- Home

- Process Worldview

- Community

- Art and Music

- Whitehead and Process Thinking

- Podcasts

- Spirituality

- Ecological Civilization

- Education

- Contact

- Social Justice

- Science

- Animals

- Sacred Poems

- Whitehead Videos

- Index of All Titles

- Practicing Process Thought

- Process Spirituality: A Spiritual Alphabet

- Recent Posts

Reading Whitehead

in an Octavian Way

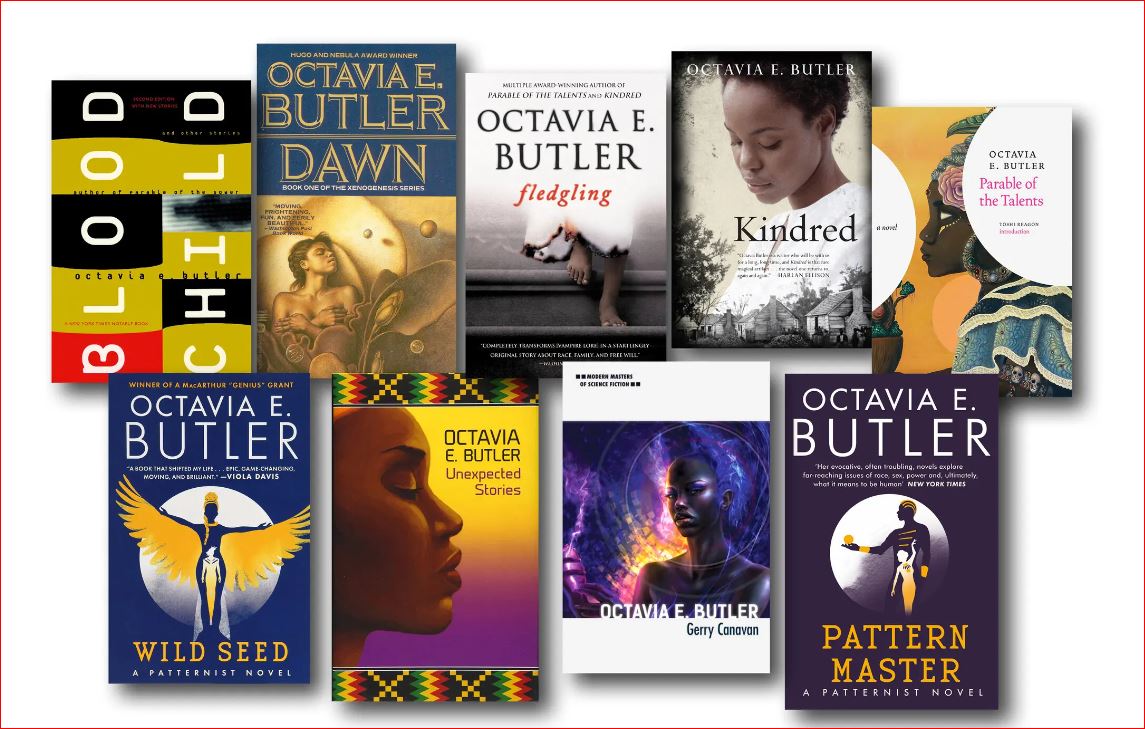

Octavia Butler inspires countless numbers of people around the world. Needless to say, she does this quite apart from any connections her ideas and stories might have with the philosophy of Alfred North Whitehead. Nevertheless, given her power as an author, she can also inspire people to read Whitehead's Process and Reality in an Octavian way: not as a literal map of reality, but as an essay in speculative fiction, exploring possible ways of understanding the world. Whereas characters in Butler's fiction are people and other sentient beings, characters in Whitehead's philosophy are ideas. But both the characters and the stories are, in Whitehead's words, "lures for feeling" and both tell stories. Ideas, after all, tell stories, too. Stories about what might be the case, even if not actually the case. Characters do the same.

Sometimes Butler's stories and Whitehead's stories overlap. Both emphasize process or change, the intrinsic value of life, the interconnectedness of all things, and the damage done when authoritarian approaches to life hold sway. What is important, however, is to understand Butler's and Whitehead's work as stories: not objects to cling to, as if they were infallible dogmas, but evocations for wise, compassionate, and resilient living in challenging times. This page offers springboards for thought about Butler and Whitehead.

