Maxine Payne: Photographer

A Theological Interpretation of her work by Jay McDaniel

www.maxinepayne.com

Strength of Beauty. Maxine Payne takes photographs of people who work hard, who use their hands, and who live in rural settings. She likes concreteness. She likes particular people in particular circumstance who bring with them particular histories and are situated in particular places. Her aim is not to create "art" but to bear witness to the strength of beauty in their lives.

The phrase "strength of beauty" comes from the philosopher Whitehead. There's nothing abstract about it. "Strength of beauty" names the grit in a person, the gumption, the perseverance, the soulfulness. It is the intensity of a person's experience as enlivened by relations with others and also by more private yearnings, hopes, memories, and courage. You can see this strength in people's eyes, but also in their hands, their posture. And you can see it in the way people stand together, sharing strength with one another.

There is something magnetic about strength of beauty. It is not always pretty; and it may even be broken in some ways. Strength of beauty within a person's soul includes fragility. But strength of beauty has a power that attracts the mind and heart. And the eyes of Maxine Payne

The phrase "strength of beauty" comes from the philosopher Whitehead. There's nothing abstract about it. "Strength of beauty" names the grit in a person, the gumption, the perseverance, the soulfulness. It is the intensity of a person's experience as enlivened by relations with others and also by more private yearnings, hopes, memories, and courage. You can see this strength in people's eyes, but also in their hands, their posture. And you can see it in the way people stand together, sharing strength with one another.

There is something magnetic about strength of beauty. It is not always pretty; and it may even be broken in some ways. Strength of beauty within a person's soul includes fragility. But strength of beauty has a power that attracts the mind and heart. And the eyes of Maxine Payne

Co-Creativity. How does beauty -- soulfulness -- emerge? Whitehead suggests that it is partly our own creation and partly the creation of our life circumstances: the people we have known, the places we have lived, the struggles we have endured, the failures and triumphs of our lives, so often mixed together. It is illusion to think that we create ourselves independently of people and places and histories. Whiteheadians believe in relational subjectivity, not skin encapsulated subjectivity; and being "related" means being influenced, for good and ill, by others. But it is also an illusion to think that we are solely the product of those people and places and histories. We are co-created by our own agency in response to others, and the agency of others. The woman in this photograph may be by herself, but her very self -- her very process of becoming who she is becoming -- is indebted to the people she knows, the yard in which she feels comfortable, the tire and punching bag, the chair. She would not be who she is in the moment without them. They create her, too. This is what is meant by co-creativity.

People influenced by Whitehead's philosophy -- and I am among them -- propose that we are partly created by God, too. Or, more accurately, by the yearning of God as it dwells within our hearts. This divine creativity has nothing to do with an imagined act many years ago when, so the stories go, the universe came into existence. It has to do with here-and-now. Within each of us there is a desire to become whole, given who we are and given our own past histories. We do not create this desire; we discover it as we live our lives.

This desire is God's prayer within us, inwardly felt as our own prayer, too. Remember the prayer of Jesus, who taught people to pray that the will of God be done "on earth as it is in heaven." From a process or Whiteheadian perspective, the will of God "on earth" is God's prayer within each of us, namely that we find our way into whatever strength of beauty is possible for us, given the circumstances of our lives and the particularity of our situation. God is omni-adaptive and thus in process along with us, adapting to each new situation in our lives. This means that the future is open, even for God. If we are lonely, our prayer is for companionship; if we are abused by others, it is for independence. Always we are praying to become strong and beautiful. Not beautiful like the models in magazines. Not beautiful according to conventional standards. But beautiful in how we live our lives as we interact with others and are related to ourselves. Maxine Payne photographs real beauty.

People influenced by Whitehead's philosophy -- and I am among them -- propose that we are partly created by God, too. Or, more accurately, by the yearning of God as it dwells within our hearts. This divine creativity has nothing to do with an imagined act many years ago when, so the stories go, the universe came into existence. It has to do with here-and-now. Within each of us there is a desire to become whole, given who we are and given our own past histories. We do not create this desire; we discover it as we live our lives.

