection with the characterization of brahman in the Gita (1:II. 474f). Yet one can go even further in comparing how these two universals are related to the many. This can be done by considering Ramanuja’s treatment of the problem.

He dealt with the problem of the one and the many in the context of the relation of substance and attribute. Brahman is the one universal substance of which there are many modes (prakara) or attributes. God and souls are, for example, combinations of these attributes. Ramanuja’s dilemma is this: how can one philosophically justify theism and argue against Shankara for real and eternal distinctions between God and individuals and between brahman and God, while at the same time maintaining the ultimate unity of brahman? In other words, he must affirm both the ultimate unity of brahman and the plurality of the attributes which define God and the soul Neither unity nor plurality may be allowed ultimacy at the expense of the other. Both must be shown to be ultimate.

Ramanuja attempted to do this through his notion of the inseparability (aprthak-siddhi) of substance and attribute. He argued that brahman, the one material cause, necessarily manifests itself as attributes equally real and eternally distinct from itself. As manifestations of brahman, however, they are inseparable from it. At the very heart of Ramanuja’s conception of brahman, according to Lacombe, is the notion that brahman’s very essence is to "complete" itself, or "overflow," or "produce" attributes:

If therefore it is legitimate . . . to emphasize that the demand . . . to be complete or to overflow in attributes which are the necessary expressions of its being, is at the same time a demand of distinction in terms of these same attributes, it is suitable to correct this abstraction by forcefully pointing out that this essence is a substance the fertility of which produces these attributes and in the functional identity of which the latter always remain. (10:290)

Thus the one brahman is only itself as it is also the many attributes including those which define God and the soul. The notion of brahman necessarily overflowing in attributes solved the problem of relating the one and the many for Ramanuja, but later Advaitic philosophers lost little time in pointing out that Ramanuja’s system lacked any explanation for why or how brahman should do this.

Before proceeding to illustrate how the Whiteheadian solution to this problem parallels the Indian, it should be pointed out that an answer to the larger question of the relation of brahman to creativity as process or becoming emerged. Ramanuja was able adequately to relate the one and the many only by conceiving of brahman as essentially dynamic. The terms "overflowing," "producing," and "completing" were used. Thus, here is one point where the description of brahman by the Indian tradition clearly parallels the very dynamic notion of creativity as becoming.

Returning to the question of the one and the many, according to Whitehead, "the many become one and are increased by one" (PR 32). In this solution to the problem of their relation, the movement from plurality to unity and renewed plurality is creativity. "It is that ultimate principle by which the many, which arc the universe disjunctively, become the one actual occasion. which is the universe conjunctively" (PR 31). Because of the epochal theory of time, this coalescence of the universe into a new unity is not temporally extensive. Therefore, the unification of the past world of actual entities occurs simultaneously with the reestablishment of plurality through the sudden emergence of a new actual entity. In this way unity and plurality share equal ultimacy in the dialectical movement of creativity from disjunction to conjunction. Thus, the one and the many are adequately interrelated and grounded in creativity. The analogy with Ramanuja’s attempt to do the same with brahman should be obvious.

Associated with this parallel between brahman and creativity concerning the one and the many, there is still another similarity between the thought of Ramanuja and Whitehead on the relation of substance and attribute. We have just seen how Ramanuja insisted on the inseparability of substance and attributes. It also should be emphasized that there is a relation of interdependence between them. Substance produces attributes but it does so necessarily and is therefore itself dependent on them. Lacombe explains, "if it is true that the substance produces at the interior of itself its own attributes, it does so because of necessities of its essence, which want to be expressed in a plurality of images of itself" (10:290). Thus brahman and the attributes which define God and the soul are interdependent and "co-ultimate." In a similar sense substance and attribute are also interdependent and "co-ultimate" within the Whiteheadian scheme. There can be no actual entities or attributes without creativity or substance because creativity is the very substance or material cause of actual entities. On the other hand, there can be no creativity without actual entities because creativity is the interaction of actual entities. In this way the two are interdependent. They are also co-ultimate. Creativity is the material cause of the universe while actual entities are the efficient causes. The latter are the building blocks of the world as we know it. They explain the "what" of reality. Creativity or substance explains the "that." Most importantly, however, there can be no "that" without a "what" and vice versa. The material cause and the efficient cause, substance and its accidents, are co-ultimate. Just as brahman was the key to understanding these relations of interdependence and co-ultimacy for Ramanuja, creativity plays the same role in the Whiteheadian scheme.

