- Home

- Process Worldview

- Community

- Art and Music

- Whitehead and Process Thinking

- Podcasts

- Spirituality

- Ecological Civilization

- Education

- Contact

- Social Justice

- Science

- Animals

- Sacred Poems

- Whitehead Videos

- Index of All Titles

- Practicing Process Thought

- Process Spirituality: A Spiritual Alphabet

- Recent Posts

Iris Murdoch

A Scholarly Discussion

BBC In Our Time

Whitehead and Murdoch

reflections after listening to the podcast

A decade or so ago, while giving lectures in mainland China on Whitehead's philosophy, I discovered Iris Murdoch. My Chinese translator was working on her PhD in English literature at a Chinese university, and her specialty was Iris Murdoch, novelist and philosopher. I asked her what appealed to her about Murdoch's philosophy, and she said something to the effect:

"She invites us to live from the light of the Good, even if we don't believe in a personal God. For her God becomes the Good."

I was curious. I thought of Plato, who thinks of the Good as a transcendent reality discoverable through intellectual ascent, much as a cave dweller might ascend a cave to the light of the sun; and also of Whitehead, who thinks that ideals such as Goodness and Truth and Beauty are part of the very fabric of the universe, discoverable in human experience in many ways. For Whitehead as for Plato, we live in a universe that includes ideals that are independent of our projection. Murdoch was quite influenced by Plato, and her thought resembles the Platonic side of Whitehead.

Whitehead's aim was to offer a "philosophy of organism" that would build upon and help integrate, insights from science, art, morality, and religion. With regard to science, he was especially influenced by early quantum theory and relativity theories. With regard to art, he was influenced by the poetry of Wordsworth, with its understanding of the natural world as alive with vitality and value. With regard to morality, he was influenced by ideals such as love, peace, and tenderness. And with regard to religion, he was influenced by the image of Jesus, though not himself a theologian. He wanted to pull all of these influences into a conceptual whole, a philosophical gestalt, that might help people make sense of the world and contribute to overall well-being.

Whitehead believed in an objective world of facts, of atoms and molecules, planets and stars, current events and historical circumstances. He was a realist. But he rejected the idea that facts are devoid of value. For him as for Murdoch, the fact of another person's life is also the value that another person has for herself, and this value is part of the facts of the world. It is a fact that the other person is important to herself, and this fact is as objective as, say, her genetic makeup and place in the world. The person is a fact and a value at the same time. He would say the same for other animals, for living cells, and even, given his view that wherever there is energy there is something like feeling, for quantum events in the depths of matter.

For Whitehead the entire universe is best imagined on the analogy of living beings. It consists of facts with intrinsic value, each connected to the all the others. The universe is a web of connections. Additionally, as Andrew Davis emphasizes in Mind, Body, and Cosmos, Whitehead believed in transcendent ideals such as Truth, Goodness, and Beauty. These ideals are not living beings in their own right, but they are part of reality. We don't create them, we discover them; and they make a claim upon us.

As my Chinese translator explained her attraction to Murdoch, I wondered if there might be a marriage of sorts between Whitehead and Murdoch. Perhaps Whitehead offers a cosmology to support Iris Murdoch's understanding of the moral life, and Murdoch, in her novels and in her philosophy, offers a vision of the moral life to deepen Whitehead's cosmology.

If this is the case, there are aspects of Whitehead's philosophy that will not come into play. In Process and Reality Whitehead speaks of God as a living subject, the Mind of the universe, with feelings of God's own. In other words, he speaks of a personal God. For Murdoch this is not an option. She believes in the Good but not the personal God. And for Whitehead our experience of transcendent ideals is one way of experiencing God, who is discovered through the lure of such ideals. Murdoch speaks of the Good without reference to God as a source or catalyst for such ideals.

However, it remains the case that Whitehead often speaks of God in non-personal terms: as the Eros of the universe and the Harmony of Harmonies, for example. Additionally, he speaks of the "secular" function of God, suggesting that people can refer to God without specifically religious feelings. And the image of God he offers is pan-en-theistic not theistic. God is not outside the universe in another plane; God it the mind of the universe. Finally, it is clear that Whitehead believes people can experience transcendent ideals without believing in God. All of this suggests to me that Whitehead would be sympathetic to Murdoch's perspective.

