- Home

- Process Worldview

- Community

- Art and Music

- Whitehead and Process Thinking

- Podcasts

- Spirituality

- Ecological Civilization

- Education

- Contact

- Social Justice

- Science

- Animals

- Sacred Poems

- Whitehead Videos

- Index of All Titles

- Practicing Process Thought

- Process Spirituality: A Spiritual Alphabet

- Recent Posts

Why it Matters

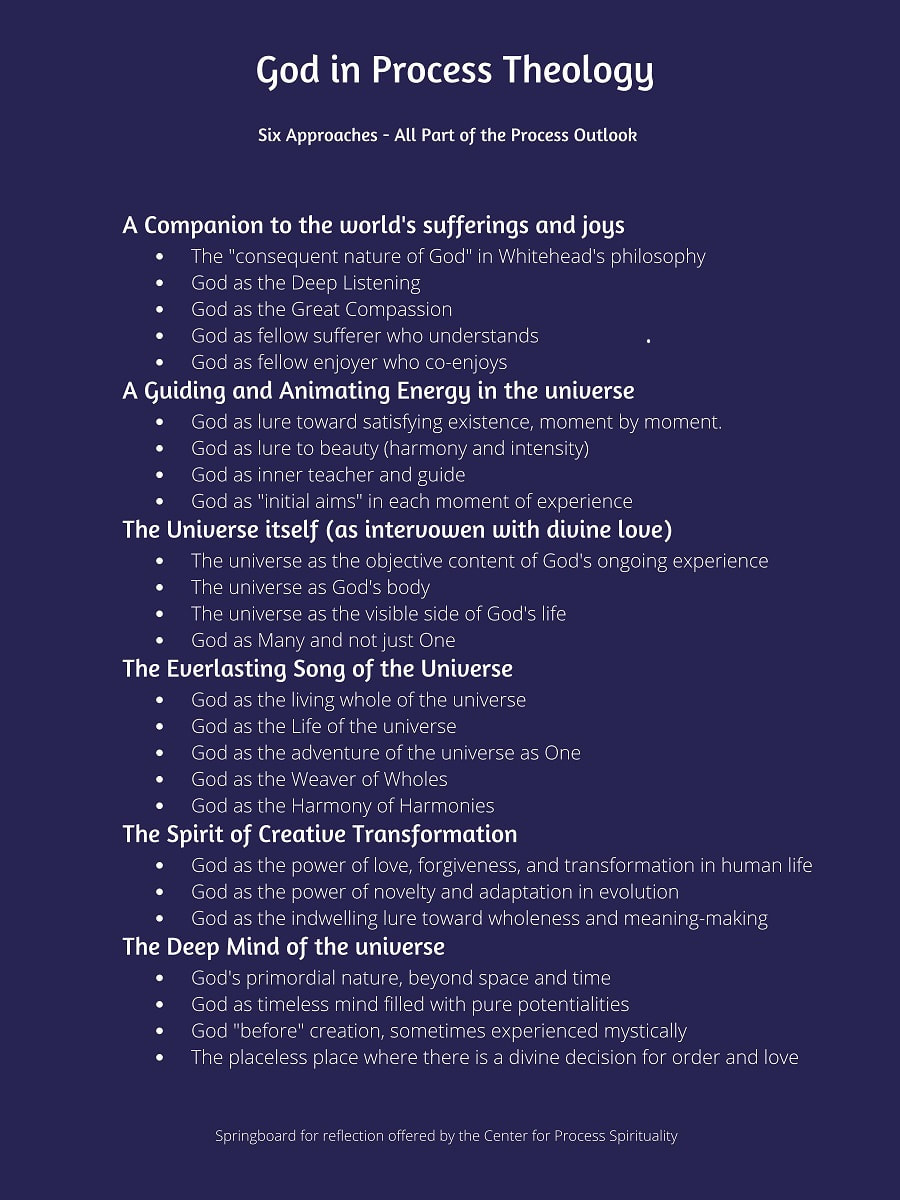

Process philosophies and theologies offer a unique way of thinking about God which we believe can be embraced by Muslims and Christians alike. The way is neither philosophical to the exclusion of theology, nor theological to the exclusion of philosophy. It is instead a form of philosophical theology that integrates the wisdo of reason and faith.

