- Home

- Process Worldview

- Community

- Art and Music

- Whitehead and Process Thinking

- Podcasts

- Spirituality

- Ecological Civilization

- Education

- Contact

- Social Justice

- Science

- Animals

- Sacred Poems

- Whitehead Videos

- Index of All Titles

- Practicing Process Thought

- Process Spirituality: A Spiritual Alphabet

- Recent Posts

Open and Relational Theology

|

Imagine that God revealed in Jesus (but not in him alone) is not a policeman in the sky or a king on a throne, but rather an embracing unity in whose heart the universe lives and moves and has its being. God's very nature is compassion. Like a loving parent, God "feels the feelings" of all living beings with tender care and then responds to what is felt with possibilities for healing and wholeness.

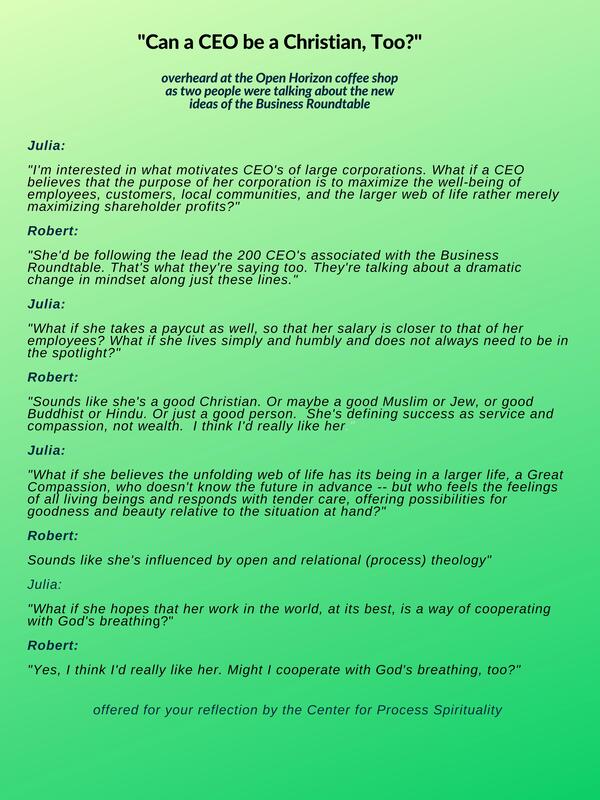

Consider that this God is not all-powerful in a traditional sense; there are plenty of things that happen in the world that are painful to God. Nor is the future known in advance by this God. God knows all lthat is possible, but not all that is actual until it is actual, and the future is not yet actual, But this God is indeed all-loving and all-faithful. This is how open and relational people of faith -- whether Christian or Jewish, Muslim or Buddhist -- envision the very heart of the universe. Deep down, one way or another, they trust in love. Many among them believe that what society most needs today is a building of what many call "ecological civilizations." Their desire is to help build local communities that are creative, compassionate, multi-cultural, multi-religious, humane to animals, and good for the earth, with no one left behind. Can CEO's help? The question is important because small but deeply influential portion of these people of faith are the CEO's of corporations. They understandably ask themselves: "And how might I envision the purpose of the corporation I oversee and serve?" For fifty years or so, their answer was simple: "The purpose of a corporation is to maximize profits for shareholders, pure and simple. Other benefits -- to employees, customers, communiy, and society writ-large -- are important but secondary to this primary commitment. The idea went by the name shareholder primacy. Recently the Business Roundable, a group of chief executive officers of major U.S. corporations formed to promote pro-business public policy, propose that maximizing shareholder profits cannot and should not be the primary goal of corporations. The primary goal should be to enhance the well-being of employees, customers, local communities, and society writ-large. This is good news. |

Beyond Shareholder Supremacy

Nearly 200 chief executives, including the leaders of Apple, Pepsi and Walmart, tried on Monday to redefine the role of business in society — and how companies are perceived by an increasingly skeptical public.

Breaking with decades of long-held corporate orthodoxy, the Business Roundtable issued a statement on “the purpose of a corporation,” arguing that companies should no longer advance only the interests of shareholders. Instead, the group said, they must also invest in their employees, protect the environment and deal fairly and ethically with their suppliers.

-- David Gelles and Daavid Yaffe- Bellany, NY Times, 8/19/2019

For nearly a half-century, corporate America has prioritized, almost maniacally, profits for its shareholders. That single-minded devotion overran nearly every other constituent, pushing aside the interests of customers, employees and communities.

That philosophy was rooted in an idea that has an air of nobility about it. Shareholder democracy was the name given to investors asserting themselves in corporate governance. The idea was that investors would wrest control of companies from entrenched managers, letting the actual owners set their corporate priorities. But what we really got was something else: an era of shareholder primacy.

That may have a chance — a chance — of changing now that 181 chief executives have lent their signatures to a new “Statement on the Purpose of a Corporation” that was published by the Business Roundtable on Monday. The statement from the leaders of companies including JPMorgan Chase, Apple, Amazon and Walmart affirms that the nation’s largest companies have a “fundamental commitment” to all their stakeholders: putting employees, suppliers and communities on a pedestal that once belonged only to shareholders.

The companies’ statement is a significant shift and a welcome one. For years, businesses have resisted calls — including from this column — to rethink their responsibility to society. In response, corporations typically dismissed hot-button topics like income inequality, climate change, gun violence and more as political issues unrelated to them.

-- Andrew Ross Sorkin, NY Times, 8/19/2019

Skepticism

There was no mention at the Roundtable of curbing executive compensation, a lightning-rod topic when the highest-paid 100 chief executives make 245 times the salary of an employee receiving the median pay at their company.

*

For companies to truly make good on their lofty promises, they will need Wall Street to embrace their idealism, too. Until investors start measuring companies by their social impact instead of their quarterly returns, systemic change may prove elusive.

*

Nowhere has the new scrutiny on corporations been more pronounced than on the presidential campaign trail. On Monday, Mr. Sanders said in an interview that the Business Roundtable was “feeling the pressure from working families all over the country.”

“I don’t believe what they’re saying for a moment,” he said. “If they were sincere, they would talk about raising the minimum wage in this country to a living wage, the need for the rich and powerful to pay their fair share of taxes.”

In a statement Monday, Ms. Warren called the announcement “a welcome change” but cautioned that “without real action, it’s meaningless.”

-- David Gelles and Daavid Yaffe- Bellany, NY Times, 8/19/2019