"J" is for Justice

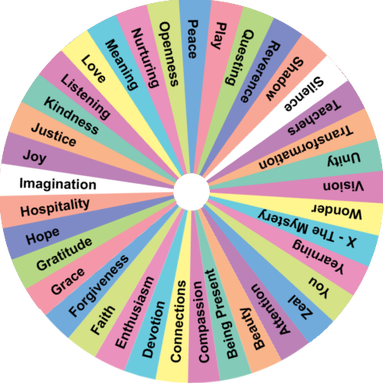

a reflection on Justice and its place in the Spiritual Alphabet

|

What is Justice Like?

Bread. A clean sky. Active peace. A woman's voice singing somewhere. The army disbanded. The harvest abundant. The wound healed. The child wanted. The prisoner freed. The body's integrity honored. The lover returned....Labor equal, fair and valued. No hand raised in gesture but greeting. Secure interiors -- of heart, home, and land -- so firm as to make secure borders irrelevant. -- Robin Morgan How do you Practice it?

This practice applies to the whole range of human interactions, and today it is also being extended to animals and the environment. It means that we deal fairly with others, recognizing the equality and dignity of all. It requires that we work to insure that all people, especially the poor and the weak, have access to opportunities. It assumes that none of us is free until all of us are...Practice justice by demanding it. Words can be as forceful as deeds — the prophets of old proved that. Name injustices when you see them. Speak boldly and put your body and your money where your mouth is. Stand up and be counted. -- Frederic and Mary Ann Brussat |

A Reflection on Justice and Spirituality

by Jay McDaniel

The spirituality behind justice is rich and vast. It includes compassion and reverence for life and a sense of connection and hope for a better world. Those who love justice -- those who seek fresh bread and a clean sky for all -- already know this. If you are among them, read no further. What needs to be said has been said above. But if you have doubts about connections between spirituality and justice, you might want to read a little further.

*

When I first encountered the spiritual alphabet of Mary Ann and Frederic Brussat, I looked for “J.” I expected to find "Joy" among the Js, but I wanted to see if "Justice" was included, and happily it was. I had Malcolm X and Martin Luther King, Jr. in mind. Also Kendrick Lamar and my friend Stan.

Stan is white and from Tennessee. I haven't seen him for years, but we were best friends in seminary. He pastored -- and perhaps still pastors -- an inner city, multi-racial church in Los Angeles, California. He was all about justice and not much about spirituality. His impression was that many people concerned with “spirituality” are middle-class, self-centered white people who are more interested in becoming whole as individuals than in helping heal a broken world. Here's how he would have put it:

There is too much “me’ in spirituality and not enough “we.’ Too much self-absorption and preoccupation with inner peace. The spiritually-preoccupied people I know hide from the world of social conflict and inequity in the interests of personal wholeness. They don't mind sitting in silent meditation or singing Kumbaya, but they are scared to death of turning over tables in a temple, or rattling the walls of city hall. Their god is being peaceful and being nice.

Stan loved the Bible, but he identified with the prophets of the Bible more than with the priests. He felt at home with the anger of Jeremiah, for example, and the anger of Jesus when he turned over the tables in the temple. What Stan missed in talk about spirituality was a willingness to engage in conflict and confrontation. To be angry like Jesus, and to turn over tables.

*

When I first encountered the spiritual alphabet of Mary Ann and Frederic Brussat, I looked for “J.” I expected to find "Joy" among the Js, but I wanted to see if "Justice" was included, and happily it was. I had Malcolm X and Martin Luther King, Jr. in mind. Also Kendrick Lamar and my friend Stan.

Stan is white and from Tennessee. I haven't seen him for years, but we were best friends in seminary. He pastored -- and perhaps still pastors -- an inner city, multi-racial church in Los Angeles, California. He was all about justice and not much about spirituality. His impression was that many people concerned with “spirituality” are middle-class, self-centered white people who are more interested in becoming whole as individuals than in helping heal a broken world. Here's how he would have put it:

There is too much “me’ in spirituality and not enough “we.’ Too much self-absorption and preoccupation with inner peace. The spiritually-preoccupied people I know hide from the world of social conflict and inequity in the interests of personal wholeness. They don't mind sitting in silent meditation or singing Kumbaya, but they are scared to death of turning over tables in a temple, or rattling the walls of city hall. Their god is being peaceful and being nice.