*

For Murdoch, novelist and philosopher, the moral life is not rigid or mechanical. It is a process of breaking free from what she calls "the fat, relentless ego" and the self-centered fantasies it imposes upon the world in order to live in a more humane and relational way, animated by feelings as well as ideas. The process unfolds, not by following an algorithm for good deeds or a book of rules, but by paying attention to something or someone other than yourself and being unselfed, or freed from egocentrism. in the act of attention. As we are unselfed in this way, we gain a glimpse of what Plato would call The Good. The Good that we glimpse is not a personal God with feelings and aims. But it is not a mere projection of the mind onto the world. It is an objective and transcendent reality, as real in its way as are the facts of the world. The moral life lies in making gradual progress so what we can be guided, not by whims and fantasies, not by selfishness, but rather by the Light of the Good.

These ideas are contradicted by the dominant picture of the world that many carry today, and that is communicated twenty-four hours a day on radio, television, and the internet. Whitehead calls it scientific materialism. The world is pictured as a collection of facts devoid of value until the latter (the values) are imposed upon the world by human beings.

Murdoch, by contrast, sees the world in a more Whiteheadian way. She sees it as a world of subjects who have value in their own right. She writes; "Man is a creature who makes pictures of himself and comes to resemble the picture. We tell ourselves stories and end up imitating them. That's a way in which we navigate the world." Murdoch found herself in a world dominated by the picture of the natural world devoid of meaning and stripped of morality.

"Murdoch wants us to reject that way of thinking about the world, not because she thinks there's a God somewhere who puts meaning on the world. She rejects the picture because she thinks the world contains other people - complicated, ordinary people of the sort you find in her novels - and once you have the people in the world you have goodness in the world. And although it's dim and difficult to see, we can work hard and try to break through our selfish egos and come to be guided by the light of goodness. That's a different picture of the world, a much more humane picture. That's the legacy she leaves philosophy, What she gives us is a very different way of thinking about the world." (Anil Gomes, In our Times podcast above)

Whitehead, it seems to me, offers a very different way of thinking about the world.

*

Whitehead's different way of thinking often comes across as overly abstract, overly concerned with 'principles' but lacking in stories from real life. While Whitehead appreciates the role of imagination in human life, his philosophy lacks the imaginative content that is offered by Murdoch's novels. Here is a description of a few of them from chatGPT.

- "Under the Net" (1954): This is Murdoch's debut novel and is considered a classic of post-war English literature. The book follows the misadventures of a struggling writer named Jake Donaghue, who navigates his way through London's literary circles in the 1950s.

- "The Black Prince" (1973): This novel explores themes of love and morality, and is widely regarded as one of Murdoch's most complex and challenging works. The story follows the relationship between a young writer and a wealthy, middle-aged widow, and raises questions about the nature of love, power, and identity.

- "The Sea, The Sea" (1978): This novel won the Booker Prize in 1978 and is widely regarded as one of Murdoch's most accessible and engaging works. The story follows a retired theatre director named Charles Arrowby, who retreats to a remote coastal town and becomes obsessed with his past loves.

- "The Bell" (1958): This novel explores themes of spirituality and community, and is considered one of Murdoch's most philosophical works. The story follows a group of characters living in a small, isolated religious community in England, and raises questions about the nature of faith, morality, and human relationships.

- "A Severed Head" (1961): This novel is a darkly comic exploration of love, betrayal, and jealousy. The story follows a group of upper-class Londoners whose lives are turned upside down when a husband discovers that his wife is having an affair with his best friend.

You will find none of this in Whitehead. He was a philosopher not a novelist. By contrast, Murdoch was a philosopher and a novelist.

True, Murdoch did not think of her novels as philosophical novels, as if their purpose was to illustrate abstract ideas. She thought of them as novels per se, the purpose of which is to take readers into the world of human relationships in all their complexity, so that they - we - might be better able to live morally and humanely.

This aim on her part is itself important even to philosophy, at least of the Whiteheadian type. Whitehead's philosophy best functions, not simply as an account of the way things are or might be, but as a form of medicine or healing. Its purpose is to help bring about a better world, with transformed souls as well as transformed communities. Process philosophers today speak of four hopes that guide the process movement: whole persons, whole communities, a whole planet, and holistic thinking. Process philosophy is in service to these hopes. Toward this end it needs stories - just the kind that Murdoch and other novelists offer.

