- Home

- Process Worldview

- Community

- Art and Music

- Whitehead and Process Thinking

- Podcasts

- Spirituality

- Ecological Civilization

- Education

- Contact

- Social Justice

- Science

- Animals

- Sacred Poems

- Whitehead Videos

- Index of All Titles

- Practicing Process Thought

- Process Spirituality: A Spiritual Alphabet

- Recent Posts

UNESCO: Living Heritage and Sustainable Development:

The Reception and Recreation of Intangible Cultural Heritages in China

a Gift from UNESCO to Ecological Education

videos and descriptions from UNESCO

Explanation: A new kind of education is emerging in different parts of the world today. The Global Network of Ecological Education calls it "ecological education." Ecological education occurs in the classroom, at home, and in the local community. It does not separate the world into human beings and nature, but instead sees human beings as co-creators within, and part of, the larger web of life. And its aim is not only to protect the more than human world, the “environment,” it is also to help human beings flourish in their capacities for personal fulfillment and living together with respect and care. The aim of ecological education is to help build communities in rural and local settings that are creative, compassionate, paricipatory, humane to the animals, and good for the earth, with no one left behind.

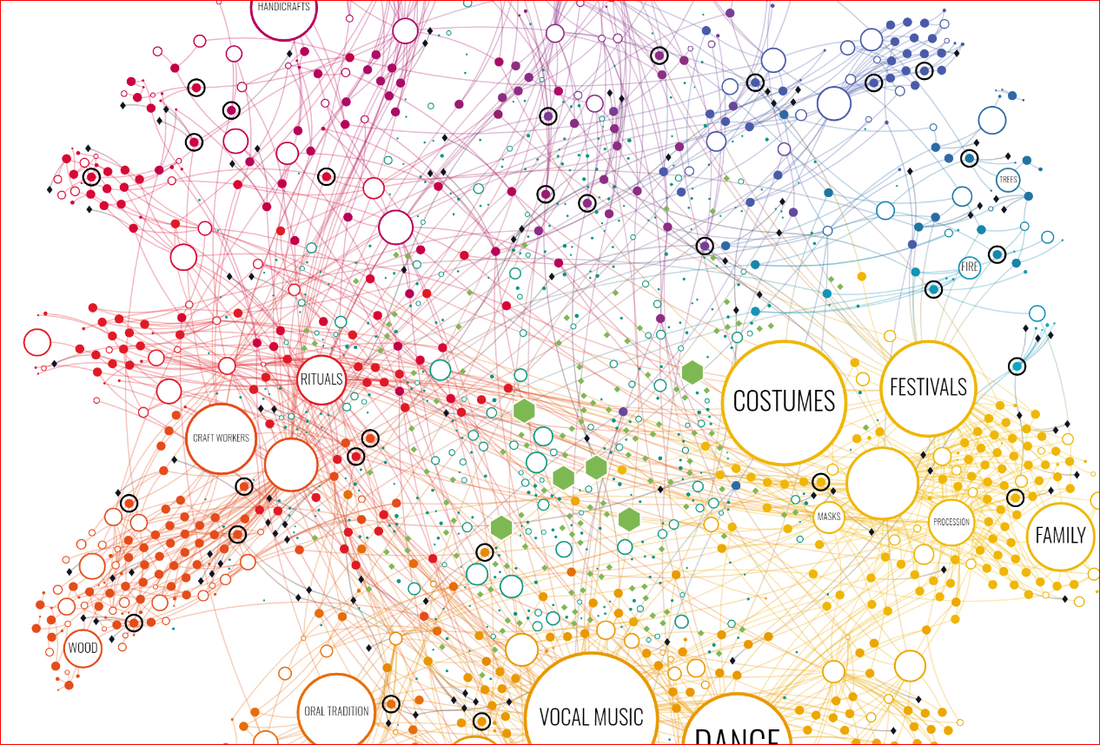

The creativity of sustainalbe communities includes the reception and recreation of intangible cultural heritages. “Intangible cultural heritages” are, in the words of UNESCO, "the practices, representations, expressions, knowledge, skills – as well as the instruments, objects, artefacts and cultural spaces associated therewith – that communities, groups and, in some cases, individuals recognize as part of their cultural heritage.

"This intangible cultural heritage, transmitted from generation to generation, is constantly recreated by communities and groups in response to their environment, their interaction with nature and their history, and provides them with a sense of identity and continuity, thus promoting respect for cultural diversity and human creativity."