Stan loved the Bible, but he identified with the prophets of the Bible more than with the priests. He felt at home with the anger of Jeremiah, for example, and the anger of Jesus when he turned over the tables in the temple. What Stan missed in talk about spirituality was a willingness to engage in conflict and confrontation. To be angry like Jesus, and to turn over tables.

"S" and "T" and "H"

I am challenged by Stan because his critique applies to me. I like to be nice and peaceful. I'm pretty sure I make a god of them. His very critique is an invitation -- no, a demand -- that I confront my own shadow: that side of me which flees conflict and which enjoys the benefits of being white, middle-class, and comfortable, with a supportive family, health insurance, warmth from the cold, and enough money to pay the rent. A side of me which too often fails to acknowledge I am sheltered in ways that so many others are not.

Given Stan's critique, I find myself even more grateful that the alphabet includes not only "J" for justice, but also the practice of honesty about one's own sins: "S" is for Shadow. And I have to admit that, when I scroll through the spiritual alphabet, it can be easy to slide past Justice and Shadow in the interests, say, of silence or imagination or play or attention or beauty or joy. I want to consider things that sound “pleasant” or “enjoyable” or even "fun” -- but not things that smack of moral obligation and force me and others toward transformation. "T" is for transformation. And it is a mystery to me that I can also skip "H," which includes hospitality to the stranger. Maybe it's because, as a nice and peaceful person who is relatively kind on a one-on-one basis, I think I'm hospitable enough, forgetting that hospitality can and should include social hospitality and political hospitality: that is, making sure that all are taken care of, not just the people I happen to come across in my daily life.

Two Existential Questions: Loyalty and Fullness of Life

Stan had a great sense of humor. He knew "P" for play. And he loved to have a good time. He knew "Z" for zeal, or zest for life. He was a beer drinker par excellence. I liked to be around him even as he didn't quite appreciate my affinities for Buddhism. I was then, and am now, a Christian influenced by Buddhism. But he really wasn't much interested in the Buddhism that attracted me, including the Zen orientation of Thomas Merton. It seemed to him, well, kind of irrelevant to what is most important.

Moreover, when it came to religion, he couldn't quite understand where I was coming from, and I couldn't quite understand where he was coming from, with his unfettered desire for justice, and his appreciation of anger and table-overturning, because this had not been part of the Christianity I had known as a child. It was almost like we were asking, perhaps even driven by, different questions.

Recently I shared my confusion with my one of my own mentors, the well-known theologian John Cobb, and he suggested that different people can be pulled by two different questions which are complementary but which can be prioritized. Here they are:

I think that, when it comes to religion, the first question was Stan's and the second was mine. He saw religion primarily as a demand for hospitality to the stranger coming from God, with play and imagination and zest as important but secondary. I saw religion primarily as a lure toward the fullness of life, which includes, but is more than, hospitality to the stranger. I think we were both wrong, because both questions are equally important. And connected! I'd like to say a word about the loyalty question and how it leads to the fullness of life question.

To What Should I Be Loyal?

Many Christians I know will answer the first question -- To what should I be loyal? -- with the word “God.” Many religious Jews and Muslims will do the same. They will say that our first responsibility as human beings is to love God with all our hearts and then to love our neighbors as we love ourselves. Some among them will further imagine God as an authoritarian deity primarily concerned with reward and punishment and preoccupied with being flattered. Loyalty to God will be rooted in fear of punishment. Others will imagine God in more nurturing ways: as a loving presence who is gentle and graceful and inclusive, and who is then loved because God is so generous in spirit. Loyalty to God will be rooted in a sense of God's spacious and capacious love.

As process theologian I am in second camp, not the first. I believe that God is an encompassing love, embracing the whole universe, and affected by all that happens. I believe that God's deepest desire is not that "he" be flattered, but that we love our neighbors as ourselves, just as God loves them. And I believe that the universe itself is God’s body, which means that when we love others as we love ourselves, we are loving part of God. Our calling is not just to love those we find likeable or agreeable, but to love everyone and, for that matter, everything as best we can. God calls us to be Bodhisattvas: to postpone final nirvana until all living beings can join us.