We have now compared creativity and the cosmic conception of brahman in the Upanishads in terms of space, time, causality, consciousness, and particulars. They have also been analyzed in relation to the concept of being itself. This led to a comparison of Ramanuja’s and Whitehead’s solutions to the problems of the one and the many, substance and attribute, and the role of becoming. The similarities in their descriptions are so many and so exact that one is naturally led to conclude that we are dealing here with one ultimate. Brahman and creativity may be said to be similar descriptions of one ultimate, independently arrived at in two very different cultural traditions. The question which now must be addressed is whether the same can be said of the characterizations of God in the two traditions.

On the relation of the conceptions of God in Western process philosophy and Indian philosophy, Charles Hartshorne has already pointed to the possibility of parallels. Speaking on the dominance of monism and the constant emphasis on the divine as substance in the Indian tradition, he commented: "thank in no small part to Ramanuja, a healthy instability does obtain and now and then results in approaches to dipolarism or panentheism" (PSG 178). We shall now argue that a great deal more than mere approaches to panentheism can be found in the Indian tradition.

One of the most interesting analogies between these two conceptions of God concerns the notion of Isvara as inner controller and God as the source of the initial aim. The notion of God as inner controller begins to play an important role in Indian theism in the Svetasvatara Upanishad. It is in that Upanishad which we have the only clearly identifiable instances. of Upanishadic theism. God is described as the "Inner Soul of all things" (Svet VI. 11; 1. 12) and as the inner guide running through all things like a thread (sutra) holding them together. The same concept has become a dominant element in the Gita’s presentation of the lord. Krishna teaches that he is in the very heart of all contingent kings, guiding and directing them. At times this direction is described in extremely forceful language. "In the region of the heart of all contingent beings dwells the Lord, twirling them hither and thither by his uncanny power (like puppets] mounted on a machine" (XVIII. 61).18 At other times the emphasis is only on supervision (X. 20; XV. 15; XIII. 17). Most often, this control is described through the metaphor of a seed. God controls all kings as the seed directs the future growth of a plant: "And what is the seed of all contingent beings, that too am I. No being is there, whether moving or unmoving, that exists or could exist apart from me" (X. 39; cf. VIII. 10; XIV. 3; XV. 7-10). Ramanuja used the body-soul metaphor to indicate the sense in which God is the inner director of all things. He guides persons and objects from within as the soul directs the body (see 1:399).

In the Whiteheadian system, God directs the development of an actual entity in the sense of luring it towards a form of self-realization productive of the greatest possible future intensity of feeling. This is done through the provision of a complex eternal object from the primordial nature of God (PR 374). Received through a hybrid physical feeling of God, it serves as an ideal for the concrescing actual entity in its self-development. This complex eternal object is a graded ordering of all possibilities for the new occasion as it creates itself through the process of decision (PR 374.75, 195, 373). Thus an ideal is given to lure the actual entity. There is no external constraint. The metaphor of a seed pregnant with possibilities for the growth and development of a new plant is not inappropriate for this provision of a guiding aim. There is clearly a likeness in these two descriptions of God’s way of working in the world.

Related to this parallel between these two conceptions is their further similarity in terms of God’s roles as creator and preserver. The Svetasvatara Upanishad refers to God as creator and sustainer (III. 2; IV IA; VI. 1 ff.) as does the Gita. God is creator in his capacity of spinning out nature: "By Me, Unmanifest in form, all this universe was spun" (IX. 4; cf. VIII. 22; XVIII. 46; I. 17). The idea of spinning out nature comes from the Sankhya concept of the evolution of the world out of nature (prakriti). Krishna teaches, "Subduing my own material Nature ever again I emanate this whole host of beings, -- powerless [themselves], from Nature comes the power" (IX. 8; cf. VII 4-5). Creation is also described as God’s planting of his seed: "Great Brahman is to Me a womb, in it I plant the seed: from this derives the origin of all contingent beings" (XIV. 3). The two accounts of creation are then reconciled in the Gita by the fact that brahman is understood to be composed of purusha and prakriti. In this way the planting of a seed in brahman is not unrelated to the spinning out of reality from nature (prakriti). According to the Gita, God is also the sustainer of the world (XV. 13). He is the sustainer in the sense that all reality is contingent with respect to him. Not only does reality depend on God for its initial existence, but it is dependent upon him for its continued existence: ‘No being is there, whether moving or unmoving, that exists or could exist apart from Me" (X. 39; cf. IX. 4-6, X 8). As all reality is dependent on God for its existence, the power of destruction also rests with God. God destroys the world at the end of each cosmic cycle by absorbing it into himself. It then evolves again out of God at the next period of creation. Krishna explains, "All contingent beings pour into material Nature which is mine when a world-aeon comes to an end; and then again when (another] aeon starts. I emanate them forth" (IX. 7). God is thus not only the origin but also the dissolution of all things (VII. 6 and IX. 18).