The components of these heritages are traditional craftsmanship; oral traditions and expressions; performing arts; rituals and festive events; and knowledge and practices of nature and the universe. This page, featuring videos and descriptions offered by UNESCO, is to help people in different parts of the world learn about some of those heritages in China.

The creativity of sustainalbe communities includes the reception and recreation of intangible cultural heritages. “Intangible cultural heritages” are, in the words of UNESCO, "the practices, representations, expressions, knowledge, skills – as well as the instruments, objects, artefacts and cultural spaces associated therewith – that communities, groups and, in some cases, individuals recognize as part of their cultural heritage.

"This intangible cultural heritage, transmitted from generation to generation, is constantly recreated by communities and groups in response to their environment, their interaction with nature and their history, and provides them with a sense of identity and continuity, thus promoting respect for cultural diversity and human creativity."

The components of these heritages are traditional craftsmanship; oral traditions and expressions; performing arts; rituals and festive events; and knowledge and practices of nature and the universe. This page, featuring videos and descriptions offered by UNESCO, is to help people in different parts of the world learn about some of those heritages in China.

Living Cultures in China

Videos and Descriptions from UNESCO

TaijiquanDescription: Taijiquan is a traditional physical practice characterized by relaxed, circular movements in concert with breath regulation and cultivation of a righteous and neutral mind. Originating during the mid- seventeenth century in the Henan Province of central China, the element is now practised throughout the country by a wide array of people. Influenced by Daoist and Confucian thought and traditional Chinese medicine, the element has developed into several schools (or styles) named after a clan or a master’s personal name.

The Twenty-Four Solar Terms, through observation of the sun’s annual motion, in ChinaDescription: To better understand the seasons, astronomy and other natural phenomena the ancient Chinese looked at the sun’s circular motion and divided it into 24 segments called Solar Terms. The terms such as First Frost, based on observations of the environment, have been integrated in calendars as a timeframe for daily routines and production, being particularly important for farmers. Some folk festivities are associated with the terms, which have contributed to community cultural identity. Knowledge is transmitted in families and schools.

Chinese Shadow PuppetryDescription: Chinese shadow puppetry is a form of theatre whereby colourful silhouette figures perform traditional plays against a back-lit cloth screen, accompanied by music and singing. Puppeteers make the figures from leather or paper and manipulate them by means of rods to create the illusion of moving images. The puppeteers' skills of simultaneously manipulating several puppets, improvisational singing, and playing various musical instruments are handed down in families and troupes, passing from master to pupil. Puppetry spreads knowledge, promotes cultural values and entertains the community, especially the youth.

Manas: An EpicDescription: The Kirgiz ethnic minority in China, concentrated in the Xinjiang region in the west, pride themselves on their descent from the hero Manas, whose life and progeny are celebrated in one of the best-known elements of their oral tradition: the Manas epic. Traditionally sung by a Manaschi without musical accompaniment, epic performances takes place at social gatherings, community celebrations, ceremonies such as weddings and funerals and dedicated concerts. Regional variations abound, but all are characterized by pithy lyrics with phrases that now permeate the everyday language of the people, melodies adapted to the story and characters, and lively parables. The long epic records all the major historic events of greatest importance for the Kirgiz people and crystallizes their traditions and beliefs. The Kirgiz in China and the neighbouring Central Asian countries of Kyrgyzstan, Kazakhstan and Tajikistan regard the Manas as a key symbol of their cultural identity and the most important cultural form for public entertainment, the preservation of history, the transmission of knowledge to the young and the summoning of good fortune. One of the three major epics of China, it is both an outstanding artistic creation and an oral encyclopaedia of the Kirgiz people.

Hezhen Yimakan storytellingDescription: Narrated in the language of the Hezhen people of north-east China, and taking both verse and prose forms, Yimakan storytelling consists of many independent episodes depicting tribal alliances and battles, including the defeat of monsters and invaders by Hezhen heroes. Yimakan performers improvise stories without instrumental accompaniment, alternating between singing and speaking, and make use of different melodies to represent different characters and plots. Yimakan plays a key role in preserving the Hezhen mother tongue, religion, beliefs, folklore and customs.

