- Home

- Process Worldview

- Community

- Art and Music

- Whitehead and Process Thinking

- Podcasts

- Spirituality

- Ecological Civilization

- Education

- Contact

- Social Justice

- Science

- Animals

- Sacred Poems

- Whitehead Videos

- Index of All Titles

- Practicing Process Thought

- Process Spirituality: A Spiritual Alphabet

- Recent Posts

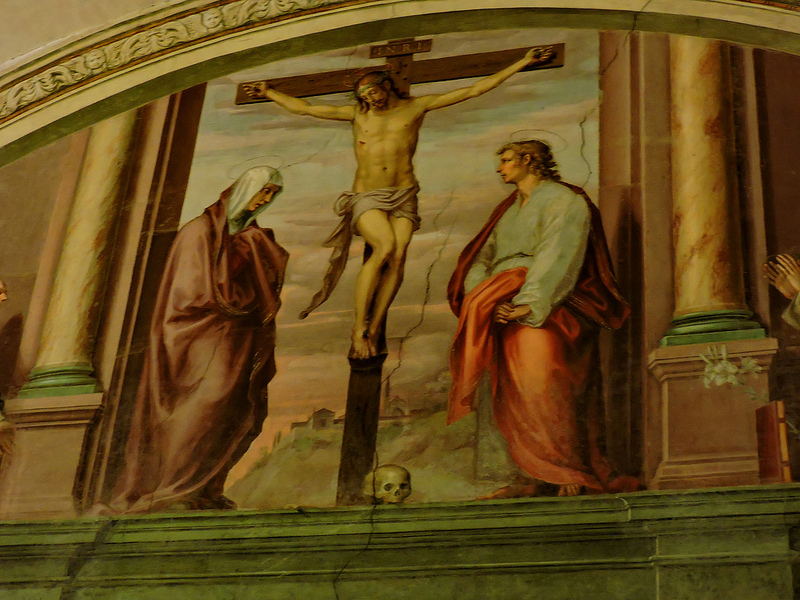

Jesus: A King Like None Other

A Sermon for Christ the King Sunday

by Teri Daily

|

I attended Duke University as an undergraduate. Since my major was zoology and I was pre-med, I spent a lot of time in a part of campus called Science Drive. Huge buildings full of labs and lecture halls and offices stood side-by-side. There was the chemistry building, which was next to the biology building, which was next to the physics building – each discipline having its own defined space, its own sphere both geographically and as a field of study.