This desire is God's prayer within us, inwardly felt as our own prayer, too. Remember the prayer of Jesus, who taught people to pray that the will of God be done "on earth as it is in heaven." From a process or Whiteheadian perspective, the will of God "on earth" is God's prayer within each of us, namely that we find our way into whatever strength of beauty is possible for us, given the circumstances of our lives and the particularity of our situation. God is omni-adaptive and thus in process along with us, adapting to each new situation in our lives. This means that the future is open, even for God. If we are lonely, our prayer is for companionship; if we are abused by others, it is for independence. Always we are praying to become strong and beautiful. Not beautiful like the models in magazines. Not beautiful according to conventional standards. But beautiful in how we live our lives as we interact with others and are related to ourselves. Maxine Payne photographs real beauty.

Creative Ambiguity. In some of Maxine Payne's photographs we see people whom others might think a little close-minded and hard-hearted, who would be the first to help other people if they saw them stranded on the road. If we are inclined to think that the world can be divided into two kinds of people -- good people and bad people --her photography dismantles such deceptions. Indeed, it dismantles the idea that people can be framed in any way. Yes, the people we see in her photographs are en-framed by the edges of photographs, but they cannot be contained within the frames. There is an excess in them: something that jumps out of the photographs and over the frames. For the moment let's call it Creative Ambiguity.

