Pop Music Spirituality

a resource page for students in e-course offered by

Byrd and Jay McDaniel in an influential online platform

for spirituality in the 21st century, Spirituality and Practice

sign up for the two month course, receive two emails a week from Byrd and Jay,

participate in learning circles, and be in conversation with other students

about the intersection of pop music and spirituality, by clicking here

|

This page offers resources for students in a course taught by Byrd McDaniel and Dr. Jay McDaniel called Pop Music Spirituality. It is for the use of students as they take the course, and also for anyone who happens upon the page and wants to think about the intersection of theology and popular music. The sections of the page are numbered so that you can browse with ease and find what interests you. Please use freely.

|

1. "I Want your Voice in My Ear"

2. The Personal Side: A Musically Interested Family

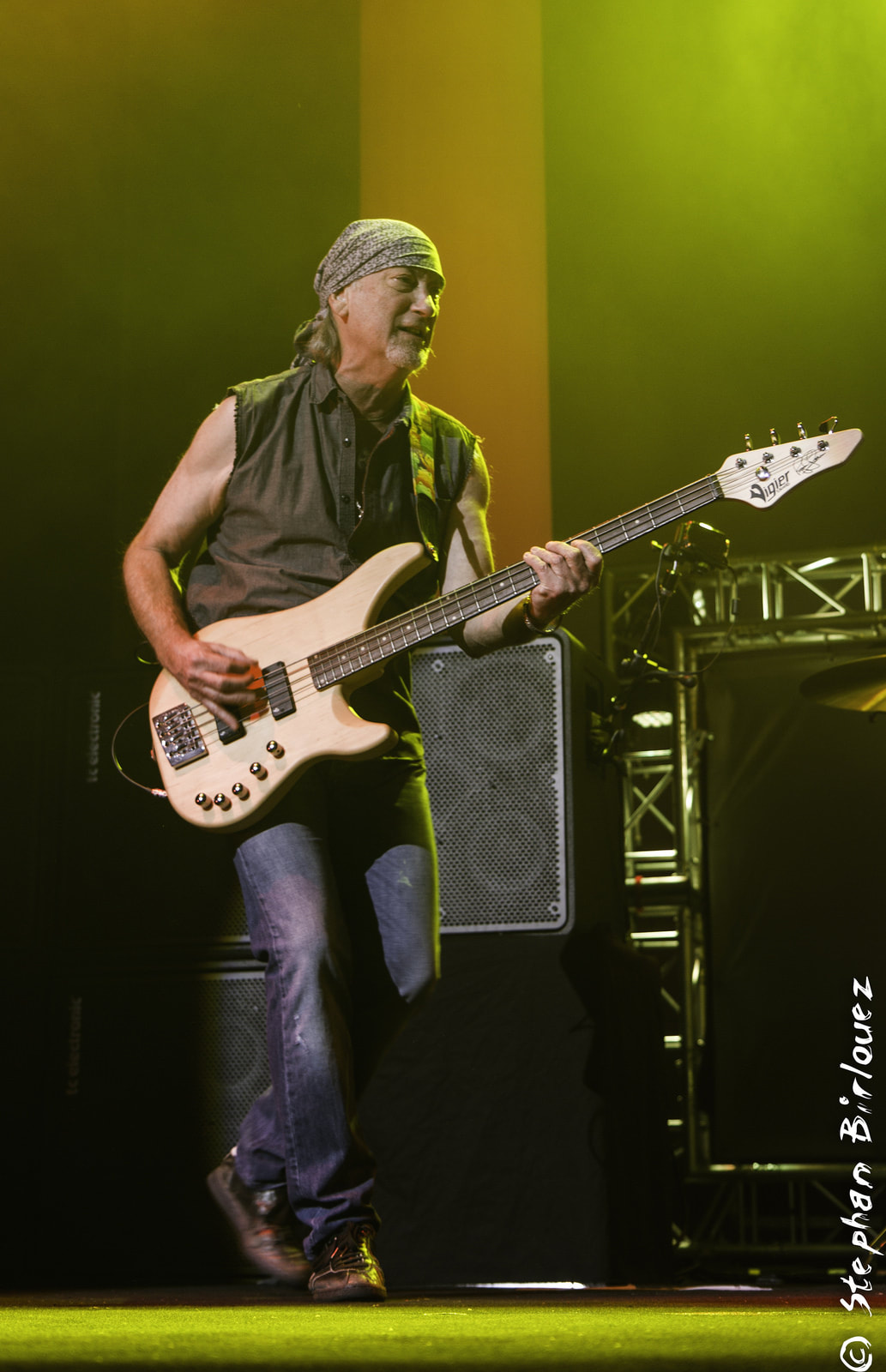

https://byrdmcdaniel.com/

https://byrdmcdaniel.com/

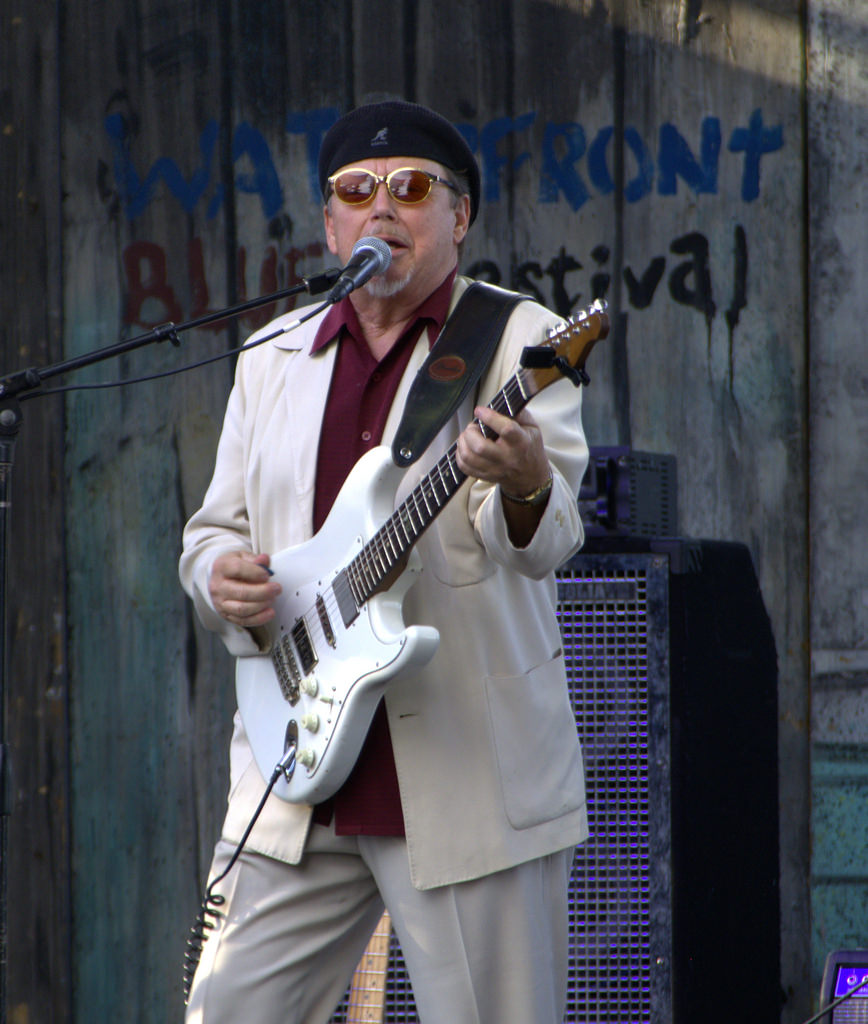

I am not the person in the photo. That's my son, Byrd McDaniel. Most of what I know about popular music studies comes from him. He is in a PhD program at Brown University in the all-but-dissertation stage. Byrd's special focus is on the role of popular music in contemporary culture.

