Process Theology and

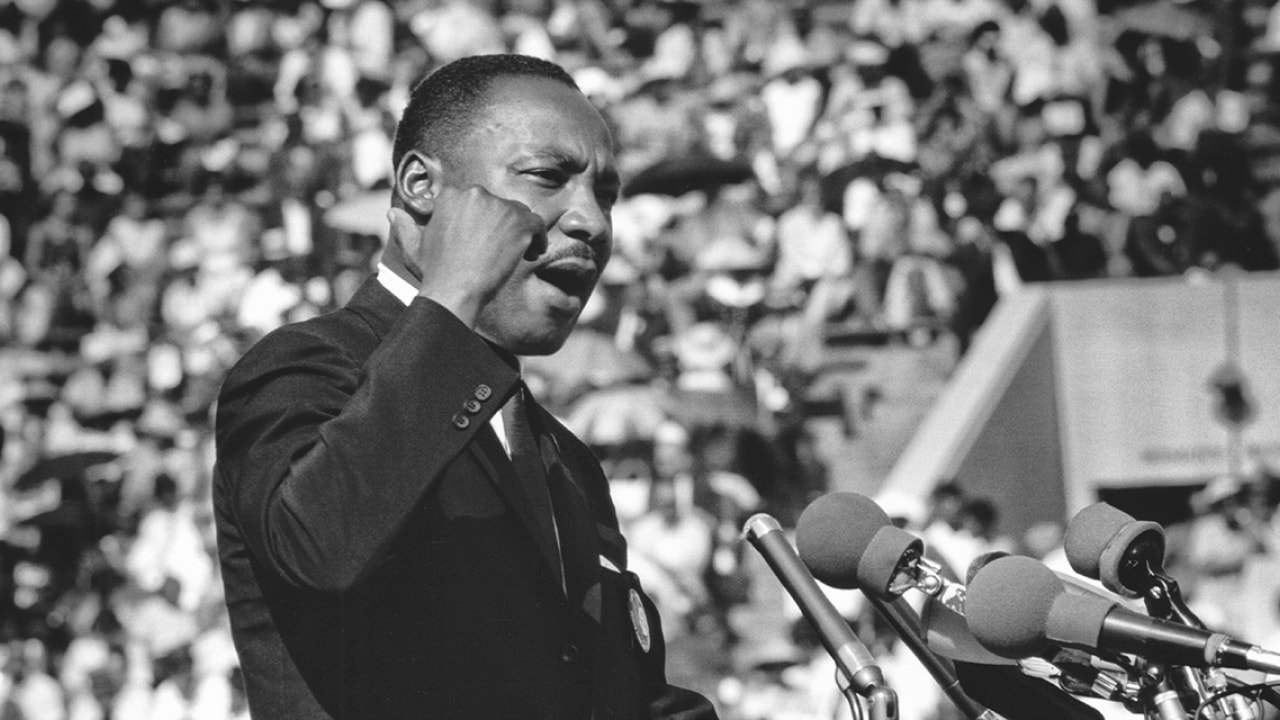

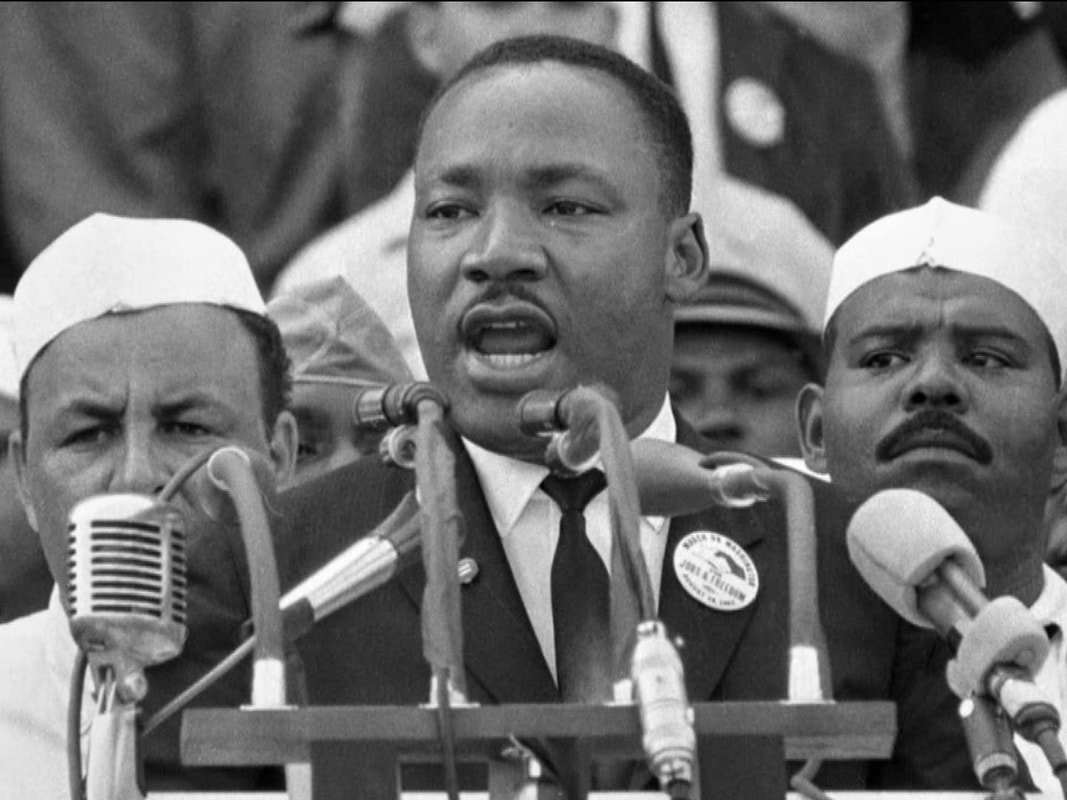

Martin Luther King, Jr.

Seven Similarities

Martin Luther King, Jr. was not a process theologian in any formal way. Still, his approach to religion and life resembles that of many process theologians in seven respects:

King would disagree with process theologians in their rejection of creatio ex nihilo, emphasizing instead that God is self-limiting rather than limited by the power of the world. But he was not very interested in debates on such matters, having his mind and heart focussed on what he took to be more important matters: e.g. social justice.

- King had an appreciation of liberal theology as he learned it at Crozer Theology School, preferring it to Barth's biblicist approach. In this he resembles process thinkers with their apprecation of natural theology.

- King wrote his dissertation on Tillich and Weiman, critiquing both for not understanding for not affirming God is a person with consciousness and intentions, thus preferring the liberal theology of Boston Personalism. In this he resembles many process thinkers with their emphasis on a personal God who "feels the feelings" of all living beings and responds with love by offering fresh possibilities for wisdom, compassion and creativity.

- King believed in God and evolution, understanding God as a source of novelty in the universe. In this he resembles process theologians with their appreciation of a God who works cosmically and not just humanly.

- King believed in non-violence. In this he is close to process theologians with their emphasis on persuasion not coercion.

- King recognized that the non-violent life includes how people think and feel as well as how they act. In this he resembles Gandhi and process theologians, who likewise recognize the important of subjectivity in human life (emotions, intentions, subjective aims, subjective forms) and who, as committed to persuasation not coercion, recognize that the life of relational love has an inner dimension.

- King believed that the religious life rightly requires helping build communities that are creative, compassionate, participatory, egalitarian, and spiritually satisfying with no one left behind. In this he shares the hope of process theologians, who likewise seek such communities and add that are part of what is involved in "ecological civlizations." King also believed, as do many process theologians, that the realization of such community requires a fundamental re-thinking of economics and a critique of consumption obsessed, greed-driven, corporation-controlled capitalism.