According to Ramanuja, matter and souls are modes of brahman. the material cause. They alternatively exist in two states: manifest and unmanifest (see 13: XXVIII). The unmanifest (pralaya) state is a subtle state in which particulars a-re not distinguished and in which matter is unevolved. Individual souls are not joined to material bodies and their intelligence is in a state of contraction. Creation marks the termination of this stage. Then, through an act of the lord’s will; matter becomes visible, tangible, and the selves become associated with bodies. Brahman is said to be the material cause and God the efficient cause in this creation.

For Whitehead too, God is creator in the sense of efficient cause. According to the ontological principle, only actual entities can be efficient or final causes. God is the efficient cause of all other actual entities in that he determines their locus within the extensive continuum and then provides them with a suitable aim. Without some aim they could not be, and without a particular aim they would not be what they are. It must be remembered, however, that God does not absolutely direct occasions, but rather "lures" them. God’s role as creator does not imply absolute control. Additionally, creation does not imply an initial temporal creation out of nothing: "God is not before all creation, but with all creation" (PR 521). Like the Indian notion rather than the Christian, creation for Whitehead merges into the conception of preservation. God is creator in the sense of continually providing initial aims for new actual entities. Creation is not once but always. In a sense, the entire cosmic process depends on him and the question arises of whether he or creativity is more ultimate in these causal terms. In any case, God -- like the Indian notion of Isvara -- can dearly be thought of as creator and preserver. Both continually operatC as efficient causes.

Probably the most arresting parallel between these two conceptions of God concerns the two ways in which the Indian notion approximates the Whiteheadian idea of panentheism. The first way has reference to God and actuality, the second to God and the universal According to the Whiteheadian characterization of God, all actual entities are absorbed in God’s consequent nature (PR 523). They are absorbed in the sense that God, like all actual entities, prehends all past occasions into his own actuality. As the one nontemporal actual entity, however, God never becomes objectively immortal. Therefore, unlike other actual entities, he will everlastingly draw actual entities Into himself (PR 524-25). In fact, God may be said to absorb the whole universe of actual entities into himself. The rough Indian analogy to this is the notion of Isvara as destroyer or absorber of the world. As absorbed in God, the world is in an unmanifest (pralaya) state. During this state, it was seen that particulars are not distinguished by name and form, matter is unevolved, and the intelligence of souls is contracted.

Beyond this vague analogy between Indian theism and the Whiteheadian conception of God, there is a larger and more profound sense in which the two types of panentheism are alike. This involves the rapport, not between God and actuality, but between God and the universal. There is a striking resemblance between the way brahman is related to Isvara and the way creativity is related to God. In the history of Indian thought the problem of relating Brahman and God was the central problem of the Bhagavad Gita. The Gita’s solution was to relate them, as well as the Sankhya absolutes of prakriti and purusha, through the conception of panentheism. The inclusion of prakriti and purusha was necessary due to the early contact of the Bhagavatas with the emerging system of Sankhya-Yoga thought. Brahman was first said to be composed of prakriti and purusha. In this way the primary categories of Sankhya-Yoga were reconciled with the absolute of Midland brahmanism. The latter was then in turn related to Vishnu-Vasudeva by conceiving of it as a portion of Isvara’s being. In this sense brahman is within Isvara. This becomes apparent in the following important passages:

Know too that [all] states of being whether they be of [Nature’s constituent] Goodness, Passion, or Darkness proceed from Me; but I am not in them, they are in Me. (VII 12)

By me, Unmanifest in form, all this universe was spun; in Me subsist all beings. I do not subsist in them. (IX. 4)

And why should they not revere You, great [as is your] Self, more to be prized even than Brahman, first creator, Infinite, Lord of gods, home of the universe? You are the Imperishable, what is what is not and what surpasses both. (XI. 37)