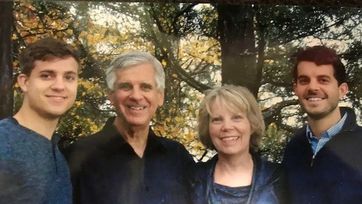

Byrd and I love music of all kinds. He played French Horn in high school and plays guitar now. I introduced him to the music of my youth (Elvis, the Beatles, Bob Dylan, etc.) and he, along with his brother Matthew, kept me abreast of much that's come after. Both Byrd and Matthew grew up with and around hip-hop, and Matthew developed a special affinity for alternative country music. The three of us talk about music all the time. Often my wife Kathy joins in. She loves the music of Broadway plays and the pop music of the seventies. She also supports and promotes a band I'm in that plays at local senior citizen centers. You can learn a little about my band in Musicking for a Better World. We are a music-interested family.

Byrd and I love music of all kinds. He played French Horn in high school and plays guitar now. I introduced him to the music of my youth (Elvis, the Beatles, Bob Dylan, etc.) and he, along with his brother Matthew, kept me abreast of much that's come after. Both Byrd and Matthew grew up with and around hip-hop, and Matthew developed a special affinity for alternative country music. The three of us talk about music all the time. Often my wife Kathy joins in. She loves the music of Broadway plays and the pop music of the seventies. She also supports and promotes a band I'm in that plays at local senior citizen centers. You can learn a little about my band in Musicking for a Better World. We are a music-interested family.

Matthew, Jay, Kathy, Byrd

Matthew, Jay, Kathy, Byrd

Both of my sons are religious in their ways, as is my wife Kathy. Some of us draw from church affiliations and some do not. Kathy and I have a special affinity for the spiritual orientation of Pope Francis in Laudato Si. Not the gender assumptions, but most everything else: service to the poor, a sense of beauty, a love of life, a concern for the earth, a respect for silence, a dialogue with science, a respect for the many world religions, a non-literalistic approach to scripture, a sense of humor, a humility. We are Christians in a Pope Francis way, not a conservative evangelical way. And we both have leanings toward Buddhism. Kathy is a regular recipient of Dalai Lama twitter feeds; I was the English teacher for a Zen master many years ago.

Everyone in my family knows that I am interested in process theology, and all are influenced by it in some ways. They associate it with openness, trust in something more, a sense of connectedness, and compassion. But none are "Whiteheadians," at least the way I am. If I talk too long about it, they get a little bored. It's easier to have longer conversations about music and justice and politics and family relations and life. Their theologies are "daily life" theologies that draw from multiple sources: Christianity, Judaism, Buddhism country music, rock and roll, films, and, of course, personal experience. Everyone I know is in this situation. We are vivid instances of the process idea that, moment by moment, our lives are concrescences of many influences which have varying degrees of influence relative to circumstance. We develop our daily life theologies out of these myriad influences.

A few in the world -- people like me and other philosophical/theological types -- take it has their task to develop "big" theologies that might mean something to larger groups of people. Pope Francis’ Laudato Si is a big theology -- and along with other process theologians I hope that it has a big influence. These "big" theologies have names: Jewish theology, Muslim theology, Christian theology, and sub-names "process Jewish theology" and "process Christian theology" and "process Muslim theology," for example. These "big" theologies play a small role in people's lives, probably much less than their developers wish or imagine. My own versions of "big" theology have been directed to people who are spiritually interested but religiously unaffiliated, and this website has been a primary vehicle. My own view is that the big theologies are, at their best, in service to the daily life theologies and not the other way around.

What has become clear to me is that theologians in general, and process theologians in particular, have not been in conversation with ethnomusicology. To be sure, some theologians (mostly Christian) have been developing theologies from popular music. And to my mind they are right to do so. In so many ways popular music and film have become, for many in the world, a primary source of inspiration, functioning as sacred texts. But few if any of them have been process theologians. And most theologians who develop theologies from popular music do so without reference to work in ethnomusicology -- and the other way around! Byrd and I are among the few theoreticians I know who are interested in, and engaged with, the intersection of popular music theology and ethnomusicology. This course is part of that journey. He gives me the ethnomusicology, I offer the Whitehead.