Peking OperaDescription: Peking opera is a performance art incorporating singing, reciting, acting, martial arts. Although widely practised throughout China, its performance centres on Beijing, Tianjin and Shanghai. Peking opera is sung and recited using primarily Beijing dialect, and its librettos are composed according to a strict set of rules that prize form and rhyme. They tell stories of history, politics, society and daily life and aspire to inform as they entertain. The music of Peking opera plays a key role in setting the pace of the show, creating a particular atmosphere, shaping the characters, and guiding the progress of the stories. 'Civilian plays' emphasize string and wind instruments such as the thin, high-pitched ''jinghu ''and the flute ''dizi, ''while 'military plays' feature percussion instruments like the ''bangu ''or ''daluo. ''Performance is characterized by a formulaic and symbolic style with actors and actresses following established choreography for movements of hands, eyes, torsos, and feet. Traditionally, stage settings and props are kept to a minimum. Costumes are flamboyant and the exaggerated facial make-up uses concise symbols, colours and patterns to portray characters' personalities and social identities. Peking opera is transmitted largely through master-student training with trainees learning basic skills through oral instruction, observation and imitation. It is regarded as an expression of the aesthetic ideal of opera in traditional Chinese society and remains a widely recognized element of the country's cultural heritage.

Chinese Zhusuan, knowledge and practices of mathematical calculation through the abacusDescription: Chinese Zhusuan is a time-honoured traditional method of performing mathematical calculations with an abacus. By moving beads along rods, practitioners can perform addition, subtraction, multiplication, division, exponential multiplication, root and more complicated equations. Zhusuan has been handed down through the generations, using traditional models of oral teaching and self-learning. Beginners can make quick calculations after some fairly basic training, while proficient practitioners develop an agile mind. Zhusuan is widely used in Chinese life and is an important symbol of traditional Chinese culture and identity.

Traditional handicrafts of making Xuan paperDescription: The unique water quality and mild climate of Jing County in Anhui Province in eastern China are two of the key ingredients in the craft of making Xuan paper that thrives there. Handmade from the tough bark of the Tara Wing-Celtis or Blue Sandalwood tree and rice straw, Xuan paper is known for its strong, smooth surface, its ability to absorb water and moisten ink, and fold repeatedly without breaking. It has been widely used in calligraphy, painting and book printing. The traditional process passed down orally over generations and still followed today proceeds strictly by hand through more than a hundred steps such as steeping, washing, fermenting, bleaching, pulping, sunning and cutting all of which lasts more than two years. The production of the Paper of Ages or King of Papers is a major part of the economy in Jing County, where the industry directly or indirectly employs one in nine locals and the craft is taught in local schools. True mastery of the entire complicated process is won only by a lifetime of dedicated work. Xuan paper has become synonymous with the region, where a score of artisans still keep the craft alive.

|

Acupuncture and moxibustion of traditional Chinese medicineDescription: Acupuncture and moxibustion are forms of traditional Chinese medicine widely practised in China and also found in regions of south-east Asia, Europe and the Americas. The theories of acupuncture and moxibustion hold that the human body acts as a small universe connected by channels, and that by physically stimulating these channels the practitioner can promote the human body's self-regulating functions and bring health to the patient. This stimulation involves the burning of moxa (mugwort) or the insertion of needles into points on these channels, with the aim to restore the body's balance and prevent and treat disease. In acupuncture, needles are selected according to the individual condition and used to puncture and stimulate the chosen points. Moxibustion is usually divided into direct and indirect moxibustion, in which either moxa cones are placed directly on points or moxa sticks are held and kept at some distance from the body surface to warm the chosen area. Moxa cones and sticks are made of dried mugwort leaves. Acupuncture and moxibustion are taught through verbal instruction and demonstration, transmitted through master-disciple relations or through members of a clan. Currently, acupuncture and moxibustion are also transmitted through formal academic education.

Xian wind and percussionDescription: Xian wind and percussion ensemble, which has been played for more than a millennium in Chinas ancient capital of Xian, in Shaanxi Province, is a type of music integrating drums and wind instruments, sometimes with a male chorus. The content of the verses is mostly related to local life and religious belief and the music is mainly played on religious occasions such as temple fairs or funerals. The music can be divided into two categories, sitting music and walking music, with the latter also including the singing of the chorus. Marching drum music used to be performed on the emperors trips, but has now become the province of farmers and is played only in open fields in the countryside. The drum music band is composed of thirty to fifty members, including peasants, teachers, retired workers, students and others. The music has been transmitted from generation to generation through a strict master-apprentice mechanism. Scores of the music are recorded using an ancient notation system dating from the Tang and Song dynasties (seventh to thirteenth centuries). Approximately three thousand musical pieces are documented and about one hundred fifty volumes of handwritten scores are preserved and still in use. Country(ies): China © 2008 Shaanxi Art Research Institute

Lum medicinal bathing, knowledge concerning life among the Tibetan people in ChinaDescription: Lum Medicinal Bathing of Sowa Rigpa is a practice developed by the Tibetan people as part of a life view based on the five elements and a view of health and illness centred on three dynamics (Lung, Tripa and Pekan). In Tibetan, ‘Lum’ indicates the traditional knowledge and practices of bathing in natural hot springs, herbal water or steam to adjust the balance of the body and mind, ensure health and treat illness. The element plays a key role in improving health conditions and promoting respect for nature.

