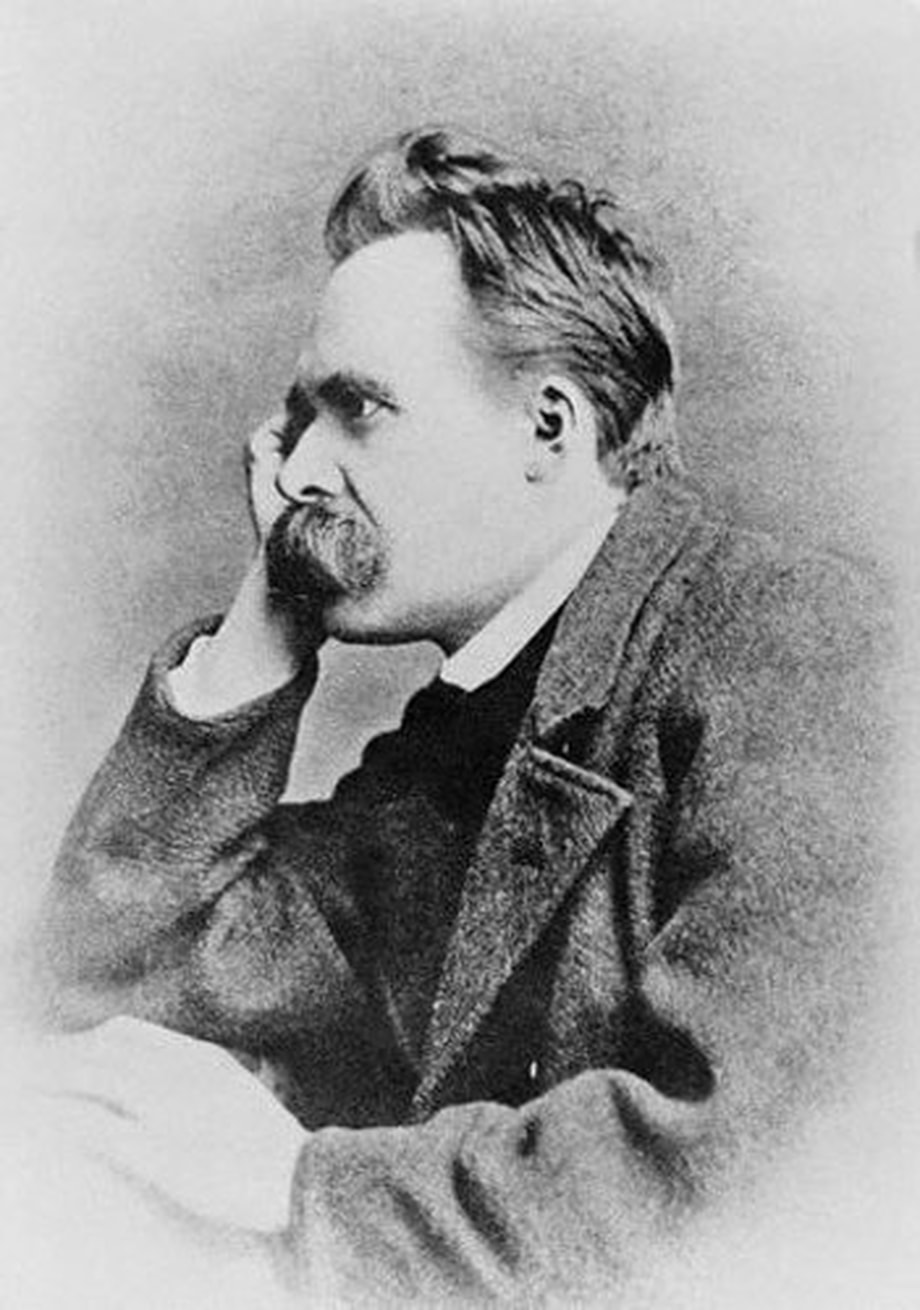

Nietzsche's Genealogy of Morality

An Invitation to Honesty

Those of us in the open and relational (process) tradition are not known for our love of Friedrich Nietzsche. He preached the death of God and we preach the life of God, But the very God in whom we believe is an inwardly felt lure to be honest about the world and ourselves. God is an invitation to honesty, and so is Nietzsche. We cannot help but wonder if the God in whom we believe meets us, among other ways, in a man who proclaimed God's death.

Hence the need to take seriously Nietzsche's "On the Genealogy of Morality." It consists of three essays that delve into the origins and development of moral concepts. Nietzsche contrasts two types of moralities: slave morality and master morality. Slave morality originates from the weak and oppressed, valuing traits such as humility, meekness, and compassion. In contrast, master morality arises from the powerful and dominant, emphasizing qualities like strength, power, and assertiveness.

Nietzsche argues that the slave, driven by resentment and a desire for revenge, engages in a "transvaluation of values." The slave seeks to invert the values of the master, deeming master virtues as vices and slave vices as virtues. This transvaluation is an attempt by the weak to assert their own moral superiority and to undermine the dominance of the strong. Nietzsche argues that resentful morality restricts human potential and hinders the development of higher, more life-affirming values. Nietzsche associates Christianity with slave morality. In his view, it is anti-vitality, anti-life.

Nietzsche's views can help us understand the current political situation in the United States and other nations, particularly the rise of authoritarianism.

Often authoritarian rulers embody the values Nietzsche associates with master morality: strength, power, honor, and assertiveness. These rulers are not meek, humble, or compassionate, and wouldn't want to be. They are easily offended; they fight back; and the very expression of forgiveness would be, for them, a "weakness." Here, however, three ironies emerge:

The first is that the authoritarian rulers and their supporters are filled with a kind of resentment characteristic of what he calls slave morality. They are resentful of those who, in their view, falsely usurp power they desire, otherwise called "liberals."