*

For a consideration of the relevance of Butler in her own right, I recommend her books, of course, along with the podcast series called Octavia Tried to Tell Us, co-hosted by Tananarive Due and Monica A. Coleman—prominent Black authors with specialties in horror and theology, respectively, along with six books they recommend:

A Handful of Earth, A Handful of Sky: The World of Octavia Butler

By Lynell George

Octavia's Brood: Science Fiction Stories from Social Justice Movements

By Walidah Imarisha and adrienne maree brown

Luminescent Threads: Connections to Octavia E. Butler

By Alexandra Pierce and Mimi Mondal

Conversations With Octavia Butler

By Consuela Francis

Changing Bodies in the Fiction of Octavia Butler: Slaves, Aliens, and Vampires

By Gregory Jerome Hampton

Strange Matings: Science Fiction, Feminism, African American Voices, and Octavia E. Butler

By Rebecca J. Holden and Nisi Shawl

I also recommend the BBC podcast below, featuring Irenosen Okojie, the scholar Gerry Canavan, and Nisi Shawl, writer, editor, journalist – and long-time friend of Octavia Butler. And, of course, the 2005 interview with Octavia Butler below along with her books. And for a consideration of Whitehead's ideas, scroll down for a list of twenty key ideas at the bottom of this page.

Whitehead as Speculative Fiction

Science fiction is speculative fiction. Whitehead's cosmology is speculative cosmology. It is possible and desirable to imagine Whitehead's philosophy as a form of speculative fiction. A philosophical version of ideas found in Octavio Butler's Parable of the Sower, but not quite as interesting.

*

In Plato's "Timaeus," the leading speaker describes the account he is about to give as a “likely account” (eikôs logos) or “likely story” (eikôs muthos). By this, he means that the story he is about to tell, about how the demiurge (a finite deity) forms the world, is, to his mind, plausible but not certain. However, the image of cosmology, whether Plato's or anyone else's, as a likely story invites us to consider the possibility that all cosmologies, even the most informed and complex, are, in fact, stories. Perhaps likely, but still stories. The account of "reality" Whitehead offers in "Process and Reality" is such a story.

*

Sometimes, when I am reading Whitehead's "Process and Reality," I interpret it as a form of speculative fiction, not unlike a really good novel by Octavia Butler or J.R.R. Tolkien. It explores truths of possibility that may or may not correspond to the world of actual facts but are interesting in their own right and challenge existing assumptions and expectations. When read as speculative philosophy, his philosophy takes its place alongside other genres of speculative fiction: science fiction, fantasy fiction, horror, alternative history, and dystopian fiction. Whitehead finds his place alongside authors like Butler, Tolkien, George Orwell, and Margaret Atwood.

Interestingly, Whitehead describes his own philosophy as "speculative philosophy." He acknowledges that it is but a likely story concerning what the world is like, much like Plato in the "Timaeus" speaks of his own account of the origins of the world as such a story. Given the speculative nature of his philosophy, Whitehead asserts that any hint of dogmatic certainty about the finality of a statement is an exhibition of folly. He writes:

"There remains the final reflection, how shallow, puny, and imperfect our efforts are to sound the depths in the nature of things. In philosophical discussion, the merest hint of dogmatic certainty as to the finality of a statement is an exhibition of folly."

It seems to me that if those of us influenced by Whitehead read his philosophy as speculative fiction, we might better avoid the folly of which he speaks. We may find many of his ideas plausible and helpful, but we should hold onto them with a relaxed grasp, knowing that the depths in the nature of things may elude his ideas altogether or be of a very different order. His ideas are best understood as plausible possibilities, but nothing more. The world always transcends his ideas.

*

Whitehead's philosophy invites an appreciation of truths of possibility, even if they do not correspond to the world of actuality. He writes: "In the real world, it is more important that a proposition be interesting than that it be true. The importance of truth is that it adds to interest." In Whitehead's philosophy, a proposition is an idea that functions, in his words, as a "lure for feeling." In a Whiteheadian context, feeling includes acts of thinking, imagining, remembering. Whitehead's philosophy is exactly this. An invitation to think about and imagine the cosmos in an organic way.