Everyone in my family knows that I am interested in process theology, and all are influenced by it in some ways. They associate it with openness, trust in something more, a sense of connectedness, and compassion. But none are "Whiteheadians," at least the way I am. If I talk too long about it, they get a little bored. It's easier to have longer conversations about music and justice and politics and family relations and life. Their theologies are "daily life" theologies that draw from multiple sources: Christianity, Judaism, Buddhism country music, rock and roll, films, and, of course, personal experience. Everyone I know is in this situation. We are vivid instances of the process idea that, moment by moment, our lives are concrescences of many influences which have varying degrees of influence relative to circumstance. We develop our daily life theologies out of these myriad influences.

A few in the world -- people like me and other philosophical/theological types -- take it has their task to develop "big" theologies that might mean something to larger groups of people. Pope Francis’ Laudato Si is a big theology -- and along with other process theologians I hope that it has a big influence. These "big" theologies have names: Jewish theology, Muslim theology, Christian theology, and sub-names "process Jewish theology" and "process Christian theology" and "process Muslim theology," for example. These "big" theologies play a small role in people's lives, probably much less than their developers wish or imagine. My own versions of "big" theology have been directed to people who are spiritually interested but religiously unaffiliated, and this website has been a primary vehicle. My own view is that the big theologies are, at their best, in service to the daily life theologies and not the other way around.

What has become clear to me is that theologians in general, and process theologians in particular, have not been in conversation with ethnomusicology. To be sure, some theologians (mostly Christian) have been developing theologies from popular music. And to my mind they are right to do so. In so many ways popular music and film have become, for many in the world, a primary source of inspiration, functioning as sacred texts. But few if any of them have been process theologians. And most theologians who develop theologies from popular music do so without reference to work in ethnomusicology -- and the other way around! Byrd and I are among the few theoreticians I know who are interested in, and engaged with, the intersection of popular music theology and ethnomusicology. This course is part of that journey. He gives me the ethnomusicology, I offer the Whitehead.

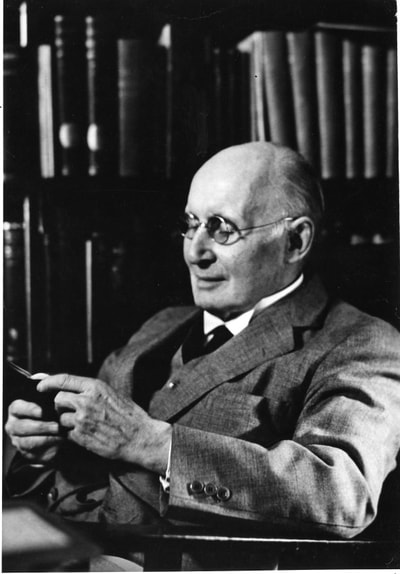

3. What Whitehead Adds

What Whitehead offers is a cosmology that can help us understand and appreciate the role that popular music plays in life, linking it with a sense of the horizontal sacred, the vertical sacred, or both.

From Whitehead's perspective as developed in Process and Reality, the aim of life, moment by moment, is satisfying intensity in an interconnected world. If for some reason you would like an introduction to this book, I recommend my own video series; Reading Process and Reality. You might especially appreciate video #12, which illustrates Whitehead's notion of propositions (lures for feeling) with reference to John Coltrane.

In any case, Whitehead's proposal that all actualities of any sort, in any imaginable universe, aim at satisfying intensity forms a backdrop for this course. From a Whiteheadian perspective the aim of all popular music -- whether performed or consumed or danced to -- likewise has the aim of satisfying intensity. Indeed, so I suggest, when performing it and when enjoying it, we are aiming at satisfying intensity in at least eight forms: creativity, romantic exploration, transgressive exploration, erotic power, immersion in the numinous, storytelling, and communitas (collective joy).

The aim at satisfying intensity is not always life-enhancing. Popular music can be (and has been) used to torture people, send people into battle, and lead people to treat others as mere objects. It is not always conducive to a psychologically healthy life or to what Byrd McDaniel calls a "just and joyful society."