The only way that nature and brahman can be in God while God is not in them, but surpasses both, is for God to include brahman and the world within himself as a part of the whole. This is the Gita’s conception of panentheism. It is the key to understanding its metaphysics and ethics. Long ago, Edgerton noted that the Gita’s theism "differs from pantheism . . . in that it regards God as more than the universe" (4:149). Ramanuja too recognizes and affirms this form of panentheism in the Gita (14:139). God includes the universe and the imperishable brahman within himself, but that is only one part of the whole. The other part is beyond this part yet supports it: "This whole universe I hold apart [supporting it] with [but] one fragment [of Myself], yet I abide [unchanging]" (X.42). At times brahman is said to be the body of God or his womb out of which he creates. Again it is referred to as his highest home. R. C. Zaehner has interpreted the last characterization as meaning that brahman is God’s mode of being (15:185). In any case, all such characterizations indicate the nature of brahman as a portion of the lord.

In a similar way for the philosophy of organism, God and creativity are related in terms of panentheism. Also, creativity might be said to be God’s mode of being. As an actual entity, God is an instance of creativity -- the universal substance and material cause. He is described as being "in the grip of the ultimate metaphysical ground" and as the "primordial, nontemporal accident" of creativity (PR 529, II). As actual, God includes creativity within himself and could be said to have it as his body or mode of being. The parallel with Isvara should be apparent. Beyond this, however, it should also be pointed out that God is the one nontemporal actual entity. He is everlastingly actual. More specifically, his primordial nature is eternal and his consequent nature everlasting. This nontemporality and consequent everlastingness is analogous to the fact that, at the periods of cosmic absorption according to Ramanuja, the attributes which constitute God are not assimilated like the others. For both systems God as efficient cause must remain actual. Isvara himself never passes into the pralaya state and Whitehead’s God never becomes objectively immortal. Just as Isvara everlastingly reabsorbs the world but not the particulars of himself, so Whitehead’s God everlastingly prehends individual actual entities into his consequent nature. The similarity is clear. Yet, Ramanuja seems to suggest that one way in which Isvara also includes the totality of brahman as his body lies in the fact that he absorbs the world into the pralaya state. Having rejected any form of pantheism, Whitehead avoids this. God includes all actual entities within himself only as prehended objects (See IWM 403-9). He is therefore related to the whole of creativity somewhat differently. He may be said to include the totality of creativity only in the sense of everlastingly remaining an instance of it

The difference here is significant. While God and Isvara are identical in relation to the description of how the universal is related to each as its mode of being, so both conceptions of the divine affirm the notion that the world of particulars passes into God. Relatedly, both Ramanuja and Whitehead distinguish between those parts of the divine nature responsible for efficient and final causality. Yet they differ in the way that they understand how the totality of the universal is related to the divine. Certainly the closeness of the first two points of comparison and the similarity of intention concerning the third are sufficient to establish the parallel between these two related forms of panentheism. It might be noted that some contemporary process thinkers will probably find themselves more in agreement with Ramanuja than with Whitehead on this issue. If so, it remains to be seen which of these similar visions of panentheism is most adequate to the facts of experience and coherent in terms of total system.

The similarity of the cosmic conception of brahman and the notion of creativity has now been established. The parallel between the Indian view of Isvara and Whitehead’s vision of the divine has also become apparent. These facts serve as further evidence for the validity of these common conceptions from widely differing cultural contexts. They also suggest that Whitehead’s thought might provide the key element for an adequate bridge between Indian and Western philosophico-religious traditions. Lastly, in coherently and adequately relating God and creativity. Whitehead may have implicitly solved the age-old problem of Indian theists. Perhaps the bhakta’s problem of how best to understand Isvara and brahman may yet be resolved. Moreover, if this were done through the use of a system philosophically equal to that of Shankara, theism’s rightful claim to a place in the Indian tradition might again be clear. Certainly many questions still remain to be answered. For example, what might realization of creativity mean in Whiteheadian categories? Also, how might the interpretation of the mystic experience which produced the acosmic conception of brahman be explained from the Whiteheadian point of view? Answering these questions will be a very difficult task. Hopefully the material of the present study has suggested the possibility of genuine cross-cultural understanding through the use of the philosophy of organism. That, in turn, should provide ample motivation for the difficult tasks ahead.

References

IWM -- William A. Christian, An Interpretation of Whiteheads Metaphysics. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1959.

PSG -- Charles Hartshorne and William L. Reese, Philosophers Speak of God. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1953.

WA -- Donald W. Sherburne, A Whiteheadian Aesthetic. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1961.