*

Many people who are influenced by Whitehead do not think of his philosophy as fiction. They think of it as a conceptual cartography, a map, intended to re-present the actual world or, to be more accurate, the actual multiverse. They believe that its general principles can function as guidelines for living in the world. His ideas can help us recognize the world as an interconnected, evolving whole, in which all entities are present in one another, imbued with intrinsic value (value for themselves), and advancing into an indeterminate future, guided but not controlled by a healing and creative spirit. They believe that even this spirit is in a process of change. God is temporal, they say.

But is this not also a story? Indeed, isn't it a story not unlike what we sometimes find, told more brilliantly, in novels by Octavia Butler and others. Maybe a likely story, but a story. The characters in Whitehead's story are abstract ideas, whereas the characters in Butler's fiction are people who have ideas.

- Jay McDaniel

*

In Plato's "Timaeus," the leading speaker describes the account he is about to give as a “likely account” (eikôs logos) or “likely story” (eikôs muthos). By this, he means that the story he is about to tell, about how the demiurge (a finite deity) forms the world, is, to his mind, plausible but not certain. However, the image of cosmology, whether Plato's or anyone else's, as a likely story invites us to consider the possibility that all cosmologies, even the most informed and complex, are, in fact, stories. Perhaps likely, but still stories. The account of "reality" Whitehead offers in "Process and Reality" is such a story.

*

Sometimes, when I am reading Whitehead's "Process and Reality," I interpret it as a form of speculative fiction, not unlike a really good novel by Octavia Butler or J.R.R. Tolkien. It explores truths of possibility that may or may not correspond to the world of actual facts but are interesting in their own right and challenge existing assumptions and expectations. When read as speculative philosophy, his philosophy takes its place alongside other genres of speculative fiction: science fiction, fantasy fiction, horror, alternative history, and dystopian fiction. Whitehead finds his place alongside authors like Butler, Tolkien, George Orwell, and Margaret Atwood.

Interestingly, Whitehead describes his own philosophy as "speculative philosophy." He acknowledges that it is but a likely story concerning what the world is like, much like Plato in the "Timaeus" speaks of his own account of the origins of the world as such a story. Given the speculative nature of his philosophy, Whitehead asserts that any hint of dogmatic certainty about the finality of a statement is an exhibition of folly. He writes:

"There remains the final reflection, how shallow, puny, and imperfect our efforts are to sound the depths in the nature of things. In philosophical discussion, the merest hint of dogmatic certainty as to the finality of a statement is an exhibition of folly."

It seems to me that if those of us influenced by Whitehead read his philosophy as speculative fiction, we might better avoid the folly of which he speaks. We may find many of his ideas plausible and helpful, but we should hold onto them with a relaxed grasp, knowing that the depths in the nature of things may elude his ideas altogether or be of a very different order. His ideas are best understood as plausible possibilities, but nothing more. The world always transcends his ideas.

*

Whitehead's philosophy invites an appreciation of truths of possibility, even if they do not correspond to the world of actuality. He writes: "In the real world, it is more important that a proposition be interesting than that it be true. The importance of truth is that it adds to interest." In Whitehead's philosophy, a proposition is an idea that functions, in his words, as a "lure for feeling." In a Whiteheadian context, feeling includes acts of thinking, imagining, remembering. Whitehead's philosophy is exactly this. An invitation to think about and imagine the cosmos in an organic way.

*

Many people who are influenced by Whitehead do not think of his philosophy as fiction. They think of it as a conceptual cartography, a map, intended to re-present the actual world or, to be more accurate, the actual multiverse. They believe that its general principles can function as guidelines for living in the world. His ideas can help us recognize the world as an interconnected, evolving whole, in which all entities are present in one another, imbued with intrinsic value (value for themselves), and advancing into an indeterminate future, guided but not controlled by a healing and creative spirit. They believe that even this spirit is in a process of change. God is temporal, they say.

But is this not also a story? Indeed, isn't it a story not unlike what we sometimes find, told more brilliantly, in novels by Octavia Butler and others. Maybe a likely story, but a story. The characters in Whitehead's story are abstract ideas, whereas the characters in Butler's fiction are people who have ideas.