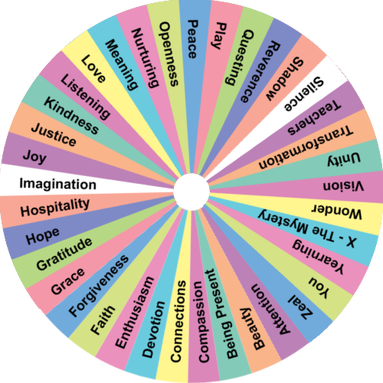

Some, influenced by the Frankfurt School of Culture Studies, believe that, under the sway of consumer culture and the music industry (the art industrial complex), much popular music is shallow, soporific, and anesthetizing. It keeps people from exercising their power of self-determination and critiquing society. Others, influenced by the Birmingham School of Culture Studies, emphasize the agency of the consumer of music, arguing that the content and effects of popular music in human life depends on the particularities of consumers, regardless of the intentions of the music industry. In our course we want to be open to both points of view, but our primary interest is in the consumers and partakers, not the intentions of the music industry. In the same spirit that contemporary interfaith studies encourage people to develop what Eboo Patel calls an "appreciative knowledge" of other traditions, we will be interested in developing an "appreciative knowledge" of the music other people like, even if it happens not to be our music. Thus we will be looking for ways that performing, listening to, and dancing to popular music are contexts for helping people enjoy one or several of the "spiritual moods" highlighted by the Brussats. One such mood is justice, but another is play; one is compassion, and another is self-empowerment (you).. All are good for people.

For those inspired by Whitehead's understanding of God, God is the indwelling lure toward satisfying intensity and also the eternal Companion who shares in the feelings of all living beings. In our course we speak of God understood this way as the vertical sacred. For those inspired by Whitehead's understanding of a cosmos of mutual becoming, God or no God, popular music is one among many ways that people participate in the cosmos of mutual becoming. They are interested in the horizontal sacred. A unique feature of Whitehead's thought is that it finds the vertical in the horizontal and the horizontal in the vertical: intimacy is in transcendence and transcendence is in intimacy. Nevertheless, many people focus on the horizontal not the vertical. Thus, in considering connections between popular music and process theology, we are open to theistic and non-theistic approaches.

From Whitehead's perspective as developed in Process and Reality, the aim of life, moment by moment, is satisfying intensity in an interconnected world. If for some reason you would like an introduction to this book, I recommend my own video series; Reading Process and Reality. You might especially appreciate video #12, which illustrates Whitehead's notion of propositions (lures for feeling) with reference to John Coltrane.

In any case, Whitehead's proposal that all actualities of any sort, in any imaginable universe, aim at satisfying intensity forms a backdrop for this course. From a Whiteheadian perspective the aim of all popular music -- whether performed or consumed or danced to -- likewise has the aim of satisfying intensity. Indeed, so I suggest, when performing it and when enjoying it, we are aiming at satisfying intensity in at least eight forms: creativity, romantic exploration, transgressive exploration, erotic power, immersion in the numinous, storytelling, and communitas (collective joy).

The aim at satisfying intensity is not always life-enhancing. Popular music can be (and has been) used to torture people, send people into battle, and lead people to treat others as mere objects. It is not always conducive to a psychologically healthy life or to what Byrd McDaniel calls a "just and joyful society."

Some, influenced by the Frankfurt School of Culture Studies, believe that, under the sway of consumer culture and the music industry (the art industrial complex), much popular music is shallow, soporific, and anesthetizing. It keeps people from exercising their power of self-determination and critiquing society. Others, influenced by the Birmingham School of Culture Studies, emphasize the agency of the consumer of music, arguing that the content and effects of popular music in human life depends on the particularities of consumers, regardless of the intentions of the music industry. In our course we want to be open to both points of view, but our primary interest is in the consumers and partakers, not the intentions of the music industry. In the same spirit that contemporary interfaith studies encourage people to develop what Eboo Patel calls an "appreciative knowledge" of other traditions, we will be interested in developing an "appreciative knowledge" of the music other people like, even if it happens not to be our music. Thus we will be looking for ways that performing, listening to, and dancing to popular music are contexts for helping people enjoy one or several of the "spiritual moods" highlighted by the Brussats. One such mood is justice, but another is play; one is compassion, and another is self-empowerment (you).. All are good for people.