All of this is to say that God's desire is that we enter into what Whitehead calls world loyalty: loyal to an inclusive whole that includes the world itself and the God who so loves it. The question: "To what should be be loyal?" is best answered by the response: "We should be loyal to the world that God so loves, because in being loyal to the world we are being loyal to God." The biblical traditions add that this world loyalty needs to include a special concern for the poor and powerless, the forsaken and forgotten, the vulnerable and despised. As Jesus emphasized, we are to love our enemies as well as our friends. World Loyalty is without walls and knows no boundaries. Needless to say, most of us fall short of such loyalty all the time. It is an ideal to be approximated, not a state of affairs to be fully claimed. Only God is World Loyalty to its fullest extent. But we are loyal to God to the degree and extent that we, too, are loyal to the world. Here "world" does not mean the human world alone. It means people, other animals, and the earth.

Practically speaking, we are loyal to the world in this way when we seek and work for the well-being of people and other living beings. And here is where the second question becomes so important: What possibilities for the fullness of life are available to us? If we seek the well-being of others, we want them to enjoy whatever range of richness of experience is possible for them, and we want to help eliminate any material, economic, and cultural structures that get in the way of that.

The Spiritual Alphabet as a Whole is Justice

The spiritual alphabet names many of these forms of richness. We want other people to enjoy opportunities for rich connections ("C" is for connection) and love ("L" is for love) and peace ("P" is for peace) and kindness ("K" is for kindness) and questing ("Q" is for questing) and self-affirmation ("Y" is for you) and a sheer exuberance for life ("Z" is for zeal). In short, the spiritual alphabet identifies what we seek for others and for ourselves, if we are loyal to the world. It names what we want and what God wants. We can use the word "Justice" to name the whole of the alphabet and not just the 'J." And it also offers a rubric for people like me to practice justice spiritually, not only by positive works, but also owning our own shadows and being open to transformation by others, especially those who are otherwise excluded from the benefits of social and economic life.

So, yes, let there be “J” for justice. And let it include "H" and "S" and "T" -- thereby helping people like me work toward communities where there is fresh bread, a clean sky, labor honored and no hand raised against others except in greeting.

The Word Justice

Now for a confession. Sometimes I do not like the word “justice.” In a biblical context it means right relationships among people (and let's add animals and the earth). That's fine. I think it's for four reasons: (1) rightly or wrongly, some people hear in the word an emphasis on retributive punishment; (2) some hear in the word a sharp division between us and them; (3) others hear in the word justice for humans alone, but not animals and the earth; and (4) still others use the word as an invitation to hate others. Like all words, the meaning of the word justice lies in its use, and sometimes the way the word "justice" is used is problematic.

Among my conservative friends the word usually evokes ideas of retribution, as when we say that people should get their just deserts. What that means is that people should be punished for their wrongdoings, not so that they might be rehabilitated, but because a moral balance needs to be restored. They need to suffer for what they’ve done.

Among my liberal friends the word evokes some things I think are more important. Justice means, for them, social justice. It means that we need to have societies where everyone’s voice is heard, where people participate in the decisions that affect their lives, where goods and services are distributed equitably, without obscene gaps between rich and poor, where individual rights are respected (including rights of self-expression, gender-identification, sexual orientation, and religious or non-religious affiliation). I like this kind of justice myself.

Others extend this notion of justice to mean eco-justice. For them, the earth itself can and should be a beneficiary of justice. This means, among other things, that other creatures need to have habitats where they can flourish and that individual animals within human communities (animals raised for food, for example) need to be treated humanely. Advocates of eco-justice also recognize that, when it comes to environmental degradation and global climate change, the human poor are often the first to suffer. We place pollution-creating factories in their backyards, not our own.

So, yes, I guess I’m on the liberal side here. I think social justice and eco-justice and justice for animals are really important. Still there are problems:

Sometimes, as we advocate these forms of justice, we end up creating hardened binaries between “us” and “them,” such that our worlds are divided into two categories: we self-righteous justice-lovers and the others who miss the mark. The enemies of the justice we advocate become just that: “enemies.” We end up objectifying them, denying them their humanity, all in the name of our high ideals. We then justify our rancor in the name of “righteous indignation.” We tell ourselves that we are “right” to feel such rancor and perhaps also that it is God’s will. We forget that we ourselves contain the inner impulses, if not also the actions, that we condemn in others. We forget to own our own shadows, to use the language of the spiritual alphabet.

So I close these remarks with the simple suggestion: let's not make a god of the word "justice." Sometimes it works, sometimes it doesn't. If there's a better word to make a god of, I suggest Love. Not the namby-pamby love that hides from the problems of the world in a safe haven of sentimentality, but the powerful love that reaches out, without hating anybody, to help heal a broken world, making it hospitable for all. Of course making a god of any word, including Love, is idolatry. But some idolatries are better than others and, after all, God is Love.