- Jay McDaniel

Points of Contact between

Whitehead and Butler

- Change and Process: Both Whitehead and Butler were interested in the concept of change and process. Whitehead's process philosophy emphasizes that reality is characterized by a continuous process of becoming, and Butler often explored themes of transformation and change in her science fiction works, especially in her "Patternist" series.

- Interconnectedness: Whitehead's philosophy stressed the interconnectedness of all things. Similarly, Butler's works often depicted interconnectedness, whether through telepathic links in "Patternmaster" or through the idea of shared memories in "Kindred."

- Agency and Responsibility: Whitehead's process philosophy includes the idea of agency and responsibility in shaping the future. Butler's characters frequently grapple with issues of agency and responsibility, particularly in the face of challenging circumstances or oppressive systems.

- Speculative Fiction: While Whitehead focused on philosophy and mathematics, he was open to speculative thinking and creative exploration of ideas. Butler's science fiction writing, including her exploration of dystopian futures and alternate realities, can be seen as a form of speculative philosophy.

Octavia Butler's Kindred

Arts & Ideas

A hermit in the middle of Los Angeles" is one way she described herself - born in 1947, Butler became a writer who wanted to "tell stories filled with facts. Make people touch and taste and know." Since her death in 2006, her writing has been widely taken up and praised for its foresight in suggesting developments such as big pharma and for its critique of American history. Shahidha Bari is joined by the author Irenosen Okojie and the scholar Gerry Canavan and Nisi Shawl, writer, editor, journalist – and long-time friend of Octavia Butler.

Irenosen Okojie's latest collection of short stories is called Nudibranch and she was winner of the 2020 AKO Caine Prize for Fiction for her story Grace Jones. You can hear her discussing her own writing life alongside Nadifa Mohamed in a previous Free Thinking episode. Click here. Gerry Canavan is co-editor of The Cambridge Companion to American Science Fiction. Nisi Shawl writes about books for The Seattle Times, and also contributes frequently to Ms. Magazine, The Cascadia Subduction Zone, The Washington Post.

The Metaphysical Status

of Characters in Novels

Propositions a Lures for Feeling

"A proposition has neither the particularity of a feeling, nor the reality of a nexus. It is at datum for feeling, awaiting a subject feeling it. Its relevance to the actual world by means of its logical subjects makes it a lure for feeling. In fact many subjects may feel it with diverse feelings, and with diverse sorts of feelings. were first considered in connection with logic, and the moralistic preference for true propositions, have obscured the rôle of propositions in the actual world. Logicians only discuss the judgment of propositions. Indeed some philosophers fail to distinguish propositions from judgments; and most logicians consider propositions as merely appanages to judgments. The result is that false propositions have fared badly, thrown into the dustheap, neglected. But in the real world it is more important that a proposition be interesting than that it be true. The importance of truth is, that it adds to interest." (Whitehead, Alfred North. Process and Reality)

This paragraph from Whitehead can be rewritten as a description of a character in a novel or, for that matter, in a film. Or as a narrative voice in a poem, or as an idea shared by another person, whether true or false: the idea in a joke, for example. All are propositions or “proposals” which, as experienced, function evocatively as lures for feeling.

Characters in Speculative Fiction as Propositions (Lures for Feeling)

A character in speculative fiction is neither the particularity of a feeling, nor the reality of a public matter of fact such as a boulder or sidewalk, physically felt...It is a datum for feeling, awaiting a subject feeling it…It is a lure for feeling. In fact many readers may feel this character with diverse feelings, and with diverse sorts of feelings. The fact that propositions were first considered in connection with logic, and the moralistic preference for true propositions, have obscured the rôle of propositions in the actual world…The result is that false propositions have fared badly, thrown into the dustheap, neglected. But in the real world it is more important that a proposition be interesting than that it be true. The importance of truth is, that it adds to interest. The same applies to events that occur in speculative fiction. They, too, are lures for feeling.