For those inspired by Whitehead's understanding of God, God is the indwelling lure toward satisfying intensity and also the eternal Companion who shares in the feelings of all living beings. In our course we speak of God understood this way as the vertical sacred. For those inspired by Whitehead's understanding of a cosmos of mutual becoming, God or no God, popular music is one among many ways that people participate in the cosmos of mutual becoming. They are interested in the horizontal sacred. A unique feature of Whitehead's thought is that it finds the vertical in the horizontal and the horizontal in the vertical: intimacy is in transcendence and transcendence is in intimacy. Nevertheless, many people focus on the horizontal not the vertical. Thus, in considering connections between popular music and process theology, we are open to theistic and non-theistic approaches.

4. The History of Popular Music in America (Ann Powers)

|

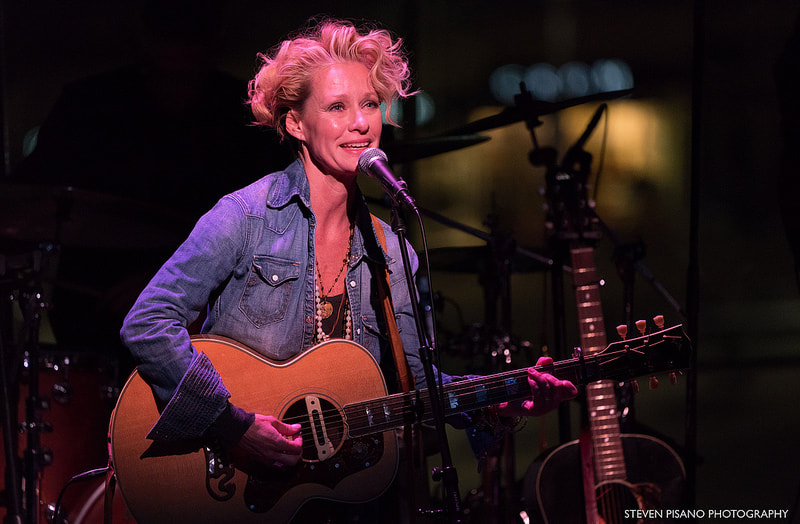

As you take this course, you will quickly realize (as do we all) that popular music includes many, many genres and has a long history in the United States. For me, one of the most important sources in understanding the history is Ann Powers "Good Booty: Love and Sex, Black and White, Body and Soul in American Popular Music." Here is how NPR describes her book:

"The critic and correspondent for NPR Music explores the history of American popular music as an erotic art form, from 19th-century New Orleans and the Jazz Age in New York, to the screaming teens that welcomed The Beatles and modern day web-based performers. 75,000 first printing." And below you might enjoy a short, five-minute interview with her about her book.

As I was thinking about this course, I brought Ann Powers to Hendrix College, where I was teaching, and asked her to give a talk on the spiritual side of her life in music.

|

5. Some Textual Sources

|

6. Aims of the Pop Music Spirituality Course Popular music now functions in the lives of many people around the world as a primary source for daily life theology. Daily life theology may or may not be shaped by the more formal theologies offered by various world religions, it is by all means shaped by culture. Along with film, popular is a means by which people form their identities, bond with others, develop their worldviews, explore the spiritual side of their lives, and enjoy momentary touches of transcendence. They do so by listening to music, both live and recorded, while alone and with others. For many in the world popular music is more influential than institutionalized religion. It is a form of what scholars call culture religion. We approach spirituality with help from Frederic and Mary Ann Brussat of Spirituality and Practice, with their identification of 37 moods in spiritual life. Understood in this way, spirituality is the activity of becoming as alive and awake as is possible, given the circumstances of one’s life, and it is available to theists and non-theists alike. Themes for the Eight Weeks, each with two emails 1. Getting Started 2. Empathy 3. Spontaneity 4. Bodily pleasure 5. Grief 6. Traditions 7. Transcendence 8. The Global Context: How Music Moves We consider multiple genres of popular music: rock, pop, hip-hop/rap, rhythm and blues, jazz, country, folk, electronic dance music, and how various genres of popular music can be appreciated and understood with help from process theology, and also how process theology can be deepened and enriched by the sounds and lyrics of the music itself. One aim of the course is to encourage you develop your own daily life theology with help from the Brussat’s Wheel of Spirituality, the eight themes, and the many genres of popular music. Another aim is to help you understand the daily life theologies of others. This understanding is itself a spiritual practice: an act of listening to others and, in the words of Maya Angelou, inviting their voices to “be near to your ear.” For process theologians, the act of understanding others, empathically, is a primary upshot of the general idea that, after all, we live in a universe of mutual becoming, in which, one way or another, all living beings are truly “present in” one another. Music helps us appreciate the differences within the presence and the presence within the differences. 7. A Few Important Thinkers in the Study of Religion and Popular Music