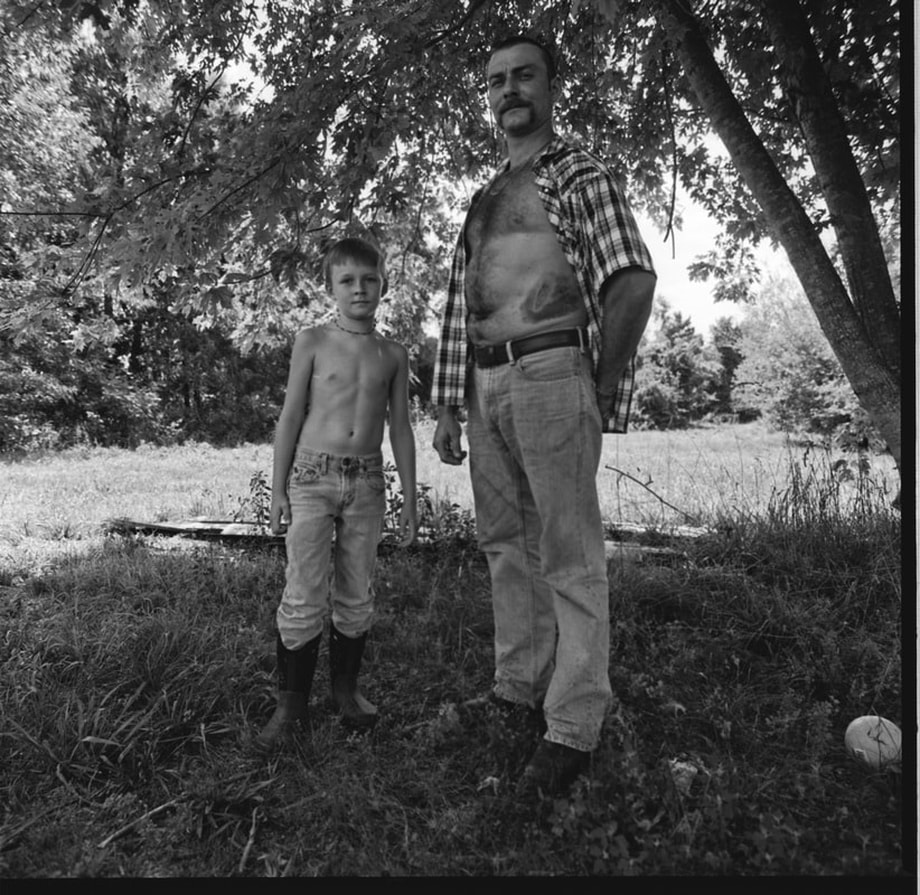

Creative Ambiguity is a verb. On the one hand it is a name for the multiple and often complicated relationships in a person's life. Look at the man in the photo. Who he is in this moment is how he is related to his family, his friends, his own past, his own future, the land, and his own innermost desire to become a whole person. In their complicatedness, these relationships are sometimes harmonized and sometimes conflicted. In addition to these relationships, there is the reality of how he manages them. Always he is negotiating the relationships and, in so doing, improvising a life out of them, day by day and moment by moment. The act of negotiating is ambiguous, too. He tries this way of being related and then that way of being related. His creativity cannot be contained in a formula.

Some of these relationships are painful. Rilke says that the key to life is not to celebrate pain, but somehow to take the grapes of bitterness and, in time, make wine of them. If you look into the eyes of the man in the photograph, or into the eyes of the boy, or into the eyes of any of the people who Maxine Payne photographs, you see wine making. Creative transformation. The people may seem to be standing in place, but in their minds and hearts they are moving. They never stay still. Strength of Beauty is a verb.

Creative Ambiguity is a verb. On the one hand it is a name for the multiple and often complicated relationships in a person's life. Look at the man in the photo. Who he is in this moment is how he is related to his family, his friends, his own past, his own future, the land, and his own innermost desire to become a whole person. In their complicatedness, these relationships are sometimes harmonized and sometimes conflicted. In addition to these relationships, there is the reality of how he manages them. Always he is negotiating the relationships and, in so doing, improvising a life out of them, day by day and moment by moment. The act of negotiating is ambiguous, too. He tries this way of being related and then that way of being related. His creativity cannot be contained in a formula.

Some of these relationships are painful. Rilke says that the key to life is not to celebrate pain, but somehow to take the grapes of bitterness and, in time, make wine of them. If you look into the eyes of the man in the photograph, or into the eyes of the boy, or into the eyes of any of the people who Maxine Payne photographs, you see wine making. Creative transformation. The people may seem to be standing in place, but in their minds and hearts they are moving. They never stay still. Strength of Beauty is a verb.

On the Way. Let's say that we really do contain within our lives something like divine Breathing or the divine Spirit, and that it takes the form of an indwelling lure toward wholeness or strength of beauty. This spirit is not all-powerful. There are many griefs from which people suffer, that were not willed or prevented by the Spirit. But process theologians believe that the spirit is all-faithful. God never gives up on anybody, and God meets each person where he is. We are beckoned by God's breathing to grow into strength of beauty, relative to our circumstances in life.