Today these stories are present in film and music, no less than novels. But the point is the same. Stories change the heart in ways that transcend philosophy. I do not know if Murdoch's moral vision needs Whitehead's cosmology in order to gain traction in the 21st century. What seems clear to me that Whitehead needs stories like Murdoch's in order to gain traction. Murdock humanizes Whitehead.

*

And what about Whitehead's notion of God as a divine companion, a fellow sufferer who understands, who operates through the tender elements in life. This is the personal God that does not seem "real" to many in the world today. Murdoch believe in the Good but not in God. Whitehead believed in God and the Good. The two ideas lie on a continuum. Perhaps even believers find themselves drawn to the Good on some days and God on others. They slide back and forth, relative to context. I think such sliding might make good sense to Whitehead. Who knows? It might even make a little sense to Murdoch.

The phrase no God but the Good can mean that there is no personal God at all, there is only the Good, which replaces God. It can also mean that there is a personal God whose very nature is Goodness and that apart from this way of understanding God, there is no God at all. Either way the question then becomes: What is the Good? Iris Murdoch believed it is love. Whitehead did as well. He envisioned the personal God, the God who feels the feelings of all in a sympathetic way, as defined by love. Iris Murdoch was inclined toward the first view. The God of traditional belief is non-existent, but the Good itself is quite real. The need today is for us to recognize the universe includes Goodness as part of its very nature, God or no God.

- Jay McDaniel

Murdoch's Unselfing and

Whitehead's World Loyalty

What is unselfing in Iris Murdoch and how does it

compare with Whitehead's idea of World Loyalty?

"Unselfing" is a term coined by the philosopher and novelist Iris Murdoch. She used it to describe a process of transcending the self, which she believed was necessary for achieving moral and spiritual growth.

Murdoch spelled the term as "unselfing," which she defined as "the movement away from self-centeredness and towards a greater concern for others." Unselfing involves a process of breaking down the ego and expanding one's sense of identity to include the broader world and other individuals.

According to Murdoch, unselfing requires a combination of moral effort and aesthetic attention. Through sustained moral effort, individuals can cultivate habits of selflessness and compassion. Through aesthetic attention, they can develop a greater sensitivity to the beauty and complexity of the world around them, which can inspire them to act in ways that are more altruistic and compassionate.

Overall, Murdoch saw unselfing as a crucial component of moral and spiritual growth, and she believed that it was necessary for creating a more just and compassionate society.

*

Iris Murdoch's concept of "unselfing" is the process of moving beyond one's own individual ego and becoming more attuned to the world around us. It involves transcending the narrow confines of our own subjective experience and opening ourselves up to the wider reality of others and the world. According to Murdoch, unselfing involves a kind of self-forgetfulness, where we are less preoccupied with our own desires and concerns and more focused on the needs and perspectives of others.

Whitehead's concept of "world loyalty" is somewhat similar to Murdoch's idea of unselfing, in that it emphasizes a deep connection to the world around us. Whitehead argues that we should be loyal to the world, rather than to our own individual selves. This means that we should prioritize the well-being of the world as a whole, rather than our own narrow self-interests.

However, there are also some differences between the two concepts. Murdoch's unselfing is primarily focused on the individual's inner transformation, while Whitehead's world loyalty is more focused on our relationship to the external world. Additionally, while Murdoch's unselfing is concerned with a kind of self-transcendence or self-forgetfulness, Whitehead's world loyalty is more concerned with a sense of responsibility towards the world and the interconnectedness of all things.

Overall, both concepts emphasize the importance of moving beyond our own narrow self-interests and becoming more attuned to the wider reality of the world around us. However, they approach this goal from slightly different angles and with different emphases.

Murdoch spelled the term as "unselfing," which she defined as "the movement away from self-centeredness and towards a greater concern for others." Unselfing involves a process of breaking down the ego and expanding one's sense of identity to include the broader world and other individuals.

According to Murdoch, unselfing requires a combination of moral effort and aesthetic attention. Through sustained moral effort, individuals can cultivate habits of selflessness and compassion. Through aesthetic attention, they can develop a greater sensitivity to the beauty and complexity of the world around them, which can inspire them to act in ways that are more altruistic and compassionate.

