Interpreting Scripture as a Co-Creative Act

A Process-Existential Approach

Farhan Shah (Muslim philosopher)

Jay McDaniel (Christian theologian)

a companion to Beyond Rigidity: Iqbal, Whitehead, and a New Religious Existentialism

An existential approach to scripture recognizes that human beings, in their very existence, make decisions on how they live in the world and that, in so doing, they create their own futures. These decisions can be for good or ill. They can add beauty and love and justice to the world, or they can add greed and hatred and inequity to the world. Either way they are acts of creativity. When the acts produce beauty, kindness, and justice, they are co-creative with the very Soul of the universe, with God. Co-creativity is the act of cooperating with the Deep within the deep. With the Holy One.

Human decision-making includes an interpretation of scripture. It, too, can be an act of co-creativity. From a process perspective the interpretive process does not occur in isolation. It is influenced by a person’s culture, history, biography, and spiritual condition. If a person reads and interprets scripture with a heart of compassion, her reading will be constructive; if a person reads and interprets scripture with a heart of hatred, his reading will be destructive.

Of course this reading and interpretation rarely occurs in isolation. It is also shaped by community. We human beings are not islands unto ourselves; we are selves-in-community. They ways that we are shaped by communities and the ways that they shape us can likewise be constructive or destructive, Co-creativity can be communal as well as individual. Either way, interpretation can itself be a community process.

What an existentialist approach denies is that the scripture and its meanings are simply given to someone, apart from interpretation, which inevitably carries within it human limitations. This means that, as we interpret scripture, we must be humble, recognizing that our interpretation is not final or necessarily authoritative for all. It is the best we can come up, given the best of our lights. But we can also recognize, and celebrate, the fact that the interpretation is a creative process in its own right.

From a process perspective (Jewish, Christian or Muslim) this creativity is itself what is willed by the very heart of the universe, by the Holy One. The Holy One is not an autocrat jealous of the creativity of others, rather an all-merciful and compassionate reality by whose voice, as discerned in scripture and in the world, we humans are invited to be co-creators. Always the creativity must be loving. It must have the well-being of human beings in mind, sensitive to their dignity. But it is also free and imaginative, indeed joyful. The Holy One shares in that joy. Interpretation is a moral responsibility, true. And it is also a pleasure, for us and for the Holy One.