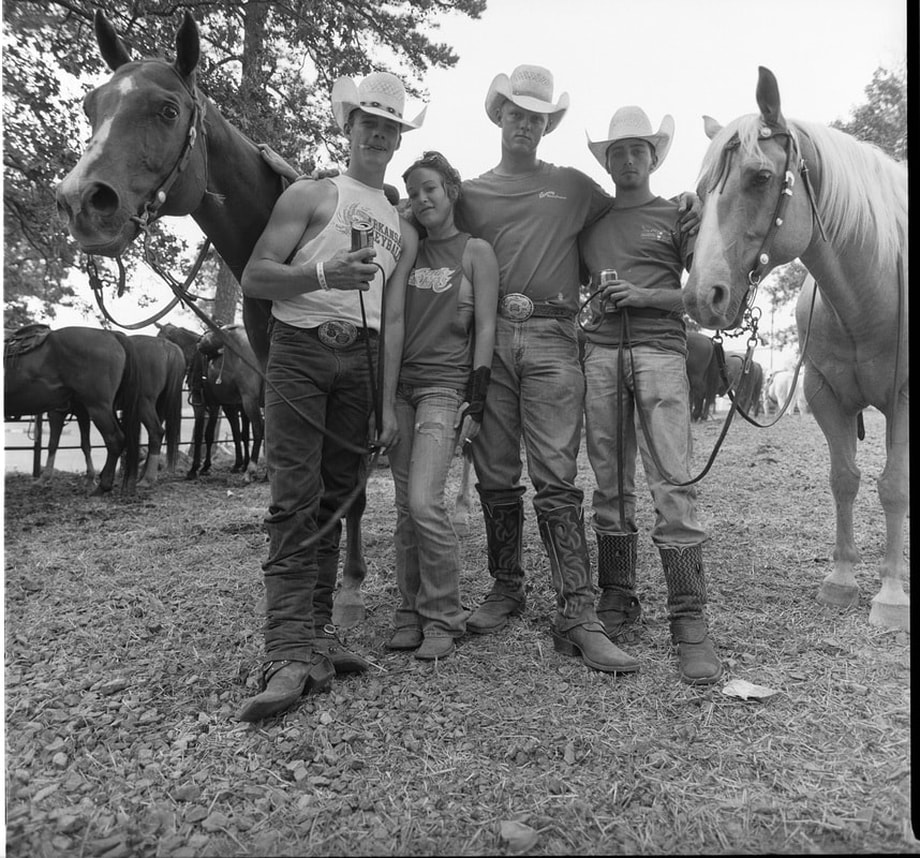

When you are young, you are often trying to figure out where you stand in the world and how you can "make your mark." Each setting presents a mark that can be made, a set of standards by which you measure yourself. Sometimes those standards are healthy, sometimes unhealthy, often both. There's no need to parcel out the difference. But there's a splendor in the very reality of youth: its boldness, its hopes, its contrivances, its insecurities, its capacity to give itself to something adventurous. There is also a need to rebel. To take the established patterns inherited from an older generation and try something new.

This need to rebel is no less holy than the need to create order. There can be no movement into beauty without a loosening of ties with the past and sometimes a rejection of the past. To be sure, later on in life, the joys of youth will become memories in an older soul. But there's no need to equate chronological age with spiritual age. Young people can have wise souls and in this sense old souls. And they can have young souls, too. Who needs to judge? At each moment a soul is itself and in this sense ageless, even as it is on its way toward something else. The timelessness lies in the immediacy of the moment at hand. There's something in the moment which touches eternity, even as it is perishing. It becomes part of the memory of God and doesn't fade. All yesterdays are today in God's evolving life.

When you are young, you are often trying to figure out where you stand in the world and how you can "make your mark." Each setting presents a mark that can be made, a set of standards by which you measure yourself. Sometimes those standards are healthy, sometimes unhealthy, often both. There's no need to parcel out the difference. But there's a splendor in the very reality of youth: its boldness, its hopes, its contrivances, its insecurities, its capacity to give itself to something adventurous. There is also a need to rebel. To take the established patterns inherited from an older generation and try something new.

This need to rebel is no less holy than the need to create order. There can be no movement into beauty without a loosening of ties with the past and sometimes a rejection of the past. To be sure, later on in life, the joys of youth will become memories in an older soul. But there's no need to equate chronological age with spiritual age. Young people can have wise souls and in this sense old souls. And they can have young souls, too. Who needs to judge? At each moment a soul is itself and in this sense ageless, even as it is on its way toward something else. The timelessness lies in the immediacy of the moment at hand. There's something in the moment which touches eternity, even as it is perishing. It becomes part of the memory of God and doesn't fade. All yesterdays are today in God's evolving life.

Knowledge: The people in Maxine Payne's photography often have a kind of knowledge urbanites lack. They know how to prime the pump when the water freezes and the pipes burst in the middle of the night. They can pull a motor of out the car or a a calf from a cow. If the world fell apart tomorrow, they would survive. Sometimes their worlds have fallen apart, and nevertheless they survive. They have strength of beauty.

This kind of knowledge or know-how is saving in its own right: namely a salvation from western modernity. Western modernity has a bias for book knowledge over practical wisdom, for elite forms of literacy at the expense of life literacy, for sophistication over rurality. There is something immensely shallow about this bias, because it neglects tradition in the name of what is new. Postmodernity, as understood by process theologians, appreciates and sometimes combines the wisdom of tradition with an appreciation of newness, the wisdom of rural living with the wisdom of urban living.