Overall, Murdoch saw unselfing as a crucial component of moral and spiritual growth, and she believed that it was necessary for creating a more just and compassionate society.

*

Iris Murdoch's concept of "unselfing" is the process of moving beyond one's own individual ego and becoming more attuned to the world around us. It involves transcending the narrow confines of our own subjective experience and opening ourselves up to the wider reality of others and the world. According to Murdoch, unselfing involves a kind of self-forgetfulness, where we are less preoccupied with our own desires and concerns and more focused on the needs and perspectives of others.

Whitehead's concept of "world loyalty" is somewhat similar to Murdoch's idea of unselfing, in that it emphasizes a deep connection to the world around us. Whitehead argues that we should be loyal to the world, rather than to our own individual selves. This means that we should prioritize the well-being of the world as a whole, rather than our own narrow self-interests.

However, there are also some differences between the two concepts. Murdoch's unselfing is primarily focused on the individual's inner transformation, while Whitehead's world loyalty is more focused on our relationship to the external world. Additionally, while Murdoch's unselfing is concerned with a kind of self-transcendence or self-forgetfulness, Whitehead's world loyalty is more concerned with a sense of responsibility towards the world and the interconnectedness of all things.

Overall, both concepts emphasize the importance of moving beyond our own narrow self-interests and becoming more attuned to the wider reality of the world around us. However, they approach this goal from slightly different angles and with different emphases.

Has there been any scholarly discussion comparing the ideas of Alfred North Whitehead and Iris Murdoch?

Yes, there has been some scholarly discussion comparing the ideas of Alfred North Whitehead and Iris Murdoch, particularly in the areas of philosophy, ethics, and metaphysics.

Both Whitehead and Murdoch were British philosophers who made significant contributions to various areas of philosophy. Whitehead was known for his work in process philosophy and metaphysics, while Murdoch was known for her work in moral philosophy and literature.

One area where their ideas intersected was in their understanding of the relationship between the individual and the larger world or universe. Whitehead's process philosophy emphasized the interconnectedness of all things, and how individuals are not isolated entities but rather are part of a larger whole. Similarly, Murdoch's moral philosophy emphasized the importance of recognizing the interconnectedness of all beings and how ethical behavior involves acknowledging and responding to the needs of others.

Another area where their ideas overlapped was in their understanding of the nature of reality. Whitehead's process philosophy posited that reality is constantly changing and evolving, while Murdoch's philosophical approach emphasized the importance of being attentive to the particularities of individual experience and how they shape our understanding of reality. For Whitehead "experience" was a fundamental concept. He believed that all actualities are acts of "experiencing" other realities consciously or unconsciously.

Some scholars have also noted similarities between Murdoch's emphasis on the importance of imagination and Whitehead's concept of "prehension," which refers to the way in which entities are "taken up" or experienced by other entities. Whereas Whitehead offers a cosmological account of experience, Murdoch's novels offer more concrete, narrative presentations of experience.

- chatGPT with help from Jay McDaniel

Both Whitehead and Murdoch were British philosophers who made significant contributions to various areas of philosophy. Whitehead was known for his work in process philosophy and metaphysics, while Murdoch was known for her work in moral philosophy and literature.

One area where their ideas intersected was in their understanding of the relationship between the individual and the larger world or universe. Whitehead's process philosophy emphasized the interconnectedness of all things, and how individuals are not isolated entities but rather are part of a larger whole. Similarly, Murdoch's moral philosophy emphasized the importance of recognizing the interconnectedness of all beings and how ethical behavior involves acknowledging and responding to the needs of others.

Another area where their ideas overlapped was in their understanding of the nature of reality. Whitehead's process philosophy posited that reality is constantly changing and evolving, while Murdoch's philosophical approach emphasized the importance of being attentive to the particularities of individual experience and how they shape our understanding of reality. For Whitehead "experience" was a fundamental concept. He believed that all actualities are acts of "experiencing" other realities consciously or unconsciously.

Some scholars have also noted similarities between Murdoch's emphasis on the importance of imagination and Whitehead's concept of "prehension," which refers to the way in which entities are "taken up" or experienced by other entities. Whereas Whitehead offers a cosmological account of experience, Murdoch's novels offer more concrete, narrative presentations of experience.