- King was an ecumenist, interested in inter-faith harmony. In this he resembles process theologians who, whether Christian or Jewish or Muslim or Hindu or Buddhist, are likewise drawn to interfaith cooperation and mutual transformation through dialogue.

King would disagree with process theologians in their rejection of creatio ex nihilo, emphasizing instead that God is self-limiting rather than limited by the power of the world. But he was not very interested in debates on such matters, having his mind and heart focussed on what he took to be more important matters: e.g. social justice.

|

“I am many things to many people; Civil Rights leader, agitator, trouble-maker, and orator, but in the quiet resources of my heart, I am fundamentally a clergyman, a Baptist preacher,” he said. “This is my being and my heritage. … The Church is my life and I have given my life to the Church.” (Martin Luther King, Jr., 1965)

|

|

|

|

Martin Luther King, Jr.'s Early Theology

King's Understanding of God and Evolution |

King's Appreciation of Liberal Theology About King's Dissertation on Tillich and Wieman |

Boston Personalism and Whiteheadian Theology

John B. Cobb, Jr. for Phillip Fletcher

If, in my quest to see whether, or to what extent, what is now known can support, or even allow, the faith of my youth, I had gone to Boston University instead of the University of Chicago, I would no doubt have become a Personalist. When I encountered Personalist theology in my reading, I found it, in general, quite satisfying. Indeed, it was much more fully and systematically developed than anything that the Divinity School of Chicago offered. While at the Divinity School I imagined teaching philosophy of religion to college students, and I remember thinking that I would use a book of Brightman as the text.

If I had not studied Whitehead, I would probably not have asked the questions to which Personalist philosophy’s answers were less developed than Hartshorne’s or, especially, Whitehead’s thought. Probably, when I did begin to encounter the questions not as adequately dealt with in Personalist philosophy, I would have felt that the needed development was possible without giving up the philosophy overall.