Rural people are often postmodern. They contain within their lives the myriad kinds of wisdom that are sorely needed if the world is to become more sustainable. Here sustainability does not mean endurance alone; it also means sustenance. Sustenance is the flourishing of life with life. We see it in homemaking, housebuilding, gardening, farming, beekeeping...all the activities that combine mind and body.

Of course, minds are not limited to human minds. Bees have minds, too. In their own ways they, too, embody strength of beauty. They know things and we humans know things. This beekeeper's knowledge includes the capacities to know how bees think. There are three kinds of knowledge: knowing about bees, knowing how to interact with them, and knowing with them. The beekeeper has all three.

This kind of knowledge or know-how is saving in its own right: namely a salvation from western modernity. Western modernity has a bias for book knowledge over practical wisdom, for elite forms of literacy at the expense of life literacy, for sophistication over rurality. There is something immensely shallow about this bias, because it neglects tradition in the name of what is new. Postmodernity, as understood by process theologians, appreciates and sometimes combines the wisdom of tradition with an appreciation of newness, the wisdom of rural living with the wisdom of urban living.

Rural people are often postmodern. They contain within their lives the myriad kinds of wisdom that are sorely needed if the world is to become more sustainable. Here sustainability does not mean endurance alone; it also means sustenance. Sustenance is the flourishing of life with life. We see it in homemaking, housebuilding, gardening, farming, beekeeping...all the activities that combine mind and body.

Of course, minds are not limited to human minds. Bees have minds, too. In their own ways they, too, embody strength of beauty. They know things and we humans know things. This beekeeper's knowledge includes the capacities to know how bees think. There are three kinds of knowledge: knowing about bees, knowing how to interact with them, and knowing with them. The beekeeper has all three.

MReligion. Back to prayer. Imagine that God is within each person -- and each bee, for that matter -- as a lure toward wholeness. This is God's immanence. But for process theologians God is transcendent, too. This transcendence is not that of a divine Caesar who sits on a throne, issuing commands and threatening punishment. It is that of a loving presence who cares for each living being in his or her particularity.

This caring takes the form of the Deep Memory mentioned above: of receiving all that happens in the world, moment by moment, and weaving it into whatever tapestry of beauty is possible. For process thinkers God is a person but also a journey. A person who is a journey. This journey -- God's feeling -- is an ongoing activity of feeling what we feel, moment by moment, and bearing witness to our joys and sorrows, our failures and achievements, our strength of beauty.