- chatGPT with help from Jay McDaniel

Please give me a bibliography of articles comparing the work of Iris Murdoch and Alfred North Whitehead.

Here are a few articles that compare the ideas of Iris Murdoch and Alfred North Whitehead:

These articles should provide a good starting point for anyone interested in exploring the similarities and differences between the ideas of Iris Murdoch and Alfred North Whitehead.

- chatGPT

- Brennan, Tad. "Iris Murdoch and Alfred North Whitehead: The World as One Self-Organizing Whole." Philosophy Today 54, no. 1 (2010): 69-81.

- Cristi, Marcela. "The Ethics of Attention: Iris Murdoch and Alfred North Whitehead." Process Studies 44, no. 1 (2015): 41-60.

- Dobbins, Michael J. "Iris Murdoch and Alfred North Whitehead: A Comparative Study." Journal of the British Society for Phenomenology 33, no. 2 (2002): 147-160.

- Llewelyn, John. "Murdoch and Whitehead: On Imagination." In The Aesthetics of Iris Murdoch, edited by Anne Rowe and Avril Horner, 85-98. London: Legenda, 2010.

- Stenning, Peter. "The Ethical Significance of Whitehead's Ontology for the Thought of Iris Murdoch." European Journal of Philosophy 18, no. 4 (2010): 521-539.

- Tiberghien, Dominique. "Whitehead and Murdoch on Imagination." In Alfred North Whitehead: The Man and His Work, vol. 2, edited by Victor Lowe and David R. Griffin, 104-120. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1985.

These articles should provide a good starting point for anyone interested in exploring the similarities and differences between the ideas of Iris Murdoch and Alfred North Whitehead.

- chatGPT

Reading List for Iris Murdoch

offered by BBC's In Our Times

John Bayley, Iris: A Memoir of Iris Murdoch (Duckworth, 1998)

Justin Broackes (ed.), Iris Murdoch, Philosopher (Oxford University Press, 2014)

Gary Browning, Why Iris Murdoch Matters (Bloomsbury, 2018)

A.S. Byatt, Degrees of Freedom: The Novels of Iris Murdoch (Vintage, 1994)

Peter J Conradi, Iris Murdoch: A Life (HarperCollins, 2001)

Peter J. Conradi, Iris Murdoch: The Saint and the Artist (HarperCollins, 2001)

Peter J. Conradi, A Writer at War: Iris Murdoch 1935-1945 (Short Books, 2010)

Gillian Dooley (ed.), From A Tiny Corner in the House of Fiction: Conversations with Iris Murdoch (University of South Carolina Press, 2003)

Mark Hopwood and Silvia Panizza (eds.), The Murdochian Mind (Routledge, forthcoming), especially ‘Iris Murdoch: Moral Vision’ by Anil Gomes

Avril Horner and Anne Rowe, Living on Paper: Letters from Iris Murdoch 1939-1995 (Chatto & Windus, 2015)

Priscilla Martin and Anne Rowe, Iris Murdoch: A Literary Life (Palgrave Macmillan, 2010)

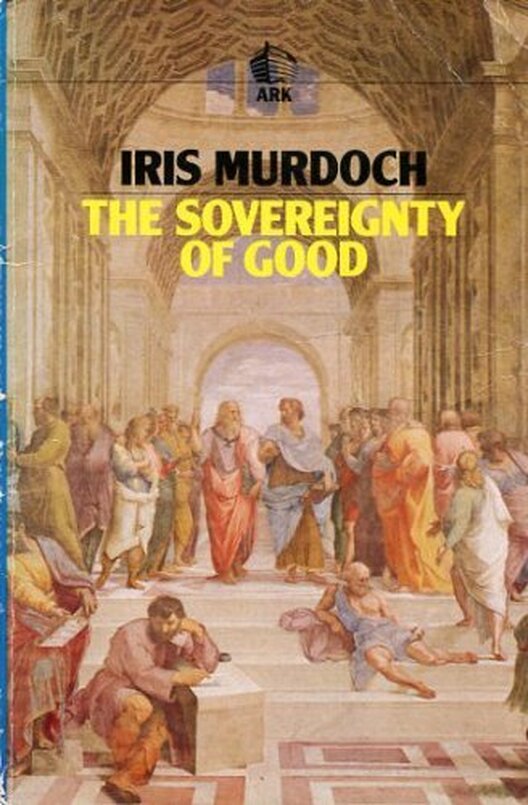

Iris Murdoch, The Sovereignty of Good (Routledge, 2001)