The second is that the liberals they often speak for the values of what Nietzsche calls slave morality, especially compassion. The liberals want a compassionate society in which everyone is included and no one is left behind, and in which the dignity of each person is respected. The liberal ideal is what Nietzsche would call Christian.

The third irony is that the authoritarian rulers and their supporters speak of themselves as Christian even as they highlight the values of master morality: strength over weakness, domination over compassion. Thus they transvaluate the values of Christianity, redefining it in terms of master morality.

Amid these ironies, many of Nietzsche's proposals are well worth considering. They are:

We in the process tradition believe these claims should be faced honestly and openly, not defensively. Nietzsche to the contrary, we believe God who inspires us to seek truth is also a lure toward satisfaction and vitality, toward what we call "richness of experience." And again Nietzsche to the contrary, we believe that humility, forgiveness, and compassion are expressions of, not exceptions to, such vitality. These derive from the very love ethic Nietzsche rejected. Ours is what he would call a slave morality.

But we welcome Nietzsche's critique, including his recognition that much religion is profoundly unhealthy, including our own, And we welcome his warning that our own high ideals may emerge from mixed motives, including resentment, jealousy, and a desire for revenge. Nietzsche challenges us, not only to examine the world around us, but also to examine ourselves.

In "On the Genealogy of Morality" Nietzsche points out that the very tradition of self-examination is a Christian virtue, not characteristic of the master class. The powerful are not introspective. They do not spend time looking in the mirror and asking "What are my values?" They are not interested in exploring hidden motivations of the inner life. They simply act out of their will-to-power.

Process theology diverges from the master class. It sees the self-examination and an exploring of interiority as a form of rich experience in its own right and a precondition for self-transcending selfhood. We cannot transcend ourselves unless we know ourselves. Nietzsche's "On the Genealogy of Mortality" is an invitation to honesty.

- Jay McDaniel

Hence the need to take seriously Nietzsche's "On the Genealogy of Morality." It consists of three essays that delve into the origins and development of moral concepts. Nietzsche contrasts two types of moralities: slave morality and master morality. Slave morality originates from the weak and oppressed, valuing traits such as humility, meekness, and compassion. In contrast, master morality arises from the powerful and dominant, emphasizing qualities like strength, power, and assertiveness.

Nietzsche argues that the slave, driven by resentment and a desire for revenge, engages in a "transvaluation of values." The slave seeks to invert the values of the master, deeming master virtues as vices and slave vices as virtues. This transvaluation is an attempt by the weak to assert their own moral superiority and to undermine the dominance of the strong. Nietzsche argues that resentful morality restricts human potential and hinders the development of higher, more life-affirming values. Nietzsche associates Christianity with slave morality. In his view, it is anti-vitality, anti-life.

Nietzsche's views can help us understand the current political situation in the United States and other nations, particularly the rise of authoritarianism.

Often authoritarian rulers embody the values Nietzsche associates with master morality: strength, power, honor, and assertiveness. These rulers are not meek, humble, or compassionate, and wouldn't want to be. They are easily offended; they fight back; and the very expression of forgiveness would be, for them, a "weakness." Here, however, three ironies emerge:

The first is that the authoritarian rulers and their supporters are filled with a kind of resentment characteristic of what he calls slave morality. They are resentful of those who, in their view, falsely usurp power they desire, otherwise called "liberals."

The second is that the liberals they often speak for the values of what Nietzsche calls slave morality, especially compassion. The liberals want a compassionate society in which everyone is included and no one is left behind, and in which the dignity of each person is respected. The liberal ideal is what Nietzsche would call Christian.

The third irony is that the authoritarian rulers and their supporters speak of themselves as Christian even as they highlight the values of master morality: strength over weakness, domination over compassion. Thus they transvaluate the values of Christianity, redefining it in terms of master morality.

Amid these ironies, many of Nietzsche's proposals are well worth considering. They are:

- that much human life is in fact motivated by a will-to-power: a desire for recognition and respect.

- that much "morality" is grounded in jealousy and resentment: a jealousy of others in power.

- that the politics of resentment feeds upon something deep within the human psyche, not easily eradicated by appeals to higher values.

- that many Christians, in their appeals to humility, are motivated by resentment but not love.

- that Christianity itself has no fixed essence but evolves continuously, relative to circumstances and power-relations

We in the process tradition believe these claims should be faced honestly and openly, not defensively. Nietzsche to the contrary, we believe God who inspires us to seek truth is also a lure toward satisfaction and vitality, toward what we call "richness of experience." And again Nietzsche to the contrary, we believe that humility, forgiveness, and compassion are expressions of, not exceptions to, such vitality. These derive from the very love ethic Nietzsche rejected. Ours is what he would call a slave morality.

But we welcome Nietzsche's critique, including his recognition that much religion is profoundly unhealthy, including our own, And we welcome his warning that our own high ideals may emerge from mixed motives, including resentment, jealousy, and a desire for revenge. Nietzsche challenges us, not only to examine the world around us, but also to examine ourselves.

In "On the Genealogy of Morality" Nietzsche points out that the very tradition of self-examination is a Christian virtue, not characteristic of the master class. The powerful are not introspective. They do not spend time looking in the mirror and asking "What are my values?" They are not interested in exploring hidden motivations of the inner life. They simply act out of their will-to-power.

Process theology diverges from the master class. It sees the self-examination and an exploring of interiority as a form of rich experience in its own right and a precondition for self-transcending selfhood. We cannot transcend ourselves unless we know ourselves. Nietzsche's "On the Genealogy of Mortality" is an invitation to honesty.

- Jay McDaniel