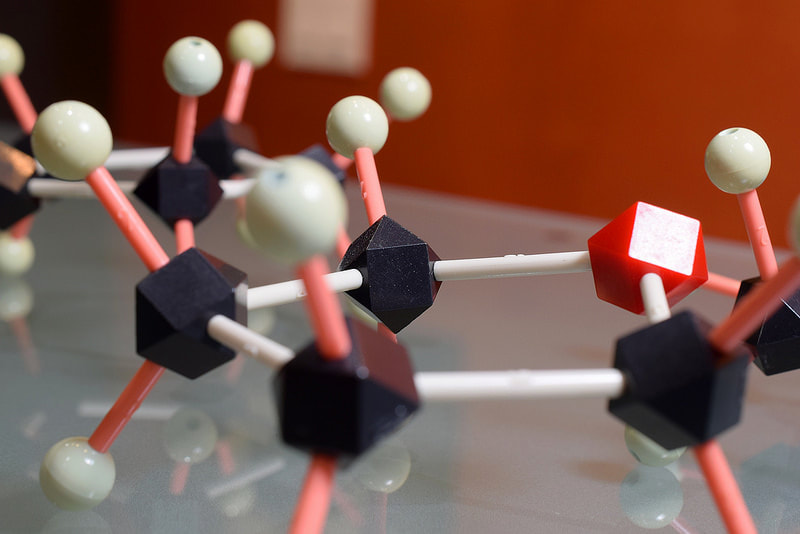

Chemistry deals with how substances interact with, and are transformed by, other substances and energy. This means that chemistry is the study of matter on the atomic and molecular level. Physics is concerned primarily with matter and its behavior in space and time; it explores the effects of gravitational and electromagnetic forces. The discipline of physics involves entities that range in size from a quark to a galaxy, and beyond. Biology is the area of science that examines living organisms – their structure, physiological processes, and evolution. These three areas – chemistry, physics, and biology – make up the natural sciences. The arrangement of science departments wherein each discipline is housed in a separate building may be out-of-date, because simple definitions for each area of study no longer hold. As our knowledge of science has progressed, the lines between the areas of study have become increasingly blurred. Biological organisms depend on the molecular structure of DNA with its chemical bonds to pass on information from one generation to another – biology and chemistry are not two completely different fields. Forces are in play at every level of biology, from the electromagnetic forces between individual atoms to the mechanical forces that affect the function of larger joints – the disciplines of physics and biology cannot be isolated one from the other. And the study of how light interacts with specific chemical substances involves a convergence of chemistry and physics. The truth is that the fields of the natural sciences are not like parallel lines leading out into infinity; instead, they intersect with one another in time and space and subject matter. The outdated arrangement of Science Drive with its separate buildings – its distinct domains – came to mind when I read today’s passage from the gospel of John. It is the day of Jesus’ crucifixion, and Jesus has been arrested and handed over to Pilate. “Are you the King of the Jews?” Pilate asks. Jesus goes on to reply: “My kingdom is not from this world. If my kingdom were from this world, my followers would be fighting to keep me from being handed over to the Jews. As it is, my kingdom is not from this world.” What do make of this answer? Is Jesus King of the Jews? Today, on the Christ the King Sunday, we go even further and ask the question: Is Jesus king of all that is? It’s a question of boundaries – boundaries that define space, time, and subject matter. When Jesus replies that his kingdom is not from this world, is he suggesting that his kingdom is unlike the world’s kingdom in its subject matter? Certainly it’s a different kingdom in how it operates. If Jesus’ kingdom operated like the kingdom of Caesar, his followers would fight; they would use violence to keep him from being handed over to the authorities. As it is, they stand by and bear witness. If Jesus’ kingdom operated like the kingdoms of this world, Jesus and his followers would contend for places of honor, influence, and power. As it is, they eat with tax collectors, heal lepers, and wash one another’s feet. If Jesus’ kingdom operated like the kingdoms of this world, Jesus and his followers would stick to geographic and ethnic boundaries. As it is, Jesus loves and respects every human being; he offers the Samaritan woman living water and heals the Syro-Phoenician woman’s daughter. Jesus’ kingdom operates in a very different way than the kingdom of Caesar, the kingdom to which Pilate belongs and under which first century Jews live. But when I ask about the subject matter of Jesus’ kingdom, my question is somewhat different from that of how his kingdom operates. Instead, I’m asking about the domain of its operation. Does it have its own building – a separate space where it is relevant apart from the kingdom of this world? I think we sometimes act as if it does. Our spiritual and religious life is private, we often think; it is something that takes place on Sundays and not on workdays, in our homes and not in public spaces. I’m reminded of a woman with whom I worshiped in Connecticut; her father said that he was fine with her being baptized, just as long as it did not change her beliefs, her politics, or the way she lived. That’s not the way Christianity works. Jesus reminds us over and over again in the gospel that we cannot serve two masters. We don’t get to separate our lives into one realm where Jesus is king and another realm where Caesar is king. Complete devotion to Christ will bleed over into every corner of our life. When Jesus replies that his kingdom is not from this world, is he then suggesting that his kingdom is for a different time and place? Does he mean that the kingdom of heaven is something that will happen in the future – in heaven? So many times we talk and act as if God’s reign is a distant dream – a future world where there will be peace, healing, and abundance, if only we can make our way through this earthly journey. There is a sense in which we wait for and hope for a day when God’s dream for the world will be fulfilled and Christ will be all in all. But every time we choose love over hate, peace over violence, plenty over scarcity, and reconciliation over division – we are acknowledging the reign of God in the here and now. The kingdom in which Jesus is king is not relegated to some different time and place. Many of us we are uncomfortable with the metaphor of Christ as king. We think either of earthly kings and dictators who rule by force or of those who are merely figureheads, irrelevant to the day-to-day functioning of their countries. Jesus is neither. Rowan Williams, former Archbishop of Canterbury, suggests that when we speak of Jesus as Lord of lords or as King of kings or as King of all, we are really saying that Jesus is present and relevant in every time and in every place – inviting us to be his hands, feet, head, and heart in the here and now. Even in the most difficult and dark places, Jesus is present “as a point of creative protest”– challenging us to grow and change.[1] In other words, there is no situation in which we cannot make the kingdom of God a reality. In each and every moment we have the opportunity to choose love over hate, peace over violence, a mindset of plenty over a mindset of scarcity, and reconciliation over division. Like the natural sciences on Science Drive, Jesus’ kingdom can’t be confined to a single building or a single domain; it is not limited by boundaries of time, space, or subject matter. It comes into play with each morsel of our existence – in every moment and every place, whenever and wherever we choose the kingdom of Jesus over the kingdom of any Caesar. [1] Rowan Williams, Truce of God (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2005) 30-31. |