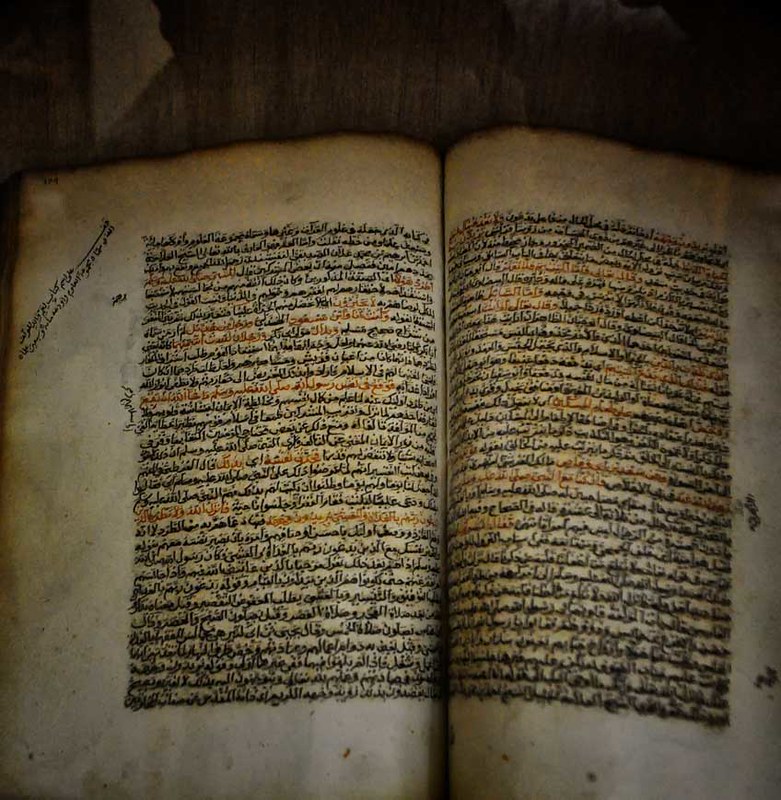

Of course, in interpreting scriptures, we humans must try to be faithful to the discernible meanings we find in scripture: in the Hebrew Bible, in the New Testament, in the Qur'an. The relation between interpreters and text is indeed a relation: that is, a dialogue. The interpreter has a voice and the text has a voice or, to be more accurate, many voices. The scriptures are multivalent, filled with many meanings: literal, allegorical, metaphorical, moral, and spiritual. With this in mind, Jews, Muslims, and Christian need not hide from the fact that an interpretation of scripture is a dialogue in which humans seek to discern the meanings in scripture most valuable to the common good of the world and most faithful to the divine source of life. The dialogue is never complete. There is never a moment when, in dialogue with a living scripture, someone says "Enough of this; we have reached a final conclusion; there are no more questions; all is clear!" The dialogue is ongoing, part of a people's relationship with a living text. We can celebrate the fact that interpretation is an ongoing dialogue that has no static end. The celebration, too, is an act of co-creativity.

Human decision-making includes an interpretation of scripture. It, too, can be an act of co-creativity. From a process perspective the interpretive process does not occur in isolation. It is influenced by a person’s culture, history, biography, and spiritual condition. If a person reads and interprets scripture with a heart of compassion, her reading will be constructive; if a person reads and interprets scripture with a heart of hatred, his reading will be destructive.

Of course this reading and interpretation rarely occurs in isolation. It is also shaped by community. We human beings are not islands unto ourselves; we are selves-in-community. They ways that we are shaped by communities and the ways that they shape us can likewise be constructive or destructive, Co-creativity can be communal as well as individual. Either way, interpretation can itself be a community process.

What an existentialist approach denies is that the scripture and its meanings are simply given to someone, apart from interpretation, which inevitably carries within it human limitations. This means that, as we interpret scripture, we must be humble, recognizing that our interpretation is not final or necessarily authoritative for all. It is the best we can come up, given the best of our lights. But we can also recognize, and celebrate, the fact that the interpretation is a creative process in its own right.

From a process perspective (Jewish, Christian or Muslim) this creativity is itself what is willed by the very heart of the universe, by the Holy One. The Holy One is not an autocrat jealous of the creativity of others, rather an all-merciful and compassionate reality by whose voice, as discerned in scripture and in the world, we humans are invited to be co-creators. Always the creativity must be loving. It must have the well-being of human beings in mind, sensitive to their dignity. But it is also free and imaginative, indeed joyful. The Holy One shares in that joy. Interpretation is a moral responsibility, true. And it is also a pleasure, for us and for the Holy One.

Of course, in interpreting scriptures, we humans must try to be faithful to the discernible meanings we find in scripture: in the Hebrew Bible, in the New Testament, in the Qur'an. The relation between interpreters and text is indeed a relation: that is, a dialogue. The interpreter has a voice and the text has a voice or, to be more accurate, many voices. The scriptures are multivalent, filled with many meanings: literal, allegorical, metaphorical, moral, and spiritual. With this in mind, Jews, Muslims, and Christian need not hide from the fact that an interpretation of scripture is a dialogue in which humans seek to discern the meanings in scripture most valuable to the common good of the world and most faithful to the divine source of life. The dialogue is never complete. There is never a moment when, in dialogue with a living scripture, someone says "Enough of this; we have reached a final conclusion; there are no more questions; all is clear!" The dialogue is ongoing, part of a people's relationship with a living text. We can celebrate the fact that interpretation is an ongoing dialogue that has no static end. The celebration, too, is an act of co-creativity.