I am challenged by Stan because his critique applies to me. I like to be nice and peaceful. I'm pretty sure I make a god of them. His very critique is an invitation -- no, a demand -- that I confront my own shadow: that side of me which flees conflict and which enjoys the benefits of being white, middle-class, and comfortable, with a supportive family, health insurance, warmth from the cold, and enough money to pay the rent. A side of me which too often fails to acknowledge I am sheltered in ways that so many others are not.

Given Stan's critique, I find myself even more grateful that the alphabet includes not only "J" for justice, but also the practice of honesty about one's own sins: "S" is for Shadow. And I have to admit that, when I scroll through the spiritual alphabet, it can be easy to slide past Justice and Shadow in the interests, say, of silence or imagination or play or attention or beauty or joy. I want to consider things that sound “pleasant” or “enjoyable” or even "fun” -- but not things that smack of moral obligation and force me and others toward transformation. "T" is for transformation. And it is a mystery to me that I can also skip "H," which includes hospitality to the stranger. Maybe it's because, as a nice and peaceful person who is relatively kind on a one-on-one basis, I think I'm hospitable enough, forgetting that hospitality can and should include social hospitality and political hospitality: that is, making sure that all are taken care of, not just the people I happen to come across in my daily life.

Two Existential Questions: Loyalty and Fullness of Life

Stan had a great sense of humor. He knew "P" for play. And he loved to have a good time. He knew "Z" for zeal, or zest for life. He was a beer drinker par excellence. I liked to be around him even as he didn't quite appreciate my affinities for Buddhism. I was then, and am now, a Christian influenced by Buddhism. But he really wasn't much interested in the Buddhism that attracted me, including the Zen orientation of Thomas Merton. It seemed to him, well, kind of irrelevant to what is most important.

Moreover, when it came to religion, he couldn't quite understand where I was coming from, and I couldn't quite understand where he was coming from, with his unfettered desire for justice, and his appreciation of anger and table-overturning, because this had not been part of the Christianity I had known as a child. It was almost like we were asking, perhaps even driven by, different questions.

Recently I shared my confusion with my one of my own mentors, the well-known theologian John Cobb, and he suggested that different people can be pulled by two different questions which are complementary but which can be prioritized. Here they are:

- The Loyalty Question: To what should I be loyal? What am I called to do with my life? For what am I responsible?

- The Fullness of Life Question: What possibilities for the fullness of life are available to me and others? How might we become more whole?

I think that, when it comes to religion, the first question was Stan's and the second was mine. He saw religion primarily as a demand for hospitality to the stranger coming from God, with play and imagination and zest as important but secondary. I saw religion primarily as a lure toward the fullness of life, which includes, but is more than, hospitality to the stranger. I think we were both wrong, because both questions are equally important. And connected! I'd like to say a word about the loyalty question and how it leads to the fullness of life question.

To What Should I Be Loyal?

Many Christians I know will answer the first question -- To what should I be loyal? -- with the word “God.” Many religious Jews and Muslims will do the same. They will say that our first responsibility as human beings is to love God with all our hearts and then to love our neighbors as we love ourselves. Some among them will further imagine God as an authoritarian deity primarily concerned with reward and punishment and preoccupied with being flattered. Loyalty to God will be rooted in fear of punishment. Others will imagine God in more nurturing ways: as a loving presence who is gentle and graceful and inclusive, and who is then loved because God is so generous in spirit. Loyalty to God will be rooted in a sense of God's spacious and capacious love.

As process theologian I am in second camp, not the first. I believe that God is an encompassing love, embracing the whole universe, and affected by all that happens. I believe that God's deepest desire is not that "he" be flattered, but that we love our neighbors as ourselves, just as God loves them. And I believe that the universe itself is God’s body, which means that when we love others as we love ourselves, we are loving part of God. Our calling is not just to love those we find likeable or agreeable, but to love everyone and, for that matter, everything as best we can. God calls us to be Bodhisattvas: to postpone final nirvana until all living beings can join us.

All of this is to say that God's desire is that we enter into what Whitehead calls world loyalty: loyal to an inclusive whole that includes the world itself and the God who so loves it. The question: "To what should be be loyal?" is best answered by the response: "We should be loyal to the world that God so loves, because in being loyal to the world we are being loyal to God." The biblical traditions add that this world loyalty needs to include a special concern for the poor and powerless, the forsaken and forgotten, the vulnerable and despised. As Jesus emphasized, we are to love our enemies as well as our friends. World Loyalty is without walls and knows no boundaries. Needless to say, most of us fall short of such loyalty all the time. It is an ideal to be approximated, not a state of affairs to be fully claimed. Only God is World Loyalty to its fullest extent. But we are loyal to God to the degree and extent that we, too, are loyal to the world. Here "world" does not mean the human world alone. It means people, other animals, and the earth.