However, I now consider myself fortunate to have come to Personalism after having encountered Whitehead rather than the other way. Personalism developed in the context of German Idealism. That developed from Immanuel Kant’s acceptance of the limitations Hume had shown in British empiricism. The key point was that Hume showed that when we examine very carefully what we actually see, we cannot discover any causal relation. It seems, then that the causal relations, so important to the sciences, must be imposed on the data by habitual expectations generated by repeated occurrences of sequences.

Kant carried this further and, noting the limitations of what we actually see in relation to our scientific understanding of the world, he attributed the construction of the scientific world to the human mind. The whole German Idealist tradition adopted this view, which gave a decisive role to the constructive activity of the mind. Personalism developed as one expression of this tradition.

As a Whiteheadian, when confronted with the acute problems resulting from the way we had treated nature, I was embarrassed by how little attention I had given theologically to the natural world. But change was easy. The philosophy I was using provided me with all I needed in order to change. With German idealism, the situation was different. In my view Kant’s thought still blocks many people from treating the problems in nature as just as objective, just as real, as problems in human relations. Breaking out of anthropocentrism requires breaking out of Kantian idealism.

Correcting the mistakes of David Hume is far from easy, but it has been done for us, quite intentionally and successfully by Whitehead. Much of the strength of Personalism can be incorporated into a Whiteheadian system, but I do not think that a fully realistic view of the natural world can be incorporated into Personalism without fundamental philosophical changes.

As a problem of German Idealism’s understanding of nature, I have noted only its difficulty in responding well to the ecological crisis. But the problem is broader. Whitehead’s philosophy can be useful in science as well as in theology. Personalism can show how theology and science can coexist without conflict, but I do not see how it can assist science to develop. Quantum physicists do often find Whitehead useful. I think that Whitehead can also help us to understand the continuity and discontinuity between the animate and the inanimate as well as the whole process of emergence that we call evolution.

Most of what I have said above about the advantages of Whitehead is not particularly controversial. I will add that, also, specifically in the doctrine of God, I prefer Whitehead. I appreciate Personalism’s affirmation of God as personal, but I think the understanding of persons, when they are viewed in contrast to their natural contexts, is not adequate. Being personal then means too exclusively, like the minds or selves of human beings. Since Personalism does not have as clear a doctrine of “internal relations” as Whitehead, being like a human mind meant being primarily external to other minds. The relation to God is certainly I/thou rather than I/it, but the Pauline understanding of how God is in us and we are in God is hard to envision.

For Whitehead, every entity or event is to some extent inclusive of what has already occurred. Human beings include and reenact much more than do amoeba. God’s difference is the fullness of inclusion. Alongside God’s inclusion of us is the assurance that God is included in every experience. Whitehead’s God is a necessary participant in the coming to be of every creaturely event, but God is not the sufficient cause of any creaturely event. The occurrence of evil and injustice in the world is, of course, an enormous problem, but it is not an intellectual problem, and therefore not an inescapable existential problem. The fact that God works creatively in everything for good does not lead us to expect that everything will work well or that human beings will respond well to God’s gifts. God is included in us, but so are our personal past and indeed much, much else, that does not support God’s purposes.

Most Protestant theologians chose from the philosophical tradition Schleiermacher or Ritschl rather than Lotze, the leading Personalist. Some renewed Aristotle, who had remained important for Catholics. Many insisted that there was no need for philosophy, one could base one’s beliefs directly on the Bible.

In my opinion the choice by Christians of Personalism, and specifically of the Boston School of Personalism, was, in the second half of the nineteenth century and, down to World War II, an excellent choice, probably the best available. Personalism blended beautifully with the Social Gospel, which was the best available response to the social issues of the industrial era. Knowing that this combination was profoundly relevant to the intellectual and social problems of the time gave those who adopted it, including most Wesleyan leaders, a strength and assurance that we now sorely miss.

However, in a world in which German Idealism is no longer the leader in the philosophical world, and when the problems we face are all bound up with what is happening in the natural world, we cannot solve our problems by returning to that which worked so well in the recent past. I personally wish that the church would seek the same wholeness in the philosophy of Whitehead and the commitment to ecological civilization. It seems to have decided, instead, to largely abandon philosophical and theological commitments. I fear that this is a fatal mistake.

-- John Cobb

John B. Cobb, Jr. for Phillip Fletcher

If, in my quest to see whether, or to what extent, what is now known can support, or even allow, the faith of my youth, I had gone to Boston University instead of the University of Chicago, I would no doubt have become a Personalist. When I encountered Personalist theology in my reading, I found it, in general, quite satisfying. Indeed, it was much more fully and systematically developed than anything that the Divinity School of Chicago offered. While at the Divinity School I imagined teaching philosophy of religion to college students, and I remember thinking that I would use a book of Brightman as the text.