8. Themes to Look For Improvisation and Novelty: The Many Become One and are Increased by One Transgression: Novelty and the Crossing of (Specious) Boundaries Romanticism: Hope for Harmony, personal and social Erotic Power; Reclaiming the unity of mind and body, Whitehead's withness of the body Prophetic Imagination: Availability of fresh possibilities for social critique and hope (Walter Brueggemann) Storytelling; the universe is a communion of subjects, not a collection of objects Experiencing the Numinous (through sound): the power of emotions (subjective forms), appreciation for "the depths" Communitas (ritualized collective Joy in liminal states): Self-Enjoyment in Community with others 9. Assorted Resources in Open Horizon

10. Jay McDaniel (Notes for a Book Not Yet Written) Why study secular popular music? The migration of ‘religious functions’ to secular sphere

11. Twenty Ideas in Process Theology Imagine someone wanted to communicate or present “process theology’ through popular music, what ideas might they try to communicate? 1. Process: The universe is an ongoing process of development and change, never quite the same at any two moments. Every entity in the universe is best understood as a process of becoming that emerges through its interactions with others. The beings of the world are becomings. 2. Interconnectedness: The universe as a whole is a seamless web of interconnected events, none of which can be completely separated from the others. Everything is connected to everything else and contained in everything else. As Buddhists put it, the universe is a network of inter-being. 3. Continuous Creativity: The universe exhibits a continuous creativity on the basis of which new events come into existence over time which did not exist beforehand. This continuous creativity is the ultimate reality of the universe. Everywhere we look we see it. Even God is an expression of Creativity. 4. Nature as Alive: The natural world has value in itself and all living beings are worthy of respect and care. Rocks and trees, hills and rivers are not simply facts in the world; they are also acts of self-realization. The whole of nature is alive with value. We humans dwell within, not apart from, the Ten Thousand Things. We, too, have value. 5. Ethics: Humans find their fulfillment in living in harmony with the earth and compassionately with each other. The ethical life lies in living with respect and care for other people and the larger community of life. Justice is fidelity to the bonds of relationship. A just society is also a free and peaceful society. It is creative, compassionate, participatory, ecologically wise, and spiritually satisfying - with no one left behind. 6. Novelty: Humans find their fulfillment in being open to new ideas, insights, and experiences that may have no parallel in the past. Even as we learn from the past, we must be open to the future. God is present in the world, among other ways, through novel possibilities. Human happiness is found, not only in wisdom and compassion, but also in creativity. 7. Thinking and Feeling: The human mind is not limited to reasoning but also includes feeling, intuiting, imagining; all of these activities can work together toward understanding. Even reasoning is a form of feeling: that is, feeling the presence of ideas and responding to them. There are many forms of wisdom: mathematical, spatial, verbal, kinesthetic, empathic, logical, and spiritual. 8. The Self as Person-in-Community: Human beings are not skin-encapsulated egos cut off from the world by the boundaries of the skin, but persons-in-community whose interactions with others are partly definitive of their own internal existence. We depend for our existence on friends, family, and mentors; on food and clothing and shelter; on cultural traditions and the natural world. The communitarians are right: there is no "self" apart from connections with others. The individualists are right, too. Each person is unique, deserving of respect and care. Other animals deserve respect and care, too. 9. Complementary Thinking: The rational life consists not only of identifying facts and appealing to evidence, but taking apparent conflicting ideas and showing how they can be woven into wholes, with each side contributing to the other. In Whitehead’s thought these wholes are called contrasts. To be "reasonable" is to be empirical but also imaginative: exploring new ideas and seeing how they might fit together, complementing one another. 10. Theory and Practice: Theory affects practice and practice affects theory; a dichotomy between the two is false. What people do affects how they think and how they think affects what they do. Learning can occur from body to mind: that is, by doing things; and not simply from mind to body. 11. The Primacy of Persuasion over Coercion: There are two kinds of power – coercive power and persuasive power – and the latter is to be preferred over the former. Coercive power is the power of force and violence; persuasive power is the power of invitation and moral example. 