- Home

- Process Worldview

- Community

- Art and Music

- Whitehead and Process Thinking

- Podcasts

- Spirituality

- Ecological Civilization

- Education

- Contact

- Social Justice

- Science

- Animals

- Sacred Poems

- Whitehead Videos

- Index of All Titles

- Practicing Process Thought

- Process Spirituality: A Spiritual Alphabet

- Recent Posts

O Shut Up!

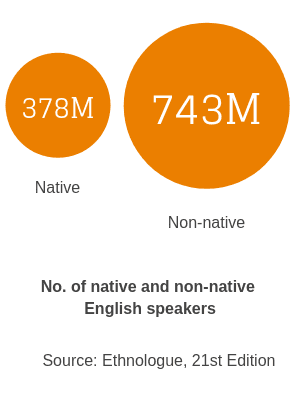

The Unpleasant Arrogance

of Native English Speakers

Englisholatry

English dominates financy, science and industry, universities, advertising, computing, publishing, entertainment, international organizations. and international transportation. This dominance is the legacy British and American imperialism, and there is no escaping it. Those of us who for whom English is our first and often only language often fall into the arrogance of thinking (1) that everyone should speak English, (2) that there is one 'real' English language, namely the one that sounds right to us, (3) that people for whom English is a second or third or fourth language should understand our jokes and idioms, (4) that the Bible was written in English, (5) that God's first language is English, and (6) that we need not study and learn other languages except as a hobby. If we fall into any of these errors, it's time to name and claim our shadow: Englisholatry. It's time to be honest about our arrogance, listen to people who speak other languages, learn other languages ourselves, and, sometimes, just shut up.

"It's hard to be heard in an English-speaking world"

It is just hard for non-English speakers to make themselves heard in an English-speaking world.

Since English is not my native tongue, I am familiar with the effort involved in writing and speaking another language — even though my native Dutch is probably the closest another language can come to English. Scientists from other places have to make ten times the effort. English itself is of course not the problem: It is not better or worse than any other language. The problem is the attitude of native English speakers.

Naturally, you speak your own language faster and better than any other. This can make it impossible for those who are not native English speakers to keep up at international meetings. It is worse on those occasions when an English speaker doesn’t pull any punches while debating with a scientist whose English is poor.

I have seen it happen often. The English speaker rises from the audience, articulates a penetrating question, sometimes with a joke mixed in, and barely takes the time to listen to the clumsily phrased reply of his opponent. Since English speakers dominate every discussion, they form a class of great minds strutting around in the secure knowledge that no one will challenge them.

Rousseau Meets Japanese Primatology

Frans B. M. De Waal, March 15, 2010

Linguistic Imperialism

The dominance of English can be explained in two ways. First, English is now a required secondary language in most countries throughout the world. The current generation of physicians grew up with an intimate knowledge of English. At the same time, many speakers from Anglophone countries are linguistically lazy, being reluctant to become fluent (or even try to communicate) in any other language. Sadly, many American tourists arrogantly assume that everyone in a major European city speaks English (or should!).

In the past, English was not the language of medical or scientific communication. In the 16th and 17th centuries, scientific works (including those carried out by Englishmen) were never presented for the first time in English. In 1600, the English physician William Gilbert published his seminal work on magnetism in Latin. In 1628, William Harvey published his work on the circulation of the blood in Latin, although it carried a dedication to King Charles I of England. The English physicians Francis Glisson and William Briggs published their seminal work on the liver and the eye, respectively, in Latin (in 1654 and 1685). In 1687, Isaac Newton published the first edition of his Principia in Latin.

However, as the British imperialism spread, the rules changed. A pivotal event occurred in 1685, when Govert Bidloo, a famed Dutch anatomist, published his landmark atlas. In one of the greatest acts of plagiarism in the history of medicine, in 1698, William Cowper (a leading English physician) usurped his anatomical plates and appended English text, without ever acknowledging Bidloo. The plagiarism caused a horrific uproar within the European medical community. Yet, despite overwhelming evidence of intellectual theft, Cowper never apologized -- and never paid a reputational price for his arrogance. For the first time, someone who wrote in English no longer needed to acknowledge the existence of -- let alone their debt to -- someone who wrote in a different language.

The linguistic arrogance of Anglophones grew outrageously over the next 300 years, fostered by the vast expansion of the British Empire. That arrogance exploded following the American victories in World War II, and the dominance of British and American popular culture in the post-war era. When the European Heart Journal (the ESC's official journal) was launched in 1980, its official language was English, even though it was positioned initially as the Continental alternative to the British Heart Journal.

Physicians throughout the world will tell you that they do not mind communicating in English. At an international meeting, a physician from Spain truly prefers to give her talk in English than in German or French. As a result, those of us who hail from native English-speaking countries have enjoyed an enormous -- but wholly undeserved -- privilege. And we take it for granted every single day.

Milton Packer in "The Arrogance of the English Language in Medical Communications"

September 19, 2018 in MedPage Today

What English Sounds Like to Non-English Speakers

|

|

|