On Being Kings and Queens

for an Ecological Civilization

A Brief Exploration of a Chinese Character

John Becker, Ph.D.

(3/17/2019)

Several years ago, I started studying classical Chinese in order to engage fruitfully traditional Chinese thought and Buddhism in East Asia. As with learning any new language, the task is daunting. The difficulty is compounded, however, when working between culturally different modes of linguistic expression: the alphabetic and logographic systems. Whereas alphabetic systems of writing are decipherable only through the cultures that gave rise to them, logographic languages are imbued with universal quality.

For example, the word “mountain” derives its meaning from the arrangement of the letters as it operates within a particular system of language: English. Outside the context of this system, it remains undecipherable. Chinese logography is similarly a system but more ambiguous and less ridged. With some intuitive thought, the Chinese character for mountain (山) visually suggests the thing being signified. Looking at the character, one can envision a tall peak in the middle with two descended peaks on the side.

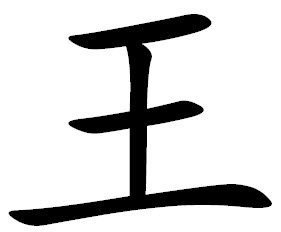

My point is that logographic systems are not entirely closed systems as alphabetic systems. There is a universal quality captured in logograms that are lacking other writing systems. What follows is a Westerner’s appropriation of a crucially important classical character in Chinese thought: “King” (王). My goal is to offer an ecologically infused commentary on its rich symbolism and demonstrate its use for an ecologically oriented person.

The role of the King in Chinese culture (王) has been a topic of conversation since times immemorial. The state of the people, the environment, and the world were all directly related to the conduct of the King. The character for King speaks directly to these concerns: The top horizontal line represents the heavens, the middle horizontal line represents society, and the bottom horizontal line represents the earth. This trifold scheme reveals a cosmological pattern in Chinese thought. The heavens and the earth create a blueprint for society to replicate as they come to represent the natural order. The vertical line that intersects the trifold cosmos represents the King. Kings bring the heavens, society, and nature into accord with one another: They act as the all-important conduits that bring the tiers into a relational whole.

The King’s cosmic duty is made evident through the Mandate of Heaven (天命), a religio-political concept that justified a King’s legitimate reign or usurpation. If the kings did not align themselves to the law of heaven, the needs of society, or the reverence of the life-giving nature of the environment, the different layers would revolt against the throne in various forms, whether floods, fires, plagues, social unrest, famines, and so forth. The King’s duty, then, is to the world in its entirety, seeking to integrate the heavens, society, and earth harmoniously. To isolate any one over the other would inevitably bring about discord between the strata, and thus give rise to a chaos and turmoil. A balanced approached to the tiers are vital not only for a vibrant world but a holistic, dignified person.

The King character (王) is useful in thinking about an individual’s duty as a world citizen because it is teeming with cosmological significance. We are all called to be “Kings” and “Queens,” to find a balance that humbly situates us between the heavens and earth. Today we encounter different modes of life that are hyper-localized on only one tier of the ancient Chinese universe, highlighting various aspects of religion, society, and the environment. This unnaturally compartmentalizes our world while failing to recognize our expanded duties. The Chinese character invites us to see beyond our limitations and makes us to acknowledge our cosmic obligations.

The character also draws our attention to the individual. The vertical line is not diminished by the cosmic order, but a process of self-identity instigated through these relational tiers. While the heavens and earth act accordingly to their inherent nature, the individual, as a unit of society, is to actively participate in the creation of an equitable, loving community. Within a Confucian context, to cultivate the individual is to simultaneously improve the family, society, and beyond. The vertical line, then, vibrates throughout the cosmic order, a microcosm influencing the larger cosmos. If we all took our cosmic duties seriously by navigating our trifold responsibilities honestly and faithfully, it seems that an ecological civilization would no longer be a hope waiting for actualization, but reality already present.