If I had not studied Whitehead, I would probably not have asked the questions to which Personalist philosophy’s answers were less developed than Hartshorne’s or, especially, Whitehead’s thought. Probably, when I did begin to encounter the questions not as adequately dealt with in Personalist philosophy, I would have felt that the needed development was possible without giving up the philosophy overall.

However, I now consider myself fortunate to have come to Personalism after having encountered Whitehead rather than the other way. Personalism developed in the context of German Idealism. That developed from Immanuel Kant’s acceptance of the limitations Hume had shown in British empiricism. The key point was that Hume showed that when we examine very carefully what we actually see, we cannot discover any causal relation. It seems, then that the causal relations, so important to the sciences, must be imposed on the data by habitual expectations generated by repeated occurrences of sequences.

Kant carried this further and, noting the limitations of what we actually see in relation to our scientific understanding of the world, he attributed the construction of the scientific world to the human mind. The whole German Idealist tradition adopted this view, which gave a decisive role to the constructive activity of the mind. Personalism developed as one expression of this tradition.

As a Whiteheadian, when confronted with the acute problems resulting from the way we had treated nature, I was embarrassed by how little attention I had given theologically to the natural world. But change was easy. The philosophy I was using provided me with all I needed in order to change. With German idealism, the situation was different. In my view Kant’s thought still blocks many people from treating the problems in nature as just as objective, just as real, as problems in human relations. Breaking out of anthropocentrism requires breaking out of Kantian idealism.

Correcting the mistakes of David Hume is far from easy, but it has been done for us, quite intentionally and successfully by Whitehead. Much of the strength of Personalism can be incorporated into a Whiteheadian system, but I do not think that a fully realistic view of the natural world can be incorporated into Personalism without fundamental philosophical changes.

As a problem of German Idealism’s understanding of nature, I have noted only its difficulty in responding well to the ecological crisis. But the problem is broader. Whitehead’s philosophy can be useful in science as well as in theology. Personalism can show how theology and science can coexist without conflict, but I do not see how it can assist science to develop. Quantum physicists do often find Whitehead useful. I think that Whitehead can also help us to understand the continuity and discontinuity between the animate and the inanimate as well as the whole process of emergence that we call evolution.

Most of what I have said above about the advantages of Whitehead is not particularly controversial. I will add that, also, specifically in the doctrine of God, I prefer Whitehead. I appreciate Personalism’s affirmation of God as personal, but I think the understanding of persons, when they are viewed in contrast to their natural contexts, is not adequate. Being personal then means too exclusively, like the minds or selves of human beings. Since Personalism does not have as clear a doctrine of “internal relations” as Whitehead, being like a human mind meant being primarily external to other minds. The relation to God is certainly I/thou rather than I/it, but the Pauline understanding of how God is in us and we are in God is hard to envision.

For Whitehead, every entity or event is to some extent inclusive of what has already occurred. Human beings include and reenact much more than do amoeba. God’s difference is the fullness of inclusion. Alongside God’s inclusion of us is the assurance that God is included in every experience. Whitehead’s God is a necessary participant in the coming to be of every creaturely event, but God is not the sufficient cause of any creaturely event. The occurrence of evil and injustice in the world is, of course, an enormous problem, but it is not an intellectual problem, and therefore not an inescapable existential problem. The fact that God works creatively in everything for good does not lead us to expect that everything will work well or that human beings will respond well to God’s gifts. God is included in us, but so are our personal past and indeed much, much else, that does not support God’s purposes.

Most Protestant theologians chose from the philosophical tradition Schleiermacher or Ritschl rather than Lotze, the leading Personalist. Some renewed Aristotle, who had remained important for Catholics. Many insisted that there was no need for philosophy, one could base one’s beliefs directly on the Bible.

In my opinion the choice by Christians of Personalism, and specifically of the Boston School of Personalism, was, in the second half of the nineteenth century and, down to World War II, an excellent choice, probably the best available. Personalism blended beautifully with the Social Gospel, which was the best available response to the social issues of the industrial era. Knowing that this combination was profoundly relevant to the intellectual and social problems of the time gave those who adopted it, including most Wesleyan leaders, a strength and assurance that we now sorely miss.

However, in a world in which German Idealism is no longer the leader in the philosophical world, and when the problems we face are all bound up with what is happening in the natural world, we cannot solve our problems by returning to that which worked so well in the recent past. I personally wish that the church would seek the same wholeness in the philosophy of Whitehead and the commitment to ecological civilization. It seems to have decided, instead, to largely abandon philosophical and theological commitments. I fear that this is a fatal mistake.

-- John Cobb