Today Muslims and Christians together form more than fifty percent of the world's population. We do not say this with pride; to the contrary we celebrate the multitude of religions on the planet. We want a religiously diverse world, and we repudiate the idea that the whole world ought to be either Muslim or Christian. We agree with the Qur'an that the plurality is itself desired by One whose very heart delights in multiplicity, so that we humans can know one another. Let there be many religions, many cultures, many wisdom paths. And let them include our Jewish sisters and brothers, our Buddhist and Hindu friends, our Daoist and Indigenous cousins in the spirit.

But we recognize that, given our numbers, it truly matters how we think about God. If we think of God in ways that lend themselves to authoritarianism, oppression, and a stifling of human responsibility, it matters to those who are affected. It matters to Christians and Muslims, and it matters to others, too.

Our view is that if we think of God on the analogy of an autocratic ruler who selfishly seeks "his" own pleasure at the expense of the world; and if we think that this divine ruler preordains all that happens even before it happens, such that the world itself lacks agency; and if we think that our task as humans is to passively accept everything that happens (the injustices, the cruelties, the hatreds) is God's will, we will act accordingly. Indeed, we may find ourselves supporting the autocrats of the world because they are servants of the divinely ordained plan. We will miss the opportunity to cooperate with God in helping create a world that is just and sustainable for all. This is why we think it is important to lift up an alternative: the process approach.

We do not pretend that we have got a "lock" on God. We know that the mystery in which we live and move and have our being is more than our understanding of it, not simply because it is so far beyond us, but rather because it may be closer to us, and more merciful, than we ever imagine. Closer than our jugular veins, as the Qur'an puts it. With this in mind we share some of the core ideas of our own shared way of understanding God. In humility, then, but also with a recognition that how we think about God truly counts, we add a process voice to the ongoing, global conversation. We begin with ten key ideas, add two more, returning to the question of divine knowledge, and ending with some textual support from AN Whitehead and John Cobb.

Today Muslims and Christians together form more than fifty percent of the world's population. We do not say this with pride; to the contrary we celebrate the multitude of religions on the planet. We want a religiously diverse world, and we repudiate the idea that the whole world ought to be either Muslim or Christian. We agree with the Qur'an that the plurality is itself desired by One whose very heart delights in multiplicity, so that we humans can know one another. Let there be many religions, many cultures, many wisdom paths. And let them include our Jewish sisters and brothers, our Buddhist and Hindu friends, our Daoist and Indigenous cousins in the spirit.

But we recognize that, given our numbers, it truly matters how we think about God. If we think of God in ways that lend themselves to authoritarianism, oppression, and a stifling of human responsibility, it matters to those who are affected. It matters to Christians and Muslims, and it matters to others, too.

Our view is that if we think of God on the analogy of an autocratic ruler who selfishly seeks "his" own pleasure at the expense of the world; and if we think that this divine ruler preordains all that happens even before it happens, such that the world itself lacks agency; and if we think that our task as humans is to passively accept everything that happens (the injustices, the cruelties, the hatreds) is God's will, we will act accordingly. Indeed, we may find ourselves supporting the autocrats of the world because they are servants of the divinely ordained plan. We will miss the opportunity to cooperate with God in helping create a world that is just and sustainable for all. This is why we think it is important to lift up an alternative: the process approach.

We do not pretend that we have got a "lock" on God. We know that the mystery in which we live and move and have our being is more than our understanding of it, not simply because it is so far beyond us, but rather because it may be closer to us, and more merciful, than we ever imagine. Closer than our jugular veins, as the Qur'an puts it. With this in mind we share some of the core ideas of our own shared way of understanding God. In humility, then, but also with a recognition that how we think about God truly counts, we add a process voice to the ongoing, global conversation. We begin with ten key ideas, add two more, returning to the question of divine knowledge, and ending with some textual support from AN Whitehead and John Cobb.