This intellectual musing is admittedly abstract and perhaps too creative for sinologist (the academic study of China), but the character for “King” proves to be a powerful ecological motif. In terms of the Chinese language, “King” is extremely simple, consisting of 4 straight strokes (王), yet these four strokes speak of an individual’s obligation to the universe. It is a beautiful reminder of the cosmic demands on an individual and urges us to accept the call to be Kings and Queens for an Ecological Civilization.

For example, the word “mountain” derives its meaning from the arrangement of the letters as it operates within a particular system of language: English. Outside the context of this system, it remains undecipherable. Chinese logography is similarly a system but more ambiguous and less ridged. With some intuitive thought, the Chinese character for mountain (山) visually suggests the thing being signified. Looking at the character, one can envision a tall peak in the middle with two descended peaks on the side.

My point is that logographic systems are not entirely closed systems as alphabetic systems. There is a universal quality captured in logograms that are lacking other writing systems. What follows is a Westerner’s appropriation of a crucially important classical character in Chinese thought: “King” (王). My goal is to offer an ecologically infused commentary on its rich symbolism and demonstrate its use for an ecologically oriented person.

The role of the King in Chinese culture (王) has been a topic of conversation since times immemorial. The state of the people, the environment, and the world were all directly related to the conduct of the King. The character for King speaks directly to these concerns: The top horizontal line represents the heavens, the middle horizontal line represents society, and the bottom horizontal line represents the earth. This trifold scheme reveals a cosmological pattern in Chinese thought. The heavens and the earth create a blueprint for society to replicate as they come to represent the natural order. The vertical line that intersects the trifold cosmos represents the King. Kings bring the heavens, society, and nature into accord with one another: They act as the all-important conduits that bring the tiers into a relational whole.

The King’s cosmic duty is made evident through the Mandate of Heaven (天命), a religio-political concept that justified a King’s legitimate reign or usurpation. If the kings did not align themselves to the law of heaven, the needs of society, or the reverence of the life-giving nature of the environment, the different layers would revolt against the throne in various forms, whether floods, fires, plagues, social unrest, famines, and so forth. The King’s duty, then, is to the world in its entirety, seeking to integrate the heavens, society, and earth harmoniously. To isolate any one over the other would inevitably bring about discord between the strata, and thus give rise to a chaos and turmoil. A balanced approached to the tiers are vital not only for a vibrant world but a holistic, dignified person.

The King character (王) is useful in thinking about an individual’s duty as a world citizen because it is teeming with cosmological significance. We are all called to be “Kings” and “Queens,” to find a balance that humbly situates us between the heavens and earth. Today we encounter different modes of life that are hyper-localized on only one tier of the ancient Chinese universe, highlighting various aspects of religion, society, and the environment. This unnaturally compartmentalizes our world while failing to recognize our expanded duties. The Chinese character invites us to see beyond our limitations and makes us to acknowledge our cosmic obligations.

The character also draws our attention to the individual. The vertical line is not diminished by the cosmic order, but a process of self-identity instigated through these relational tiers. While the heavens and earth act accordingly to their inherent nature, the individual, as a unit of society, is to actively participate in the creation of an equitable, loving community. Within a Confucian context, to cultivate the individual is to simultaneously improve the family, society, and beyond. The vertical line, then, vibrates throughout the cosmic order, a microcosm influencing the larger cosmos. If we all took our cosmic duties seriously by navigating our trifold responsibilities honestly and faithfully, it seems that an ecological civilization would no longer be a hope waiting for actualization, but reality already present.

This intellectual musing is admittedly abstract and perhaps too creative for sinologist (the academic study of China), but the character for “King” proves to be a powerful ecological motif. In terms of the Chinese language, “King” is extremely simple, consisting of 4 straight strokes (王), yet these four strokes speak of an individual’s obligation to the universe. It is a beautiful reminder of the cosmic demands on an individual and urges us to accept the call to be Kings and Queens for an Ecological Civilization.