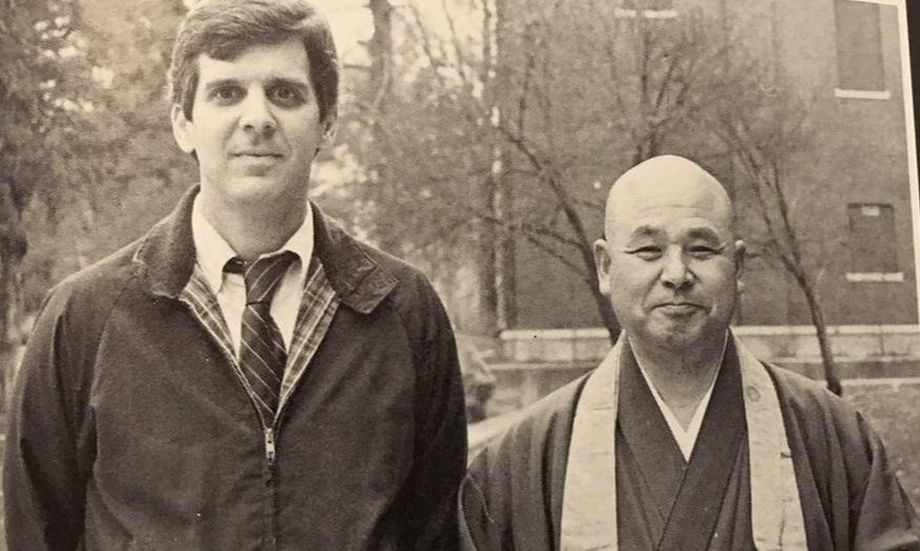

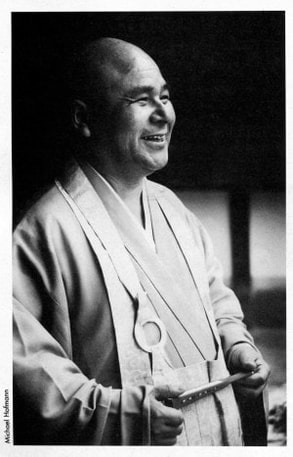

Zen Master Keido Fukushima

On Being the English Teacher

for a Zen Buddhist Master

by Jay McDaniel

I knew the bridge between East and West. He died in 2011 at the age of 78 but I think about him every day. I wrote this before he died but it seems as relevant today as yesterday. I'm still working on my paradoxical Zen question, my koan. If you'd like to know more about his life and teachings, I hope you'll take a look at Zen Bridge: The Zen Teachings of Keido Fukushima and The Laughing Buddha of Tofukuji. But the narrative below can give you a feel for one person's friendship with a living bridge between East and West: Zen Master Keido Fukushima. I think we are both crossing the bridge even now, shaking hands in the middle, with a respectful hug, and him with that twinkling in his eye.

*

I had the privilege of being Keido Fukushima’s English teacher for one full year, when he came to Claremont, California, in 1972. He had been sent by his Master—Roshi Shibayama—not only to brush up on his English so that he could help westerners understand Zen, but also to learn about America itself. For one year, then, I would meet with him and help him with English and also take him to various places in southern California that seemed to me “American.” These ranged from Baskin Robbins ice-cream parlors, through movie theatres where we saw films such as “The Sound of Music,” to Benedictine monasteries where we could see monastic life, Christian style. As we did these things together, I taught him about English and about the United States, and he taught me about Zen. His teachings took many forms, some of which were verbal. I will always remember the first time I met him. I had been taught that in Japan people bow, and he had been taught that in the United States people shake hands, so our first actual encounter was the experience of having his outstretched hand on my forehead. I am sure that we were both a little nervous, but this non-verbal event certainly broke the ice, at least for him. He laughed immediately, and I realized that, whatever Zen was, it was not simply about being serious all the time. It was obedience to the call of the moment, and this moment called for laughter.

After we entered the apartment where he was staying — Blaisdell House— he asked in broken English if I might like some coffee. He had figured out how to make it. As he made the coffee, I thought to myself: What will I say to this Zen priest? After all, it was all new to me. He brought me the coffee, after which I thought I would try to make conversation. I asked him how his trip went, and he answered, “Fine.” Then, for some strange reason, I blurted out, in a deeply serious way: “Tell me, what do you know as a Zen person that I don’t?” I had been reading so much about Buddhism and about nirvana that I figured he knew something I didn’t know, and I wanted him to tell me. Without any hesitation, he said to me: “I know that I am you, and you are me, too. But you don’t know that.” This, then, was a second lesson in Zen for me. It was that obedience to the call of the moment comes from a prior awareness that things aren’t so separate in the first place. We can be outside each other’s bodies, but inside each other’s awareness, and the latter is closer to the real nature of things.

There were many other moments like this. There was the time, for example, when he spotted a black Labrador retriever happily strolling across a yard with a bone in his mouth and oblivious to any artificial conventions. Keido turned to me quickly and said: “Jay, do you see that dog?” I said, “Yes,” and he responded, “That’s a Zen master!” This helped me see that Zen cherishes something deep and spontaneous and natural within the human mind, and that maybe old Joshu’s dog did indeed have the Buddha nature after all. And there was the time when, after we got up from a table and walked to the door of a room where we were sitting, he looked back where he had been sitting and said: “Jay, do you remember that Zen priest back there?” I said, “Yes,” and he pointed to himself at that moment and said, “New Zen priest!” This helped me see that Zen is about every moment being a new moment.