Practically speaking, we are loyal to the world in this way when we seek and work for the well-being of people and other living beings. And here is where the second question becomes so important: What possibilities for the fullness of life are available to us? If we seek the well-being of others, we want them to enjoy whatever range of richness of experience is possible for them, and we want to help eliminate any material, economic, and cultural structures that get in the way of that.

The Spiritual Alphabet as a Whole is Justice

The spiritual alphabet names many of these forms of richness. We want other people to enjoy opportunities for rich connections ("C" is for connection) and love ("L" is for love) and peace ("P" is for peace) and kindness ("K" is for kindness) and questing ("Q" is for questing) and self-affirmation ("Y" is for you) and a sheer exuberance for life ("Z" is for zeal). In short, the spiritual alphabet identifies what we seek for others and for ourselves, if we are loyal to the world. It names what we want and what God wants. We can use the word "Justice" to name the whole of the alphabet and not just the 'J." And it also offers a rubric for people like me to practice justice spiritually, not only by positive works, but also owning our own shadows and being open to transformation by others, especially those who are otherwise excluded from the benefits of social and economic life.

So, yes, let there be “J” for justice. And let it include "H" and "S" and "T" -- thereby helping people like me work toward communities where there is fresh bread, a clean sky, labor honored and no hand raised against others except in greeting.

The Word Justice

Now for a confession. Sometimes I do not like the word “justice.” In a biblical context it means right relationships among people (and let's add animals and the earth). That's fine. I think it's for four reasons: (1) rightly or wrongly, some people hear in the word an emphasis on retributive punishment; (2) some hear in the word a sharp division between us and them; (3) others hear in the word justice for humans alone, but not animals and the earth; and (4) still others use the word as an invitation to hate others. Like all words, the meaning of the word justice lies in its use, and sometimes the way the word "justice" is used is problematic.

Among my conservative friends the word usually evokes ideas of retribution, as when we say that people should get their just deserts. What that means is that people should be punished for their wrongdoings, not so that they might be rehabilitated, but because a moral balance needs to be restored. They need to suffer for what they’ve done.

Among my liberal friends the word evokes some things I think are more important. Justice means, for them, social justice. It means that we need to have societies where everyone’s voice is heard, where people participate in the decisions that affect their lives, where goods and services are distributed equitably, without obscene gaps between rich and poor, where individual rights are respected (including rights of self-expression, gender-identification, sexual orientation, and religious or non-religious affiliation). I like this kind of justice myself.

Others extend this notion of justice to mean eco-justice. For them, the earth itself can and should be a beneficiary of justice. This means, among other things, that other creatures need to have habitats where they can flourish and that individual animals within human communities (animals raised for food, for example) need to be treated humanely. Advocates of eco-justice also recognize that, when it comes to environmental degradation and global climate change, the human poor are often the first to suffer. We place pollution-creating factories in their backyards, not our own.

So, yes, I guess I’m on the liberal side here. I think social justice and eco-justice and justice for animals are really important. Still there are problems:

Sometimes, as we advocate these forms of justice, we end up creating hardened binaries between “us” and “them,” such that our worlds are divided into two categories: we self-righteous justice-lovers and the others who miss the mark. The enemies of the justice we advocate become just that: “enemies.” We end up objectifying them, denying them their humanity, all in the name of our high ideals. We then justify our rancor in the name of “righteous indignation.” We tell ourselves that we are “right” to feel such rancor and perhaps also that it is God’s will. We forget that we ourselves contain the inner impulses, if not also the actions, that we condemn in others. We forget to own our own shadows, to use the language of the spiritual alphabet.

So I close these remarks with the simple suggestion: let's not make a god of the word "justice." Sometimes it works, sometimes it doesn't. If there's a better word to make a god of, I suggest Love. Not the namby-pamby love that hides from the problems of the world in a safe haven of sentimentality, but the powerful love that reaches out, without hating anybody, to help heal a broken world, making it hospitable for all. Of course making a god of any word, including Love, is idolatry. But some idolatries are better than others and, after all, God is Love.