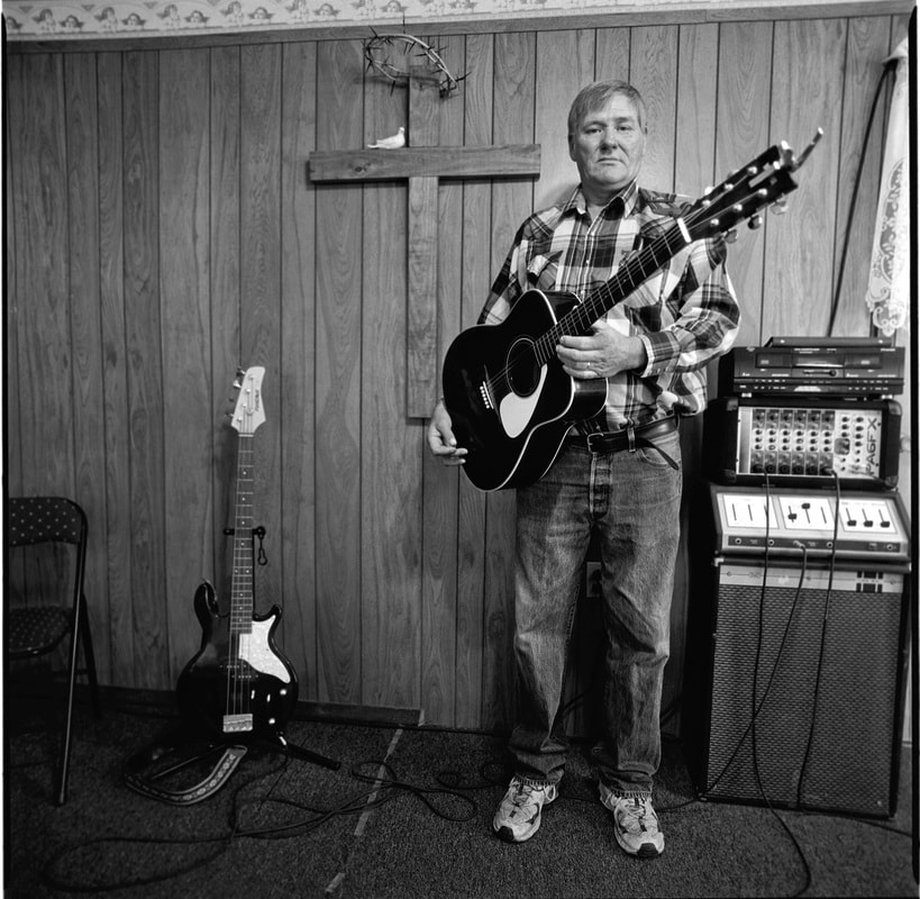

People like the man in this photograph recognize the magnificence of God's feeling. Magnificent enough to remember everything, to care for everything, to die on a cross for everything. The memory of God is the reservoir of all that is beautiful in life, and maybe all that is ugly, too. When we think of this memory, we just can't help but create a little beauty as well. With our fingers on the strings of a guitar, with our voice singing country style, with our amplifier tuned just right.

Another way to create beauty is to bear witness to it. To document it. This documentation is a form of singing, too. A prayer that each life be known, be remembered, in its creative ambiguity, its strength of beauty, its strong but fragile glory, each moment of which touches something eternal. That's what we see in the photography of Maxine Payne. She is a theologian disguised as a photographer, whose photography offers us an opportunity to pray with our eyes.

This caring takes the form of the Deep Memory mentioned above: of receiving all that happens in the world, moment by moment, and weaving it into whatever tapestry of beauty is possible. For process thinkers God is a person but also a journey. A person who is a journey. This journey -- God's feeling -- is an ongoing activity of feeling what we feel, moment by moment, and bearing witness to our joys and sorrows, our failures and achievements, our strength of beauty.

People like the man in this photograph recognize the magnificence of God's feeling. Magnificent enough to remember everything, to care for everything, to die on a cross for everything. The memory of God is the reservoir of all that is beautiful in life, and maybe all that is ugly, too. When we think of this memory, we just can't help but create a little beauty as well. With our fingers on the strings of a guitar, with our voice singing country style, with our amplifier tuned just right.

Another way to create beauty is to bear witness to it. To document it. This documentation is a form of singing, too. A prayer that each life be known, be remembered, in its creative ambiguity, its strength of beauty, its strong but fragile glory, each moment of which touches something eternal. That's what we see in the photography of Maxine Payne. She is a theologian disguised as a photographer, whose photography offers us an opportunity to pray with our eyes.

Maxine Payne is a photographer living and working in Arkansas, where her grandparents raised her. She received her M.F.A from the University of Iowa where she was also an Iowa Arts Fellow. Maxine was selected a Fellow of the American Photography Institute at New York University, as well as a Fellow of the College Art Association. She works to find ways to engage community in her work and speaks to the idea of place. Her work has been shown nationally. Currently, Maxine is the Judy and Randy Wilbourn Odyssey Professor, an Associate Professor of Art and Chair of the Art Department at Hendrix College in Conway, Arkansas. She has collaborated with anthropologist Anne Goldberg documenting the lives of rural women in Costa Rica, the U.S./Mexico border and Africa. She is also collaborating with biologist Matthew Moran to document the environment and people of the “Big Woods” region in Arkansas. She has photographed hundreds of Arkansas Historic Bridges for the Arkansas Highway and Transportation Department since 2004. Her work can be seen at www.MaxinePayne.com.