"A proposition has neither the particularity of a feeling, nor the reality of a nexus. It is at datum for feeling, awaiting a subject feeling it. Its relevance to the actual world by means of its logical subjects makes it a lure for feeling. In fact many subjects may feel it with diverse feelings, and with diverse sorts of feelings. were first considered in connection with logic, and the moralistic preference for true propositions, have obscured the rôle of propositions in the actual world. Logicians only discuss the judgment of propositions. Indeed some philosophers fail to distinguish propositions from judgments; and most logicians consider propositions as merely appanages to judgments. The result is that false propositions have fared badly, thrown into the dustheap, neglected. But in the real world it is more important that a proposition be interesting than that it be true. The importance of truth is, that it adds to interest." (Whitehead, Alfred North. Process and Reality)

This paragraph from Whitehead can be rewritten as a description of a character in a novel or, for that matter, in a film. Or as a narrative voice in a poem, or as an idea shared by another person, whether true or false: the idea in a joke, for example. All are propositions or “proposals” which, as experienced, function evocatively as lures for feeling.

Characters in Speculative Fiction as Propositions (Lures for Feeling)

A character in speculative fiction is neither the particularity of a feeling, nor the reality of a public matter of fact such as a boulder or sidewalk, physically felt...It is a datum for feeling, awaiting a subject feeling it…It is a lure for feeling. In fact many readers may feel this character with diverse feelings, and with diverse sorts of feelings. The fact that propositions were first considered in connection with logic, and the moralistic preference for true propositions, have obscured the rôle of propositions in the actual world…The result is that false propositions have fared badly, thrown into the dustheap, neglected. But in the real world it is more important that a proposition be interesting than that it be true. The importance of truth is, that it adds to interest. The same applies to events that occur in speculative fiction. They, too, are lures for feeling.

The Essential Octavia Butler

She created vivid new worlds to reveal truths about our own.

Here’s where to start with her books. Click here.

Two Ways of Reading Whitehead

- Reading Whitehead as a Literal Map of Reality: In this interpretation, "Process and Reality" is seen as a representation of reality itself, much like a map represents a geographical territory. Whitehead's book is viewed as a guide that presents general principles and concepts to help readers navigate and understand the actual world. It serves as a tool for explaining and describing reality in abstract and general terms. This perspective emphasizes the role of Whitehead's work in providing a structured framework for comprehending the fundamental nature of reality.

- Reading Whitehead as Speculative Fiction: Alternatively, "Process and Reality" can be approached as a work of speculative fiction. In this view, the book is not necessarily a direct representation of reality but rather a speculative exploration of possible ways of understanding the world. These explorations may include unconventional ideas and perspectives that challenge existing assumptions and beliefs. Whitehead's concepts are seen as thought experiments or imaginative "lures for feeling" that engage readers in considering different possibilities and perspectives on reality. This interpretation highlights the creative and imaginative aspect of Whitehead's philosophical work.

It's important to note that these two ways of reading Whitehead are not necessarily mutually exclusive. Readers may shift between these perspectives while engaging with his texts, or they may choose to approach Whitehead's work through both lenses simultaneously. The duality of these interpretations allows for a nuanced and multifaceted understanding of Whitehead's philosophical contributions, making his ideas both a practical guide and a source of intellectual exploration.

Twenty Key Ideas

in the Process Worldview

by Jay McDaniel

1. Process: The universe is an ongoing process of development and change, never quite the same from moment to moment. Every entity in the universe is best understood as a process of becoming that emerges through its interactions with others. The beings of the world are becomings.

2. Interconnectedness: The universe as a whole is a seamless web of interconnected events, none of which can be completely separated from the others. Everything is connected to everything else and contained in everything else. As Buddhists put it, the universe is a network of inter-being.

3. Continuous Creativity: The universe exhibits a continuous creativity on the basis of which new events come into existence over time which did not exist beforehand. This continuous creativity is the ultimate reality of the universe. Everywhere we look we see it. Even God is an expression of Creativity. Even as God creates, God is also continuously created.

4. Nature as Alive: The natural world has value in itself and all living beings are worthy of respect and care. Rocks and trees, hills and rivers are not simply facts in the world; they are also acts of self-realization. The whole of nature is alive with value. We humans dwell within, not apart from, the Ten Thousand Things. We, too, have value.