12. Relational Power: This is the power that is experienced when people dwell in mutually enhancing relations, such that both are “empowered” through their relations with one another. In international relations, this would be the kind of empowerment that occurs when governments enter into trade relations that are mutually beneficial and serve the wider society; in parenting, this would be the power that parents and children enjoy when, even amid a hierarchical relationship, there is respect on both sides and the relationship strengthens parents and children. 13. The Primacy of Particularity: There is a difference between abstract ideas that are abstracted from concrete events in the world, and the events themselves. The fallacy of misplaced concreteness lies in confusing the abstractions with the concrete events and focusing more on the abstract than the particular. 14. Experience in the Mode of Causal Efficacy: Human experience is not restricted to acting on things or actively interpreting a passive world. It begins by a conscious and unconscious receiving of events into life and being causally affected or influenced by what is received. This occurs through the mediation of the body but can also occur through a reception of the moods and feelings of other people (and animals). 15. Concern for the Vulnerable: Humans are gathered together in a web of felt connections, such that they share in one another’s sufferings and are responsible to one another. Humans can share feelings and be affected by one another’s feelings in a spirit of mutual sympathy. The measure of a society does not lie in questions of appearance, affluence, and marketable achievement, but in how it treats those whom Jesus called "the least of these" -- the neglected, the powerless, the marginalized, the otherwise forgotten. 16. Evil: “Evil” is a name for debilitating suffering from which humans and other living beings suffer, and also for the missed potential from which they suffer. Evil is powerful and real; it is not merely the absence of good. “Harm” is a name for activities, undertaken by human beings, which inflict such suffering on others and themselves, and which cut off their potential. Evil can be structural as well as personal. Systems -- not simply people -- can be conduits for harm. 17. Education as a Lifelong Process: Human life is itself a journey from birth (and perhaps before) to death (and perhaps after) and the journey is itself a process of character development over time. Formal education in the classroom is a context to facilitate the process, but the process continues throughout a lifetime. Education requires romance, precision, and generalization. Learning is best when people want to learn. 18. Religion and Science: Religion and Science are both human activities, evolving over time, which can be attuned to the depths of reality. Science focuses on forms of energy which are subject to replicable experiments and which can be rendered into mathematical terms; religion begins with awe at the beauty of the universe, awakens to the interconnections of things, and helps people discover the norms which are part of the very make-up of the universe itself. 19. God: The universe unfolds within a larger life – a love supreme – who is continuously present within each actuality as a lure toward wholeness relevant to the situation at hand. In human life we experience this reality as an inner calling toward wisdom, compassion, and creativity. Whenever we see these three realities in human life we see the presence of this love, thus named or not. This love is the Soul of the universe and we are small but included in its life not unlike the way in which embryos dwell within a womb, or fish swim within an ocean, or stars travel throught the sky. This Soul can be addressed in many ways, and one of the most important words for addressing the Soul is "God." The stars and galaxies are the body of God and any forms of life which exist on other planets are enfolded in the life of God, as is life on earth. God is a circle whose center is everywhere and circumference nowhere. As God beckons human beings toward wisdom, compassion, and creativity, God does not know the outcome of the beckoning in advance, because the future does not exist to be known. But God is steadfast in love; a friend to the friendless; and a source of inner peace. God can be conceived as "father" or "mother" or "lover" or "friend." God is love. 20. Faith: Faith is not intellectual assent to creeds or doctrines but rather trust in divine love. To trust in love is to trust in the availability of fresh possibilities relative to each situation; to trust that love is ultimately more powerful than violence; to trust that even the galaxies and planets are drawn by a loving presence; and to trust that, no matter what happens, all things are somehow gathered into a wider beauty. This beauty is the Adventure of the Universe as One. |