Chinese Engraved Block PrintingDescription: The traditional China engraved block printing technique requires the collaboration of half a dozen craftspeople possessed of printing expertise, dexterity and team spirit. The blocks themselves, made from the fine-grained wood of pear or jujube trees, are cut to a thickness of two centimetres and polished with sandpaper to prepare them for engraving. Drafts of the desired images are brushed onto extremely thin paper and scrutinized for errors before they are transferred onto blocks. The inked designs provide a guide for the artisan who cuts the picture or design into the wood, producing raised characters that will eventually apply ink to paper. First, though, the blocks are tested with red and then blue ink and corrections are made to the carving. Finally, when the block is ready to be used, it is covered with ink and pressed by hand onto paper to print the final image. Block engraving may be used to print books in a variety of traditional styles, to create modern books with conventional binding, or to reproduce ancient Chinese books. A number of printing workshops continue this handicraft today thanks to the knowledge and skills of the expert artisans.

The Guqin and its MusicDescription: The Chinese zither, called guqin, has existed for over 3,000 years and represents Chinas foremost solo musical instrument tradition. Described in early literary sources and corroborated by archaeological finds, this ancient instrument is inseparable from Chinese intellectual history. Guqin playing developed as an elite art form, practised by noblemen and scholars in intimate settings, and was therefore never intended for public performance. Furthermore, the guqin was one of the four arts along with calligraphy, painting and an ancient form of chess that Chinese scholars were expected to master. According to tradition, twenty years of training were required to attain proficiency. The guqin has seven strings and thirteen marked pitch positions. By attaching the strings in ten different ways, players can obtain a range of four octaves. The three basic playing techniques are known as san (open string), an (stopped string) and fan (harmonics). San is played with the right hand and involves plucking open strings individually or in groups to produce strong and clear sounds for important notes. To play fan, the fingers of the left hand touch the string lightly at positions determined by the inlaid markers, and the right hand plucks, producing a light floating overtone. An is also played with both hands: while the right hand plucks, a left-hand finger presses the string firmly and may slide to other notes or create a variety of ornaments and vibratos. Nowadays, there are fewer than one thousand well-trained guqin players and perhaps no more than fifty surviving masters. The original repertory of several thousand compositions has drastically dwindled to a mere hundred works that are regularly performed today.

Ong Chun/Wangchuan/Wangkang ceremony, rituals in China and MalaysiaDescription: The Ong Chun ceremony and related practices are rooted in folk customs of worshipping Ong Yah, a deity believed to protect people and their lands from disasters. The element is centered in coastal communities in China’s Minnan region and in Melaka, Malaysia. The ceremony includes welcoming Ong Yah to temples or clan halls, delivering 'good brothers' (people lost at sea) from torment, and honoring the connection between man and the ocean. Performances during the procession include different types of dancing.

Sericulture and silk craftsmanship of ChinaDescription: Sericulture and silk craftsmanship of China, based in Zhejiang and Jiangsu Provinces near Shanghai and Chengdu in Sichuan Province, have an ancient history. Traditionally an important role for women in the economy of rural regions, silk-making encompasses planting mulberry, raising silkworms, unreeling silk, making thread, and designing and weaving fabric. It has been handed down within families and through apprenticeship, with techniques often spreading within local groups. The life cycle of the silkworm was seen as representing the life, death and rebirth of human beings. In the ponds that dot the villages, silkworm waste is fed to fishes, while mud from the ponds fertilizes the mulberry trees, and the leaves in turn feed the silkworms. Near the beginning of the lunar year, silkworm farmers invite artisans into their homes to perform the story of the Goddess of the Silkworm, to ward off evil and ensure a bountiful harvest. Every April, female silkworm farmers adorn themselves with colourful flowers made of silk or paper and make harvest offerings as part of the Silkworm Flower festival. Silk touches the lives of rural Chinese in more material ways, too, in the form of the silk clothes, quilts, umbrellas, fans and flowers that punctuate everyday life.

|