WM -- Ivor Leclerc, Whitehead’s Metaphysics. London: George Allen & Unwin, 1958.

1. Surendranath Dasgupta. A History of Indian Philosophy. 5 volumes. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1963-1967.

2. Surendranath Dasgupta. Hindu Mysticism. Chicago: Open Court, 1927.

3. Paul Deussen. The Philosophy of the Upanishads. New York: Dover Publications. 1966.

4. Franklin Edgerton, ed. The Bhagavad Gita. New York: Harper and Row, 1944.

5. George A. Grierson. "Bhakti Marga" Encyclopedia of Religion and Ethics (1909). Volume II.

6. Charles Hartshorne. "Whitehead on Process: A Reply to Professor Eslick." Philosophy and Phenomenological Research XVIII (June, 1958).

7. M. Hiriyanna. Outlines of Indian Philosophy. London: George Allen and Unwin Ltd., 1932.

8. Robert Ernest Hume, ed. The Thirteen Principal Upanishads. Madras: Oxford University Press, 1951.

9. Arthur Berriedale Keith. The Religion and Philosophy of the Veda and Upanishads. Vol. XXXII, Harvard Oriental Series. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1925.

10. Olivier Lacombe. L’Absolu scIon Ic Vedanta. Paris: Librairie Orientaliste Paul Geuthner, 1966.

11. Rudolf Otto. India’s Religion of Giace and Cin-istianity Compared and Contrasted. New York: Macmillan Co.. 1930.

12. S. Radhakrishnan. Indian Philosophy. Volume I. New York: The Macmillan Co,. 1923.

13. George Thibaut. ed. The Vedanta-Sutras with Ramanuja’s Sribhashya. Sacred Books of the East. Volume XLVIII. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1904.

14. J. A. B. Van Buitenen, ed. Ramanuja on the Bhagavadgita. Delhi: Motilal Banarisdass, 1968.

15. R C. Zaehner, ed. The Bhagavad Gita. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1969

Notes

1 See: Max Miller. A History of Ancient Sanskrit Literature (London: Williams and Norgate, 1859), chapter IV and his Chips from a German Workshop (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons. 1900), Vol. 1, pp. 24-28; A. A. Macdonell, Vedic Mythology (Strassburg: Verlag Von Karl J. Tnbner, 1897), pp. 15-21; and 9:58ff.

2 References to the Rig Veda will appear as Rv. Upanishadic abbreviations are as follows:

Ait Aitareys Upanishad’

Brih Brihadaranyaka Upanishad

Chan . Chandogya Upanishad

Katha Katha Upanishad

Kaus Kaushitaki Upanishad

Mait. Maitri Upanishad

Svet. Svetagvatara Upanishad

All Upanishadic quotations are taken from 8.

3 See: I. B. Pratt. India and 1t~ Faiths (Boston: Houghton)Aiflhin Co., 1915), p. 76; 9:498: Washburn Hopkins. ‘The Religions of India (London: Ginn and Co., 1895), p. 220: M. Winternita, A History of Sanskrit Liu,-awre (Calcutta: University of Calcutta Press, 1927), Vol. 1, p 245; R. 0. Bhandarkar, Vaishn i~m, Sai,,ii,n. and Minor Religious Systems (Nepali Kapra, Varnas: Indological Book House, 1965), p. 1; j. N. Farquhar, ‘The Religious Quest of India: An Outline of the Religious Literature of India (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1920); George Thibaut, ed, ‘The VedantaSt.tra~ with the Co,nmeneary by Sanltarakaryo, p art I, Vol. XXXIV: Sacred Books of the Ea3r (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1890), ci if; H. O~d~nberg, Die Lehre Aer Upanishaden.snd die Anf~snge des Bicddhisnis (Gottingen: Vandenhoeck ~ Ruprecht, 1915). pp. 59-104; Miller, History of Sa,sskrit Literature. pp. 320 if; and 12:140. Often Upanishadic notions of brabman are miticized within the Upanishad themselves In Brih. II. I, twelve de~nitions of brahnsan are rejected; in Brib. IV. I. six: and in Kaus. IV. Sixteen

4 Hume consistently translates the Sanskrit term brahman (neuter) as Brabnia, the nominative single form. This should not be confused with Brahms, the name of a personal god of the Hindu trinity. In the text we have followed the more common usage -- brahman.

5For a more complete analysis of bhaj, and bhakti, see the work of M. Dhavamony, S.)., quoted in 15:181.