And then there was the zazen itself, when I would sit with Keido, somehow feeling the strength of his own sitting, and somehow feeling a pipeline between him and the others who were sitting, filled with contagious silence. These moments, too, were teachings, albeit in a more “letting go” way. But then again, almost all the things I did with my “student” were teachings for me, and now, so many years later, I find my mind filled with such memories. Added to them, though, is the fact that we have remained friends ever since, and that we see each other once a year, when he visits the college where I teach. And added to them is the retreat he leads, in which I am a participant, amid which I do dokusan with him (the asking and responding to Zen questions). Of course, I am not sure I will ever truly know the sound of one hand clapping. I’m not sure I’ll ever clap back in just the right way. But what is so clear to me, even now, is that there is a rather deep friendship between the two of us that transcends many, many dualisms, including that of him being “Buddhist” and me being “Christian.” I will always appreciate that, in this friendship, I never for a moment sensed that I was supposed to become Buddhist in order to learn from him and with him. Nor do I to this day. Our relationship runs much deeper than Buddhist-Christian dialogue. It is Buddhist-Christian friendship, and beyond that, too. Just friends ... like old dogs, running across a lawn, each with his bone.

This reminiscence was originally published in The Laughing Buddha of Tofukuji by Ishwar Harris

*

I had the privilege of being Keido Fukushima’s English teacher for one full year, when he came to Claremont, California, in 1972. He had been sent by his Master—Roshi Shibayama—not only to brush up on his English so that he could help westerners understand Zen, but also to learn about America itself. For one year, then, I would meet with him and help him with English and also take him to various places in southern California that seemed to me “American.” These ranged from Baskin Robbins ice-cream parlors, through movie theatres where we saw films such as “The Sound of Music,” to Benedictine monasteries where we could see monastic life, Christian style. As we did these things together, I taught him about English and about the United States, and he taught me about Zen. His teachings took many forms, some of which were verbal. I will always remember the first time I met him. I had been taught that in Japan people bow, and he had been taught that in the United States people shake hands, so our first actual encounter was the experience of having his outstretched hand on my forehead. I am sure that we were both a little nervous, but this non-verbal event certainly broke the ice, at least for him. He laughed immediately, and I realized that, whatever Zen was, it was not simply about being serious all the time. It was obedience to the call of the moment, and this moment called for laughter.

After we entered the apartment where he was staying — Blaisdell House— he asked in broken English if I might like some coffee. He had figured out how to make it. As he made the coffee, I thought to myself: What will I say to this Zen priest? After all, it was all new to me. He brought me the coffee, after which I thought I would try to make conversation. I asked him how his trip went, and he answered, “Fine.” Then, for some strange reason, I blurted out, in a deeply serious way: “Tell me, what do you know as a Zen person that I don’t?” I had been reading so much about Buddhism and about nirvana that I figured he knew something I didn’t know, and I wanted him to tell me. Without any hesitation, he said to me: “I know that I am you, and you are me, too. But you don’t know that.” This, then, was a second lesson in Zen for me. It was that obedience to the call of the moment comes from a prior awareness that things aren’t so separate in the first place. We can be outside each other’s bodies, but inside each other’s awareness, and the latter is closer to the real nature of things.

There were many other moments like this. There was the time, for example, when he spotted a black Labrador retriever happily strolling across a yard with a bone in his mouth and oblivious to any artificial conventions. Keido turned to me quickly and said: “Jay, do you see that dog?” I said, “Yes,” and he responded, “That’s a Zen master!” This helped me see that Zen cherishes something deep and spontaneous and natural within the human mind, and that maybe old Joshu’s dog did indeed have the Buddha nature after all. And there was the time when, after we got up from a table and walked to the door of a room where we were sitting, he looked back where he had been sitting and said: “Jay, do you remember that Zen priest back there?” I said, “Yes,” and he pointed to himself at that moment and said, “New Zen priest!” This helped me see that Zen is about every moment being a new moment.

And then there was the zazen itself, when I would sit with Keido, somehow feeling the strength of his own sitting, and somehow feeling a pipeline between him and the others who were sitting, filled with contagious silence. These moments, too, were teachings, albeit in a more “letting go” way. But then again, almost all the things I did with my “student” were teachings for me, and now, so many years later, I find my mind filled with such memories. Added to them, though, is the fact that we have remained friends ever since, and that we see each other once a year, when he visits the college where I teach. And added to them is the retreat he leads, in which I am a participant, amid which I do dokusan with him (the asking and responding to Zen questions). Of course, I am not sure I will ever truly know the sound of one hand clapping. I’m not sure I’ll ever clap back in just the right way. But what is so clear to me, even now, is that there is a rather deep friendship between the two of us that transcends many, many dualisms, including that of him being “Buddhist” and me being “Christian.” I will always appreciate that, in this friendship, I never for a moment sensed that I was supposed to become Buddhist in order to learn from him and with him. Nor do I to this day. Our relationship runs much deeper than Buddhist-Christian dialogue. It is Buddhist-Christian friendship, and beyond that, too. Just friends ... like old dogs, running across a lawn, each with his bone.

This reminiscence was originally published in The Laughing Buddha of Tofukuji by Ishwar Harris