5. Ethics: Humans find their fulfillment in living in harmony with the earth and compassionately with each other. The ethical life lies in living with respect and care for other people and the larger community of life. Justice is fidelity to the bonds of relationship. A just society is also a free and peaceful society. It is creative, compassionate, participatory, ecologically wise, and spiritually satisfying - with no one left behind.

6. Novelty: Humans find their fulfillment in being open to new ideas, insights, and experiences that may have no parallel in the past. Even as we learn from the past, we must be open to the future. God is present in the world, among other ways, through novel possibilities. Human happiness is found, not only in wisdom and compassion, but also in creativity.

7. Thinking and Feeling: The human mind is not limited to reasoning but also includes feeling, intuiting, imagining; all of these activities can work together toward understanding. Even reasoning is a form of feeling: that is, feeling the presence of ideas and responding to them. There are many forms of wisdom: mathematical, spatial, verbal, kinesthetic, empathic, logical, and spiritual.

8. Relational Selfhood: Human beings are not skin-encapsulated egos cut off from the world by the boundaries of the skin, but persons-in-community whose interactions with others are partly definitive of their own internal existence. We depend for our existence on friends, family, and mentors; on food and clothing and shelter; on cultural traditions and the natural world. The communitarians are right: there is no "self" apart from connections with others. The individualists are right, too. Each person is unique, deserving of respect and care. Other animals deserve respect and care, too.

9. Complementary Thinking: The process way leans toward both-and thinking, not either-or thinking. The rational life consists not only of identifying facts and appealing to evidence, but taking apparent conflicting ideas and showing how they can be woven into wholes, with each side contributing to the other. In Whitehead’s thought these wholes are called contrasts. To be "reasonable" is to be empirical but also imaginative: exploring new ideas and seeing how they might fit together, complementing one another.

10. Theory and Practice: Theory affects practice and practice affects theory; a dichotomy between the two is false. What people do affects how they think and how they think affects what they do. Learning can occur from body to mind: that is, by doing things; and not simply from mind to body.

11. The Primacy of Persuasion over Coercion: There are two kinds of power – coercive power and persuasive power – and the latter is to be preferred over the former. Coercive power is the power of force and violence; persuasive power is the power of invitation and moral example.

12. Relational Power: This is the power that is experienced when people dwell in mutually enhancing relations, such that both are “empowered” through their relations with one another. In international relations, this would be the kind of empowerment that occurs when governments enter into trade relations that are mutually beneficial and serve the wider society; in parenting, this would be the power that parents and children enjoy when, even amid a hierarchical relationship, there is respect on both sides and the relationship strengthens parents and children.

13. The Primacy of Particularity: There is a difference between abstract ideas that are abstracted from concrete events in the world, and the events themselves. The fallacy of misplaced concreteness lies in confusing the abstractions with the concrete events and focusing more on the abstract than the particular.

14. Experience in the Mode of Causal Efficacy: Human experience is not restricted to acting on things or actively interpreting a passive world. It begins by a conscious and unconscious receiving of events into life and being causally affected or influenced by what is received. This occurs through the mediation of the body but can also occur through a reception of the moods and feelings of other people (and animals).

15. Concern for the Vulnerable: Humans are gathered together in a web of felt connections, such that they share in one another’s sufferings and are responsible to one another. Humans can share feelings and be affected by one another’s feelings in a spirit of mutual sympathy. The measure of a society does not lie in questions of appearance, affluence, and marketable achievement, but in how it treats those whom Jesus called "the least of these" -- the neglected, the powerless, the marginalized, the otherwise forgotten.

16. Evil: “Evil” is a name for debilitating suffering from which humans and other living beings suffer, and also for the missed potential from which they suffer. Evil is powerful and real; it is not merely the absence of good. “Harm” is a name for activities, undertaken by human beings, which inflict such suffering on others and themselves, and which cut off their potential. Evil can be structural as well as personal. Systems -- not simply people -- can be conduits for harm.

17. Education as a Lifelong Process: Human life is itself a journey from birth (and perhaps before) to death (and perhaps after) and the journey is itself a process of character development over time. Formal education in the classroom is a context to facilitate the process, but the process continues throughout a lifetime. Education requires romance, precision, and generalization. Learning is best when people want to learn.