Ten Key Ideas

in the process understanding of God

1. God's unchanging aim is for beauty understood as richness of experience.

2. God seeks salvation for each and all: universal richness of experience.

3. God is in the world through fresh possibilities or "initial aims."

4. We feel God's feelings and share in God's desires. God is within us.

5. God is both eternal and everlasting: non-temporal and infinitely temporal.

6. God is nowhere and everywhere: non-spatial and omni-spatial.

7. God is lovingly affected by the world: a fellow sufferer who understands.

8. God saves the world through tenderness.

9. God is many as well as one.

10. God recycles love.

2. God seeks salvation for each and all: universal richness of experience.

3. God is in the world through fresh possibilities or "initial aims."

4. We feel God's feelings and share in God's desires. God is within us.

5. God is both eternal and everlasting: non-temporal and infinitely temporal.

6. God is nowhere and everywhere: non-spatial and omni-spatial.

7. God is lovingly affected by the world: a fellow sufferer who understands.

8. God saves the world through tenderness.

9. God is many as well as one.

10. God recycles love.

Two More Ideas

To the ten ideas many process theologians will add two more. For some among them, these two are especially important.

God is not in complete control of the world; God acts through love not domination: One is that God's power in the universe and in human life is persuasive not coercive, invitational not manipulative, loving not combative, which means that God is not all-powerful in the sense that God wills, permits, or could control everything that happens, including tragedies. All of this is entailed in the process view that God acts in the world through fresh possibilities or initial aims. For process theologians there are many things that happen in the world that are genuinely evil. murder, rape, abuse, cruelty, violence, and injustice. Not all things are "meant to be" from a process perspective. God, too, laments and then redeems with the provision of new possibilities.

God knows what is possible in the future, but not what is actual until it is actual: The other is that God knows all that is actual in the past and present but not what is actual in the future until it becomes actual. The future is open even for God, which means that God is indeed all-knowing but in a dynamic way. God knows what is possible in the future, but not what is actual until it becomes actual. God's wisdom about what is important and God's love are changeless, but God's knowledge of what happens in the world grows. This means that prayers to God are heard by God as they are offered not before they are offered, and that the future does not unfold along the lines of an already-known script in God's mind. We humans and other living beings create the script as we act in the world.

Both of these ideas are controversial for many who are steeped in classical, Greek-influenced traditions, whether Christian or Muslim. Today a prominent Christian theologian, Thomas J. Oord, has been especially influential in helping to foster a powerful social movement aimed at promoting these two ideas and critiquing their alternatives: the idea that God acts through controlling power and that the future, as actuality, is already known by God. We might call it the God Can't movement, because it is deeply influenced by Oord's book God Can't. If you are interested in this movement, I suggest you take a look at the work of the Center for Open and Relational Theology and also the Facebook group called Healing with God Can't.

In naming the ten ideas above we are emphasizing what is most prominant in the understandings of God in Whitehead's Process and Reality and John Cobb's A Christian Natural Theology. These two books have been deeply influential in the minds and hearts of many Christian process theologians, and they resonate with an Islamic process perspective as well. Please add these two additional ideas to the list if twelve seems better than ten for any reason.

God is not in complete control of the world; God acts through love not domination: One is that God's power in the universe and in human life is persuasive not coercive, invitational not manipulative, loving not combative, which means that God is not all-powerful in the sense that God wills, permits, or could control everything that happens, including tragedies. All of this is entailed in the process view that God acts in the world through fresh possibilities or initial aims. For process theologians there are many things that happen in the world that are genuinely evil. murder, rape, abuse, cruelty, violence, and injustice. Not all things are "meant to be" from a process perspective. God, too, laments and then redeems with the provision of new possibilities.

God knows what is possible in the future, but not what is actual until it is actual: The other is that God knows all that is actual in the past and present but not what is actual in the future until it becomes actual. The future is open even for God, which means that God is indeed all-knowing but in a dynamic way. God knows what is possible in the future, but not what is actual until it becomes actual. God's wisdom about what is important and God's love are changeless, but God's knowledge of what happens in the world grows. This means that prayers to God are heard by God as they are offered not before they are offered, and that the future does not unfold along the lines of an already-known script in God's mind. We humans and other living beings create the script as we act in the world.

Both of these ideas are controversial for many who are steeped in classical, Greek-influenced traditions, whether Christian or Muslim. Today a prominent Christian theologian, Thomas J. Oord, has been especially influential in helping to foster a powerful social movement aimed at promoting these two ideas and critiquing their alternatives: the idea that God acts through controlling power and that the future, as actuality, is already known by God. We might call it the God Can't movement, because it is deeply influenced by Oord's book God Can't. If you are interested in this movement, I suggest you take a look at the work of the Center for Open and Relational Theology and also the Facebook group called Healing with God Can't.