Iris Murdoch, Metaphysics as a Guide to Morals (Penguin, 1993)

Anne Rowe, Iris Murdoch: Writers and Their Work (Liverpool University Press, 2019)

Frances White, Becoming Iris Murdoch (Kingston University Press, 2014)

RELATED LINKS

Iris Murdoch Society

The Iris Murdoch Research Centre, University of Chichester

‘Iris Murdoch and the power of love’ by Anil Gomes

Iris Murdoch - Wikipedia

Justin Broackes (ed.), Iris Murdoch, Philosopher (Oxford University Press, 2014)

Gary Browning, Why Iris Murdoch Matters (Bloomsbury, 2018)

A.S. Byatt, Degrees of Freedom: The Novels of Iris Murdoch (Vintage, 1994)

Peter J Conradi, Iris Murdoch: A Life (HarperCollins, 2001)

Peter J. Conradi, Iris Murdoch: The Saint and the Artist (HarperCollins, 2001)

Peter J. Conradi, A Writer at War: Iris Murdoch 1935-1945 (Short Books, 2010)

Gillian Dooley (ed.), From A Tiny Corner in the House of Fiction: Conversations with Iris Murdoch (University of South Carolina Press, 2003)

Mark Hopwood and Silvia Panizza (eds.), The Murdochian Mind (Routledge, forthcoming), especially ‘Iris Murdoch: Moral Vision’ by Anil Gomes

Avril Horner and Anne Rowe, Living on Paper: Letters from Iris Murdoch 1939-1995 (Chatto & Windus, 2015)

Priscilla Martin and Anne Rowe, Iris Murdoch: A Literary Life (Palgrave Macmillan, 2010)

Iris Murdoch, The Sovereignty of Good (Routledge, 2001)

Iris Murdoch, Metaphysics as a Guide to Morals (Penguin, 1993)

Anne Rowe, Iris Murdoch: Writers and Their Work (Liverpool University Press, 2019)

Frances White, Becoming Iris Murdoch (Kingston University Press, 2014)

RELATED LINKS

Iris Murdoch Society

The Iris Murdoch Research Centre, University of Chichester

‘Iris Murdoch and the power of love’ by Anil Gomes

Iris Murdoch - Wikipedia

The Sovereignty of Good

overview

Iris Murdoch's "The Sovereignty of Good" is a collection of three essays that explore the nature of goodness, morality, and the role of art in human life. Here are some of the key ideas presented in the book:

Overall, Murdoch's book is an exploration of the nature of morality and goodness, and a call to reevaluate our traditional ways of thinking about these concepts. She challenges us to embrace the complexity and richness of ethical life, and to recognize the power and importance of our own individual choices and actions.

- chatGPT

- Goodness is not a simple or straightforward concept. Murdoch argues that goodness is not a set of rules or principles that can be easily defined or followed. Instead, it is a complex and dynamic quality that emerges from our interactions with the world and with other people. Goodness is something that we must cultivate through our choices and actions, rather than something that can be imposed upon us from outside.

- The concept of morality has been oversimplified. Murdoch argues that traditional moral theories, which focus on duty, obligation, and rules, have led us to overlook the importance of personal responsibility and individual choice. She believes that morality should be more about developing a sense of moral vision and imagination, which allows us to see the world and other people in a new way and act accordingly.

- Art has an important role to play in shaping our moral vision. Murdoch believes that art can help us to see the world more clearly and to develop a deeper understanding of ourselves and others. By experiencing art, we can become more attuned to the complexities of human experience and better equipped to make ethical choices.

- The idea of the "sovereignty of good" refers to the idea that goodness has a kind of inherent power or authority. Murdoch argues that the pursuit of goodness is not just a personal choice, but something that has a transcendent value and significance. By striving to be good, we can create a better world and contribute to a greater sense of meaning and purpose in life.

Overall, Murdoch's book is an exploration of the nature of morality and goodness, and a call to reevaluate our traditional ways of thinking about these concepts. She challenges us to embrace the complexity and richness of ethical life, and to recognize the power and importance of our own individual choices and actions.

- chatGPT