18. Religion and Science: Religion and Science are both human activities, evolving over time, which can be attuned to the depths of reality. Science focuses on forms of energy which are subject to replicable experiments and which can be rendered into mathematical terms; religion begins with awe at the beauty of the universe, awakens to the interconnections of things, and helps people discover the norms which are part of the very make-up of the universe itself.

19. God: The universe unfolds within a larger life – a love supreme – who is continuously present within each actuality as a lure toward wholeness relevant to the situation at hand. In human life we experience this reality as an inner calling toward wisdom, compassion, and creativity. Whenever we see these three realities in human life we see the presence of this love, thus named or not. This love is the Soul of the universe and we are small but included in its life not unlike the way in which embryos dwell within a womb, or fish swim within an ocean, or stars travel throught the sky. This Soul can be addressed in many ways, and one of the most important words for addressing the Soul is "God." The stars and galaxies are the body of God and any forms of life which exist on other planets are enfolded in the life of God, as is life on earth. God is a circle whose center is everywhere and circumference nowhere. As God beckons human beings toward wisdom, compassion, and creativity, God does not know the outcome of the beckoning in advance, because the future does not exist to be known. But God is steadfast in love; a friend to the friendless; and a source of inner peace. God can be conceived as "father" or "mother" or "lover" or "friend." God is love.

20. Faith: Faith is not intellectual assent to creeds or doctrines but rather trust in divine love. To trust in love is to trust in the availability of fresh possibilities relative to each situation; to trust that love is ultimately more powerful than violence; to trust that even the galaxies and planets are drawn by a loving presence; and to trust that, no matter what happens, all things are somehow gathered into a wider beauty. This beauty is the Adventure of the Universe as One.

Explanation:

Process thinking is an attitude toward life emphasizing respect and care for the community of life. It is concerned with the well-being of individuals and also with the common good of the world, understood as a community of communities of communities. It sees the world as a process of becoming and the universe as a vast network of inter-becomings. It sees each living being on our planet as worthy of respect and care.

People influenced by process thinking seek to live lightly on the earth and gently with others, sensitive to the interconnectedness of all things and delighted by the differences. They believe that there are many ways of knowing the world -- verbal, mathematical, aesthetic, empathic, bodily, and practical - and that education should foster creativity and compassion as well as literacy.

Process thinkers belong to many different cultures and live in many different regions of the world: Africa, Asia, Latin America, Europe, North America, and Oceania. They include teenagers, parents, grandparents, store-clerks, accountants, farmers, musicians, artists, and philosophers.

Many of the scholars in the movement are influenced by the perspective of the late philosopher and mathematician, Alfred North Whitehead. His thinking embodies the leading edge of the intellectual side of process thinking. Nevertheless, a mastery of his ideas is not necessary to be a process thinker. Ultimately process thinking is an attitude and outlook on life, and a way of interacting with the world. It is not so much a rigidly-defined worldview as it is a way of feeling the presence of the world and responding with creativity and compassion.

The tradition of process thinking can be compared to a growing and vibrant tree, with blossoms yet to unfold. The roots of the tree are the many ideas developed by Whitehead in his mature philosophy. They were articulated most systematically in his book Process and Reality: An Essay in Cosmology. The trunk consists of more general ideas which have been developed by subsequent thinkers from different cultures, adding creativity of their own. These general ideas flow from Whitehead's philosophy, but are less technical in tone. The branches consist of the many ways in which these ideas are being applied to daily life and community development. The branches include applications to a wide array of topics, ranging from art and music to education and ecology.

Much of this website -- Open Horizons - is devoted to the branches and trunk. Of course, some people will be interested in the roots. For those interested in gaining knowledge of the roots, we have created a free course of short videos which provides an introduction to Alfred North Whitehead's organic philosophy and serves as a guiding companion to Whitehead's seminal work, Process and Reality. These twenty six-minute videos are offered below. They can be viewed in sequence or in parts, depending on your interests. If you would like to get started on this short course to better understand the roots of process thinking, go to What is Process Thought? The ideas above represent the twenty key ideas in the trunk.