In naming the ten ideas above we are emphasizing what is most prominant in the understandings of God in Whitehead's Process and Reality and John Cobb's A Christian Natural Theology. These two books have been deeply influential in the minds and hearts of many Christian process theologians, and they resonate with an Islamic process perspective as well. Please add these two additional ideas to the list if twelve seems better than ten for any reason.

Ten Key Ideas with Quotes

from John Cobb and Whitehead

The eternal and unchanging aim of God is to enjoy harmonious intensity, or “strength of beauty.”

Whitehead speaks of God as having, like all actual entities, an aim at intensity of feeling. (PR 160-161.) In terms of the developed value theory of Adventures of Ideas, we may say his aim is at strength of beauty. This aim is primordial and unchanging, and it determines the primordial ordering of eternal objects. (John Cobb in A Christian Natural Theology)

God’s eternal and unchanging aim is not for divine satisfaction alone but for universal satisfaction.

But if this eternal ordering is to have specified efficacy for each new occasion, then the general aim by which it is determined must be specified to each occasion. That is, God must entertain for each new occasion the aim for its ideal satisfaction. Such an aim is the feeling of a proposition of which the novel occasion is the logical subject and the appropriate eternal object is the predicate. The subjective form of the propositional feeling is appetition, that is, the desire for its realization. (John Cobb in A Christian Natural Theology)

In God, however, there are no such tensions because the ideal strength of beauty for himself and for the world coincide. Hence, we may simplify and say that God’s aim is at ideal strength of beauty and that this aim is eternally unchanging... In God’s case there is nothing selfish about the constant aim at his own ideal satisfaction, since this may equally well be described as an aim at universal satisfaction.” (John Cobb in A Christian Natural Theology)

Even as God’s aim for the world is unchanging, the aim is also flexible. It is continuously adapted to changing circumstances. These adaptations, as felt by human beings and other living beings, are the initial aims.

Certainly God’s aim is unchangingly directed to an ideal strength of beauty. In this unchanging form it must be indifferent to how this beauty is attained. But if God’s aim at beauty explains the limitation by which individual occasions achieve definiteness, then in its continual adaptation to changing circumstances it must involve propositional feelings of each of the becoming occasions as realizing some peculiar satisfaction. God’s subjective aim will then be so to actualize himself in each moment that the propositional feeling he entertains with respect to each new occasion will have maximum chance of realization. (John Cobb in A Christian Natural Theology)

In the initial phase of our subjective aims for ourselves, we feel God’s feelings and want for ourselves what God wants for us.

Every occasion then prehends God’s prehension of this ideal for it, and to some degree the subjective form of its prehension conforms to that of God. That means that the temporal occasion shares God’s appetition for the realization of that possibility in that occasion. Thus, God’s ideal for the occasion becomes the occasion’s ideal for itself, the initial phase of its subjective aim. (John Cobb in A Christian Natural Theology)

God is both timeless and infinitely temporal, eternal and everlasting.

For Whitehead, "time" is physical time, and it is "perpetual perishing." The primordial nature of God is eternal. This means that it is wholly unaffected by time or by process in any other sense. The primordial nature of God affects the world but is unaffected by it. For it, before and after are strictly irrelevant categories. (John Cobb in A Christian Natural Theology)

The consequent nature of God is "everlasting." This means that it involves a creative advance, just as time does, but that the earlier elements are not lost as new ones are added. Whatever enters into the consequent nature of God remains there forever, but new elements are constantly added. Viewed from the vantage point of Whitehead’s conclusion and the recognition that God is an actual entity in which the two natures are abstract parts, we must say that God as a whole is everlasting, but that he envisages all possibility eternally. (John Cobb in A Christian Natural Theology)

God is everywhere (non-spatial) and nowhere (omni-spatial). There may be many dimensions of space.

It is possible in Whitehead to consider time in some abstraction from space without serious distortion. Successiveness is a relation not dependent upon spatial dimensions for its intelligibility. I understand Whitehead to say that time, in the sense of successiveness, is metaphysically necessary whereas space, or at least anything like what we mean by space, is not. There might be one dimension or a hundred in some other cosmic epoch. Since God would remain unalterably God in any cosmic epoch, his relation to space must be more accidental than his relation to time. (John Cobb in A Christian Natural Theology)

God is an everlasting companion to the world: infinitely patient, tender, and empathic, feeling the feelings of all actualities.

God is the great companion— the fellow-sufferer who understands. (Alfred North Whitehead, Process and Reality)

The ‘consequent nature’ of God is the physical prehension by God of the actualities of the evolving universe. (Alfred North Whitehead, Process and Reality)

It is here termed ‘God’; because the contemplation of our natures, as enjoying real feelings derived from the timeless source of all order, acquires that ‘subjective form’ of refreshment and companionship at which religions aim. (Alfred North Whitehead, Process and Reality)

The consequent nature of God is conscious; and it is the realization of the actual world in the unity of his nature, and through the transformation of his wisdom. The primordial nature is conceptual, the consequent nature is the weaving of God's physical feelings upon his primordial concepts. (Alfred North Whitehead, Process and Reality)

God saves the world through tenderness

The consequent nature of God is his judgment on the world. He saves the world as it passes into the immediacy of his own life. It is the judgment of a tenderness which loses nothing that can be saved. It is also the judgment of a wisdom which uses what in the temporal world is mere wreckage. Another image which is also required to understand his consequent nature† is that of his infinite patience. (Alfred North Whitehead, Process and Reality)

God includes the multiplicity of the world within God’s own everlasting life.

The consequent nature of God is the fluent world become ‘everlasting’ by its objective immortality in God…Thus the consequent nature of God is composed of a multiplicity of elements with individual self-realization. It is just as much a multiplicity as it is a unity; it is just as much one immediate fact as it is an unresting advance beyond itself. (Alfred North Whitehead, Process and Reality)

God recycles. As the world becomes part of God, the “love in heaven” floods back into the world as perpetual refreshment.

The love in the world passes into the love in heaven, and floods back again into the world. In this sense, God is the great companion— the fellow-sufferer who understands. (Alfred North Whitehead, Process and Reality)

In this way, the insistent craving is justified— the insistent craving that zest for existence be refreshed by the ever-present, unfading importance of our immediate actions, which perish and yet live for evermore. (Alfred North Whitehead, Process and Reality)

Where John Cobb’s analysis diverges from Whitehead in two ways:

It would be possible to support this analysis in some detail by citation of passages from Whitehead that point in this direction. However, I resist this temptation. The analysis as a whole is not found in this form in his writings, and it deviates from the apparent implications of some of his statements in at least two ways. First, it rejects the association of God’s aim exclusively with the primordial nature, understood as God’s purely conceptual and unchanging envisagement of eternal objects; this rejection is required if we deny that God’s immutable aim alone adequately explains how God functions concretely for the determination of the events in the world. Second, it interprets the subjective aim of the actual occasion as arising more impartially out of hybrid feelings of aims (propositional feelings whose subjective form involves appetition entertained for the new occasion by its predecessors. In other words, it denies that the initial phase of the subjective aim need be derived exclusively from God. (A Christian Natural Theology)

What Does God Know?

Muhammad Iqbal and the Process Approach

On God's omniscience: God knows all that is actual and all that is possible. God is all-knowing. With regard to the future, the future is knowable as possible, but not as an actuality until it is actual. As soon as it is actual, God knows it with perfect knowledge. The future becomes 'actual' when actualized through the decisions of human beings (and other creatures). As we learn from life experience, God lures or beckons or calls humans to make decisions that are good for themselves and for others; but they may not choose these divinely-preferred possibilities. They may choose evil over good, destruction over solidarity, violence over peace. They are free or self-determining. In the words of the Muslim process-existential philosopher Muhammad Iqbal, "my pleasures, pains, and desires are exclusively mine, forming a part and parcel of my private ego alone. My feelings, hates and loves, judgements and resolutions, are exclusively mine. God Himself cannot feel, judge, and choose for me when various courses of action are open to me." This principle - the principle of open future as a "not-yet - negates the notion that God has preplanned the world and the lives of human beings down to each detail and then created it. Using chess board as an analogy might be illustrative of the closed view which we reject. According to the analogy, God dreamed up the inflexible and essential nature of each piece on the board, i.e., the kings, queens, knights, rooks, bishops, and pawns, and then threw them on the board in a single act. A process understanding of omniscience rejects this notion of predestination (theological fatalism) as it approves of a closed universe in which human entities exists as mere objects. A process understanding of omniscience parallels an existential recognition of freedom. The two go together. In the language of the open theist John Sanders, whose work resonates with process thought, God is "dynamically omniscient."